Dispatched by hired assassins in 1682, the 17th century composer gained favor with the power elite of his time and aroused the enmity of same. In the five years preceding his bloody demise, though, Stradella composed an imposing body of work that influenced succeeding generations of classical composers (notably Handel) and which retains all its evocative, spiritual allure in the 21st century. Herewith an appreciation and reclamation in four parts.

Introduction

One of the most enigmatic, colorful and gifted artists of his time, the 17th century Italian composer Alessandro Stradella lived a life tailor-made for biographers. Not only was his music highly regarded and even groundbreaking (his Wikipedia entry makes the bold statement that “he enjoyed a dazzling career as a freelance composer, writing on commission, and collaborating with distinguished poets, producing over three hundred works in a variety of genres” and points out, correctly, that no less a titan than George Frederic Handel saw fit to lift–or “exploit–portions of Stradella’s music for his celebrated biblical oratorio Israel in Egypt, about which more later) but his habit of mixing pleasure with business, especially when it came to women, led directly to two attempts on his life, the last of which was successful, when three hired killers murdered him in 1682 (he wrote most of his most famous works between 1677 and 1682, between attempts on his life, which, one supposes, might have spurred his creative impulses).

Unfortunately, documentation of that life, lived entirely in the 17th century, is either sparse or contradictory, or, indeed, non-existent. Even the diligent research documented by author Carolyn Gianturco in her biography (the most recent work on the subject), Alessandro Stradella 1639-1683: His Life and Music (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994), has been found somewhat wanting by the Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music. Still, Ms. Gianturco, despite some missteps in chronicling and appraising Stradella’s music, did correct the record in some instances–finding evidence for his birth being in 1639 rather than the formerly accepted date of 1644, for instance–and at least was a valiant effort at restoring the then-obscure composer to the lofty position among his contemporaries that he enjoyed in his own time. Prior to Ms. Gianturco’s book, the only in-depth examinations of Stradella’s life and work came in 1903, in Rupert Hughes’s Love Affairs of Great Musicians, Vol. 1, in a chapter titled “The Strange Adventures of Stradella”; and six years later, in 1909, in fictional form in Stradella, a novel by a then-popular Italian-born author, Francis Marion Crawford, who developed a style blending romanticism and realism in his historically-based works. Stradella was one of his lesser efforts; his most popular and adventurous work was a series of novels known as the Saracinesca, named after the Italian family at the center of the tales. The first of these, Don Orsino (1892), observed its characters’ tribulations in the wake of a real estate bubble not unlike the one that burst in the U.S. in the fall of 2008; the fourth book in the series bore the resonant title Corleone (published in 1897), and is the first major literary treatment of Mafia life (available to read free online here); his 1900 novel, Rulers of the South, ended with a chapter about the Sicilian Mafia.

From all these sources, a general outline of Stradella’s life goes something like this (Source: HOASM):

The Italian composer Alessandro Stradella was the son of a Cavaliere Marc Antonio Stradella of Piacenza, who in 1642-1643 was vice-marchese and governor of Vignola for Prince Boncompagni, who did not wish to live in the dominions from which he took the title of Marchese di Vignola. He was deprived of his office in 1643 for having surrendered the castle to the papal troops, although it might have sustained a siege of several days and the help of the Duke of Modena was expected. An elder brother of Alessandro, Francesco by name, became a member of the Augustinian order, and seems to have enjoyed the protection of the house of Este.

Stradella, Sonata de viole (Movements 1-4: Adagio [Allegro], Allegretto, Adagio [Allegro], Gigue

Alessandro is supposed to have been born about 1639, probably at Nepi, although the family moved to Vignola, or Monfestino, a town on the road from Modena to Pistoja, whither his father retired after his dismissal; but no records of his birth have come to light. He studied in Bologna before 1664, although it is not known with whom. He probably left his birthplace for good in 1664, and was certainly in Rome by 1667. At this time he was writing stage works, oratorios, prologues and intermezzi to operas, and motets. He came from a noble family, and in consequence was not dependent on any patron or institution, but his compositions were written on commission. Scandal struck when in 1669 he was involved in an attempt to embezzle funds from the church, and he left Rome for a time until it died down. Around 1670-1672, his Il Biante, an azione drammatica, was performed in honor of Pope Clement X. He was again compelled to leave Rome for Venice in 1677 after angering Cardinal Alderan Cibo. Documents in the archives at Turin relate that in 1677 he arrived there with the mistress of Alvise Contarini, with whom he had eloped from Venice. Contarini demanded that both should be given up to him, or failing that, that Stradella should not be allowed to exercise his profession until the lady had been either placed in a convent or made his legitimate wife. Stradella was protected by the regent of Savoy, the duchess Giovanni Battista de Nemours, and the Contarini family, indignant at his audacity, sent two hired assassins to Turin, by whom Stradella was wounded but not murdered.

We hear of Stradella last at Genoa. There his comic opera Il trespolo tutore was performed ca. 1677, La Forza deli amor paterno, in 1678 and Le gare dell’ amor eroica in 1679, and his last composition, Ii Barcheggio (i.e. a Water-Music), was performed on June 16, 1681 in honor of the marriage of Carlo Spinola and Paola Brignole, which was solemnized on July 6 of the same year. Documents in the archives at Modena inform us that in February 1682 Stradella was murdered at Genoa by three brothers named Lomellini, whose married sister he had seduced.

His vocal works include seven operas, prologues, intermezzi, a Mass, motets, cantatas, arias, and canzonettas. Most of his 27 instrumental works are sonate da chiesa. His Sonata di viole is the earliest known concerto grosso.

Our appreciation, if you will, of Stradella is in four parts: Part I, the chapter “The Strange Adventures of Stradella,” from Rupert Hughes’s 1903 book, Love Affairs of Great Musicians, Vol. 1; Part II, a more recent, critical biographical entry on Stradella at NNDB (“tracking the entire world”) incorporating facts unearthed and verified well after Hughes’s volume was published in 1903; Part III: an excerpt from audio pioneer and general intellectual gadfly Sedley Taylor’s 1873 analysis of Handel’s borrowings from Stradella’s music in the former’s magnificent biblical oratorio Israel in Egypt; Part IV: an excerpt from Chapter II of the novel Stradella, published in 1909 by best selling author F. Marion Crawford.

PART I

The Strange Adventures of Stradella

From Love Affairs of Great Musicians, Vol. 1

By Rupert Hughes

Published 1903

Published at Project Gutenberg

(Note: Though Rupert Hughes is the author of Love Affairs of Great Musicians, his entry on Stradella is taken verbatim from an account published by Sir John Hawkins, as Hughes freely admits in his first paragraph.)

There are historians, sour and cynical, who have tried to contradict the truth of the life story of Stradella as Bourdelot tells it in his “Histoire de la Musique et de ses Effets,” but they cannot offer us any satisfactory substitute in its place, and without troubling to give their merely destructive complaints, and without attempting to improve upon the pompously fascinating English of old Sir John Hawkins, I will quote the story for your delectation.

Certain it is that there was a composer named Stradella, and that he was an opera composer to the Venetian Republic, as well as a frequent singer upon the stage to his own harp accompaniments. He occupies a position in musical history of some importance. The following story of his adventures is no more improbable than many a story we read in the daily newspapers—and surely no one could question the credibility of the daily newspapers. But here is the story as Hawkins tells it. As the cook-books say, salt it to your taste.

“His character as a musician was so high at Venice, that all who were desirous of excelling in the science were solicitous to become his pupils. Among the many whom he had the instruction of, was one, a young lady of a noble family of Rome, named Hortensia, who, notwithstanding her illustrious descent, submitted to live in a criminal intimacy with a Venetian nobleman. The frequent access of Stradella to this lady, and the many opportunities he had of being alone with her, produced in them both such an affection for each other, that they agreed to go off together for Rome. In consequence of this resolution they embarked in a very fine night, and by the favour of the wind effected their escape.

Alessandro Stradella: Sonata a otto Viole con una Tromba in D major/The Parley of Instruments: [natural trumpet, Coro I: violin, two violas, bass violin; Coro II: violin, two violas, bass violin and basso continuo]

“Upon the discovery of the lady’s flight, the Venetian had recourse to the usual method in that country of obtaining satisfaction for real or supposed injuries: he despatched two assassins, with instructions to murder both Stradella and the lady, giving them a sum of money in hand, and a promise of a larger if they succeeded in the attempt. Being arrived at Naples, the assassins received intelligence that those whom they were in pursuit of were at Rome, where the lady passed as the wife of Stradella. Upon this they determined to execute their commission, wrote to their employer, requesting letters of recommendation to the Venetian embassador at Rome, in order to secure an asylum for them to fly to, as soon as the deed should be perpetrated.

“Upon the receipt of letters for this purpose, the assassins made the best of their way toward Rome; and being arrived there, they learned that on the morrow, at five in the evening, Stradella was to give an oratorio in the church of San Giovanni Laterano. They failed not to be present at the performance, and had concerted to follow Stradella and his mistress out of the church, and, seizing a convenient opportunity, to make the blow. The performance was now begun, and these men had nothing to do but to watch the motions of Stradella, and attend to the music, which they had scarce begun to hear, before the suggestions of humanity began to operate upon their minds; they were seized with remorse, and reflected with horror on the thought of depriving of his life a man capable of giving to his auditors such pleasure as they had just then felt.

“In short, they desisted from their purpose, and determined, instead of taking away his life, to exert their endeavours for the preservation of it; they waited for his coming out of the church, and courteously addressed him and the lady, who was by his side, first returning him thanks for the pleasure they had received at hearing his music, and informed them both of the errand they had been sent upon; expatiating upon the irresistible charms, which of savages had made them men, and had rendered it impossible for them to effect their execrable purpose; and concluded with their earnest advice that Stradella and the lady should both depart from Rome the next day, themselves promising to deceive their employer, and forego the remainder part of their reward, by making him believe that Stradella and his lady had quitted Rome on the morning of their arrival.

“Having thus escaped the malice of their enemy, the two lovers took an immediate resolution to fly for safety to Turin, and soon arrived there. The assassins being returned to Venice, reported to their employer that Stradella and Hortensia had fled from Rome, and taken shelter in the city of Turin, a place where the laws were very severe, and which, excepting the houses of embassadors, afforded no protection for murderers; they represented to him the difficulty of getting these two persons assassinated, and, for their own parts, notwithstanding their engagements, declined the enterprise. This disappointment, instead of allaying, served to sharpen the resentment of the Venetian: he had found means to attach to his interest the father of Hortensia, and, by various arguments, to inspire him with a resolution to become the murderer of his own daughter. With this old man, no less malevolent and vindictive than himself, the Venetian associated two ruffians, and dispatched them all three to Turin, fully inspired with a resolution of stabbing Stradella and the old man’s daughter wherever they found them. The Venetian also furnished them with letters from Mons. l’Abbé d’Estrades, then embassador of France at Venice, addressed to the Marquis of Villars, the French embassador at Turin. The purport of these letters was a recommendation of the bearers of them, who were therein represented to be merchants, to the protection of the embassador, if at any time they should stand in need of it.

“The Duchess of Savoy was at that time regent; and she having been informed of the arrival of Stradella and Hortensia, and the occasion of their precipitate flight from Rome; and knowing the vindictive temper of the Venetians, placed the lady in a convent, and retained Stradella in her palace as her principal musician. In a situation of such security as this seemed to be, Stradella’s fears for the safety of himself and his mistress began to abate, till one evening, walking for the air upon the ramparts of the city, he was set upon by the three assassins above mentioned, that is to say, the father of Hortensia, and the two ruffians, who each gave him a stab with a dagger in the breast, and immediately betook themselves to the house of the French embassador as to a sanctuary.

“The attack on Stradella having been made in the sight of numbers of people, who were walking in the same place, occasioned an uproar in the city, which soon reached the ears of the duchess: she ordered the gates to be shut, and diligent search to be made for the three assassins; and being informed that they had taken refuge in the house of the French embassador, she went to demand them. The embassador insisting on the privileges which those of his function claimed from the law of nations, refused to deliver them up. In the interim Stradella was cured of his wounds, and the Marquis de Villars, to make short of the question about privilege, and the rights of embassadors, suffered the assassins to escape.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0gv20qH4cu4

Stradella, Furie del nero Tartaro; Riccardo Ristori, basso

“From this time, finding himself disappointed of his revenge, but not the least abated in his ardour to accomplish it, this implacable Venetian contented himself with setting spies to watch the motions of Stradella. A year was elapsed after the cure of his wounds; no fresh disturbance had been given to him, and he thought himself secure from any further attempts on his life. The duchess regent, who was concerned for the honour of her sex, and the happiness of two persons who had suffered so much, and seemed to have been born for each other, joined the hands of Stradella and his beloved Hortensia, and they were married.

“After the ceremony Stradella and his wife having a desire to visit the port of Genoa, went thither with a resolution to return to Turin: the assassins having intelligence of their departure, followed them close at their heels. Stradella and his wife, it is true, reached Genoa, but the morning after their arrival these three execrable villains rushed into their chamber, and stabbed each to the heart. The murderers had taken care to secure a bark which lay in the port; to this they retreated, and made their escape from justice, and were never heard of more.

“Mr. Berenclow says that when the report of Stradella’s assassination reached the ears of Purcell, and he was informed jealousy was the motive to it, he lamented his fate exceedingly; and, in regard of his great merit as a musician, said he could have forgiven him any injury in that kind; which, adds the relater, ‘those who remember how lovingly Mr. Purcell lived with his wife, or rather what a loving wife she proved to him, may understand without farther explication.'”

PART II

Stradella Updated

A more recent, critical biographical entry on Stradella at NNDB (“tracking the entire world”) makes use of facts unearthed and verified well after Hughes’s volume was published in 1903. Thus a corrective to the conventional wisdom regarding the composer’s life’s journey. To wit:

Italian composer, one of the most accomplished musicians of the 17th century. The hitherto generally accepted story of his life was first circumstantially narrated in Bonnet-Bourdelot’s Histoire de la musique et de ses effets (Paris, 1715). According to this account, Stradella not only produced some successful operas at Venice, but also attained so great a reputation by the beauty of his voice that a Venetian nobleman engaged him to instruct his mistress, Ortensia, in singing. Stradella, the narrative goes on to say, shamefully betrayed his trust, and eloped with Ortensia to Rome, to where the outraged Venetian sent two paid bravi to put him to death. On their arrival in Rome the assassins learned that Stradella had just completed a new oratorio, over the performance of which he was to preside on the following day at S. Giovanni in Laterano. Taking advantage of this circumstance, they determined to kill him as he left the church; but the beauty of the music affected them so deeply that their hearts failed them at the critical moment, and, confessing their treachery, they entreated the composer to ensure his safety by quitting Rome immediately. Thereupon Stradella fled with Ortensia to Turin, where, notwithstanding the favor shown to him by the regent of Savoy, he was attacked one night by another band of assassins, who, headed by Ortensia’s father, left him on the ramparts for dead. Through the connivance of the French ambassador the ruffians succeeded in making their escape; and in the meantime Stradella, recovering from his wounds, married Ortensia, by consent of the regent, and removed with her to Genoa. Here he believed himself safe; but a year later he and Ortensia were murdered in their house by a third party of assassins in the pay of the implacable Venetian.

Later research has shown that Stradella was the son of a Cavaliere Marc’antonio Stradella of Piacenza, who in 1642-43 was vice-marchese and governor of Vignola for Prince Boncompagni, who did not wish to live in the dominions from which he took the title of marchese di Vignola. He was deprived of his office in 1643 for having surrendered the castle to the papal troops, although it might have sustained a siege of several days and the help of the duke of Modena was expected. An elder brother of Alessandro, Francesco by name, became a member of the Augustinian order, and seems to have enjoyed the protection of the house of Este. Alessandro is supposed to have been born about 1645 or earlier, probably at Vignola, or Monfestino, a town on the road from Modena to Pistoja, to which his father retired after his dismissal; but no records of his birth have come to light in either of these places. The first certain date in his life is 1672, in which year he composed a prologue for the performance of Cesti’s opera La Dori at Rome; and we may conclude that he spent a considerable time at Rome about this period, since his cantatas and other compositions contain frequent allusions to Rome and noble Roman families. There is, however, no proof that he ever performed the oratorio S. Giovanni Battista in the Lateran. Documents in the archives at Turin relate that in 1677 he arrived there with the mistress of Alvise Contarini, with whom he had eloped from Venice. Contarini demanded that both should be given up to him, or failing that, that Stradella should not be allowed to exercise his profession until the lady had been either placed in a convent or made his legitimate wife. Stradella was protected by the regent of Savoy, the duchess Giovanni Battista de Nemours, and the Contarini family, indignant at his audacity, sent two hired assassins to Turin, by whom Stradella was wounded but not murdered. We hear of Stradella last at Genoa. An opera by him, La Forza dell’ amor paterno, was given there in 1678, and his last composition, Il Barcheggio (a “Water-Music”), was performed on the 16th of June 1681 in honor of the marriage of Carlo Spinola and Paola Brignole, which was solemnized on the 6th of July of the same year. Documents in the archives at Modena inform us that in February 1682 Stradella was murdered at Genoa by three brothers of the name of Lomellini, whose sister he had seduced.

Stradella, Serenata a 3 ‘Qual prodigio’; Basia Retchitzka, Annelies Gamper, soprani; James Loomis, basso; Luciano Sgrizzi, cembalo; Società Cameristica di Lugano, direttore Edwin Loeher

It is extremely improbable that Stradella had any great reputation as a singer, since the great Italian singers of the 17th century were almost exclusively castrati; but he may well have been a teacher of singing, and he appears to have instructed his lady pupils in Genoa on the harpsichord. He is principally important as a composer of operas and chamber-cantatas, although compared with his contemporaries his output was small. In spite of his dissolute life his command of the technique of composition was remarkable, and his gift of melodic invention almost equal to that of Alessandro Scarlatti, who in his early years was much influenced by Stradella. His best operas are Il Floridoro, also known as Il Moro per amore, and Il Trespolo tutore, a comic opera in three acts which worthily carried on the best traditions of Florentine and Roman comic opera in the 17th century. His church music, on which his reputation has generally been based, is of less importance, though the well-known oratorio S. Giovanni Battista displays the same skill in construction and orchestration (so far as the limited means at his disposal permitted) as the operas. A serenata for voices and two orchestras, Qual prodigo ch’io, miri, was used by Handel as the basis of several numbers in Israel in Egypt, and was printed by Chrysander (Leipzig, 1888); the manuscript, however, formerly in the possession of Victor Schoelcher, from which Chrysander made his copy, has entirely disappeared. The well-known aria Pietà, signore, also sung to the words Se i miei sospiri, cannot possibly be a work of Stradella, and there is every reason to suppose that it was composed by Fétis, Niedermeyer or Rossini.

The finest collection of Stradella’s works extant is that at the Biblioteca Estense at Modena, which contains 148 manuscripts, including four operas, six oratorios and several other compositions of a semidramatic character. A collection of cantate a voce sola was bequeathed by the Contarini family to the library of St. Mark at Venice; and some manuscripts are also preserved at Naples and in Paris. Eight madrigals, three duets, and a sonata for two violins and bass will be found among the Additional MSS. at the British Museum, five pieces among the Harleian MSS., and eight cantatas and a motet among those in the library at Christ Church, Oxford. The Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge possesses a large number of his chamber-cantatas and duets.

PART III

Handel, in Stradella’s Debt

(So just how much of Stradella’s work did Handel “exploit” for his biblical oratorio Israel in Egypt? In January 1906 intellectual gadfly Sedley Taylor, a recognized authority on sound and music [who in fact published a book titled Sound and Music in 1873 that introduced English readers to the advanced acoustical theories of Hermann Helmholtz and became, as the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography notes, “a standard textbook until the twentieth century”], published a detailed analysis of Handel’s borrowings from and transformation of Stradella’s music for his biblical oratorio Israel in Egypt. Absent the actual sheet music Taylor used to illustrate his points, the text below is from Taylor’s book titled The indebtedness of Handel to works by other composers: a presentation of evidence published in January 1906. The complete book is available as a free e-book at Google Books).

The fact of Handel’s borrowings from other composers’ works, and rearrangements of his own, may now, I think, be regarded as established, and we have to consider what is a still more interesting and instructive subject, viz. how he dealt with his sources, what, kinds of effect he succeeded in working them up into, and what is the result of comparisons instituted between the merits of his completed work and those of the compositions utilized in their construction.

It happens that Handel’s choral masterpiece Israel in Egypt affords an unique opportunity of seeing his mode of procedure carried out on a great scale, and with results of stupendous grandeur which dwarf into insignificance the, often very meritorious, compositions used in producing them. I propose, therefore, in order to bring all this out, to make a full examination of that truly astonishing work in reference to the various sources which are now known to have been drawn upon during its construction.

No antecedent sources are known to exist for the first three numbers, viz. the recitative ” Now there arose,” the double chorus ” And the children of Israel sighed” and the recitative “Then sent He Moses.” No. 4, the chorus “They loathed to drink of the river, He turned their waters into blood ” is formed out of an organ-fugue, No. 5 of a set of six which Handel wrote in 1720 (1) but did not publish until 1735, three years before he composed Israel in Egypt. The fugue, which stands in the key of A minor, consists of 74 bars. Handel cut out 32 of these and transposed the rest, extensively remodeled, into the key of G minor. (1) Chrysandor: Life of Handel, vol, III p. 201.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VX09aJLNFMw

Handel, Israel in Egypt: He gave them hailstones for rain, He sent a thick darkness. Leeds Festival Chorus, English Chamber Orchestra, direction Sir Charles Mackerras

In turning this old organ-fugue into a chorus Handel has evidently effected great improvements in the disposition of his parts, especially in bars 22, 23, 33-36, 38-40. But a power of a much higher order is recognizable in the imagination which could discern in a not exactly inspiring organ-piece the makings of a choral picture so gruesomely descriptive as that which Handel has succeeded in producing. It suffices to play over on the pianoforte first the passages quoted from the organ-fugue and then the chorus, giving effect in the latter to the entries of the subject on ” They loathed ” and the descending chromatic scale-notes, in order to realize how astonishing this power is.

The Air “Their land brought forth frogs” has not been shown to be derived from any antecedent source.

The ensuing double chorus, (No. 6), “He spake the word,” is taken, as far as the choral parts are concerned, with few, but very effective, improvements, from a secular serenata composed by Alessandro Stradella. This will, therefore, be the proper place to tell the little that is known about that composer, from whom, as will presently be seen, Handel took a good deal of material.

Handel, Israel in Egypt, Part 1 Chorus: He rebuked the Red Sea and it was dried up

Alessandro Stradella was a celebrated Italian composer in the seventeenth century and became the central figure of a romantic story which was afterwards put upon the stage as an opera.(1) Subsequent researches having reduced the historical value of this story to zero, we learn from Herr Eitner* that the course of Stradella’s life is “wrapped in complete darkness.” The dates of his birth and death are unknown and nothing of him but a large number of compositions appears to remain.

A score of one of these, entitled Il Barcheggio, bears evidence that it was composed for a wedding-festivity which took place in 1681. This date is written on two pages of the score, as is also a statement that Il Barcheggio was Stradella’s last sinfonia or composizione.* No question of priority, therefore, can arise between a work by Handel and one by Stradella, whose last composition is thus fixed at a date four years earlier than Handel’s birth.

Dr. Chrysander published, in 1888, as No. 3 of his “Supplements,” (4), an edition of the serenata by Stradella which concerns us here, together with indications of where Handel had used it. The movement on which the chorus “He spake the word” is built up is an orchestral interlude for two separate groups of instruments, one scored for two violins and a bass, the other for a quartet of strings with doubled parts. These two groups alternate with each other throughout the move ment in phrases varying from half-a-bar to two bars in length. This arrangement may well have suggested to Handel the idea of turning the movement into a double chorus, which is what he did by adding a fourth part to Stradella’s smaller group, revising his counterpoint with occasional masterly touches and composing descriptive passages of orchestral accompaniment.

(1) Set to music both by Flotow and by Niedermeyer in the same year, 1837, (Art. in Grove’s Dictionary.) *Musikalieches Qnellen-Lezicon, article ‘ Stradella.’ •Grove’s Dictionary. 1st ed. vol. III. p. 723 note 4. (4) See ante p. xi.

Handel opens his chorus with seven bars based on Stradella’s material, bat in five of these the sopranos and altos alone take part. Thus a sforzando effect is produced when, after bar 8, where continuous borrowing from Stradella begins, mixed-voices harmony is for the first time heard.

In bar 12 Handel obtains increased vigour by bis added D in the first choir and by lowering Stradella’s semi-quavers an octave.

In bar 17 the two choruses overlap on the 3rd beat with a greatly enhanced effect, which is heard again in bars 22, 23 and 25.

In bars 22 and 23 there is a fine free movement in the two soprano parts where Stradella has none.

In bars 28 and 29 the counterpoint is immensely improved.

In the last beat of bar 30 and the first of bar 31 a wonderful impression of finality is conveyed by the Octave rise of the basses and the Fifth drop of the sopranos on “He spake,” where nothing of the kind exists in Stradella. Handel has reinforced these improvements by an accompaniment of florid violin-passages in demi-semiquavers, which pervades the whole chorus, to suggest the buzzing of the flies, and in bars 31-34 by a moving bass in semi-quavers, to illustrate the heavier calamity of the locusts coming “without number ” to ” devour the fruits of the ground.” Chrysander remarks that ” the originality of the chorus rests upon this accompaniment” (1) Only if the narrowest and most literal meaning be assigned to “originality ” can I admit this. In a higher sense true originality appears to me to be required in order to discern in Stradella’s simple, and a trifle jog-trot, piece of chamber-music the potentiality of being developed into a chorus which should present with almost terrifying energy the issuing of the supreme behest and its dire fulfillment As was well said half-a-century ago:

“The imitation of the buzzing of insects in the accompaniment to Handel’s chorus in Israel in Egypt.” He spake the word and there came all manner of flies were merely an ingenious trifle, but for the superlative grandeur of the choral passages which tell of the Almighty fiat.”*

The orchestral introduction to the next, the famous “Hailstone,” chorus, (No. 7), probably the greatest popular favourite of the entire oratorio, is made up of eleven bars taken from the opening of the 1 Sinfonia ‘ to Stradella’s Serenata, and four from that to a bass song in the same work, the former standing in the key of D, the latter in that of A Handel’s contribution to his own prelude consists at most in three original bars as against fifteen taken from Stradella.

(1) Life of Handel vol IIL p. 66.; *Tovnsend : “Visit of Handel to Dublin:” Dublin 1852 p. 92.

The fine flowing passage set to the words “ran along upon the ground ” is written on a bass in Stradella’s song, the second bar of which had already appeared in the symphony to it, and been incorporated in Handel’s sixteenth bar. Finally an energetic phrase is taken from the same song, and its force greatly intensified by the repetition of its first bar and the extension of its descending scale.

Handel, Israel in Egypt, The People Shall Hear and Be Afraid; performed by John Eliot Gardiner and the Monteverdi Choir and Orchestra, with William Kendall, J. Clarkson, B. Gordon, Christopher Royall, Marilyn Sansom, Ashley Stafford, Paul Elliott, Elisabeth Priday, Stephen Varcoe, M. Troth, Charles [bass vocal] Stewart, Alistair Ross, D. Greene, Malcolm Hicks, Jean Knibbs.

Of the chorus proper, apart from the opening symphony (which is repeated at the close, cut down to half its length and with no original matter introduced) nearly one-half is mere rearrangement, or contrapuntal development, of the phrases from Stradella which have been set out in Ex. 28.

It cannot be denied that these supply the most interesting material to be found in the chorus, but there remain as Handel’s property the vigorous alternating entries of the two choirs and the wonderful choral shouts of ” fire ” first with simple accompaniment and at last with a magnificent moving bass. But, when all has been said, we are no nearer to understanding how it was that Handel could detect the possibilities which lay hid in these, to ordinary observers rather uninteresting passages, and work them up with other matter of his own into a colossal soundpicture, vivid, sublime, instinct with a terrible energy and perfectly homogeneous from one end to the other. While we must, I think, rank the power of doing this less highly than that of producing an entirely original composition of equal merit, the name of genius can hardly be refused to it when it attains such results as are embodied in the “Hailstone chorus.”

Passing over No. 8, the chorus ” He sent a thick darkness,” which appears to be original, we come to No. 9, the chorus ” He smote all the first-born of Egypt.” The subjects of it are taken from another of the set of organ-fugues mentioned above,1 but, as the treatment of them diverges widely after their first entry, it will suffice to compare the opening eight bars of the two compositions.

The next chorus (No. 10), “But as for His people,” consists, of 168 bars of which 117 appear to be Handel’s property, while 51 are evidently made out of a phrase in a soprano song in Stradella’s Serenata which Handel has transferred bodily, with its canonic accompaniment shortened by one bar.

Handel first makes his Altos sing this phrase in the key of G and then his Sopranos in that of C (as in the Example): next the Tenors sing it in the same key, the Altos chiming in at the end with an ingeniously constructed little imitative tag, after which the Basses sing the phrase and the Tenors the tag. Finally the Sopranos sing the phrase again in the key of D, the other voices taking over Stradella’s figure of accompaniment, shortened as before, and the Sopranos emphasizing the close by an octave drop simultaneously with the entry of the Basses.

In this manner, if we count in two bars of orchestral continuation, Stradella’s phrase of eight bars is elongated into thirty-nine. Later on in the chorus his bit of canonic imitation appears first for the Basses and Tenors and then for the Altos and Sopranos, which, with two more bars of orchestral finish, complete the tale of fifty-one bars which Handel has contrived to spin out of Stradella’s phrase of less than nine bars. But for all that, the effect produced is unflaggingly fresh and completely congruous with the words sung.

The chorus which comes next in order, (No. 11), “Egypt was glad when they departed ” presents an instance of appropriation which is extreme even for HandeL A celebrated German organist Johann Caspar Kerl (1628-1693) published at Munich in 1686, one year after Handel’s birth, a work entitled Modulatio Organica super Magnificat. A canzona contained in that work reappears, with hardly any alterations beyond what were required to adapt an organ-piece for performance by voices, as the chorus now before us.

Handel, Israel in Egypt, Finale: The Lord shall reign for ever and ever, by the Monteverdi Choir

As Kerl published his canzona in 1686, when Handel was only one year old, his priority is beyond dispute. Curiously enough Sir John Hawkins, in his “History of Music,” which appeared in 1776, published an inaccurate version of this canzona “as a specimen of Kerl’s style of composition for the organ,” (1) evidently in entire ignorance of the use to which Handel had turned it, 38 years earlier, in Israel in Egypt.

Fortunately nothing prevents our regarding the next chorus (No. 12), ” He rebuked the Red Sea,” as anything but what it has always been taken for–a tremendous stroke of original genius. The remark attributed, I think, to Beethoven, that when Handel cho3e, he could “strike like a thunderbolt,” thoroughly applies to these mighty eight bars. Nor does the inspiration take any lower level in that superb oceanic commingling of sublimity and loveliness, the chorus (No. 13) “He led them through the deep,” though for its original form Handel went back more than thirty years to a work which ho had composed in Rome in 1707,5 a setting of Psalm CX. in Latin (Dixit Dominus) for a five-part chorus, orchestra and organ. A double fugue in this work to the words “Tu es sacerdos in æternum secundum ordinem Melchisedech” contains the germ from which the chorus now under consideration was developed.

The short, but extraordinarily impressive, double chorus (No. 15), “And Israel saw that great work,” contains such palpable discharges of creative energy that it may, I hope, be set down to Handel’s sole initiative. It is followed by the chorus (No. 16), “And believed the Lord,” consisting of 63 bars, 46 of which, i.e. nearly three-quarters of the whole chorus, are, with but small modification, taken from, or built up on, a soprano song accompanied by two violins and a bass in Stradella’s Serenata.

PART IV

‘There is love between us. We have seen it in each other’s eyes ever since we first met, we have heard it in one another’s voices every day!’

In this excerpt from Chapter II of the novel Stradella, published in 1909 by best selling author F. Marion Crawford, the popular composer and teacher has been retained by Senator Michele Pignaver of Venice to teach music (specifically, the Senator’s own half-baked songs, not Stradella’s accomplished works) to his 17-year-old niece Ortensia, whom the Senator intended to make his wife. Ortensia, whom Crawford describes as having “the first bloom of young womanhood…already on here cheek,” even as “the frosts of childhood’s morning had not melted from her maiden heart,” found herself inexorably drawn to her teacher, as he was to her. Theirs was a delicate dance around the Senator’s curiosities about their progress, but they found an ally in Ortensia’s nurse, Pina, who caught on to their mutual attraction and discreetly provided cover for the budding romance to flower, if only to spite the Senator, whom she hated “for reasons of her own, which he had either forgotten, or which he disregarded because, in his opinion, she was under the greatest obligation to the house. Pina’s hatred of her master was more sincere, if possible, than her affection for Ortensia, and her contempt for his intelligence was almost as profound as his own belief in its superiority over that of other men.” At this point in the story, Stradella arrives at the Senator’s home for his final scheduled lesson with the fair maid, fully intent on making his feelings known to his pupil.

The Senator introduces Stradella to his niece, Ortensia: ‘This is the celebrated Maestro Alessandro Stradella of Naples.’

Stradella found himself faced by a most unexpected circumstance. He was not only in love; that had happened to him at regular intervals ever since he had been barely fourteen years old, when a beautiful Neapolitan princess heard him sing and threw her magnificent arms round his neck, kissing him, and laughing when he kissed her in return; and she had made him the spoilt darling of her villa at Posilippo for more than three weeks.

Since then he had regarded his love affairs very much as he looked upon the weather, as an irregular succession of fine days, dark days, and stormy days. When he was happily in love, it was a fine day; when unhappily, it was stormy; when not at all, it was dull-very dull. But hitherto it had never occurred to him that any one of the three conditions could last. Like Goethe, he had never begun a love-affair without instinctively foreseeing the end, and hoping that it might be painless.

But to his amazement, though he had been prepared to be as cheerfully cynical and as keen after enjoyment as usual, he now felt, almost from the first, that there was no end in sight, or even to be imagined. The beginnings had not been new to him; it was not the first time that beauty had stirred his pulse, or that a face had awakened sympathy in that romantic region of feeling between heart and soul which is as far above the brute animal as it is below the pure spirit. Before now his voice had brought fire to a woman’s eyes, and her lips had parted with unspoken promises of delight. That was what had happened on the first day when Pina had left him alone with Ortensia and he had sung to her; that had all been normal and natural, and only not dull because the fountain of youth was full and overflowing; that might have happened to any man between twenty and thirty.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mb3aVm_Hv0A

Stradella, Oratorio di S. Pelagia (estratti). Pelagia–Laura Antonaz, soprano; Nonno–Fabio Furnari, tenor; Mondo–Walter Testolin, basso. Ensemble vocale e strumentale–I Musici di Santa Pelagia; Maurizio Fornero, director.

He had gone away light-hearted after the first lesson, with music in his heart and ears. Was not every beginning of new love a spring that promised summer, and sometimes a rich autumn too, all in a few weeks, and with only a dull day or two to follow at the end, instead of winter?

But the next time he saw Ortensia it was a little different, and after that the difference became greater, and at last very great indeed, till he no longer recognised the familiar turnings in light love’s short path, and the pretty flowers he had so often plucked by the way did not grow on each side within easy reach, and the fruit of the garden seemed endlessly far away, though he knew it was hidden somewhere, far sweeter than any he had tasted yet. For it was a maiden’s garden in which no man had trod before; and the maiden was of high degree, and could not wander along the path with him, yielding her will to his.

His light-heartedness left him then, his face grew grave, and his temper became melancholy, for the first time in his life. He was only to give her a few lessons, after all, and Pina would leave him with her for ten minutes, scarcely more, each time he came. One minute would be enough, it was true; if he spoke she would listen, if he took her hand she would let him hold it. But what would be the end of that? A kiss or two, and nothing more. When the lessons were finished he would be told by the Senator that his teaching was no longer needed, and after that there would be nothing. He might see her once a week in her gondola, at a little distance; but as for ever being alone with her again in his life for five minutes, that would be out of the question. Could he, a musician and an artist, a man sprung from the people, even think of aspiring to the hand of a Venetian senator’s niece? In those days the idea was ludicrous. And as for her, though she might be in love with him-and he felt that she was-would she entertain for a moment the idea of escaping from her uncle’s house, from Venice, to join her lot with a wandering singer’s? That was still greater nonsense, he thought. Then what could come of it all but a cruel parting and a heartache, since this was real love and could not end in a laugh, like the lighter sort he had known so well? She was a mere child yet, she would forget in a few weeks; and he was a grown man, who had seen the world, and could doubtless forget if he chose, provided there were never anything to be forgotten beyond what there was already.

But if he should speak to her in one of those short intervals when they were alone, if she stretched out her hand, if he clasped her to him, if their lips met, things would not end so easily nor be so soon forgotten. He had the careless knowledge of himself that many gifted men have even when they are still very young; he knew how far he could answer for his own coolness and sense, and that if he allowed himself to cross the limit he would behave like a madman and perhaps like a criminal.

Therefore he set himself to be prudent till the lessons should be over, and he even thought of ending them abruptly and leaving Venice. His acquaintance with Ortensia would always be a beautiful recollection in his life, he thought, and one in which there could be no element of remorse or bitterness. He was not a libertine. Few great artists have ever been that; for in every great painter, or sculptor, or musician there is a poet, and true poetry is the refutation of vulgar materialism. In all the nobler arts the second-rate men have invariably been the sensualists; but the masters, even in their love affairs, have always hankered after an ideal, and have sometimes found it.

When the Senator ushered in Stradella one morning and quietly announced that the lesson was to be the last, Ortensia felt faint, and turned her back quite to the open window, against the light, so that the two men could not see how she changed colour. The nurse’s hard grey eyes scrutinised Pignaver’s face for an instant, and then turned to Stradella; he was paler than usual, but grave and collected, for the Senator had already informed him that his services would be no longer needed after that day.

Everything was to take place as usual. As usual, Ortensia was to sing one of her uncle’s ninety-seven compositions to him while Stradella accompanied her; as usual, Pignaver would then go away; lastly, at the customary time, Pina would go out for ten minutes and reappear with water and sherbet.

Ortensia was shaking with emotion when the ordeal began, and for a moment she felt that it was hopeless to try to sing. Some sharp discordant sound would surely break from her lips, and she would faint outright in her misery.

Stradella, Sinfonia XXII as performed by Italy’s newest Baroque ensemble, Il Caleidoscopio (Baroque violin: Lathika Vithanage; Viola da gamba: Noelia Reverte Reche; Baroque harp: Flora Papadopoulos)

She was on the very point of saying that she felt a sudden hoarseness, or was taken ill, when her pride awoke in a flash with a strength that amazed her, the more because she had never dreamed she had any of that sort. Stradella should not guess that she was hurt; she would rather die than let him know that her heart was breaking; more than that, she would break his, if there was time, and if she could!

She stood up by her chair and sang far better than she had ever sung before in Pignaver’s hearing; she threw life and fire and passion into his mild composition, and she remembered every effective little trick Stradella had taught her for improving the dull melody and for emphasising the commonplace verses it was meant to adorn.

The Senator was surprised and delighted, and Stradella softly clapped his hands. She hated him for applauding her, yet she was pleased with the applause.

‘What music, eh?’ cried the Senator, with a grin of satisfied vanity.

‘It is music indeed!’ answered Stradella with a grave emphasis that gave the words great weight. ‘It has been my endeavour to do justice to it, in instructing your gifted niece.’

‘You have succeeded very well, dear Maestro,’ Pignaver answered with immense condescension. ‘The world will be much your debtor when it hears my melodies so charmingly sung!’

With this elephantine compliment the Senator nodded in a patronising way and took himself off, while Stradella bowed politely at his departing back.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pkDUpn92DOA

Stradella, Deh, recevi I nostri Voti, performed by Lavinia Bertotti, soprano; Mara Galassi, Baroque harp; Orchestra Barocca della Civica Scuola di Musica di Milano, Enrico Gatti, director.

When the curtain fell before the door, the singer turned to his pupil and sat down in his accustomed seat, with great apparent self-possession. Ortensia watched him, and her new-born resentment increased quickly.

‘What will it please you to study to-day?’ he inquired, just as easily as if it were not the very last time.

She felt much inclined to answer ‘Nothing,’ and to turn her back on him, but somehow her pride found a voice for her, as indifferent as his own, though she avoided his eyes and looked out of the window.

‘It does not matter which song we take,’ she answered. ‘They are very much alike, as you have often said!’ She even laughed, quite lightly and carelessly.

It was his turn to be surprised. Her tone was as natural and unstrained as a child’s. At the sound of it, he asked himself whether this slip of a thing of seventeen years had not been acting emotions she had not felt, and laughing at him while he had been singing his heart out to her. Any clever girl could twist herself on her chair, and lay her cheek to the back of it, turning away as if she were really suffering, and twining her hands together till the little joints strained and turned even whiter than the fingers themselves.

At the thought that she had perhaps made a fool of him, Stradella nearly laughed, and he came near being cured then and there of his latest and most serious love-sickness. His lute was lying on his knees; he began to strum the opening chords of Pignaver’s dullest composition, in the dull mechanical way the music deserved. He thought the effect might be to make Ortensia laugh and to change her mood.

But, to his annoyance, she rose, laid one hand on the back of the chair, and proceeded to sing the song with the greatest care for details, though by no means with the dashing spirit that had made him applaud her first performance that morning. She was evidently singing for study, as if she meant to profit by his teaching to the very last moment.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ol3j6Mheh7o

Stradella, Sinfonia N 17 performed by the Purcell Quartet

He accompanied her mechanically, wondering what was going to happen next, and when she had finished he eyed her with curiosity, but said nothing. She seemed completely changed.

‘Why do you look at me in that way?’ she asked with great calmness. ‘Did I make any bad mistake?’

He smiled, but not very gaily.

‘No,’ he answered, ‘you made no mistakes at all. You are admirable to-day! I quite understand that my services are no longer needed, for I can teach you nothing more!’

‘I have done my best to improve under your instructions,’ answered Ortensia primly.

She rested both her elbows on the back of the chair now and looked calmly out of the window at her favourite tree. Stradella pretended that his lute needed tuning, turned a peg or two and then turned each back again, and struck idle chords.

‘When you are rested,’ he said, ‘I am at your service for another song.’

‘I am ready,’ Ortensia answered with a calmness quite equal to his own.

Pina, watching them from a distance and neglecting her lace-pillow, saw that something was the matter, and got up to leave the room at least half-an-hour earlier than usual; but because the Senator might come back unexpectedly during this last lesson, she went out through the other door beyond which a broad corridor led to his own apartments, and she stood where she could not fail to hear his steps in the distance if he should return.

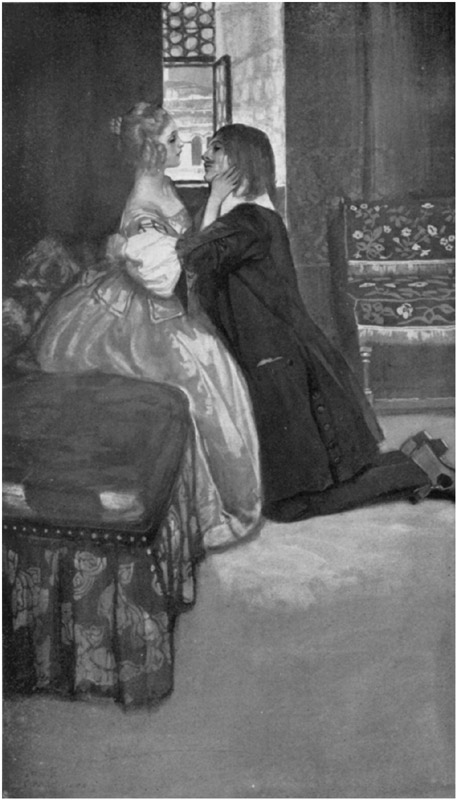

Ortensia was still standing by her chair when Stradella left his seat and came towards her, holding his lute in one hand. It did not suit his male dignity to take leave of her without finding out whether she had been playing with him or not, though half-an-hour earlier he would not have believed it possible that vanity could enter into any thought he had of her.

He stood quite near her, and she met his eyes; she was rather frightened by his sudden advance, and shrank back behind the chair.

‘You will find me in your loggia to-night, outside that window,’ he said, pointing as he spoke. ‘I shall be there an hour before midnight, and I shall wait till it is almost dawn.’

Stradella, Chare Jesu suavissime. Gerard Lesne (contralto) with Il Siminario musicale

He paused, keeping his eyes on hers. She had started back at the first words, and now a deep colour had risen in her cheeks; he could not tell whether it meant anger or pleasure.

‘I shall be there,’ he repeated; ‘I shall be there to say good-bye, if you will have it so, or to come again if you will. But if you do not open the window, I will come twice again at the same hour, to-morrow and the night after that, and wait for you till dawn.’

Ortensia turned from him without speaking and went out into the covered loggia. It was her instinct to look at the place where he was to be, and for the moment she could not answer him, for she did not know what to say; she herself could not have told whether she was angry or pleased, she only felt that something new was happening to her. Her mood had changed again in a few seconds.

He followed her to the threshold of the window, and stood behind her in the flood of sunshine, so near that he could whisper in her ear and be heard.

‘There is love between us,’ he said. ‘We have seen it in each other’s eyes ever since we first met, we have heard it in one another’s voices every day! I will not leave you without saying it for us both, just as much for you as for myself! But I must say it all many times, and I must hear it from you too.

Therefore I shall be here an hour before midnight to wait, and you will come, and you will open the window when you see me standing outside, and we shall be together! And if you will, we need never part again, for the world is as wide as heaven itself, for those who love to find a safe resting-place.’

F. Marion Crawford’s Stradella is free to read and download online at Project Gutenberg.