Charles ‘CD’ Davis: All day and all of the night, blues…

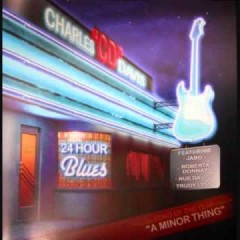

Charles “CD” Davis

Blues House

When he was leading his powerhouse Calvin Owens Blues Orchestra, the late, great Houston bluesman Calvin Owens made any number of inspired hires that strengthened the aggregate and allowed him to realize his fertile musical vision. For nearly a decade guitarist Charles “CD” Davis was one of Owens’s stalwarts on the road and on some choice albums. When Owens passed away in February 2008, CD embarked on a solo career and used his experience with Owens to good advantage to craft a bigger blues with robust horn sections. 24 Hours Blues is his first solo album, a DIY effort, featuring some Owens Blues Orchestra vets and a quartet of gifted singers taking turns on some Davis originals and a few blues/R&B standards. The upshot is immediately arresting, beginning with the first energetic blast of jump blues on Davis’s “Help Me Baby,” and Jabo, the Texas Prince of Zydeco, enters pleading in a Sonny Boy Williamson-like drawl for his woman to give him some dough to pay a fine he’s been assessed for some unspecified transgression, lest he be hoosegow-bound. Davis assists the singer’s petition with some zesty six-string emphasis, a horn section adds staccato bursts of urgency and John Paul Daine surfaces about midway through with a rich, fluid organ solo that sets up CD’s stinging solo. This is about all it took to get 24 Hours Blues in heavy rotation in your faithful friend and narrator’s abode, but the fact is the following 10 cuts are amazing as well–solid band work and to-the-point soloing in service to a host of striking, memorable vocals that grow richer upon repeat listenings.

Charles ‘CD’ Davis’s 24 Hour Blues: a video sampler

It’s likely few will be surprised to find women figuring prominently in the songs here. On the one hand you get Jabo and Rue Davis (the latter alternating between a gritty, muscular delivery and a lighter, sweet-toned, Philippé Wynne attack) ebulliently extolling the virtues of an “Old Fashioned Woman” (another CD original), goosed along by a big, energetic blast from Bruce Middleton’s sax; Rue getting lowdown about his lustful ways in a grinding, horn-fueled, double-entendre gem, “When Mama Leaves Town,” in which the horn he sings about is decidedly not of the musical kind and, in one of the album’s most striking moments and most affecting arrangements (which takes into account the tune’s country origins), appropriates a bit of Ray Charles’s ache and, as the horns surge soothingly behind him, adds his own ironic perspective to magnify the hurt of “You Don’t Know Me,” the classic penned by Eddy Arnold but definitively rendered in lush, orchestrated terms by Brother Ray in 1962 on his groundbreaking Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music. Fingerpicking spare, Delta-style accompaniment, CD gives Jabo his own moment of abject desolation with an original forlorn lament, “Lonely Man Blues,” that he delivers in a voice both plaintive and assertive, uncannily reminiscent of Big Bill Broonzy’s style.

Trudy Lynn

Demanding a fair hearing, the distaff side gets it, and how. San Francisco-based jazz chanteuse Roberta Donnay has two unforgettable turns here: a swaggering, deliciously sultry rendering of Henry Hipkins’s “That’s How I Learned to Sing the Blues,” a blues rarity in which the woman admits to undermining a relationship (“you find a good guy, then treat him wrong/then be sorry about it when he’s gone/you’ll say come back, he’ll refuse/that’s how I learned to sing the blues”); however, in this slow boiling, shuffling arrangement with intimations of le jazz hot (especially in CD’s Django-like guitar), Ms. Donnay sounds chagrined but not altogether remorseful; with CD she co-wrote the album’s penultimate tune, “A Minor Thing,” a lonely, late-night, Waits-style rumination she confesses in a boozy drawl rising to a wounded cry in the chorus, as strings gently ascend in long, flowing lines behind her, a muted trumpet cries and Davis’s guitar punctuates her misery with heated stabs. Sassier and more muscular-voiced, veteran blues belter Trudy Lynn practically mounts a pulpit in preaching lessons learned the hard way from a failed romance in “Still Got the Blues,” a sermon lent added profundity by an absolutely searing sax solo and CD’s howling, merciless guitar. Later, though, she gives Rue Davis a run for his money in the bawdy blues category when she and the band kick into a driving groove and bring home the pre-gospel Thomas A. Dorsey’s “It’s Tight Like That” with all the naughtiness its writer intended before he got religion. With the guitar and band strutting behind her and a responsive chorus shadowing her, Ms. Lynn has so much fun wallowing in the lyrics’ suggestiveness she borders on committing at least a misdemeanor.

At the end Davis gives himself the spotlight for an original instrumental, “Blues for My Father,” nearly five minutes of rising and receding tension, now reflective, now heated, backed by some tasty, medium-cool organ work by John Paul Daine, and gut-punch drumming courtesy Marvin Sparks. After giving the stage, so to speak, to the outstanding singers he assembled for this project, it’s right for Davis himself to have the last word. And the word is good. Encore!