Charles Dickens And Music

By James T. Lightwood

Author of Hymn-Tunes and Their Story

(Editor’s note: Continuing the Bicentennial Dickens salute we began in the January issue of www.TheBluegrassSpecial.com, this month we remain focused on our subject’s relationship to music, both as a musician and as an author, as chronicled in James T. Lightwood’s 1912 study of Charles Dickens And Music, originally published in London by Charles H. Kelly. This month, Chapter VI, Songs and Some Singers.)

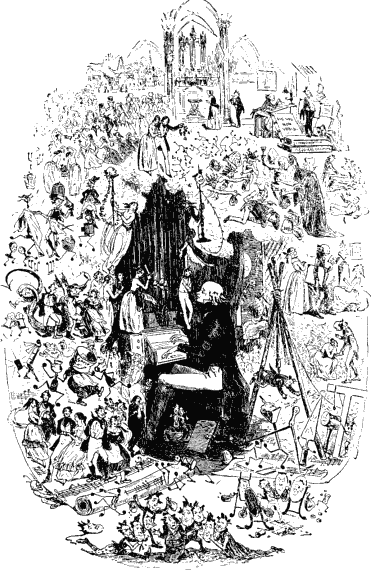

The kind-hearted Tom Pinch, from Dickens’s novel Martin Chuzzlewit, at the organ. ‘The references to the organ are both numerous and interesting, and it is pretty evident that this instrument had a great attraction for Dickens.’

CHAPTER VI

SONGS AND SOME SINGERS

The numerous songs and vocal works referred to by Dickens in his novels and other writings furnish perhaps the most interesting, certainly the most instructive, branch of this subject. His knowledge of song and ballad literature was extraordinary, and he did not fail to make good use of it. Not only are the quotations always well chosen and to the point, but the use of them has greatly added to the interest of such characters as Swiveller, Micawber, Cuttle, and many others, all of whom are of a very musical turn of mind. These songs may be conveniently divided into three classes, the first containing the national and popular airs of the eighteenth century, of which ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘Sally in our Alley’ are notable examples. Many of these are referred to in the following pages, while a full list will be found here www.gutenberg.org.

I. National Songs

There are numerous references to ‘Rule Britannia.’ Besides those mentioned elsewhere we have the picture of little David Copperfield in his dismal home.

What evenings when the candles came, and I was expected to employ myself, but not daring to read an entertaining book, pored over some hard-headed, harder-hearted treatise on arithmetic; when the tables of weights and measures set themselves to tunes as ‘Rule Britannia,’ or ‘Away with Melancholy’!

No wonder he finally went to sleep over them!

In Dombey and Son Old Sol has a wonderful story of the Charming Sally being wrecked in the Baltic, while the crew sang ‘Rule Britannia’ as the ship went down, ‘ending with one awful scream in chorus.’ Walter gives the date of the tragedy as 1749. (The song was written in 1740.)

‘Rule Britannia,’ recorded in 1914 on an Edison cylinder. Vocal by Albert Farrington.

Captain Cuttle had a theory that ‘Rule Britannia,’ ‘which the garden angels sang about so many times over,’ embodied the outlines of the British Constitution. It is perhaps unnecessary to explain that the Captain’s ‘garden angels’ appear in the song as ‘guardian angels.’

Mark Tapley, when in America, entertained a grey-haired black man by whistling this tune with all his might and main. The entry of Martin Chuzzlewit caused him to stop the tune at that point where Britons generally are supposed to declare (when it is whistled) that they never, never, never-

In the article on ‘Wapping Workhouse’ (Uncommercial Traveler) Dickens introduces the first verse of the song in criticizing the workhouse system and its treatment of old people, and in the American Notes he tells us that he left Canada with ‘Rule Britannia’ sounding in his ears.

‘British Grenadiers,’ said Mr. Bucket to Mr. Bagnet, ‘there’s a tune to warm an Englishman up! Could you give us “British Grenadiers,” my fine fellow?’ And the ‘fine fellow,’ who was none other than Bagnet junior (also known as ‘Woolwich’), promptly fetches his fife and performs the stirring melody, during which performance Mr. Bucket, much enlivened, beats time, and never fails to come in sharp with the burden ‘Brit Ish Gra-a-anadeers.’

Our national anthem is frequently referred to. In the description of the public dinner (Sketches by Boz, Scenes 19)-

‘God Save the Queen’ is sung by the professional gentlemen, the unprofessional gentlemen joining in the chorus, and giving the national anthem an effect which the newspapers, with great justice, describe as ‘perfectly electrical.’

On another occasion we are told the company, sang the national anthem with national independence, each one singing it according to his own ideas of time and tune. This is the usual way of singing it at the present day.

In addition to those above mentioned we find references to ‘The Marseillaise’ and ‘Ça ira,’ both of which Dickens says he heard in Paris. In Little Dorrit Mr. Meagles says:

As to Marseilles, we know what Marseilles is. It sent the most insurrectionary tune into the world that was ever composed.

Without disputing the decided opinion expressed by the speaker, there is no doubt that some would give the palm to ‘Ça ira,’ which the novelist refers to in one of his letters. The words of this song were adapted in 1790 to the tune of ‘Carillon National.’ This was a favourite air of Marie Antoinette, and she frequently played it on the harpsichord. After her downfall she heard it as a cry of hatred against herself–it followed her from Versailles to the capital, and she would hear it from her prison and even when going to her death.

In the 1954 film Royal Affairs of Versailles, written and directed by Sacha Guitry, Edith Piaf sings the revolutionary hymn ‘ah! ça ira! ça ira!’ Dickens heard the song while in Paris and referenced it in his novel Little Dorrit, when Mr. Meagles calls it ‘the most insurrectionary tune…that was ever composed.’

When Martin Chuzzlewit and Mark Tapley were on their way to America, one of their fellow travellers was an English gentleman who was strongly suspected of having run away from a bank, with something in his possession belonging to its strong-box besides the key [and who] grew eloquent upon the subject of the rights of man, and hummed the Marseillaise Hymn constantly.

In an article on this tune in the Choir (Nov., 1911) it is stated that it was composed in 1792 at Strasburg, but received its name from the fact that a band of soldiers going from Marseilles to Paris made the new melody their marching tune. A casual note about it appears to be the only musical reference in A Tale of Two Cities.

From America we have ‘Hail Columbia’ and ‘Yankee Doodle.’ In Martin Chuzzlewit we meet the musical coach-driver who played snatches of tunes on the key bugle. A friend of his went to America, and wrote home saying he was always singing ‘Ale Columbia.’ In his American Notes Dickens tells about a Cleveland newspaper which announced that America had ‘whipped England twice, and that soon they would sing “Yankee Doodle” in Hyde Park and “Hail Columbia” in the scarlet courts of Westminster.’

II. Songs from 1780-1840

We then come to a group of songs dating, roughly, from 1780. This includes several popular sea songs by Charles Dibdin and others, some ballad opera airs, the Irish Melodies and other songs by Thomas Moore, and a few sentimental ditties. Following these we have the songs of the early Victorian period, consisting of more sentimental ditties of a somewhat feebler type, with a few comic and nigger minstrel songs. The task of identifying the numerous songs referred to has been interesting, but by no means easy. No one who has not had occasion to refer to them can have any idea of the hundreds, nay, of the thousands, of song-books that were turned out from the various presses under an infinitude of titles during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. There is nothing like them at the present day, and the reasons for their publication have long ceased to exist. It should be explained that the great majority of these books contained the words only, very few of them being furnished with the musical notes. Dickens has made use of considerably over a hundred different songs. In some cases the references are somewhat obscure, but their elucidation is necessary to a proper understanding of the text. An example of this occurs in Chapter IX of Martin Chuzzlewit, where we are told the history of the various names given to the young red-haired boy at Mrs. Todgers’ commercial boarding-house. When the Pecksniffs visited the house

he was generally known among the gentlemen as Bailey Junior, a name bestowed upon him in contradistinction perhaps to Old Bailey, and possibly as involving the recollection of an unfortunate lady of the same name, who perished by her own hand early in life and has been immortalized in a ballad.

The song referred to here is ‘Unfortunate Miss Bailey,’ by George Colman, and sung by Mr. Mathews in the comic opera of Love Laughs at Locksmiths. It tells the story of a maid who hung herself, while her persecutor took to drinking ratafia.

The Kingston Trio performs ‘The Unfortunate Miss Bailey,’ the story of a maid ‘who perished by her own hand early in life,’ as Dickens refers to it in Martin Chuzzlewit.

Dickens often refers to these old song-books, either under real or imaginary names. Captain Cuttle gives ‘Stanfell’s Budget’ as the authority for one of his songs, and this was probably the song-book that formed one of the ornaments which he placed in the room he was preparing for Florence Dombey. Other common titles are the ‘Prentice’s Warbler,’ which Simon Tappertit used, ‘Fairburn’s Comic Songster,’ and the ‘Little Warbler,’ which is mentioned two or three times. Of the songs belonging to this second period, some are embedded in ballad operas and plays, popular enough in their day, but long since forgotten. An example is Mr. Jingle’s quotation when he tells the blushing Rachel that he is going

In hurry, post haste for a licence,

In hurry, ding dong I come back,

though he omitted the last two lines:

For that you shan’t need bid me twice hence,

I’ll be here and there in a crack.

This verse is sung by Lord Grizzle in Fielding’s Tom Thumb, as arranged by Kane O’Hara.

Paul and Virginia is mentioned by Mrs. Flora Finching (Little Dorrit) as being one of the things that ought to have been returned to Arthur Clennam when their engagement was broken off. This was a ballad opera by Reeve and Mazzinghi, and the opening number is the popular duet ‘See from ocean rising,’ concerning which there is a humorous passage in ‘The Steam Excursion’ (Sketches by Boz), where it is sung by one of the Miss Tauntons and Captain Helves. The last-named, ‘after a great deal of preparatory crowing and humming,’ began

in that grunting tone in which a man gets down, heaven knows where, without the remotest chance of ever getting up again. This in private circles is frequently designated a ‘bass voice.’

Dickens is not quite correct in this description, as the part of Paul was created by Incledon, the celebrated tenor, but there are still to be found basses who insist on singing tenor when they think that part wants their assistance.

III. Contemporary Comic Songs

When Dickens visited Vauxhall (Sketches by Boz, Scenes. 14) in 1836, he heard a variety entertainment, to which some reference has already been made. Amongst the performers was a comic singer who bore the name of one of the English counties, and who sang a very good song about the seven ages, the first half hour of which afforded the assembly the purest delight.

The name of this singer was Mr. Bedford, though there was also a Mr. Buckingham in the Vauxhall programmes of those days. There are at least four songs, all of them lengthy, though not to the extent Dickens suggests, which bear on the subject. They are:

1. ‘All the World’s a Stage,’ a popular medley written by Mr. L. Rede, and sung by Mrs. Kelley in the Frolic of the Fairies.

2. ‘Paddy McShane’s Seven Ages,’ sung by Mr. Johnstone at Drury Lane.

3. ‘The Seven Ages,’ as sung by Mr. Fuller (eight very long verses).

4. ‘The Seven Ages of Woman,’ as sung by Mr. Harley.

You’ve heard the seven ages of great Mister Man,

And now Mistress Woman’s I’ll chaunt, if I can.

This was also a very long song, each verse being sung to a different tune.

Some of these songs are found in a scarce book called London Oddities (1822), which also contains ‘Time of Day,’ probably the comic duet referred to in The Mistaken Milliner (Sketches by Boz). This sketch was written in 1835 for Bell’s Life in London, the original title being The Vocal Dressmaker, and contains an account of a concert (real or imaginary) at the White Conduit House. This place of entertainment was situated in Penton Street, Islington, near the top of Pentonville Road, and when Dickens wrote his sketch the place had been in existence nearly a hundred years. Early in the nineteenth century it became a place of varied amusements, from balloon ascents to comic songs. Dickens visited the place about 1835. The titles of some of the pieces he mentions as having been sung there are real, while others (such as ‘Red Ruffian, retire’) appear to be invented.

Of a different kind is the one sung by the giant Pickleson, known in the profession as Rinaldo di Vasco, a character introduced to us by Dr. Marigold.

I gave him sixpence (for he was kept as short as he was long), and he laid it out on two three penn’orths of gin-and-water, which so brisked him up that he sang the favourite comic of ‘Shivery Shakey, ain’t it cold?’

Perhaps in no direction does the taste of the British public change so rapidly and so completely as in their idea of humour as depicted in the comic song, and it is unlikely that what passed for humour sixty years ago would appeal to an audience of the present day. The song here referred to had a great though brief popularity. This is the first verse:

THE MAN THAT COULDN’T GET WARM.

Words by J. Beuler.

Accompaniment by J. Clinton.

All you who’re fond in spite of price

Of pastry, cream and jellies nice

Be cautious how you take an ice

Whenever you’re overwarm.

A merchant who from India came,

And Shiverand Shakey was his name,

A pastrycook’s did once entice

To take a cooling, luscious ice,

The weather, hot enough to kill,

Kept tempting him to eat, until

It gave his corpus such a chill

He never again felt warm.

Shiverand Shakey O, O, O,

Criminy Crikey! Isn’t it cold,

Woo, woo, woo, oo, oo,

Behold the man that couldn’t get warm.

Some people affect to despise a comic song, but there are instances where a good specimen has helped to make history, or has added a popular phrase to our language. An instance of the latter is MacDermott’s ‘Jingo’ song ‘We don’t want to fight but by Jingo if we do.’ An illustration of the former comes from the coal strike of March, 1912, during which period the price of that commodity only once passed the figure it reached in 1875, as we gather from the old song ‘Look at the price of coals.’

We don’t know what’s to be done,

They’re forty-two shillings a ton.

There are two interesting references in a song which Mrs. Jarley’s poet adapted to the purposes of the Waxwork Exhibition, ‘If I’d a donkey as wouldn’t go.’ The first verse of the song is as follows:

If I’d a donkey wot wouldn’t go,

D’ye think I’d wollop him? No, no, no;

But gentle means I’d try, d’ye see,

Because I hate all cruelty.

If all had been like me in fact,

There’d ha’ been no occasion for Martin’s Act

Dumb animals to prevent getting crackt

On the head, for-

If I had a donkey wot wouldn’t go,

I never would wollop him, no, no, no;

I’d give him some hay, and cry gee O,

And come up Neddy.

The singer then meets ‘Bill Burns,’ who, ‘while crying out his greens,’ is ill-treating his donkey. On being interfered with, Bill Burns says,

‘You’re one of these Mr. Martin chaps.’

Then there was a fight, when the ‘New Police’ came up and ‘hiked’ them off before the magistrate. There is a satisfactory ending, and ‘Bill got fin’d.’ Here is a reminder that we are indebted to Mr. Martin, M.P., for initiating the movement which resulted in the ‘Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals’ being established in 1824. Two years previously Parliament had passed what is known as Martin’s Act (1822), which was the first step taken by this or any other country for the protection of animals. In Scene 7 of Sketches by Boz there is a mention of ‘the renowned Mr. Martin, of costermonger notoriety.’ The reference to the New Police Act reminds us that the London police force was remodelled by Mr. (afterwards Sir Robert) Peel in 1829. Hence the date of the song will be within a year or two of this.

Mr. Reginald Wilfer (O.M.F.) owed his nickname to the conventional chorus of some of the comic songs of the period. Being a modest man, he felt unable to live up to the grandeur of his Christian name, so he always signed himself ‘R. Wilfer.’ Hence his neighbours provided him with all sorts of fancy names beginning with R, but his popular name was Rumty, which a ‘gentleman of convivial habits connected with the drug market’ had bestowed upon him, and which was derived from the burden–

Rumty iddity, row dow dow,

Sing toodlely teedlely, bow wow wow.

The third decade of the nineteenth century saw the coming of the Christy Minstrels. One of the earliest of the so-called ‘negro’ impersonators was T.D. Rice, whose song ‘Jim Crow’ (American Notes) took England by storm. It is useless to attempt to account for the remarkable popularity of this and many another favourite, but the fact remains that the song sold by thousands. In this case it may have been due to the extraordinary antics of the singer, for the words certainly do not carry weight (see http://www.gutenberg.org).

Rice made his first appearance at the Surrey Theatre in 1836, when he played in a sketch entitled Bone Squash Diabolo, in which he took the part of ‘Jim Crow.’ The song soon went all over England, and ‘Jim Crow’ hats and pipes were all the rage, while Punch caricatured a statesman who changed his opinions on some question of the day as the political ‘Jim Crow.’ To this class also belongs the song ‘Buffalo Gals’ (see www.gutenberg.org).

The Seven Dials Band, ‘The Ratcatcher’s Daughter.’ The lyrics are by a clergyman, the Rev. E. Bradley, and the song was first performed by the popular singer Sam Cowell. In Out of Season (one of the Reprinted Pieces). Dickens notices the sheet music for ‘The Ratcatcher’s Daughter’ in a music shop ‘having every polka with a coloured frontispiece that ever was published.’

Amongst the contents of the shop window at the watering-place referred to in Out of the Season was every polka with a coloured frontispiece that ever was published; from the original one, where a smooth male or female Pole of high rank are coming at the observer with their arms akimbo, to the ‘Ratcatcher’s Daughter.’

This last piece is of some slight interest from the fact that certain people have claimed that the hymn-tune ‘Belmont’ is derived therefrom. We give the first four lines, and leave our readers to draw their own conclusions. It is worth while stating that the first appearance of the hymn-tune took place soon after the song became popular. (17)

Some Singers

In the Pickwick Papers we have at least three original poems. Wardle’s carol–

I care not for Spring; on his fickle wing

Let the blossoms and buds be borne–

has been set to music, but Dickens always preferred that it should be sung to the tune of ‘Old King Cole,’ though a little ingenuity is required to make it fit in. The ‘wild and beautiful legend,’ Bold Turpin vunce, on Hounslow Heath

His bold mare Bess bestrode-er, with which Sam Weller favoured a small but select company on a memorable occasion appears to have been overlooked by composers until Sir Frederick Bridge set it to excellent music. It will be remembered that Sam intimated that he was not wery much in the habit o’ singin’ without the instrument; but anythin’ for a quiet life, as the man said wen he took the sitivation at the lighthouse.

Sam was certainly more obliging than another member of the company, the ‘mottled-faced’ gentleman, who, when asked to sing, sturdily and somewhat offensively declined to do so. We also find references to other crusty individuals who flatly refuse to exercise their talents, as, for instance, after the accident to the coach which was conveying Nicholas Nickleby and Squeers to Yorkshire. In response to the call for a song to pass the time away, some protest they cannot, others wish they could, others can do nothing without the book, while the ‘very fastidious lady entirely ignored the invitation to give them some little Italian thing out of the last opera.’ A somewhat original plea for refusing to sing when asked is given by the chairman of the musical gathering at the Magpie and Stump (Pickwick Papers). When asked why he won’t enliven the company he replies, ‘I only know one song, and I have sung it already, and it’s a fine of glasses round to sing the same song twice in one night.’ Doubtless he was deeply thankful to Mr. Pickwick for changing the subject. At another gathering of a similar nature, we are told about a man who knew a song of seven verses, but he couldn’t recall them at the moment, so he sang the first verse seven times.

There is no record as to what the comic duets were that Sam Weller and Bob Sawyer sang in the dickey of the coach that was taking the party to Birmingham, and this suggests what a number of singers of all kinds are referred to, though no mention is made of their songs. What was Little Nell’s repertoire? It must have been an extensive one according to the man in the boat (Old Curiosity Shop, 43).

‘You’ve got a very pretty voice’ … said this gentleman … ‘Let me hear a song this minute.’

‘I don’t think I know one, sir,’ returned Nell.

‘You know forty-seven songs,’ said the man, with a gravity which admitted of no altercation on the subject. ‘Forty-seven’s your number.’

And so the poor little maid had to keep her rough companions in good humour all through the night.

Then Tiny Tim had a song about a lost child travelling in the snow; the miner sang a Christmas song–‘it had been a very old song when he was a boy,’ while the man in the lighthouse (Christmas Carol) consoled himself in his solitude with a ‘sturdy’ ditty. What was John Browdie’s north-country song? (Nicholas Nickleby). All we are told is that he took some time to consider the words, in which operation his wife assisted him, and then began to roar a meek sentiment (supposed to be uttered by a gentle swain fast pining away with love and despair) in a voice of thunder.

The Miss Pecksniffs used to come singing into the room, but their songs are unrecorded, as well as those that Florence Dombey used to sing to Paul, to his great delight. What was the song Miss Mills sang to David Copperfield and Dora about the slumbering echoes in the cavern of Memory; as if she was a hundred years old.

When we first meet Mark Tapley he is singing merrily, and there are dozens of others who sing either for their own delight or to please others. Even old Fips, of Austin Friars, the dry-as-dust lawyer, sang songs to the delight of the company gathered round the festive board in Martin Chuzzlewit’s rooms in the Temple. Truly Dickens must have loved music greatly himself to have distributed such a love of it amongst his characters.

It is not to be expected that Sampson Brass would be musical, and we are not surprised when on an occasion already referred to we find him humming in a voice that was anything but musical certain vocal snatches which appeared to have reference to the union between Church and State, inasmuch as they were compounded of the Evening Hymn and ‘God Save the King.’

Thirteen-year-old Julie Andrews sings ‘God Save the King’ at the Royal Variety Performance of 1948

Whatever music he had in him must have been of a sub-conscious nature, for shortly afterwards he affirms that the still small voice is a-singing comic songs within me, and all is happiness and joy.

His sister Sally is not a songster, nor is Quilp, though he quotes ‘Sally in our Alley’ in reference to the former. All we know about his musical attainments is that he occasionally entertained himself with a melodious howl, intended for a song but bearing not the faintest resemblance to any scrap of any piece of music, vocal or instrumental, ever invented by man.

Bass singers, and especially the Basso Profundos, will be glad to know that Dickens pays more attention to them than to the other voices, though it must be acknowledged that the references are of a humorous nature. ‘Bass!’ as the young gentleman in one of the Sketches remarks to his companion about the little man in the chair, ‘bass! I believe you. He can go down lower than any man; so low sometimes that you can’t hear him.’

And so he does. To hear him growling away, gradually lower and lower down, till he can’t get back again, is the most delightful thing in the world.

Of similar calibre is the voice of Captain Helves, already referred to here.

Topper, who had his eye on one of Scrooge’s niece’s sisters (Christmas Carol), could growl away in the bass like a good one, and never swell the large veins in his forehead or get red in the face over it.

Dickens must certainly have had much experience of basses, as he seems to know their habits and eccentricities so thoroughly. In fact it seems to suggest that at some unknown period of his career, hitherto unchronicled by his biographers, he must have been a choirmaster.

He also shows a knowledge of the style of song the basses delighted in at the harmony meetings in which the collegians at the Marshalsea (18) used to indulge. Occasionally a vocal strain more sonorous than the generality informed the listener that some boastful bass was in blue water or the hunting field, or with the reindeer, or on the mountain, or among the heather, but the Marshal of the Marshalsea knew better, and had got him hard and fast.

We are not told what the duet was that Dickens heard at Vauxhall, but the description is certainly vivid enough:

It was a beautiful duet; first the small gentleman asked a question and then the tall lady answered it; then the small gentleman and the tall lady sang together most melodiously; then the small gentleman went through a little piece of vehemence by himself, and got very tenor indeed, in the excitement of his feelings, to which the tall lady responded in a similar manner; then the small gentleman had a shake or two, after which the tall lady had the same, and then they both merged imperceptibly into the original air.

Our author is quite impartial in his distribution of his voices. In P.P. we read of a boy of fourteen who was a tenor (not the fat boy), while the quality of the female voices is usually left to the imagination.

If Mrs. Plornish (Little Dorrit) is to be believed, her father, Mr. John Edward Nandy, was a remarkable singer. He was a poor little reedy piping old gentleman, like a worn-out bird, who had been in what he called the music-binding business.

But Mrs. P. was very proud of her father’s talents, and in response to her invitation, ‘Sing us a song, father,’

Then would he give them Chloe, and if he were in pretty good spirits, Phyllis also–Strephon he had hardly been up to since he went into retirement–and then would Mrs. Plornish declare she did believe there never was such a singer as father, and wipe her eyes.

Old Nandy evidently favoured the eighteenth-century songs, in which the characters here referred to were constantly occurring. At a subsequent period of his history Nandy’s vocal efforts surprised even his daughter.

‘You never heard father in such voice as he is at present,’ said Mrs. Plornish, her own voice quavering, she was so proud and pleased. ‘He gave us Strephon last night, to that degree that Plornish gets up and makes him this speech across the table, “John Edward Nandy,” says Plornish to father, “I never heard you come the warbles as I have heard you come the warbles this night.” Ain’t it gratifying, Mr. Pancks, though; really.’

The Mr. Pancks here referred to did not mind taking his part in a bit of singing. He says, in reference to a ‘Harmony evening’ at the Marshalsea:

‘I am spending the evening with the rest of ’em,’ said Pancks. ‘I’ve been singing. I’ve been taking a part in “White Sand and Grey Sand.” I don’t know anything about it. Never mind. I’ll take part in anything, it’s all the same, if you’re loud enough.’

Here we have a round of considerable antiquity, though the date and author are alike unknown.

Glee-Singing

A feature of the Harmonic Meetings at the ‘Sol’ (Bleak House) was the performance of Little Swills, who, after entertaining the company with comic songs, took the ‘gruff line’ in a concerted piece, and adjured ‘his friends to listen, listen, listen to the wa-ter-fall!’ Little Swills was also an adept at ‘patter and gags.’ Glee and catch singing was a feature at the Christmas party given by Scrooge’s nephew, for ‘they were a musical family, and knew what they were about.’ This remark can scarcely be applied to the Malderton family, who, assisted by the redoubtable Mr. Horatio Sparkins,

tried over glees and trios without number; they having made the pleasing discovery that their voices harmonized beautifully. To be sure, they all sang the first part; and Horatio, in addition to the slight drawback of having no ear, was perfectly innocent of knowing a note of music; still, they passed the time very agreeably.

Glee-singing seems to have been a feature in the social life of Cloisterham (Edwin Drood).

‘We shall miss you, Jasper’ (said Mr. Crisparkle), ‘at the “Alternate Musical Wednesdays” to-night; but no doubt you are best at home. Good-night, God bless you. “Tell me shepherds te-e-ell me: tell me-e-e have you seen (have you seen, have you seen, have you seen) my-y-y Flo-o-ora-a pass this way!”‘

It was a different kind of glee party that left the Blue Boar after the festivities in connexion with Pip’s indentures (Great Expectations).

They were all in excellent spirits on the road home, and sang ‘O Lady Fair,’ Mr. Wopsle taking the bass, and assisting with a tremendously strong voice (in reply to the inquisitive bore who leads that piece of music in a most impertinent manner by wanting to know all about everybody’s private affairs) that he was the man with his white locks flowing, and that he was upon the whole the weakest pilgrim going.

Perhaps the most remarkable glee party that Dickens gives us is the one organized by the male boarders at Mrs. Todgers’, with a view to serenading the two Miss Pecksniffs.

It was very affecting, very. Nothing more dismal could have been desired by the most fastidious taste. The gentleman of a vocal turn was head mute, or chief mourner; Jinkins took the bass, and the rest took anything they could get…. If the two Miss Pecksniffs and Mrs. Todgers had perished by spontaneous combustion, and the serenade had been in honour of their ashes, it would have been impossible to surpass the unutterable despair expressed in that one chorus: ‘Go where glory waits thee.’ It was a requiem, a dirge, a moan, a howl, a wail, a lament, an abstract of everything that is sorrowful and hideous in sound.

The song which the literary boarder had written for the occasion, ‘All hail to the vessel of Pecksniff, the sire,’ is a parody of Scott’s ‘All hail to the chief who in triumph advances,’ from the Lady of the Lake.

Two words that by themselves have a musical meaning are ‘Chaunter’ and ‘Drums’; but the Chaunter referred to is one of Edward Dorrit’s creditors, and the word means ‘not a singer of anthems, but a seller of horses.’ To this profession also Simpson belonged, on whom Mr. Pickwick was ‘chummed’ in the Fleet prison. A ‘drum’ is referred to in the description of the London streets at night in Barnaby Rudge, and signifies a rout or evening party for cards; while one where stakes ran high and much noise accompanied the play was known as a ‘drum major.’

In Our Bore (Reprinted Pieces) this sentence occurs:

He was at the Norwich musical festival when the extraordinary echo, for which science has been wholly unable to account, was heard for the first and last time. He and the bishop heard it at the same moment, and caught each other’s eye.

Dr. A.H. Mann, who knows as much about Norwich and its festivals as any one, is quite unable to throw any light on this mystic remark. There were complaints about the acoustics of the St. Andrew’s Hall many years ago, but there appears to be no historic foundation for Dickens’ reference. It would certainly be interesting to know what suggested the idea to him.

There is a curious incident connected with Uncle Dick, whose great ambition was ‘to beat the drum.’ It was only by a mere chance that his celebrated reference to King Charles’s head got into the story. Dickens originally wrote as follows (in Chapter 14, David Copperfield):

‘Do you recollect the date,’ said Mr. Dick, looking earnestly at me, and taking up his pen to note it down, ‘when the bull got into the china warehouse and did so much mischief?’

In the proof Dickens struck out all the words after ‘when,’ and inserted in their place the following:

‘King Charles the First had his head cut off?’

I said I believed it happened in the year sixteen hundred and forty-nine.

‘Well,’ returned Mr. Dick, scratching his ear with his pen and looking dubiously at me, ‘so the books say, but I don’t see how that can be. Because if it was so long ago, how could the people about him have made that mistake of putting some of the trouble out of his head, after it was taken off, into mine?

The whole of the substituted passage is inserted in the margin at the bottom of the page. Again, when Mr. Dick shows David Copperfield his kite covered with manuscript, David was made to say in the proof: ‘I thought I saw some allusion to the bull again in one or two places.’ Here Dickens has struck through the words, ‘the bull,’ and replaced them with ‘King Charles the First’s head.’

The original reference was to a very popular song of the period called ‘The Bull in the China Shop,’ words by C. Dibdin, Junior, and music by W. Reeve. Produced about 1808, it was popularized by the celebrated clown Grimaldi. The first verse is:

You’ve heard of a frog in an opera hat,

‘Tis a very old tale of a mouse and a rat,

I could sing you another as pleasant, mayhap,

Of a kitten that wore a high caul cap;

But my muse on a far nobler subject shall drop,

Of a bull who got into a china shop,

With his right leg, left leg, upper leg, under leg,

St. Patrick’s day in the morning.

17. Mr. Alfred Payne writes thus: ‘Some time ago an old friend told me that he had heard from a Hertfordshire organist that Dr. W.H. Monk (editor of Hymns Ancient and Modern) adapted “Belmont” from the highly classical melody of which a few bars are given above. Monk showed this gentleman the notes, being the actual arrangement he had made from this once popular song, back in the fifties. This certainly coincides with its appearance in Severn’s Islington Collection, 1854.’–See Hymn-Tunes and their Story, p. 354.

18. The Marshalsea was a debtors’ prison formerly situated in Southwark. It was closed about the middle of the last century, and demolished in 1856.

Next Month: Chapter VII–Some Noted Singers