By Joseph Newsome

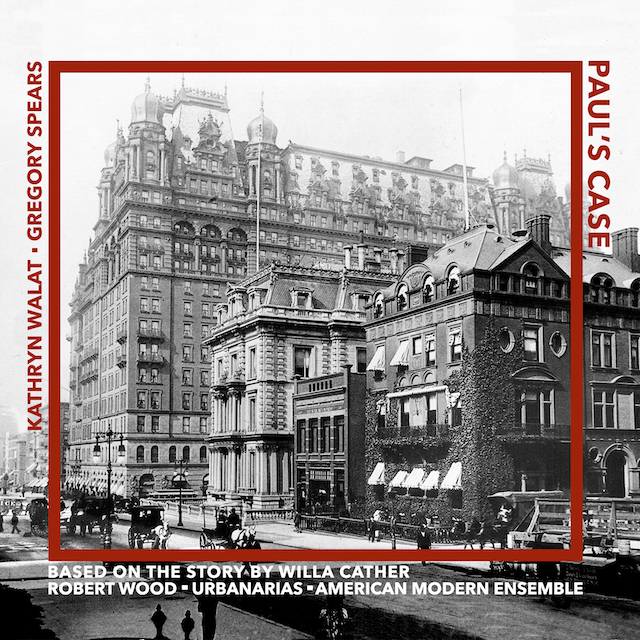

PAUL’S CASE

Gregory Spears (Composer) and Kathryn Walat

Jonathan Blalock (Paul), Keith Phares (Father), Melissa Wimbish (History Teacher, Opera Singer 1, Maid 1), Erin Sanzero (Drawing Teacher, Opera Singer 2, Maid 2), Amanda Crider (English Teacher, Maid 3), Michael Slattery (Yale Boy), James Shaffran (Principal, Bellboy)

American Modern Ensemble; Robert Wood, conductor (Recorded in Performing Arts Center Recital Hall, Purchase College, State University of New York, Purchase, New York, August 6-8 August 2018)

National Sawdust Tracks

Willa Cather

When eminent novelist and Pulitzer Prize-winning chronicler of life on the Nebraska prairie Willa Cather died on 24 April 1947, the America of which she wrote in the iconic works O Pioneers!, The Song of the Lark and My Ántonia was a nation at a crossroads. The optimism of the new century and the Roaring Twenties obliterated by two cataclysmic World Wars and the Great Depression, America in 1947 was a nation in search of renewed identity and purpose, the wounds of past generations still aching beneath new layers of discord and discrimination. Even before the wrath of war and economic collapse upended Cather’s worldview, there were glimpses of darker horizons in her work, their ominous, disquieting hues likely drawn from the recesses of her own temperament. Cather portrayed America as a confederation of microcosms in which the actions of individuals are manifestations of the nation’s spirit.

First published in McClure’s Magazine and subsequently included in the collection entitled The Troll Garden, Cather’s 1905 short story, “Paul’s Case” is to a certain extent a thematic anomaly in her output. Examining the tragic consequences of an imaginative young man’s disenfranchisement with the social and fiscal restraints imposed by the reality of his mundane life, the story inhabits a philosophical world that is very different from the Great Plains pragmatism of the works upon which her reputation is based. From a literary perspective, this deviation from the subject matter with which she was most familiar makes “Paul’s Case” one of Cather’s most significant works.

‘My life caught in the stubble of the world,’ Scene 2d, from Paul’s Case

In this story, the suspicion of the industrialization and urbanization of America typical of her work is turned on its head: rather than a rural outsider gazing into the strange world of the emerging bourgeoisie of manufacturing centers, Paul is a denizen of that world who seeks fulfillment beyond the perceived shortcomings of his own environment. The story’s title suggests a deliberate ambiguity that permeates the story. Scientist and specimen, Paul’s social experiments perhaps reveal more about his own psyche than about the community he spurns. Much of Cather’s writing possesses overtly operatic qualities, but Paul is no conventional operatic protagonist. Morally, socially, and sexually ambivalent, Paul is, as Cather subtitled his “case,” “a study in temperament.”

Gregory Spears

Four years before the triumphant world première of Fellow Travelers, his operatic rumination on same-sex relationships in the hostile milieu of Joseph McCarthy’s America, his quest for inspiring texts led American composer Gregory Spears to “Paul’s Case.” Collaborating with eminent writer Kathryn Walat, author of the critically-acclaimed plays Creation and Bleeding Kansas, he transformed the story’s narrative into a work for the stage in which the nuances of Cather’s subtexts are allied with skillfully-managed motivic writing. Shaped by the rhythms of the words, Spears’s musical language creates an aural atmosphere that, like an anthem that to some hearers celebrates freedom but to other ears symbolizes oppression, is at once both claustrophobic and liberating. There are passages in the score that are reminiscent of the melodic expressivity of Finzi, the stylistic sophistication of Britten, and the harmonic complexity of Tippett, but it is Spears’s singular, unmistakable idiom that creates the piece’s hypnotic sound world. Allied with Walat’s masterful wordsmithing, Spears gives the complicated, in some ways repulsive youth of Cather’s story his own irrepressibly alluring voice.

‘It is his insolence,’ Tribunal Song, Scene 1c, from Paul’s Case

The advocacy of noted champion of contemporary music Robert Wood contributed indelibly to the success of the 2013 première of Paul’s Case by UrbanArias at Artisphere in Arlington, Virginia, and his acquaintance with the score continues to yield tremendous energy and eloquence in this recorded performance. Like vocal works by Philip Glass and Michael Nyman, Paul’s Case needs a conductor capable of facilitating an equilibrium between rhythmic precision and emotive flexibility. The music must be allowed to breathe, simmer, and evolve, but singers’ collective ability to execute their parts with the requisite musical accuracy relies upon a clear, consistent beat. Wood, who also produced the recording, conducts this performance of Paul’s Case with the authority of an artistic steward who has known the score since the ink was still wet. Under his direction, the orchestral forces of American Modern Ensemble rise to the score’s every challenge, playing each note with comprehension of its individual rôle in the opera’s cumulative narrative. The musical foundation of Paul’s Case is a series of understated emotional responses that illustrate the isolation at the opera’s core, intensifying like static electricity until the energy is discharged in climaxes that stun both the characters and the listener. Wood and the American Modern Ensemble musicians handle the opera’s invigorating currents with extraordinary skill and perceptiveness.

It may seem foolish to state that the vocal writing in Paul’s Case is uncommonly singable, but there are far too many instances in which glancing at a few bars of a modern composer’s score reveals ignorance of the science of singing. The voice is a mechanism, but neither a voice nor the singer who operates it is a machine. Physics and physiology govern the production and projection of sound, but the psyche is responsible for giving sounds emotional depth. In this performance of Paul’s Case, tenor Michael Slattery brings an ideal sound to the rôle of the San Francisco-born Yale student who travels to New York City in search of diversion. Spears’s intuitive writing for the part creates a coddled, pied-piper persona that is alternately loathsome and irresistible, and Slattery sings appealingly, every syllable of the text clearly enunciated with the whiff of arrogance expected of an Ivy League man. He perfectly portrays the type of spoiled university student more likely to be found at a fraternity party than in a lecture hall; the type destined to hide his debauched urges and assume his societally-appointed places in a corner office, a smart house in the right part of town, and a seat on a front pew in a smugly respectable church.

‘Draw a bath,’ Quartet, Scene 4c, from Paul’s Case

As the Principal of the school at which Paul struggles, caught between the miseries of peers who do not understand or accept him and teachers who, prejudiced by their own experiences, perhaps understand him too well, baritone James Shaffran personifies the proverbial bureaucratic despot, mundane and inexplicably menacing. Vocally, the part recalls the low-voiced denizens of mythological realms of death and despondency in Seventeenth-Century Italian opera: Shaffran’s Principal articulates Paul’s offenses with the same bemused repugnance with which the Demonio goads the godly hero of Stefano Landi’s Il Sant’Alessio. With his statement of ‘I’m somewhat sympathetic,’ the Principal succinctly asserts the establishment’s noncommittal credo. Duty demands an attempt at compassion, but conventionality prevents any true connection. Shaffran’s vocalism is reliably steady and sonorous, his well-honed technique enabling him to descend to the part’s lowest notes without faking or forcing. Verbally, as the Principal and the hotel bellboy, the baritone’s diction exhibits a clinical coldness that echoes the characters’ disdain and disinterest.

It is not only assigning multiple rôles to several of the singers that makes Paul’s Case an ensemble piece. The various identities assumed by the three female singers are direct descendants of Dante’s Erinyes and the Drei Damen of Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte. Portraying Paul’s teachers, opera singers, and maids at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, where Paul indulges in temporary luxury after fleeing Pittsburgh with the proceeds of his theft, sopranos Erin Sanzero and Melissa Wimbish and mezzo-soprano Amanda Crider sing incisively and, despite the apathy of many of the words that they utter, with palpable involvement in the drama. Sanzero’s performance imparts an unmistakable sense of ennui, the ladies she voices having become indifferent to the social order that mutes their identities. Wimbish wields sensational security in voicing music akin to Jonathan Dove’s writing for the Controller in Flight and the stratospheric lines for Ariel in Thomas Adès’s The Tempest. Crider is vocally and dramatically effective in each of the parts she plays, but her singing of the English teacher’s “Years ago I walked down the aisle with a wayward boy,” distinguished by the simplicity of absolute sincerity, is truly touching.

‘But now the gauntlet has been thrown,’ Paul’s Aria, Scene 3, from Paul’s Case

Intermezzo, Scene 4g, from Paul’s Case

Whilst rehearsing for the still-controversial 1946 NBC broadcast performance of Verdi’s La Traviata, Arturo Toscanini, who had first conducted the score six decades earlier, counseled the young Robert Merrill on the integral rôle played by fatherhood in an effective depiction of the impetuous Alfredo’s father Giorgio Germont. The eminent conductor’s meaning was of course more figurative than literal, but baritone Keith Phares’s performance as Paul’s father in this account of Paul’s Case rekindles the spirit of Toscanini’s observation. His father is the symbolic figurehead of the forces that oppress Paul, but Phares portrays him not as an archetype but as an ordinary man. The strain of attempting to parent an intractable son unnerves Paul’s father, a stereotypical American man of his time for whom nonconformity is not just inconvenient but genuinely dangerous, but Phares discloses the tenderness that prompts the father’s terse treatment of his son. Society alleges that a failed child is also a parent’s failure, and the parent in this performance is acutely cognizant of his own inability to bond with his son. Phares’s vocalism is unfailingly handsome and sagaciously shaded to suit every mood of the text.

Like Monteverdi’s Nerone, Wagner’s Parsifal, Puccini’s Giorgetta, and virtually all of Britten’s operatic protagonists, the title character in Paul’s Case is troubled by a pervasive sense of discomfort with the society in which circumstance places him. He is a dreamer with a hunger for decadence that his blue-collar existence cannot feed. Spears’s and Walat’s characterization of Paul is Freudian in scope, but the music via which the spirited young man makes his ‘case’ necessitates no marvels of penetrating psychological analysis. As sung by tenor Jonathan Blalock, Paul’s music enables the listener to feel the boy’s loneliness, the pain of rejection, and the disappointment and desperation that saturate his flippant words. There is in Paul’s exaggerated politeness a self-delusion that is not unlike Cio-Cio-San’s impassioned insistence that Pinkerton will return to her in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. Blalock’s sweet-toned but iron-willed singing intimates that Paul’s pretentious chivalry is an act of self-preservation.

‘The Red Carnation,’ Aria, Scene 4h, from Paul’s Case

‘But it did not bring him back,’ Ensemble, Scene 5B, from Paul’s Case

Often facing dauntingly high tessitura, the tenor voices Paul’s preternaturally poised music with astounding assurance, glorying in the bel canto essence of Spears’s writing. The interaction between Paul and the Yale student is no typical operatic love duet, but, as Paul’s sole grasp at carnal pleasure, albeit superficial, Blalock approaches the music with an awestruck lover’s ardor. Like the denouement of a Greek tragedy, Paul’s suicide is inevitable. In nature, a thing that cannot survive in its environment is cast out, and Paul’s taste of life, however fleeting, makes returning to a living death impossible. The serene beauty of his singing in the opera’s final minutes is the pinnacle of Blalock’s performance. There are agony and despair in the voice, but the prevailing feeling is one of fulfillment. Death is a culmination, and his gruesome means of achieving it is a neglected boy’s quest for notoriety. Spears and Walat gave Paul a voice: Blalock gives Paul’s voice expressive profundity as moving as that of any character in opera.

Overture: ‘Now I’m lighthearted and free!,’ from Paul’s Case

In the tradition of Sinclair Lewis, Edith Wharton, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and all successful critics of societal injustice and hypocrisy, Willa Cather humanized the communities about which she wrote by populating them with characters who earn readers’ affection and empathy. In “Paul’s Case,” Cather asked readers to embrace an irascible, ill-adjusted boy trapped in his own fantasies. In a sense, opera is a fantastical escape from reality, and Cather’s Paul finds in Gregory Spears’s and Kathryn Walat’s Paul’s Case a refuge from an artless world of tattered textbooks, accounting ledgers, and dead-end jobs. With this marvelous National Sawdust Tracks recording, Paul’s Case finds a home amongst the finest recorded opera performances of the Twenty-First Century.

© by Joseph Newsome, originally published at Voix des Arts.com, 23 October 2019, reprinted with author’s permission.

About the Author: Born in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia in 1978, Joseph Newsome received musical tuition on piano and violin in my youth and advanced to vocal studies at university. Opera and Classical Music are his passions, and he is dedicated to ensuring that, to paraphrase William Faulkner, they do not merely endure but triumph in the 21st Century. Mr. Newsome now resides in Burlington, North Carolina