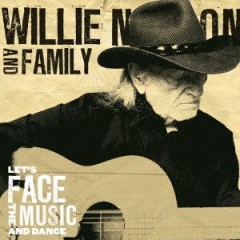

LET’S FACE THE MUSIC AND DANCE

LET’S FACE THE MUSIC AND DANCE

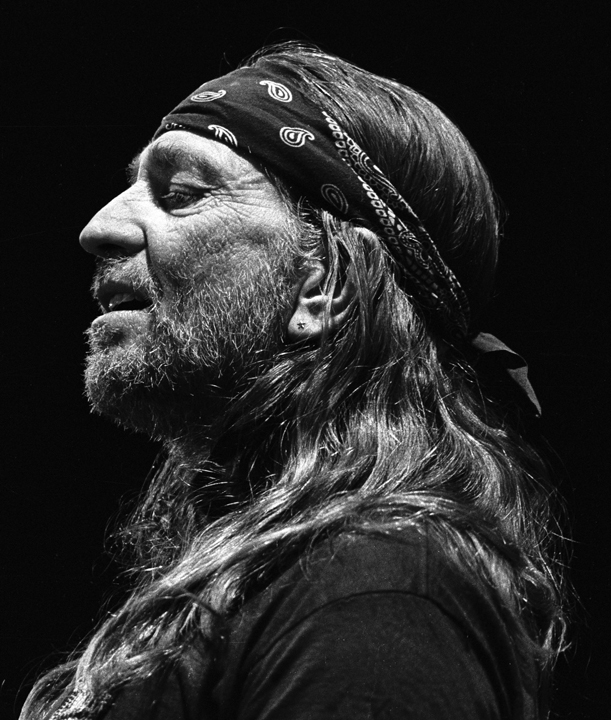

Willie Nelson and Family

Legacy Recordings

“Harold Arlen, Johnny Mercer and Nelson Riddle. A song about a man whose chick has split and he’s hurtin’ very badly. It simply tells the story of a guy who’s left alone because his chick has taken a train or somethin’. And he doesn’t quite know how to handle it; it’s very tough. So after about two weeks of sitting in his house—or his room, I should say—he decides to take a walk and get among us. He falls into a small bar, nobody in there but the bartender and him, and he finds somebody to tell his story to. ‘It’s quarter to three, there’s no one in the place, ‘cept you and me…’”

Thus Frank Sinatra’s spoken prologue to “One for My Baby,” a variation of which became a staple of his latter-day concerts. More to the point of the discussion here, the great Johnny Mercer-Harold Arlen song was a cornerstone of the album the Chairman of the Board cited as his favorite among all his recordings, the 1958 masterpiece Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely. Arranged by Nelson Riddle, conducted by Alex Slatkin (after Riddle took off on tour with Nat King Cole) and featuring the estimable Bill Miller on piano, Only the Lonely included, among other gems, the Sammy Cahn-Jimmy Van Heusen title track (Van Heusen is the most-recorded songwriter in the Sinatra oeuvre); the lovely “Angel Eyes” by the underrated Matt Dennis and Earl Brent; Gordon Jenkins’s “Goodbye”; two Arlen-Mercer gems, “Blues in the Night” and the abovementioned melancholy monument, “One for My Baby”; “Ebb Tide” (Robert Maxwell-Carl Sigman); and Rodgers and Hart’s “Spring Is Here”–a carefully selected program of songs reflecting a wave of moods sweeping inexorably, unceasingly over a forlorn lover. For all many confirmed accounts of Sinatra’s boorish behavior in public, for all his documented intemperate remarks to and about women, he emerged in song as a true romantic (and in his late-career recordings you can hear him clearly remorseful for the insensitivity of his younger days), a man forever giving his heart to another, finding poetry in two souls’ communion, deeply wounded when “his chick has taken a train or somethin’.”

Willie Nelson on Let’s Face the Music and Dance

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ac84Xn1u3Hc

Willie Nelson and Family, the title track from Let’s Face the Music and Dance, written by Irving Berlin

Willie Nelson has been called many things in his life, which now numbers 80 years, but being described as a romantic is a term rarely if ever applied to the red-headed stranger. Then along comes Let’s Face the Music and Dance, with a title song by Irving Berlin (dating from 1936, it was written for the film Follow the Fleet and sung by Fred Astaire and also employed in a memorable dance scene with Astaire and Ginger Rogers; among its many recordings since its introduction are not one but two versions by Sinatra, first in 1961 on his debut Reprise album Ring-a-Ding-Ding, and on his 1981 twilight masterpiece, Trilogy: Past Present Future). From the expressed fatalism the title track offers as the album opener to the closing bitter rebuke of Spade Cooley’s 1945 mega-hit “Shame on You” (#1 country for two months and a charting records for 31 weeks), Let’s Face the Music and Dance charts a bruised but not broken romantic’s tumultuous journey of the heart.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xqPqtpBLS5c

Willie Nelson and Family, ‘Is the Better Part Over,’ from Let’s Face the Music and Dance

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_NHEJ0YQbTM

Willie Nelson and Family, ‘Walking My Baby Back Home,’ from Let’s Face the Music and Dance

Let’s state first that in producer Buddy Cannon Willie found someone who possesses the breadth of musical knowledge necessary to color the atmosphere just so, to insure a continuity of mood and temperament to make the album feel not like a collection of songs but a statement. He’s not credited as an arranger, but his track record suggests he is well capable of offering constructive pointers if he heard something getting away from Willie. Next, Willie’s band is in nothing less than top form here: Billy English distinguishes himself on electric gut string guitar; Paul English is his usual solid, unobtrusive self on snare drum as is newcomer Kevin Smith on upright bass; Bobbie Nelson has moments both lively and touching on the 88s; son Micah Nelson shines on churango and various percussion; and most of all, Willie’s stalwart harmonica man, Mickey Raphael, arguably turns in his best-ever performances here, continuously elevating or enhancing the mood Willie creates, immersing himself so deep into the blue at times as to make his instrumental voice as piercing as Willie’s singing voice.

So far this review has spoken of Frank Sinatra, Buddy Cannon and Willie’s band. Make no mistake: the story of Let’s Face the Music and Dance is Willie Nelson. Yes, his vocals wobble slightly here and there, but on balance he sounds invigorated and engaged throughout. His skill as an interpreter, or as an actor, is striking: on the lone Willie copyright here, “Is the Better Part Over,” from his 1989 album A Horse Called Music (rather overlooked, all in all, even though it rose to #2 on the country chart), he reinvents his own song with a bright but befuddled vocal that invests the lyric with an element of surprise absent from the original, aching version but right on target for what this album needs in order to underscore the protagonist’s near-schizoid worldview. With Raphael blowing evocatively behind him, and his own spare gut-string guitar fills buttressed by the discrete percussion low in the mix, Willie tries to let go even as he knows, deep down, the folly of such an option. Arguably even better, and more unexpected, is the brisk, jazzy shuffle he lends to Carl Perkins’s “Matchbox,” with Billy English and Bobbie Nelson both contributing low-key fire on gut-string electric and piano respectively (along with a hotter, wailing Raphael), but Willie’s easygoing vocal makes the song fit right into the conceptual conceit by sounding like a Falstaff monologue–he probably should have interpolated a line from the immortal Bard and sung “I would you had but the wit” in case any listener misunderstands the intent of a dollop of self-pity and the sense of being uprooted as part and parcel of what Willie’s dealing through the whole trip.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fh7Drd_P1j8

Willie Nelson and Family, ‘You’ll Never Know,’ from Let’s Face the Music and Dance

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dt_e49LJV94

Willie Nelson and Family, ‘Marie (The Dawn is Breaking),’ written by Irving Berlin, from Let’s Face the Music and Dance

The romantic dies hard. Willie swings wildly from exultation to melancholy via such entries as: a spry, optimistic piano-and-vocal remembrance, in the form of the 1930 pop tune “Walking My Baby Back Home,” with delicate solo interchanges by Bobbie Nelson and Mickey Raphael and a curiously ambiguous Willie vocal–more wary than cheery, and a far cry from Nat King Cole’s spry rendering on his 1952 hit single; a tender, saloon-style (not a New York City saloon; more like the Dry Bean in Lonesome Dove, dry, dusty and near-deserted) lover’s distressed confession, “You’ll Never Know” (composed by the great team of Harry Warren and Mack Gordon, it was introduced by Francis Faye in 1943 but is more historically resonant as Sinatra’s first solo single for Columbia, also in 1943); a ruminative take on Frank Loesser’s 1947 beauty, “I Wish I Didn’t Love You So,” as delivered by a man who can’t find it in himself to move on from the wreckage of a love affair gone wrong, a state of mind and heart Raphael evokes with a harmonica solo that moans and cries in abject sorrow. Ultimately Willie winds up in pretty much in the same place he started, albeit going out swinging (musically, that is), with a jaunty “Shame on You,” his “j’accuse” directed at a faithless lover, featuring Willie’s own feisty, Django-influenced guitar solo (the tunestack also includes “Nuages,” Django’s fabled instrumental, which does double duty here in that Willie’s guitar, Raphael’s harmonica and Bobbie’s piano together evoke the heady glory days of gypsy swing, on the one hand, and on the other, given the title’s translation as “Clouds,” the unsettled, shifting moods of the album as a whole). This, in short, is Willie’s torch album, as carefully and deliberately conceived as Sinatra’s great sad beauties of the ‘50s–Only the Lonely, In the Wee Small Hours, No One Cares, Point of No Return–but with a spare, rootsy, southwestern ambience in contrast to the elegant, albeit restrained orchestral embroidery Riddle employed in framing the Chairman’s pensive musings. Willie’s no less pensive than Sinatra here, but the album’s quiet backdrops emphasize the intimate, often painful nature of his confessions, as if you’re the only person in the room when he unburdens himself of these sorrows. It’s very tough, as Sinatra once said, but be glad Willie decided to take a walk and get among us.