It’s said Jeff Barry, songwriting partner and husband of Ellie Greenwich, gave George Morton the nickname “Shadow” for Morton’s ability to suddenly, silently disappear, especially from social settings. In truth he was more like a phrase from Psalm 144: “Man is like a breath; his days are like a fleeting shadow.” For two years in the mid-‘60s, George Morton was a shadow looming over teen pop, a producer’s credit on a Red Bird 45 rpm single, a long-haired, hard drinking Svengali in sunglasses producing youth operettas with a sonic grandeur to rival Spector’s. He can be credited with making legends of three (or four, or five, no one was ever quite sure) tough girls from Queens who were called the Shangri-Las and a cultural icon of precocious 16-year-old Janis Ian, who dared record a groundbreaking, self-composed song about interracial dating that was the talk of a nation in the summer of ’67. He could also share the blame–with the group–for some of ‘60s rock’s most ponderous music in the form of Vanilla Fudge’s egregious, lumbering interpretation of the Supremes’ driving pop-soul hit, “You Keep Me Hanging On” and Iron Butterfly’s 17-minute heavy rock horror show, “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida,” a record Shadow claimed he had little involvement in owing to his inebriation. Never fully enthralled by the music business, he was essentially out of it come the ‘70s, although he popped in during the early part of the decade as producer of the New York Dolls’ Too Much Too Soon, and of recordings by the Ian Hunter-led British band Mott the Hoople, the all-female rock band Isis and singer-songwriter Tom Pacheco.

George Francis “Shadow” Morton died on February 14 in Laguna Beach, CA, following a long battle with cancer.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=snMdXi-e36w

On ‘The Lloyd Thaxton Show,’ the Shangri-Las perform ‘Give Him a Great Big Kiss’ and a cover of the Isley Brothers’ ‘Shout’

Born in Richmond, Virginia, on September 3, 1940, Morton grew up in Brooklyn, NY, and then in the suburb community of Hicksville, Long Island. While in high school he led a doo-wop group called the Marquees and, more importantly, befriended an aspiring songwriter named Ellie Greenwich, whom he had met at a record store. Greenwich, he would learn, had become a successful songwriter with partner (and soon to be husband) Jeff Barry, and was working in Manhattan, in the fabled Brill Building. Morton proceeded to shadow, if you will, Greenwich, popping in unannounced to her and Barry’s office, until one day a jealous Barry asked Morton exactly what he did for a living. To Morton’s answer that he wrote songs, Barry replied with a dare to bring some in.

Out in Queens, Mary Weiss, her older sister Betty and twin sisters Marge and Mary Anne Ganser formed a group and were signed by the Kama Sutra label. One of the Kama Sutra principals was Artie Ripp, who would later help launch Red Bird. The girls took a name–the Shangri-Las–from James Hilton’s book Lost Horizon, and cut an unsuccessful single for Kama Sutra before being discovered by Morton, who was desperate for an entrée into the music business.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6zRHovccHDo

The Shangri-Las, ‘Remember (Walking in the Sand),” produced by Shadow Morton (#5 pop)

At that point, as author Ken Emerson recounted in his history of the Brill Building, Always Magic In the Air (Viking Penguin, 2005): “Now Morton made a demo in a Hicksville recording studio of the Shangri-Las singing a seven-minute soap operetta that he had composed in his head”–Morton could not sing or play an instrument–“it was inspired by the dramatic chords and finger-snapping rhythm of the Modern Jazz Quartet’s ‘Sketch,’ a 1959 John Lewis composition that the group recorded with the Beaux Arts String Quartet. There was nothing artsy about the Shangri-Las nasal ‘quelp,’ as the socioilogist and writer Donna Gaines aptly characterized groups’ ‘combination squeal and yelp,’ the sound of ‘a real teenage girl declaring her love’–in this instance for a boy who had ‘found someone new’ and stranded the singer on a desolate beach with only erotic memories and the cries of gulls to keep her company.”

When Morton, Greenwich, Barry, Ripp and Artie Butler convened in Manhattan’s Mirasound Studio to flesh out the demo, “it became a whole other record,” according to engineer Brooks Arthur as quoted by Emerson, as well as a shorter one suitable for airplay. “The guy with the palette and the colors was Shadow Morton,” Arthur told Emerson, but the finished product was “a cross-pollination” to which everyone contributed.

The Shangri-Las, ‘Leader of the Pack,’ produced by Shadow Morton (#1 pop). This clip is from the popular game show I’ve Got a Secret, and the motorcyclist is Robert Goulet.

Titled “Remember (Walking In the Sand),” the single reached #5 on the pop chart in 1964 and established a prototypical Shangri-Las and Shadow Morton style: volatile characters in a melodramatic plot embellished sonically with spoken passages (sometimes tearful), sound effects and thick, swirling harmonies worthy of an Elmer Bernstein score. The apex of this style came with the Shangri-Las’ next single, “Leader of the Pack,” a signature entry in the teen tragedy sub-genre that had first flowered in 1959 with Mark Dinning’s “Teen Angel” (written by his sister, Jean). Morton always claimed he wrote “Leader” alone (and was backed in that claim by engineer Rod McBrien, who had worked with Morton on the Shangri-Las’ demo), but Barry and Greenwich insisted they added some key ingredients; whatever its lineage, the song did boast the essential teen tragedy element, namely death, and Barry had a track record in that regard, having co-written Ray Peterson’s morbid 1960 hit, “Tell Laura I Love You,” about a boy, Tommy, who tries to impress his girl by entering a car race that he hopes will bring him first place prize money with which to buy her a wedding ring. Instead, his car crashes, burns and leaves a fatally injured Tommy whispering a final, agonized “Tell Laura I love her, and my love for her will never die.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EeofhhabYO0

‘He’s good-bad, but he’s not evil’: The Shangri-Las, ‘Give Him a Great Big Kiss,’ produced by Shadow Morton (#18 pop)

One of the secrets of the Shangri-Las’ approach on “Leader of the Pack” is that it was impossible to tell whether they were being comically or seriously overwrought. In Emerson’s account, Barry was sitting next to Mary Weiss during the recording session (during which a real motorcyle was wheeled into the studio and revved up to create the Leader’s roaring machine), “me on one side of the hanging microphone and she on the other, my side dead. I directed her in it, saying, ‘Look what happened to this guy. Here he is, he loves this girl. And just think about her: she stands there and sees him pull away on his motorcycle.’ I got her all psyched up, and she was crying. When she sang, ‘Look out! Look out! Look out!’ you can hear it. Her performance is a big part of the success of that record. It’s genuine.”

The Shangri-Las, ‘I Can Never Go Home Anymore,’ produced by Shadow Morton

Weiss, describing herself as “a shy person,” told Emerson “the recording studio was the place that you could really release what you’re feeling without everybody looking at you. … I had enough pain in me at the time to pull off anything and get into it and sound believable.”

At #1 on the chart, “Leader of the Pack” was the girls’ second and biggest hit of ’64. To mark the chart topping occasion, Morton bought Barry, who had once been so skeptical of Morton’s talent, a white Honda motorcycle, the first Barry had ever owned. A followup single, “Give Him a Great Big Kiss,” peaked at #18 but was a stomping, upbeat rocker that got the Shangri-Las temporarily out of the doom-and-gloom game (and contained Mary Weiss’s two priceless rejoinders, one to her mates’ observation that she was dating a bad boy–“Mmm, he’s good-bad, but he’s not evil”–the other to the query as to how he dances: a lubricious “Close. Very, very close.”). The next three singles were only minor hits (the highest charting one being 1965’s “Give Us Your Blessings” b/w “Heaven Only Knows,” at #29). But the group came back to familiar territory, both thematically and commercially, with late ‘65’s heart wrenching “I Can Never Go Home Anymore,” a #6 single telling the story of a girl who ran away from home to spite her mother, who had forbidden her romantic interest in a boy, the twist being that the girl’s mother then dies of loneliness and despair. “Don’t do to your mom what I did to mine,” the Shangri-Las counsel at the end, uncharacteristically remorseful for their callousness. Four more singles followed in ’66 and ’67, with “Long Live Our Love” b/w “Sophisticated Boom Boom” being the highest charting entry at #33. The group’s last two singles were recorded for Mercury, where Morton took the group after Red Bird folded in ’66.

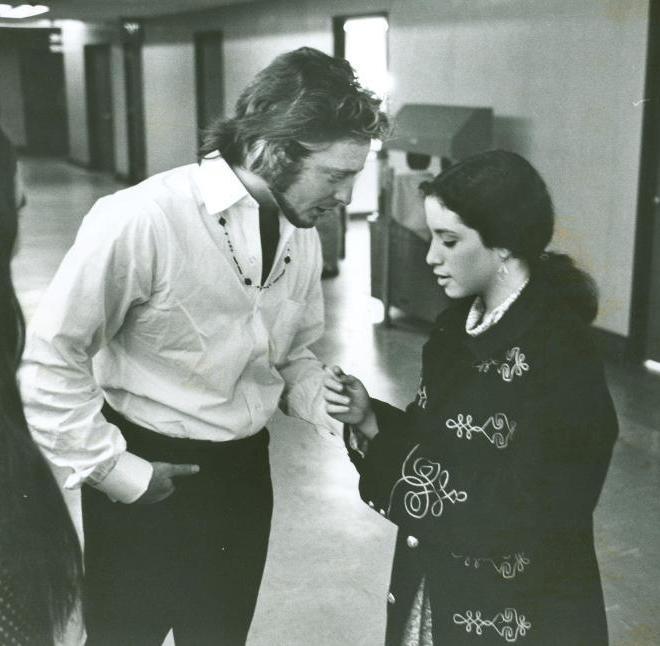

At Mercury Morton mentored young Janis Ian. She had recorded her song of interracial romance, “Society’s Child (Baby I’ve Been Thinking),” for Atlantic, which had paid for the session and then returned the masters to the artist after declining to release the single. Upon teaming up with Ian, Morton guaranteed her a #1 record if she would “change just one word–just change ‘black’ to anything else,” according to Ian’s autobiography, Society’s Child. Ian refused his request and the record failed to top the chart, but it did rise to #14 pop and eventually tallied 600,000 in sales, with its like-titled album logging sales of 350,000. More important, in the summer of “Light My Fire” and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, “Society’s Child” was the topic of national conversation, plenty of it heated over the song’s theme. In 2001 “Society’s Child” was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

An accomplished young Janis Ian on The Smothers Brothers Show performing ‘Society’s Child’

The Shadow Morton-produced single of Janis Ian’s ‘Society’s Child’ (1967)

After Ian, Morton worked with a New York City-based psychedelic band called Haystacks Balboa; the Boston comedy band Gross National Productions; the New York Rock and Roll Ensemble, a rock band using classical instruments and featuring among its members Michael Kamen, who went on to have a distinguished career as a composer and conductor. Then came Vanilla Fudge, Iron Butterfly, Isis, Tom Pacheco and his exit from the music business. After being successfully treated for alcoholism in the ‘80s, Morton fashioned a new career designing golf clubs. He also sued Polygram Records, and lost, over what he considered the unauthorized use of his music in Martin Scorsese’s 1990 film, Goodfellas. His marriage to Lois Berman ended in divorce. He is survived by three daughters, three grandchildren and a sister.