Heather Masse and Dick Hyman: the mood is one of quiet, often wistful reflection and introspection centered, naturally, on love, or rather various manifestations of the feeling, from dreamy to unsettling.

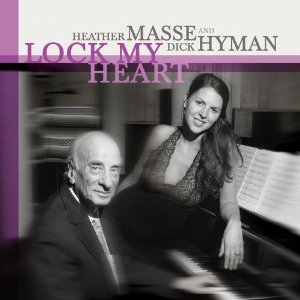

LOCK MY HEART

Heather Masse and Dick Hyman

Red House Records

In this inspired cross-generational conversation, pianist Dick Hyman—legendary by dint of his half-century-plus resume as a revered jazz pianist, classical and film composer (musical director for no less than 13 Woody Allen films), electronic music pioneer (1969’s classic The Age of Electronicus), band leader, arranger—engages coquettish, conservatory trained pop-folk-jazz vocalist Heather Masse (of Canada’s much-honored roots trio Wailin’ Jennys and a Prairie Home Companion favorite) in an intimate piano-and-vocal dialogue concerning the Great American Songbook supplemented by a couple of Masse originals in the GAS style and sensibility. Though there are some frisky, upbeat moments here, the album’s overall mood is one of quiet, often wistful reflection and introspection centered, naturally, on love, or rather various manifestations of the feeling, from dreamy to unsettling. Thus the principals reign in their feelings, exhibiting masterful control, with Hyman crafting spare, empathetic, even sympathetic, punctuation to Masse’s restrained lyrical probings—sultry even as they are deeply interior and often wounded. The tension lifts when an exuberant Hyman gooses the singer into a gently swinging mode on Cole Porter’s “Love for Sale,” and in the middle of a swooning “I Got It Bad and That Ain’t Good” he breaks into a delightful sprint across the keys, but otherwise the duo stays resolutely in a place where the lonely go to commiserate in solitude.

AUDIO CLIP: ‘Since I Fell for You,’ Heather Masse and Dick Hyman, from Lock My Heart

Some classic precedents for a pairing such as this exist, notably Peggy Lee and George Shearing’s Beauty and the Beat! from 1959 (although it was not a piano-and-vocal record but the low-key Shearing quartet with Miss Peggy) and, even more a model, the 1955 pairing of June Christy and pianist-composer-bandleader Stan Kenton on the beautiful Duet album. In fact, Christie, one of the most underrated of all the great classic pop singers of the ‘40s and ‘50s, seems very much a model for Masse’s approach to the tunes here; and wouldn’t you know it, the first selection on Lock My Heart is a version of Rodgers and Hart’s (the liner booklet misspells Rodgers’s name—zut alors!) “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered” that wants to be more ebullient than the singer, in her perplexed state of mind, can possibly be, so it rather ebbs and flows gracefully to an ironic self-congratulatory end (“…bewitched, bothered and bewildered…am I!”) It’s basically the arrangement Hyman brought to Woody’s fabulous Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) as played by Lloyd Nolan in what became a recurring sonic motif as the years passed but it’s also quite similar to the thoughtful, understated arrangement Christy, via her sax-playing arranger husband Bob Cooper and producer Pete Ruggolo, fashioned as the first track on her haunting 1959 long player, Ballads for Night People, which offered a mixed bag of romantic reflections that Lock My Heart emulates.

The defining moment here, however, is not one of the pop-jazz evergreens the duo does to a turn, but Masse’s own stunning “If I Called You,” an instant classic torch number in which the singer’s tender, wistful, breathtakingly controlled delivery exudes both melancholy and hope, as Hyman’s austere, dark and light ruminations magnify the singer’s emotional anxiety as she ponders the possible outcomes of reconnecting with an old flame—the dark wariness in her opening salvo (“If I called you/would you answer/would you remember/my name? If I saw you/would you see me/would you still need me/the same?”), freighted by Hyman’s barely-there piano is an incredible tension-filled moment of complete uncertainty and moreover, a subtext of hopelessness. In the next verse she moves towards the light, her voice lifts, Hyman finds a bright phrase behind her as she muses about whether they could ever “be one” “if I loved you,” and “if I kissed you.” As the verses repeat she affects a slight catch that elevates to a fleeting falsetto (the folk-country element in her voice surfaces here), Hyman’s melody rises to meet her optimism, but when she leaves the track to Hyman with 44 seconds left, she’s still searching for her answers as the quest comes to a quiet, subdued close.

Masse employs that same searching quality to heighten the spiritual drift inherent in a pair of Kurt Weill-Maxwell Anderson numbers, “September Song” and “Lost in the Stars,” both beautifully and subtly realized, but brings bracing fortitude to her despair on a saloon-style blues rendition of Buddy Johnson’s 1945 evergreen “Since I Fell For You,” with Masse’s and Hyman’s approach more in line with the assertive stance Annie Laurie and pianist Paul Gayten took on the 1947 hit version of the song than with more romantic, and better known, renditions by, say, Lenny Welch (a #4 single in 1963), Dinah Washington (1961, recorded with the Quincy Jones Orchestra) and Doris Day (a string-enriched version on her 1963 album Love Him, produced by her son, Terry Melcher). The partners’ dialogue is even better on the bluesy, understated swing they bring to the Gershwins’ “Love is Here to Stay,” an optimistic point of view that Masse infuses with conviction as she’s swooning and playing fancifully with the meter, measuring her moments, singing behind or ahead of Hyman—or right on the beat—in a way that projects a buoyant, upbeat attitude. Elegant and soulful, Lock My Heart actually succeeds in unlocking many secrets of the heart, even as it puzzles over others. Love being a many splendored thing, it appears Hyman and Masse should consider this only a start. There is much more territory to explore, and the results of their further explorations are anxiously awaited.