In this classic Paramount western from 1933, the title character is two-fisted frontiersman Brett Dale, played by a young, mustachioed Randolph Scott. Dale gets wind of a plot to kidnap Alice Gaynor (the fetching Verna Hillie), the daughter of wealthy rancher Jim Gaynor (Harry Carey) and after numerous obstacles saves the girl from the villains’ clutches. Chief heavy Clint Beasley is played by Noah Beery Sr., the epitome of double-dyed villainy. In the film’s best scene, long-suffering Mrs. Beasley (Blanche Frederici) begs Clint not to go through with his lust-inspired abduction of Alice, reminding him “We’ve been married 20 years,” whereupon Beasley growls “Wall, ya needn’t count the last 19 of ’em!”

Based on Zane Grey’s 1920 novel Man of the Forest (which had been filmed previously in 1921 and 1926), the movie was later re-released as Challenge of the Frontier. Randolph Scott, one of the western movies’ greatest stars, had a long and storied career that embraced both the simple morality tales such as this and, in his later years in the 1950s, seven of the most psychologically complex westerns in movie history as directed by Budd Boetticher, with whom Scott forged a personal and professional friendship as strong as that between John Ford and John Wayne. Four of the Boetticher-directed gems were written by Burt Kennedy, a Boetticher mainstay in the ’50s, a decade that not coincidentally saw Scott become one of its top ten box-office stars.

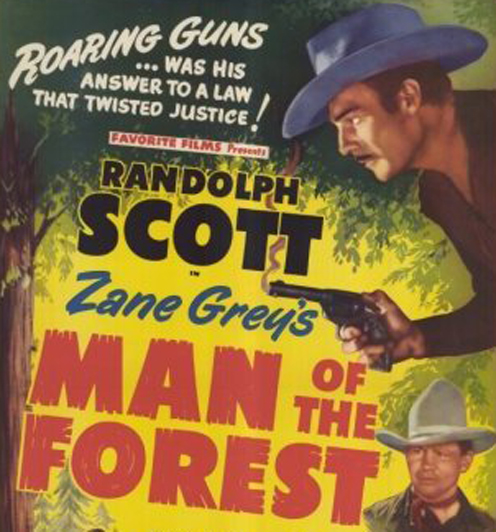

Verna Hellie and Randolph Scott on the Set of Man Of The Forest

In addition to Man of the Forest, Scott had lead roles in four other excellent B westerns, all from the pen of Zane Grey: The Thundering Herd (1933), To the Last Man (1933), Wagon Wheels (1934) and Rocky Mountain Mystery (1935)

In reviewing the evolution of Scott’s screen persona “from generic leading man into the iconic western star he would became through a series of low-budget Paramount Zane Gray adaptations directed by Henry Hathaway,” James Vance of Shadow Cabaret noted:

Of course, movie cowboys had traditionally been solitary figures since the early days of film, a trait that had descended into cliché long before the advent of the talkies. What set the great ones apart from the crowd was the personality each brought to his expected solitude, and how those individual qualities of loneliness, rugged individualism or downright misanthropy informed their screen personas. A scant handful had what it took to achieve stardom beyond the matinee double features, and only three managed to maintain major careers that spanned the ’30s through the ’50s: Scott, Gary Cooper and John Wayne.

Cooper, despite his reputation, brought his well-known reticence and subtle humor to relatively few Westerns; only High Noon tends to be as well remembered as his modern-dress roles. Wayne, the biggest of them all, had tried to pattern himself after the tough but folksy Harry Carey, but as the Duke himself noted, he also “made the Western hero a roughneck” – an aspect that gradually took over until the typical Wayne character had become a brawling lout; the man who’d started out hoping to emulate Carey ended up as a successor to that great screen slob Wallace Beery.

By contrast, Scott came to project an image that was “dignified, democratic, quiet, dependable and at ease with himself”–the words used by Wayne’s biographers to describe Carey. In the early days, Scott’s acting still had some rough edges, and on occasion he could be positively wooden; but as he found his ease before the cameras, he seemed to evolve into an amalgam of the best qualities of Carey and William S. Hart while always remaining essentially himself: a strong, dignified loner with a past that sometimes left him embittered, but never devoid of basic decency. He never could have electrified audiences as Ethan Edwards, anti-hero of The Searchers; cast against type, Wayne’s Edwards was his finest performance…but with Scott in the part it would have been just another of many such complicated men he played over the years.

As the Grey series progressed, Hathaway was allowed to ease off the earlier films’ reliance on stock footage and shoot more new material. In the case of Man of the Forest, the new stuff almost cost the star his life when old film of Jack Holt (from the 1926 version) scuffling with his character’s pet cougar was reshot with Scott and a new cat who turned out to have a taste for horse meat…which was just what Scott reeked of after shooting scenes in the saddle. Though bitten and clawed, he managed to avoid serious injury and filming continued without further incident.

Henry Hathaway went on to forge a significant directorial career, steering Call Northside 777, How the West Was Won (co-directing with John Ford and George Marshall), the original True Grit, The Sons of Katie Elder, North to Alaska, Nevada Smith and Circus World, among others.

Selected Short: Gus Visser and His Singing Duck (1925)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OHd8Hrcj04c

Theodore Willard Case was known for the invention of the Movietone sound-on-film sound film system, a process he began working on in 1921 after his Case Research Lab’s development of the Thallofide (thallium oxysulfide) light-sensitive vacuum tube from 1916 to 1918. The Thallofide tube was originally used by the United States Navy in a top secret infrared signaling system developed at the Case Lab. Case worked with a number of collaborators on a sound-on-film process similar to those in use today. Titles filmed by Case in his process, all made at the Case Studios in Auburn, New York, include Miss Manila Martin and Her Pet Squirrel (1921), Gus Visser and His Singing Duck (1925), Bird in a Cage (1923), Gallagher and Shean (1925), Madame Fifi (1925) and Chinese Variety Performer with a Ukelele (1925). Gus Visser and His Singing Duck was nominated to the National Film Registry in 2002. Nothing much is known about Visser, save that he was a vaudeville performer whose only film appearance seems to have been in the Case sound test reel. How he got the duck to respond on cue remains a mystery. At his death he was residing in North Bergen, NJ.