Natasha Daly: ‘Getting close to elephants and tigers are at the top of most people’s bucket lists for that country.’

By Duncan Strauss

Many of us who care deeply about the well-being of animals take a dim view of dolphin encounters, those enterprises patronized by tourists on vacation in Hawaii, Florida and other regions with warmer climes. These attractions can be dressed up in ornate duds–at high-end hotels, the swim-with-dolphin outings are often housed in fanciful lagoons encircled by lush landscaping.

But the fundamental flaw remains: Smart, complex, ordinarily wide-roaming animals are held in captivity so that Carl from Des Moines can commune with these sleek creatures (and, sometimes, so Carl’s rambunctious nine-year-old can harass them).

But as problematic as this dolphin scenario routinely can be, it appears to practically merit a cascade of animal welfare kudos compared with what happens when some folks travel to certain international destinations, seeking animal encounters.

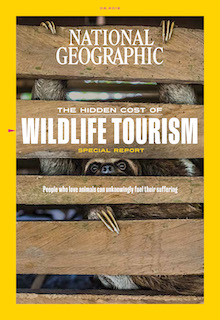

“The wildlife tourism industry in Thailand is a massive part of the economy,” said Natasha Daly, a National Geographic staff writer–she wrote the June cover story, “The Hidden Cost of Wildlife Tourism”–in a Talking Animals interview. “Getting close to elephants and tigers are at the top of most people’s bucket lists for that country.”

We’ll circle back to some of the Thai action in moment, but by the time Daly’s article winds to a close, it manages to project an unusually broad scope. Indeed, Daly, alongside photojournalist Kirsten Luce, traveled the globe, working on this story for a year, documenting the impact ecotourism can have on the fauna when international sightseers want to touch, bathe, sit on or ride exotic animals.

In both the National Geographic piece and the Talking Animals interview, an important theme emerged: the way travelers looking to post selfies and other pictures on their social media feeds have exacerbated the already-harsh conditions for countless animals internationally that are part of the wildlife tourism trade.

Cages, speed-breeding, fear-based training. Blatant animal abuse is hiding just below the surface of the wildlife tourism industry. Hands-on experiences with exotic animals are thriving, boosted by social media. But behind the scenes, animals involved in tourism often lead miserable lives. In this short documentary, National Geographic writer Natasha Daly investigates wildlife tourism in Thailand, where many visitors seek interactions with elephants.

Perhaps the most hair-raising passage in the story–especially for readers who may already be conversant with the horrors befalling elephants, bears and tigers for the cheap entertainment of tourists–deals with beluga whale shows in roving tanks that travel across Russia.

“Yeah, I have to say I had the same reaction when I found out those aquariums exist,” Daly said. “And that was a huge part of the reason we wanted to go to Russia, to document these aquariums. Of course, everyone is familiar with traveling circuses, involving land animals. But these are actually traveling aquatic shows. Belugas and dolphins are put on trucks and brought from city to city, where they will stay for about six weeks, depending on how many tickets are being sold.

“We visited a couple of these shows, and they basically consist of these pop-up inflatable aquariums that are plopped down in the middle of a parking lot of a shopping mall. You go inside and there’s a pool where dolphins and belugas are waiting to perform. People come, and they give a couple of shows a day.

“In talking to marine mammal experts in Russia, it was emphasized over and over that the traveling oceanariums are the most troubling aspect of marine mammal welfare in the country. The sheer size of the pool–it’s much smaller than in a stationary aquarium. And the fact that they’re moving around all the time, experts say that it can be very stressful for these animals. They can be on the road [in the trucks] for a day, sometimes a couple of days. It was absolutely shocking, and it was important for us to actually go and see it for ourselves.”

Apart from beluga whales who hit the road, Jack, Daly’s report painted yet another picture of animals used for entertainment that could cause even the savviest animal advocate’s jaw to drop.

That is, many of us know about dancing bears, bears who ride bicycles, and so on–but how about dancing polar bears? Uh, that definitely seems new. If not downright mind-blowing.

“This is another situation that we also did not know existed until we were in Russia, and people had started telling us that this polar bear traveling circus show existed,” Daly said. “We really wanted to track it down, and find where it was, so we could go document it.

“And we did. We found it in this town called Kazan, Russia. It consisted of a lot of standard circus stuff-performances, acrobatics. But the stars of the show were these polar bears that came out at the end. There were four of them. They all came out on ice. It was a show on ice. Their trainer had a metal rod, and the polar bears were wearing metal muzzles. The trainer would do a trick with one of them at a time. The trick was ballroom dancing or playing an instrument or other things. But what really struck me is that while one polar bear was doing a trick, the other three would be lying down on the ice, rubbing their bodies in it and scratching it up with their nails, and eating it. And it was something that for both Kristen and I, really struck us, because it was visceral contact that this captive polar bear had with this natural ice that they would be living on in the wild.

“I think just watching that is something that really sat with us and was really shocking. The polar bear is this symbol of conservation for so many organizations around the world. To see this entertainment that they were providing in captivity was definitely shocking.”

If it shocks Daly, that’s really saying something: She’s National Geographic‘s Wildlife Crime Reporter, so she’s covered all manner of nefarious commercial activities that involve exploiting or abusing animals. But for this article, Daly also delved into far more commonplace wildlife tourism outings, which still involve a harsh reality for the animals in question. Which brings us back to Thailand. And elephants.

It’s become something of a cliché, for many tourists visiting Thailand, that a must-do entry on their itinerary is going on an elephant ride. Or, maybe taking in an elephant show, which might present the pachyderm performing tricks, like kicking soccer balls, shooting basketballs or throwing darts. Still other elephants specialize in painting pictures.

What those tourists tend to be blissfully unaware of is that it’s not possible for an elephant to safely engage in any of those things, with humans nearby–or aboard!–unless those elephants have been broken.

And that process is every bit as tough and cruel as the word “broken” suggests: Typically yanked away from their mothers as babies, bound by at least their feet, forced into small enclosure, then beaten with sticks or an ankus (also known as a bullhook) for days…until their spirits are broken, they are rendered submissive, and can forever be controlled by their ankus-wielding mahouts, or handlers.

The ‘Phajaan’–Breaking the Spirit of an Elephant: Although elephants are incredibly intelligent and docile by nature, there is very little about the behaviors exhibited by captive elephants in the tourism industry that is natural. To get these wild animals to interact with humans, they must undergo an extraordinarily cruel breaking process, called ‘Phajaan,’ that renders them submissive to their human trainers. Baby elephants are taken from their mothers at a very young age, usually three to six years old, but often younger. After a young elephant is in the captivity of its handlers, the aim of the Phajaan program is to break its spirit.

Sometimes, even after being broken and put to work, there can still be painful moments, not counting strikes or jabs from the ankus. For example, Daly’s reporting included an important section about a young elephant named Meena. Her job was as a painting elephant. Daly noticed that when Meena was shackled around her foot-a common practice with captive elephants–she also had spikes around the shackle. Inquiring about the spikes, Daly was told that Meena had a tendency to kick, and the spikes trained her not to, but was assured that the spikes were removed at night.

An intrepid reporter, Daly returned at night to check that claim, and sure enough: the spikes–which press against Meena’s skin, making it uncomfortable for her to put her foot down–were still on.

“This was an example of something that the average tourist going to watch one of these elephant shows wouldn’t see or notice,” Daly said. “So we really wanted to document the things that tourists, who innocently go to watch these experiences, may not know about the way these animals are kept.”

This represents just another example of how Daly’s article, and Luce’s striking photos, travel notably deep and wide–after they’ve literally done so, with months and months of ambitious globetrotting–to deliver significant information and insights, often about exotic species, and just as often in exotic locales.

They address the basic stuff, too, including a “swim with dolphins” operation in Hawaii (isn’t this where we came in?), and one in Brazil. But not in a basic way. In one passage of the dolphin encounter section, she notes some tourists she interviewed had acknowledged that after seeing the documentary Blackfish, they’d stopped patronizing SeaWorld and other marine parks, now understanding the dark plight of orcas and dolphins living in captivity.

But had no such reluctance to participate in swim with dolphin encounters, which only use captive dolphins. “Yeah, I think what that comes down to,” Daly said, “is that maybe people perceive marine mammal shows as something that’s different from swimming with these animals–swimming with dolphins is still a very popular activity around the world.”

That sound you’re hearing now is countless dolphins–and countless humans who genuinely care about them–sighing.

Follow this link to the edition of Talking Animals featuring the interview with Natasha Daly