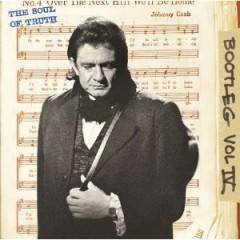

In this the 80th year of Johnny Cash’s birth, Columbia/Legacy is marking the momentous occasion in laudable fashion with five new collections of both vintage and previously unreleased Cash music that pretty much cover the waterfront of the Man in Black’s aesthetic. For this we have to thank Cash, first and foremost, for leaving such a broad and deep catalogue for archivists to mine, and producer Gregg Geller, who has been working in fields of Cash (notably in the House of Cash, site of Johnny’s Hendersonville, TN, recording studio) for years now and admirably shepherding treasure after treasure into the public domain. This past April saw Geller hit a high water mark in his stewardship of the amazing Bootleg Series of rare and previously unissued Cash recordings, with the release of Bootleg IV: The Soul of Truth, a double-disc set annotated by John Carter Cash and featuring three full albums–including one previously unreleased 1975 long player and one long-out-of-print title–of songs of faith along with outtakes from the various gospel sessions. These unearthed gems are stirring in and of themselves and need not be aggrandized beyond that distinction, but in fact they enhance our understanding of Cash by filling in gaps in the catalogue known mostly only to the most hardcore completist fans before Geller rescued them from oblivion.

From The Greatest: The Number Ones, Johnny Cash, ‘Ring of Fire’

Beyond this, an entirely new wrinkle was added to the Cash catalogue in August with the appearance of the first four entries in The Greatest series. The titles are self-explanatory: The Number Ones, Country Classics, Duets, Gospel Songs. These are not about the hidden corners of the Cash oeuvre, but about why he is one of the greatest American artists not merely of his time but in this country’s history. Provocateur, staunch traditionalist, moralist, sentimentalist, patriot, unapologetic witness for his faith and an unapologetic sinner, outspoken defender of the meek and disenfranchised (and, as his daughter Roseanne has said, a mystic too–or so Johnny believed)–it’s as if the entire melting pot character of America was in residence in the corporeal Cash. These qualities (and contradictions) are on ample display throughout the first installment of The Greatest series.

Johnny and June, ‘Far Side Banks of Jordan,’ from Bootleg IV: The Soul of Truth

Of course the question arises as to how much Johnny Cash is too much? Do all of these new Greatest series titles match up to or obviate the need for, say, the great three-CD box set from 2000, with each disc devoted to songs reflecting the tripartite album title Love, God, Murder? Or 2002’s double-disc, 36-song The Essential Johnny Cash? Or 2007’s 24-song Ultimate Gospel overview? Perhaps Gospel Songs is the most redundant of the new releases, but its 14 songs comprise a succinct portrait, gathered over time, of the Man in Black’s spirituality truly unavailable with quite the same focus in any other collection; Country Classics’ 14 tunes from the country canon–the likes of “Old Shep,” “I Forgot More Than You’ll Ever Know,” “The Three Bells,” “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” et al.–are an object lesson in how his identity as a man and as an artist was shaped by the songs of his formative years; being the first of its kind, Duets does not compete with any Cash titles, and the selected tracks–Johnny teaming with not only June Carter Cash but also with his brother Tommy, Waylon, Willie, Dylan, Anita Carter, Ray Charles, George Jones, Lynn Anderson and Billy Joe Shaver–tell us that in his duet choices Cash was more interested in personalizing the performances than in hewing to tradition or merely entertaining the crowd. The underlying theme of Duets, in fact, is friendship, in a classical, not show business sense. Yours truly wrote the liner notes for Duets (and for Gospel Songs, and for Country Classics), and so will now quote himself on the essential truth of this album:

Cash’s well-chosen duets—more male tandems than mixed gender, hearkening back to the brother duets (Monroes, Stanleys, Osbornes, et al.) of roots music’s commercial genesis–betray a deeper purpose on his part. Being a seeker of truth as a gospel singer, so was he affirming the very meaning and value of friendship when he teamed up with another artist.

And that’s not even including the quote from Cicero I got to back this up.

Think ye that Gospel Songs is a catalogue over-reach? Not I. So begin the liner notes:

You are holding an anthology, a small sampling, really, of Johnny Cash’s gospel catalogue, but one illustrating the complete scope of his life as a man of faith. Moreover, the very choice of songs here speaks to the values Cash shared with his fans and from which they leaned together in their earthly trials. …

Thus this collection, in which the texts have both literal and symbolic meaning that was central to shaping the integrity Johnny Cash exuded on and off stage, to affirming the authority his words carried as a man who admitted to falling short of the glory and petitioning the Lord in song for redemption. When coupled to the strength of his faith, Cash’s moral struggles earned him undying affection from his audience which saw in him, and heard in his words, someone who understood them, because he was one of them, as someone who spoke in terms simple, unambiguous and profound in codifying their commonly held values.

Johnny Cash, ‘The Greatest Cowboy of Them All.’ Different recordings of the song are featured on The Greatest: Duets (with Waylon Jennings) and Bootleg IV: The Soul of Truth.

Think ye have heard all there is to hear in a song such as “Wildwood Flower” and “The Three Bells”? Not I:

Far from being commercial juggernauts (though some were, for other artists), these are Country Classics of a different stripe, part and parcel as they are of both Johnny Cash’s and country music’s identity. Be they discourses on sadness, heartbreak, daring, self-affirmation, revenge, heroism, friendship or family, the selections here reveal Cash educating himself in addressing character defining issues in stark, unambiguous terms designed to hit listeners where they live–there was a time, after all, when less jaded Americans would shed tears over the poignancy of Red Foley’s melodramatic boy-and-his-dog saga, “Old Shep,” a tune Elvis Presley liked so much he cut it for his second RCA album in 1956, and which Cash featured on an otherwise sweet-natured, instructive collection of songs he cut specifically for little ones, 1975’s The Johnny Cash Children’s Album. Were our contemporary popular culture less coarse, perhaps Cash’s 1984 single of the Browns’ Grammy nominated 1959 blockbuster “The Three Bells” (adapted from the original, monumental 1956 recording “Les Trois Cloches” by Edith Piaf and Les Compagnons de la Chanson), a poetic examination of a single life’s passages from the cradle to the grave as signified by the tolling of chapel bells, would strike the same humanistic chord an earlier generation responded to in the Browns’ version.

And does one really need to do a selling job for The Number Ones? You know ‘em, they’re part of our common heritage as Americans: “I Walk the Line,” “Ring of Fire,” “Daddy Sang Bass,” “Flesh and Blood,” “(Ghost) Riders in the Sky.” But to sweeten the pot, the must-have Deluxe Edition also includes a DVD of 10 memorable Number Ones performances from the Johnny Cash TV show, including “Ballad of a Teenage Queen”; a rousing, if truncated, workout on “Daddy Sang Bass” with the Carter Family, Statler Brothers and the song’s author, Carl Perkins; the powerful rendition of Kristofferson’s “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down” that has become legendary for Cash’s insistence on keeping the word “stoned” in the song in defiance of ABC executives’ wishes. It goes on. Pretty irresistible stuff and not all of it is on the double-DVD The Best of The Johnny Cash TV Show, 1969-1971, released in 2007. (Much less essential is a new DVD/CD release of a Cash 80th birthday celebration on April 20 at the Moody Theater in Austin, We Walk the Line: A Celebration of the Music of Johnny Cash, with such as Lucinda Williams, Rhett Miller, Iron & Wine, Willie, Shelby Lynne and other in a mixed bag of performances of Cash songs. “Hurt” was an apt choice for Lucinda Williams, since it hurts to sit through her performance; Sheryl Crow is as forgettable on her duet with Willie on “Cry Cry Cry” as she is on his new album, Heroes; on the other hand, Rhett Miller acquits himself well on “Wreck of the Old 97,” and the Carolina Chocolate Drops have a good time with “Jackson.” In short, there are better ways to spend $20 these days.)

Johnny and June, a live version of ‘Over the Next Hill (We’ll Be Home).’ The studio version recorded in 1975 for an album never released is included on Disc 2 of Bootleg IV: The Soul of Truth.

Which brings us to the gem, the Hope Diamond, of this batch of Cash music: Bootleg Vol. IV: The Soul of Truth. Its 51 tracks on two discs include three complete albums: A Believer Sings the Truth, recorded for the Cachet label in 1979, with half of its 20 tracks reissued in 1982 on CBS’s boutique label, Priority Records; Johnny Cash–Gospel Singer, an out of print 1982 album that fell victim to CBS shutting down Priority before the label could release the LP (10 of these cuts finally saw the light of day on the Word gospel label in 1986 as Believe In Him; and not least of all an entire, untitled album recorded in 1975–the finest of the three complete albums in this Bootleg Series title–but never released, for reasons yet unexplained. The remaining tracks are previously unissued outtakes from the abovementioned album sessions.

Which brings us to the gem, the Hope Diamond, of this batch of Cash music: Bootleg Vol. IV: The Soul of Truth. Its 51 tracks on two discs include three complete albums: A Believer Sings the Truth, recorded for the Cachet label in 1979, with half of its 20 tracks reissued in 1982 on CBS’s boutique label, Priority Records; Johnny Cash–Gospel Singer, an out of print 1982 album that fell victim to CBS shutting down Priority before the label could release the LP (10 of these cuts finally saw the light of day on the Word gospel label in 1986 as Believe In Him; and not least of all an entire, untitled album recorded in 1975–the finest of the three complete albums in this Bootleg Series title–but never released, for reasons yet unexplained. The remaining tracks are previously unissued outtakes from the abovementioned album sessions.

Disc 2 contains the untitled, unreleased 1975 album and the Gospel Singer tracks. The former was produced by Charlie Bragg; the latter by Marty Stuart, and listeners will be struck by how these sessions, despite the occasional presence of strings, have an old country church feel, close and intimate in solemn or spirited moments alike. The 1979 cuts comprising Disc 1 have the big Cash concert sound with the band supplemented by horns, strings and multiple backing groups, including the Carter Family (expanded to a quartet with the addition of Jan Howard), the 21st Century Singers septet, the McCormick Brothers trio–in short, the classic Johnny Cash sound from this period.

Johnny Cash, ‘Back in the Fold.’ Written by Marijohn Wilkin, the 1975 studio recording, for an album never released, is included on Bootleg IV: The Soul of Truth.

Marijohn Wilkin’s “Back In the Fold” is the first track on Disc 2, and despite its strings Cash’s deeply committed testimony of redemption and the bluesy punctuations of an electric guitar (multiple players are listed in the credits) nonetheless manage to lend it a confessional tranquility. On the other hand, the piano-driven version of “I Was There When It Happened” comes straight out of the country, and stands in contrast to a version cut in ’79 and featured on Disc 1, with Marshall Grant singing along, whereas the earlier version finds Cash backed by a church choir. The Oak Ridge Boys supply a smooth quartet sound on the thumping “Would You Recognize Jesus” (written by the Statlers’ Don and Harold Reid); and strings, voices, guitar and piano provide a warm backdrop for Cash’s own song anticipating his home-going, the uplifting “Over the Next Hill (We’ll Be Home),” which precedes a stirring duet with June on the similarly themed “Waiting on the Far Side Banks of Jordan,” a song the couple would return to with even greater commitment in their twilight years. Anticipation of eternal life in heaven–a dominant theme of The Soul of Truth–is movingly expressed in the last song on Disc 2, “Never Grow Old,” the vintage gospel standard written by James C. Moore, popularized by the Carter Family and since recorded by some of the giants of country and gospel. With the band subdued and a backwoods piano (sounds like Earle Poole Ball) providing his main support, Cash delivers a beautifully measured vocal, straightforward and heartfelt, abundant in hope.

Hard driving boogie gospel from Johnny Cash on ‘That’s Enough,’ as featured on Bootleg IV: The Soul of Truth

With tunes such as “Gospel Boogie (A Wonderful Time)”, “Children Go Where I Send Thee,” Billy Joe Shaver’s “I’m Just an Old Chunk of Coal,” “You’ll Get Yours and I’ll Get Mine,” and the hard driving boogie of “That’s Enough,” Disc 1 is the more celebratory of the two discs, with Cash indulging in the good news he’s reporting and getting able support from the hot band and spirited backing singers. “I’ve Got Jesus In My Soul” bolsters its message with a swinging touch provided by Dixieland flourishes; the horn-infused gospel stomp of “Strange Things Happening Every Day” gets a jolt of energy midway through via a sizzling rock guitar solo, which surfaces again with searing authority on “That’s Enough”; humor is inherent in the jolly beat and folksy observations of “Strange Things Happening Every Day”; Cash even mates his love of trains to his focus on faith in “This Train is Bound for Glory,” a quintessential Cash thumper partly recited, partly sung, set to a trundling rhythm and enumerating the various miscreants (drunks, adulterers and such) who are unfit to ride “the bible train.” “Didn’t It Rain,” which takes a fanciful view of the Great Flood, pulsates with Praise & Worship energy in the call-and-response between Cash and a female chorus, with another rock guitar solo cutting a hot swath through the arrangement.

At San Quentin, the Johnny Cash troupe performs ‘Daddy Sang Bass.’ Carl Perkins, who wrote the song, contributes a harmony vocal and was the guitarist in Cash’s band at this time. The hit studio version is included on The Greatest: The Number Ones.

On the meditative side, Cash shines on “He Touched Me,” an Elvis favorite (one of King’s most powerful gospel recordings, in fact), here stripped down to a basic band with piano and choir arrangement, simple, direct and moving in its conviction. The album takes it title from (and Disc 1 closes with) a stirring Cash recitation of “Truth,” object of an interesting story Geller relates in his liner notes. Seems Muhammad Ali first presented “Truth” to Cash as a poem, presumably one he himself had written. Cash set it to a sturdy, spare, piano-dominated backing with a female vocalist (sounds like Anita Carter) humming behind his recitation; the words of the poem are alternately mystical and metaphorical. Being familiar with Ali’s style, Geller sensed the truth about “Truth”–that it wasn’t an Ali original. A quick Google search of the first line led him to the website of Hazrat Inayat Khan, an early 20th Century leader of the Universal Sufi movement. With assertions such as “the mind of truth is clear, and stands firm in every storm” and “facts are only in shadow, truth stands above all sin,” it’s easy to see why Cash was drawn to it, as a poet himself and, as per Roseanne’s claim, a mystic as well.

Johnny Cash’s soul was most present on his gospel and spiritual recordings. Lest anyone doubt this, consider the words of his son, John Carter Cash, who–like father, like son–tells it as it is, with a minimum of embroidery: “In all these recordings, one can hear my father’s testimony, and find the fire that drove him on.”

Amen to that, brother, many times over.