In the same year his wife died by fire and his only son was almost fatally wounded in the Civil War, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, in deep despair, wrote ‘Christmas Bells,’ a poem in which its author’s doubt of God’s existence is expunged by the message peeling from Yuletide bells. Herewith the true story of the events animating Longfellow’s agonized verses and the text of the complete poem, including two stanzas directly referencing the horrors of the Civil War that were omitted in 1872 when John Baptiste Calkin arranged Longfellow’s verses into the seasonal classic expressing the triumph of good over evil in the world, ‘I Heard The Bells on Christmas Day.’

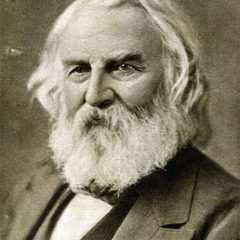

One of America’s best known poets, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882), contributed to the wealth of carols sung each Christmas season when on December 25, 1864, he wrote a seven-stanza poem titled “Christmas Bells.” The poem gave birth to the carol, “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day,” with two stanzas directly referencing the horror of the Civil War omitted and the remaining five slightly rearranged in 1872 by John Baptiste Calkin (1827-1905), who also provided the memorable tune. When Longfellow penned the words to his poem, America was still months away from Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865; his poem reflected the prior years of the war’s despair, while ending with a confident hope of triumphant peace.

One of America’s best known poets, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882), contributed to the wealth of carols sung each Christmas season when on December 25, 1864, he wrote a seven-stanza poem titled “Christmas Bells.” The poem gave birth to the carol, “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day,” with two stanzas directly referencing the horror of the Civil War omitted and the remaining five slightly rearranged in 1872 by John Baptiste Calkin (1827-1905), who also provided the memorable tune. When Longfellow penned the words to his poem, America was still months away from Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865; his poem reflected the prior years of the war’s despair, while ending with a confident hope of triumphant peace.

As with any composition that touches the heart of the hearer, “Christmas Bells” flowed from the experience of Longfellow–involving the tragic death of his wife Fanny and the crippling injury of his son Charles from war wounds. Henry married Frances Appleton on July 13, 1843, and they settled down in the historic Craigie House overlooking the Charles River in Cambridge, Massachusetts. They were blessed with the birth of their first child, Charles, on June 9, 1844, and eventually the Longfellow household numbered five children–Charles, Ernest, Alice, Edith, and Allegra. Alice, the Longfellows’ third child and first daughter, was delivered, while her mother was under the anesthetic influence of ether–the first in North America.

Tragedy struck both the nation and the Longfellow family in 1861. Confederate Gen. Pierre G. T. Beauregard fired the opening salvos of the American Civil War on April 12, and Fanny Longfellow was fatally burned in an accident in the library of Craigie House on July 10. The day before the accident, Fanny Longfellow recorded in her journal: “We are all sighing for the good sea breeze instead of this stifling land one filled with dust. Poor Allegra is very droopy with heat, and Edie has to get her hair in a net to free her neck from the weight.” After trimming some of seven-year-old Edith’s beautiful curls, Fanny decided to preserve the clippings in sealing wax. Melting a bar of sealing wax with a candle, a few drops fell unnoticed upon her dress. The longed for sea breeze gusted through the window, igniting the light material of Fanny’s dress–immediately engulfing her in flames. Attempting to protect Edith and Allegra, Fanny ran to Henry’s study in the next room, where Henry frantically attempted to extinguish the flames with a nearby, but undersized, throw rug. Failing to stop the fire with the rug, he tried to smother the flames by throwing his arms around Frances–severely burning his face, arms, and hands. Fanny Longfellow died the next morning. Too ill from his burns and grief, Henry did not attend her funeral. (Incidentally, the trademark full beard of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow arose from his inability to shave after this tragedy.)

The first Christmas after Fanny’s death, Longfellow wrote, “How inexpressibly sad are all holidays.” A year after the incident, he wrote, “I can make no record of these days. Better leave them wrapped in silence. Perhaps someday God will give me peace.” Longfellow’s journal entry for December 25th 1862 reads: “A merry Christmas’ say the children, but that is no more for me.”

The war continued to cast a grim pallor upon families in the North and the South in 1863. Charles Appleton Longfellow was now 17 and eager to make his mark by joining the military. His father disapproved, but Charles ran away from home and petitioned Captain W.H. McCartney, commanding Battery A of the 1st Massachusetts Artillery to enlist. Captain McCartney, familiar with Charles and his family, wrote to get his permission. By this time, perhaps knowing Charles wouldn’t give in, Henry reluctantly agreed.

Charles Longfellow

Charles turned out to be quite adept as a soldier, and a skilled leader. In fact, when Henry thought he might help his son by seeking the aid of some famous friends, including a U.S. Senator, to secure a commission, he was pleased to learn Charles had earned his commission and advancement on his own merits. Now a Second Lieutenant, Charles saw action at Chancellorsville, Culpepper and several other skirmishes. In November, during the New Hope Church campaign in Virginia, Charles was shot in the left shoulder. The bullet nicked his spine and exited his right shoulder, barely missing paralyzing him. Treated with other wounded at the New Hope Church, Charles eventually was sent back to Washington D.C.

On December 1, Henry received word about Charles and rushed to Washington D.C. and brought Charles back to Cambridge to recover. Only two years removed from the loss of his wife, the loss of his first born son was too much to contemplate. While still grieving for his wife, Longfellow found hope anew in his son’s survival and return home. It was during that time in December 1863, while nursing Charles back to health, that Longfellow penned the poem he titled “Christmas Bells”:

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet

The words repeat

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along

The unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Till, ringing, singing on its way,

The world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime,

A chant sublime

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Then from each black, accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound

The carols drowned

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn

The households born

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head;

“There is no peace on earth,” I said,

“For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good will to men!”

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep;

God is not dead; nor doth he sleep!

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men!

Unable to recover sufficiently to rejoin his unit, Charles was discharged from the Union Army in 1864. For his father, the bells ringing out during the holidays had for two years reminded him only of loss, seeming to him to mock those who had perished. Yet Longfellow, through his son’s survival, did recover hope, and renewed his faith in God despite the destruction and unimaginable toll the war had extracted on both sides. Now he heard the bells peel a different message, a hope to humankind, that one day “The Wrong shall fail/The Right prevail/ With peace on earth, good-will to men!”

‘I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day,’ Johnny Cash

Some ten years after the publication of Longfellow’s poem, some person still unknown recognized Longfellow’s stirring and optimistic interpretation of the Christmas bells as a potential mate mate for an 1872 processional that was strongly reminiscent of the ringing of bells. The tune’s English composer, John Baptiste Calkin (1827-1905), an organist, was the most famous of a family of accomplished English musicians. Initially, Calkin’s melody was published with the 1848 American hymn, “Fling Out the Banner! Let It Float” by George Washington Doane (1799-1859). Ironically, “Fling Out” was an old-fashioned militant missionary hymn that contrasted greatly in purpose and spirit from the more permanent partner of Calkin’s music, “I Heard the Bells.”

Although Calkin’s melody is a beautiful, gentle and lofty rendition of the sounds of Christmas bells and is quite well received during the holidays, at least three alternative tunes have been composed. These are the moderately popular wafting melody by Johnny Marks (1909-1985), who is most noted for “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” and “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree,” plus tunes by John Bishop (ca. 1665-1737) and Alfred Herbert Brewer (1865-1928). Calkin’s melody, however, remains the predominant version sung today.

As a pair, the resonant tones of Calkin’s pensive music, the main component of his reputation, and Longfellow’s evocative poem, comprise a poignant carol. On top of its fine artistry, it offers an undeniable moral whose essence resides in the two phrases at the end of each stanza. “Peace on earth, good-will to men” so appropriately covers both halves of the partly Christmas and partly pacifist carol. No matter how long this particular song endures, may its two laudable themes harmoniously blend together in an everlasting symbiosis for the benefit of humanity.

Sources: What Saith the Scripture?; The Shelf, by J.C. Loophole; William Studwell, The Christmas Carol Reader