Andrew Oldham: ‘As long as that which you hustle is the real thing, you’re in a pretty special place in the world. You are, in fact, at one with the world even if you do not realize it at the time.’

Andrew Oldham’s recently released book Stone Free is, as mentioned here, more a rumination on the art of the hustle than a traditional memoir.

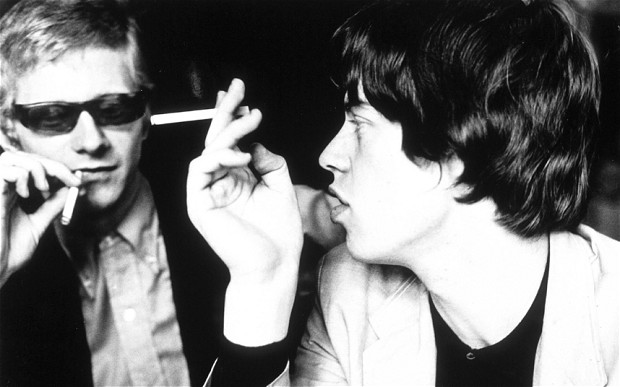

In his earlier volumes Stoned and 2Stoned, the former Stones manager/producer provided a narrative of a career that began a half-century ago when a clueless teenager forsook the usual pursuits of sports and proms to infuse himself into the careers of the holy trinity of the Beatles, the Stones and Bob Dylan before his twentieth birthday.

Now, armed with five decades of street scholarship–his “post-graduate education in double-dealing”–Oldham dissects the moves of such “pimpresarios” as Albert Grossman, Malcolm McLaren and, most important, Allen Klein, among whose hustle-ees were Sam Cooke, the Beatles, the Stones and Oldham himself.

Oldham’s relationship with Allen Klein is the substance of the most complicated and revealing chapter in Stone Free. Armed with extraordinary accounting skills and a relentless pursuit of the hustle, Klein stripped Oldham of his Stones royalties, making him virtually dependent on Klein’s largesse–which was often generous–for his income. (Klein was similarly helpful to the extended family of Sam Cooke after his death.) Rather than playing the victim, Oldham uses the Klein chapter to take responsibility for his own early lack of business acumen.

(Before you buy into the trope of Klein’s empire as all about the money, newly revealed tapes have no less a heroic figure than John Lennon giving Klein credit for what he calls “one of the funniest lines” in Lennon’s scathing anti-Paul song “How Do You Sleep?” from his 1971 solo album Imagine: “The only thing you done was yesterday.”)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LNjTPZW7GCU

John Lennon, ‘How Do You Sleep?’ from his Imagine album. Lennon has said that the line ‘the only thing you done was yesterday’ was supplied by Allen Klein.

A highpoint of Stone Free, edited by Brit-pop expert Ron Ross, is Andrew’s depiction of a meeting with Phil Spector and Seymour Stein in 2008, the year before Spector began serving a 19 years to life sentence for the 2003 murder of Lana Clarkson.

Spector, of course, is the genius behind some of pop music’s greatest singles, including the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby,” the Crystals’ “Then He Kissed Me,” and “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin'” by the Righteous Brothers. He also produced or co-produced such monumental albums as George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass and the above-mentioned Imagine.

Stein is a colorful record biz icon who has played an integral role in the careers of such superstars as the Ramones, the Talking Heads, the Pretenders and Madonna. He’s also amassed a knowledge of popular music that’s beyond encyclopedic. Oldham observes, “If WC Fields had been younger, better looking and not anti-Semitic, he might have been Seymour Stein.”

Stein had first hustled Andrew circa 1964 in New York’s Brill Building, that citadel of songplugging where the Runyonesque inhabitants included bookies disguised as elevator operators. Forty-four years later, Andrew recalls, Phil summoned Andrew to accompany Stein for a meeting at Spector’s mansion in Alhambra, California. The subject: the potential recording career of Phil’s new 28-year-old wife, former Playboy model Rachelle Spector.

In Andrew’s telling–and he’s the first to admit that he’s offering only “the truth of my recall”–Stein politely passes on the deal, and everyone walks away with dignity and shared affection intact.

Just who is hustling whom in this Chinese puzzle is left for the reader to ponder. What’s most interesting–and moving–is how Oldham turns his compassion for Spector into a meditation on the pain of rejection, a universal experience Spector captured so profoundly 45 years ago in “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” which he not only produced but also co-wrote (with Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil). Oldham says, “I know that the pain of rejection is never limited to the snub at hand. It comes in waves, reverberates like a chord with all the other disappointments in a life. Perhaps, finally, this is okay. Rejection is an old friend who can only hurt you if you are foolish enough to let it.”

The Righteous Brothers, ‘You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,’ produced by Phil Spector. In his book Stone Free, Andrew Oldham ‘turns his compassion for Spector into a meditation on rejection.’

For Oldham, an insight machine who writes with a self-deprecating wit that sometimes borders on self-laceration, what matters is the way one conducts a hustle. Reached at his headquarters in Bogota, Columbia, he said, “As long as that which you hustle is the real thing, you’re in a pretty special place in the world. You are, in fact, at one with the world even if you do not realize it at the time.”

Is this declaration a piece of practical advice, a mind-blowing koan or just plain confusing? Andrew writes, you decide.

The title Stone Free is, as Freud would say, overdetermined. It refers to both the author’s hard-fought freedom from over-identification with the Stones and his freedom from the need to get stoned (he’s been sober since the ’90s.) There’s also “Stone Free,” the first song Jimi Hendrix ever wrote, an ode to rock & roll life in the ultra-fast lane, which resonated with Oldham’s experience.

I asked Oldham if he was conscious of an ever deeper, more cosmic connection with another Stone Free: the herbal (drug-free) remedy for kidney and gallstones. (All things must pass, indeed.)

He wasn’t, but ever the hustler, said, “Lawdy, I’d love to do a tie-in! Buy three bottles, get the book free!”

For more by Michael Sigman, click here.

Writer/editor, media consultant, music publisher Michael Sigman is a regular Huffington Post blogger. Follow Michael Sigman on Twitter