Dave Brubeck, of whom the author writes: ‘I have long admired and respected Dave Brubeck as a man and as a musician, as a force for change in human relations and as a man deeply committed to the roots of jazz, who nevertheless looked to expand on its root vocabulary by referencing his deep love for and knowledge of traditional and modern western classical music, and he was always looking to introduce polytonal, polyrhythmic and contrapuntal elements into the collective dialog. And for this, at the height of his popular breakthrough, he had to eat a lot of politically correct shit from pseudo-hipster, pseudo-liberal jive artists masquerading as ‘critics’ for having the effrontery to be both white and popular.’

(Ed. Note: As Dave Brubeck’s 90th birthday approached in 2010, contributing editor Chip Stern hailed the achievements of the jazz titan in an in-depth appraisal/defense published in the December 2010 issue of TheBluegrassSpecial.com. One of the most informed perspectives we’ve read on the great Brubeck, who passed away at age 92 on December 5—a day shy of his 93rd birthday—Stern (not only a long-time Brubeck fan, but a musician in his own right and one of the top music writers in the business) came from a place of deep knowledge of Brubeck’s art, and in fact is the author of the liner notes for the initial CD release of The Real Ambassadors, a powerful anti-segregation missive disguised as a jazz operetta written by Brubeck in collaboration with his wife Iola and realized on disc by a Brubeck piano trio with Eugene Wright and Joe Morello; the Louis Armstrong All-Stars; the great vocalist Carmen McRae and the remarkable vocal trio of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. As a corrective to some well-intentioned but ultimately misguided or misinformed posthumous accountings of Brubeck’s career published in the mainstream music press, we revisit Sterns’ insightful piece and would point out in addition that Stern wasn’t sitting around waiting for the great artist to die before properly saluting his achievements.)

The Dave Brubeck Quartet in its second iteration—wherein the great pianist-composer and his alto saxophone doppelganger Paul Desmond were joined by the great bassist Eugene Wright and drummer Joe Morello—was among the most esteemed recording and performing ensembles in the history of jazz, and most of you are undoubtedly familiar with their famous 1959 recording Time Out, which introduced a number of memorable jazz standards in what were then considered rather esoteric time signatures.

Well, on December 6, 2010, Brother Brubeck celebrates his 90th birthday, and as befits a life so righteously and creatively lived, the honors and outpouring of affection promise to prove something of an ongoing Mardi Gras, an outpouring of love and respect for this American original, beginning as it were when the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts announced that Brubeck would be a 2009 Kennedy Center Honoree, and culminating in a documentary about the man, his life and his music—Dave Brubeck: In His Own Sweet Way—produced by a piano-playing admirer of some standing (Clint Eastwood), directed by Bruce Ricker, and premiering on TCM the evening of December 6.

I have long admired and respected Dave Brubeck as a man and as a musician, as a force for justice and tolerance in human relations, and as an artist deeply committed to the roots of jazz, who nevertheless looked to expand upon its root vocabulary by referencing his deep love for and knowledge of western classical music in its traditional and modern iterations—Dave was always looking to introduce polytonal, polyrhythmic and contrapuntal elements into the collective dialog.

And for this, at the height of his popular breakthrough, he had to eat a lot of politically correct shit from pseudo-hipster, pseudo-liberal jive artists masquerading as “critics” for having the effrontery to be both white and popular. He was indiscriminately lumped in and dismissed with progenitors of the so-called cool school and West Coast Jazz, even though there was always a profound stomp and blues flavor to his creations. The one time I had the opportunity to interview this gracious gentleman, I got the distinct impression those jabs and put-downs still rankled him decades later.

Dave Brubeck Quartet, ‘Three To Get Ready’

Still, be that as it may, Brubeck has outlasted most knee-jerk detractors, and remains hard and committed, still out there, still making gigs and turning out superb recordings such as a wonderful solo piano recording he released on the Telarc label in 2004.

Private Brubeck Remembers reprises the music of a generation of very young men who went overseas during World War II, leaving their sweethearts behind; uncertain as to whether or not they would see each other again. It manages to balance ambiguity and nostalgia, throwaway tunes and real classics in a way that is at once quite touching and swinging, without ever indulging in cheap sentiment. Private Brubeck Remembers is a poignant, often joyous recital, with wonderful recorded sonics, animated by the kind of warmth and generosity of spirit we have come to expect from its creator, now entering his eighth decade as a recording-performing icon.

And yet, now and again, while nowhere near as pernicious as the kind of pseudo-liberal condescension he used to endure during his popular ascent, it still seems as though for a few holdouts, Brother Brubeck has yet to prove his mettle, to earn his spurs.

*Never mind that four of his six children (pianist Darius, drummer Dan, trombonist-bassist Chris and cellist Matthew) are excellent musicians in their own right, and often collaborate with their father.

*Never mind that on one hand you can clearly hear the likes of Jelly Roll Morton, Earl “Fatha” Hines, Willie “The Lion” Smith, Fats Waller, Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Milt Buckner echoing about in Brubeck’s deeply informed historical perspective of the American piano.

*Never mind that in an extensive body of work for Fantasy Records (which he helped found), and which precede the more famous band on Columbia Records, which came to be known as his classic quartet, some of his improvisations and experiments in modern music were of a magnitude and vision that you could subsequently trace his influence on the avant gardists such as Cecil Taylor.

*Never mind that countless jazz musicians, including no less an innovator than Miles Davis, have turned to such superlative Brubeck jazz standards as “In Your Own Sweet Way” and “The Duke,” and found something of themselves in their lilting melodies and sophisticated harmonies.

*Never mind that he fronted a fully integrated Army band, that performed all over Europe for a decidedly segregationist American Army, during World War II.

*Never mind that the classic Brubeck Quartet featured a virtuoso African-American bassist, Eugene Wright (who brought a degree of rhythmic and harmonic sophistication that was at once both cutting edge and firmly rooted in the Walter Page/Count Basie rhythmic tradition), nor that Brubeck would routinely turn down lucrative bookings at colleges and performance venues where any semblance of segregation was tolerated.

*Never mind that Dave and his wife Iola Brubeck always championed human rights, never more so than when they wrote and produced a jazz operetta, The Real Ambassadors, for the great Louis Armstrong that was an alternately satirical/heartfelt call for liberation and freedom and humanistic values, coming hot on the heels of Brown V. Board of Education, when Jim Crow America was still lurching its way along in the days before the Civil Rights and Voting Rights legislation of the mid-’60s.

The Real Ambassadors was recorded at Columbia’s acoustically splendid 30th Street Studios in the fall of 1961, and last enjoyed a commercial release on CD in 1994 for the Sony Legacy label (I myself was privileged to speak with Dave and pen the liner notes for this historic album’s initial offering on CD). Besides Louis, it featured a Brubeck piano trio with Eugene Wright and Joe Morello; the Louis Armstrong All-Stars; the great vocalist Carmen McRae and the remarkable vocal trio of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. In part it referenced the hypocrisy of employing American jazz musicians such as Louis Armstrong as goodwill ambassadors, capable of dissipating anti-American student riots on their State Department tours (as Dizzy Gillespie did back in Greece during 1956) while back at home in the land of the free, African-Americans endured legal apartheid.

In fact, Armstrong, ostensibly an affable accommodating soul (leading some morons to characterize him as an Uncle Tom), was so enraged by how the state of Arkansas denied little black children the right to attend public schools with their white contemporaries back in 1957 Little Rock, that he derided then-Governor Orville Faubus as “…an ignorant plowboy” while publically scorching President Eisenhower for his moral turpitude. Subsequent to this historic recording, there was an undocumented performance of The Real Ambassadors at the 1962 Monterey Jazz Festival, but it has yet to enjoy another public performance (although the Hartford-based jazz vocalist Dianne Mower has launched a Real Ambassadors website dedicated to bringing Dave and Iola’s work to Broadway).

From The Real Ambassadors, Louis Armstrong, Lambert, Hendricks & Ross, perform ‘Everybody’s Comin’,’ ‘Cultural Exchange’ and ‘Remember Who You Are.’

I was always particularly taken by the subtle majesty of Brubeck’s arrangements, and how well they suited Mister Armstrong, iconic without undue nostalgia, modern in a manner which recast Pops as an eternally contemporary artist, not some keepsake of a bygone age, and as such Brubeck’s accompaniment with Eugene Wright and Joe Morello is elegant and graceful and accommodating without seeming to goad Louis on in directions he would rather not go; rather they play to his strengths, which are the eternal strengths of jazz, the genre that burst forth from Armstrong’s innovations and persona like some irresistible force of nature. In fact, Armstrong relates to these Brubeck originals as if he’d written them himself—least ways like he lived them, as on “They Say I Look Like God,” where on some lyrics Dave and Iola had originally written with the expectation of a chuckle, Armstrong delved into a back alley of his soul with such intensity that Brubeck observed tears in the older man’s eyes as he sang “They say I look like God, could God be black, my God, if all are made in the image of thee, could thou perchance a zebra be…” With Lambert, Hendricks and Ross tolling away behind Armstrong in some sing-song call and response that at once seems to reference medieval chant and sanctified spirituals, the hairs on the back of my neck stand up every time I re-visit this performance-hear my plea indeed. And for those who thought that Miles Davis and Gil Evans had the last word on Brubeck’s beloved popular standard “The Duke,” listen to how Louis and the great Carmen McRae interact with the Brubeck trio and each other on a joyous “You Swing, Baby,” with a trumpet break by Satchmo that must’ve given Miles the night sweats.

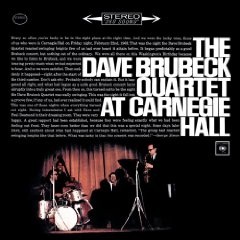

Still, while this 1961 recording features superb aural qualities that complement its superlative arrangements and performances, the CD is inexplicably out of print, although it remains available from select Amazon dealers (often at jacked up collector’s prices) and as an mp3 album download, so keep an ear out for it. In the meantime the Brubeck CD that has been in heaviest rotation as a reference recording every time I am looking to A/B audio gear (or am just down for some swinging musical pleasure), is The Dave Brubeck Quartet at Carnegie Hall (Sony).

In his recollections of this showcase gig from February 22, 1963, Brubeck relates how it occurred smack dab in the middle of a newspaper strike, and the band wasn’t sure anyone would even show up—what’s more, Morello was a bit under the weather. But they ended up playing before a packed house, and from the moment they launched into their opening number, “St. Louis Blues,” it was clear both to the participants on stage and to the audience as a whole, that this was a band on fire. But their fire is informed by the unmistakable grace and relaxation of an ensemble whose skills have been honed over hundreds and hundreds of live gigs and recordings, to the point where they are able to create spontaneous responses and collective orchestrations in the moment that transcend all of their intellectual preparations and conscious decision-making…what drummer Art Blakey once characterized as direct from the creator to the artist to you…that rarefied state where a band looks forward to getting lost, so that they can share the magic of collectively finding their way out of the darkness and back into the light (and vice a versa)-a process of discovery wherein musical comrades share a fresh and unexpected perspectives on familiar terrain.

In his recollections of this showcase gig from February 22, 1963, Brubeck relates how it occurred smack dab in the middle of a newspaper strike, and the band wasn’t sure anyone would even show up—what’s more, Morello was a bit under the weather. But they ended up playing before a packed house, and from the moment they launched into their opening number, “St. Louis Blues,” it was clear both to the participants on stage and to the audience as a whole, that this was a band on fire. But their fire is informed by the unmistakable grace and relaxation of an ensemble whose skills have been honed over hundreds and hundreds of live gigs and recordings, to the point where they are able to create spontaneous responses and collective orchestrations in the moment that transcend all of their intellectual preparations and conscious decision-making…what drummer Art Blakey once characterized as direct from the creator to the artist to you…that rarefied state where a band looks forward to getting lost, so that they can share the magic of collectively finding their way out of the darkness and back into the light (and vice a versa)-a process of discovery wherein musical comrades share a fresh and unexpected perspectives on familiar terrain.

You can feel that vibe on every track and the recorded sound only amplifies the emotional intensity and aw shucks swing with which the band gets in and out of every situation. There is a lovely balance between the stage sound and the hall sound, which to me is particularly powerful on their reading of “Blue Rondo a la Turk” where the band emerges from the jagged formality of the famous 9/8 set-up into a glorious medium-up pulse imbued with a blues feeling, and man is Paul Desmond ever swinging, every melodic phrase browned and burnished in clarified butter and floating demurely over a deliriously laid back Wright/Morello stroll. You can hear Desmond reveling in how the sound of his saxophone comes back to him from the hall, and in a sense the ambience of the hall is dictating his tempo; you can hear the enormity of that sound as it projects into the farthest tiers of the hall, and over a couple of choruses the saxophonist gradually breaks into purer and purer vocal exhortations, as he toys with recollections of an old popular song whose melodic outlines I recognize but whose title I cannot for the life of me call up; still I can clearly apprehend the lyrics (and so can Brubeck, giving Paul an audible amen) as Desmond stretches the words like taffy and seems to intone “…on olllllllllddddddd Broaddddddddwaaaaaaay…” before tying things up with a surprisingly down home testimony. Brubeck then digs deeper into the groove, beginning with big two-handed chords, then down-shifting into teasing single-note blues phrases, introducing subtle little polytonal touches as Wright and Morello settle into an elemental shuffle (and you can clearly dig the palpable weight of Wright’s acoustic bass, the sparkle and presence of Morello’s top cymbal and snare as they move air). As Brubeck begins to double up rhythmically in a powerful evocation of his stride roots, Wright and Morello echo his emotional and physical complexity, bringing things to a dynamic catharsis.

Dave Brubeck Quartet, ‘Blue Rondo à la Turk,’ performance on The Lively Ones TV show (1962)

It is a conclusive moment, but the band rewards the audience with a very loosey-goosey, near eastern-flavored coda on “Take Five,” and as on the band’s other readings of the Time Out and Time Further Out repertoire (such as an utterly charming version of “Three To Get Ready” which leads into the first intermission), their interpretation of this material has grown far less formal and self-conscious, altogether warmer and more confidently swinging, and the manner in which the recording captures Morello’s melodic cross-rhythms and accents on the toms is just remarkable (as is the drummer’s wide-ranging series of rhythmic events on his feature showcase, “Castilian Drums”).

Rarely have rhythm instruments been portrayed with such presence and warmth (dig Wright’s bass on his “King for a Day” feature), nor has a live recording maintained a better, more natural balance between piano and drums (though good microphone work notwithstanding, clearly much of that balance derives from Brubeck’s and Morello’s hands and ears). But with the passing of time, I find myself returning more and more to the band’s elemental workout on “Pennies From Heaven,” a lovely illustration of the band’s deep grounding in and love for the Ellington/Basie lexicon, and where the levels of interplay and swing are damn near telepathic-four men swinging and singing as one. I particularly love the way Brubeck deconstructs and abstracts the theme, like a cat toying with a mouse, before teasing Morello into some syncopated give and take with those joyous, resounding, big band chordal flourishes Dave so fancies.

In listening to this track it occurred to me that in the history of jazz there have been few artists who less deserved to be pilloried with the pejorative “white boy” than Dave Brubeck. Yes, yes, yes, we are all aware of the western Classical and 20th Century devices Brubeck loves to deploy in his music, but on track after track from this concert it is patently clear that Brubeck’s connection to the African-American tradition—not only the big band and stride schools but the most sanctified elements of the church and down home blues—is deep and reverential. (When was the last time you saw that in a Dave Brubeck review?) And as they take the theme out, Brubeck and Desmond engage in a bit of elegant contrapuntal whimsy before settling in on a “…shoot the ticket to my John Boy” closing straight out of the Basie/Jo Jones Reader. Damn…now that’s jazz—one of the greatest concert recordings ever, by one of America’s most remarkable bands.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet, ‘Take Five,’ 1961: Dave Brubeck, Paul Desmond (sax), Joe Morello (drums) and Gene Wright (bass)

If ever there were a stocking stuffer for all seasons, it is The Dave Brubeck Quartet at Carnegie Hall. Rarely has a concert recording made such sense of a venue or the shared feelings of inspiration, let alone make the give and take between band and audience seem more palpable and in the moment.

In fact, even as you’re reaching for your credit cards, Dave is still married to Iola; they still live in their bucolic Connecticut home of 48 years, and he remains restlessly creative, unwilling to function as a human jukebox, with endless re-plays of yesterday’s triumphs. That’s because Dave Brubeck remains humbled both by his gifts and his aspirations, and there yet remains in him a youthful vitality and yearning to explore forms he has yet to master. As such, he lives his life with a sense of joy and discovery and expectation, and while he is no longer the inveterate globetrotter of his youth, he continues to make gigs around the United States, and to pursue his ambitions as a composer. Not the least of which is Sacred Choral Works: Songs of Praise featuring the Pacific Mozart Ensemble and the Quartet San Francisco under the direction of Lynne Morrow and Richard Grant, which was released in January of 2010 on the Dorian Label.

And not to be outdone, at the beginning of November, Sony Classical, culling through the triumphs of his old Columbia recordings, has assembled two wonderful five-CD compilations—Original Album Classics—which by dispensing with the jewel cases and reproducing the original LP artwork as individual CD, offers new and old fans alike a superb introduction to the classic Brubeck oeuvre for the come-and-get-it budget price of $29.95.

There’s The Dave Brubeck Quartet, which is comprised of his great “Time Cycle” of classic quartet recitals: Time Out (1959), Time Further Out (1961), Countdown: Time In Outer Space (1962), Time Changes (1964) and Time In (1966).

‘Castilian Blues,’ from Countdown Time in Outer Space, The Dave Brubeck Quartet

In addition, Dave Brubeck offers Brubeck Plays Brubeck (1956), Dave’s first solo piano recital and his most famous live gig, Jazz Goes to College (1954). Also, there are three more group recitals with the classic Brubeck-Desmond-Wright-Morello juggernaut, including Gone with the Wind (1959), Brandenburg Gate: Revisited (1963) and Jazz Impressions of New York (1965).

Even for so seasoned a boatman as I, some big ones are liable to slip through our fishing nets, and for me, it was a treat to have all the Time Cycle recitals in one set, Countdown: Time In Outer Space being a real find, as I can’t recall ever seeing a copy of this gem in my formative record buying years, nor of Time Changes and Time In. The recorded sound on Countdown is particularly vivid, as are the performances: it was a real pleasure to hear the original studio conception of “Castilian Blues” and “Castilian Drums,” as well as a brisk, gutsy romp through “Fast Life.” Elsewhere the pianist brings things to a rousing, blues-drenched conclusion with “Back To Earth” and a blood and guts nod to primordial piano master Earl Hines on “Fatha.”

Dave is grooving so hard on ‘St. Louis Blues’ that his glasses fly off at 4:33. Pilot of Jam Session TV show hosted by Mort Sahl.

Among highlights of the Dave Brubeck box, the Brandenburg set showcases Paul Desmond in all of his Kahlua & Cream splendor on a string orchestra-abetted arrangement of “In Your Own Sweet Way.” Having said that, I think listeners will be particularly drawn to the charms of Jazz Goes to College, as well as the ruminative narrative of Brubeck Plays Brubeck, wherein we experience more intimate, measured performances of Brubeck’s well-travelled jazz standards, such as a truly inviting rendition of “The Duke” that moves from a delicious medium stroll, through a series of stride, contrapuntal and big band vignettes, all of which serve to illuminate the sweet, playful nature of the man and the expansive vocabulary of the musician, who some 54 years later remains a fountainhead of American values for generation upon generation of newly minted listeners.

Stay just as sweet as you are, Father Brubeck, and like Father Time incarnate, may the winter of your life morph into some other