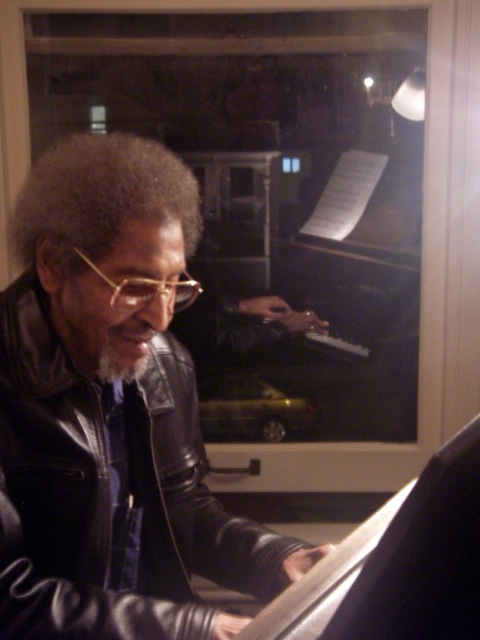

Bobby Sharp at the piano on his 84th birthday. (Photo: Kriss Mikkelson, posted at the website of vocalist Clara Bellino, www.clarabellino.com)

In 1961 Bobby Sharp was out of it, addicted to drugs and languishing in his parents’ apartment in Harlem’s once-exclusive Sugar Hill neighborhood. As mom and dad Sharp watched TV in the next room, Bobby gathered himself, wrote a song and sold it the next day for $50, enough to buy a new supply of drugs.

“I was strung out,” Sharp told San Francisco Chronicle senior pop music critic Joel Selvin. “I needed to write something catchy.”

Sharp, 88, of Alameda, California, passed away on Monday, January 28. His passing marked the end of a life filled with generosity toward friends, colorful storytelling about mid-century times in Los Angeles, New York, and California, and a long songwriting career highlighted by that 1961 song, “Unchain My Heart,” which became one of Ray Charles’s signature songs when he took its to #1 R&B and #9 pop in 1962.

Ray Charles, ‘Unchain My Heart,’ written by Bobby Sharp

Sharp sold the publishing rights to “Unchain” to band leader Teddy Powell with the stipulation that Powell give Sharp a co-writing credit. Two years later he sold Powell his remaining writer’s share for $1,000. After learning he had been paid by royalties Powell already owed him, Sharp sued to regain his rights; seven years later he settled the suit. Good fortune came his way in 1987 when Joe Cocker had a top 50 single with “Unchain My Heart,” right after Sharp had renewed the copyright on the song in his own name.

Born in 1924 in Topeka, Kansas, Sharp spent his early years in Lawrence, Kansas, then moved to Los Angeles to live with his grandparents. His parents, Louis and Eva, had gone to New York to pursue career dreams they thought could be realized only in that city, given the realities of the Depression years. His father, a concert tenor, won small roles on Broadway and at the famed Lafayette Theatre in Harlem, the same stage where Orson Welles had produced Macbeth with an all-black cast. His mother became active in the National Urban League Guild and a lifelong friend of its founder, Mollie Moon. In 1936, at age 12, Sharp joined his parents in New York.

Despite the hardships of the Depression, the family enjoyed a rich cultural life surrounded by people who were movers and shakers in arts and politics, experiences that would later provide a spark for Bobby’s songwriting talents. Their home at 409 Edgecombe Ave., on top of Harlem’s Sugar Hill, was a gathering place for prominent figures of the Harlem Renaissance. Walter White, founder of the NAACP; Roy Wilkins, NAACP leader for nearly 25 years; and Aaron Douglas, the Topeka-born father of African-American art, all lived at 409 Edgecombe. Duke Ellington was a down-the-street neighbor. Poet Langston Hughes; Eddie Matthews, who performed baritone in Porgy and Bess; and Thurgood Marshall, then a young lawyer, all were part of young Bobby’s extended family. Eva loved to entertain, and with only a hotplate and a few utensils she somehow managed to host large parties for everyone in their two-room apartment. In those days, Depression or not, people would always get up and sing, and Sharp marked his interest in music as stemming from those gatherings.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l2Lt_uowpXk

Joe Cocker, ‘Unchain My Heart,’ on Late Night with David Letterman, 1989

Enlisting in the Army in 1943, Sharp served in the 372nd Infantry regiment stationed in New York City and Ft. Breckenridge, KY, and after getting out of the service, took advantage of the GI Bill to study music, first at the Greenwich House Music school (for the fundamentals) and then at the Manhattan School of Music (for harmony, theory and piano). His impetus for getting serious about learning the craft came from family friend and noted bandleader Sy Oliver, who responded to Bobby’s question, “How can I learn to do what you do–make real songs and write them down?” with a succinct, “Take lessons!”

For the next few years, Sharp ran up and down Broadway and Tin Pan Alley, trying to get songs published. He hung out in bars like Harlem jazz landmark Small’s Paradise, meeting other hungry songwriters. He read books and poems—even the thesaurus—as he wrote tune after tune.

In 1956 he had his recorded his first commercial success as a recording artist with “Baby Girl of Mine,” which was later covered by Ruth Brown. During the ‘50s and ‘60s his tunes were recorded by leading jazz and pop artists, including Sarah Vaughn and Sammy Davis, Jr. and, of course, Ray Charles. Sharp also played several gigs with jazz and big band greats Benny Carter and Jimmie Lunceford, and along the way worked with a score of famous songwriters—Charlie Singleton, Leslie McFarland, Jerry Teifer, Aaron Schroeder, Mel Glazer and Dan and Marvin Fisher. Among his many friendships was the one he struck up with novelist James Baldwin, which resulted in the song “Blues for Mr. Charlie” after Sharp saw Baldwin’s searing Broadway play about race relations in America.

By the time Sharp received his settlement for “Unchain My Heart,” he was retired from the music business and was working in Alameda as a substance abuse counselor at the Westside Community Mental Health Center in San Francisco. He retired in 1988. In 2005 he made his last stand as a musician, releasing his debut CD, The Fantasy Sessions, featuring him playing piano and singing his original songs.

By this time, Bobby had more or less retired from the songwriting business; he’d moved to Alameda, California in 1980 after an earlier short stay in Lafayette, and began working as a substance abuse counselor at the Westside Community Mental Health Center in San Francisco. When he retired from counseling in 1988 it was not with the thought that he would return to music, but his muse beckoned. In 2005, the 81-year-old Sharp released his debut CD, The Fantasy Sessions, a piano-and-vocal album of the artist performing his own songs.

Asked if he had ever met Ray Charles, Sharp said their only encounter came when they were once visiting the same lawyer. “But we didn’t speak because we didn’t know each other.”