I Fagiolini: presenting an eclectic recital evoking not so much the music of Leonardo’s world but the emotional response to his work

By Robert Hugill

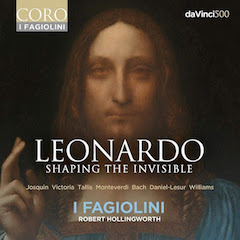

LEONARDO: SHAPING THE INVISIBLE

LEONARDO: SHAPING THE INVISIBLE

I Fagiolini

Coro

How to celebrate Leonardo Da Vinci in music? Leonardo was known to be musical, yet nothing survives and any reconstruction of the “music of his time” would be largely speculative and still say very little about his painting, engineering and scientific studies.

So Martin Kemp (Emeritus Professor in the History of Art at Trinity College, Oxford) and Robert Hollingworth, artistic director of I Fagiolini (the British music ensemble specializing in Renaissance and contemporary music) have put together a recital on Coro that pairs Leonardo’s works of art with music. The musical selection is eclectic, and avoids concentrating on Leonardo’s time with performances from I Fagiolini of music from the 1500s to the present day.

So what we have is Salvator Mundi paired with Thomas Tallis’ and Herbert Howells settings of Salvator Mundi (1575 and 1936 respectively), the Mona Lisa paired with Monteverdi’s madrical Era l’anima mia (1605), St John the Baptist with Jean-Yves Daniel-Lesur’s Le jardin clos from Le cantique des cantiques (1952), The Last Supper with Victoria’s Unus ex discipulis smeis from the Tenebrae Responsories for Maundy Thursday (1583), and Edmund Rubbra’s Amicus Meus from Tenebrae–Second Nocturn (1962), The Musician, Portrait of a Man with a Sheet of Music with Monteverdi’s Tempro la cetra (1619), the drawing of five grotesques with Orazio Vecchi’s Daspuo che stabilao from L’amfiparnaso (1597), the ‘Vitruvian Man’ drawing with Bach’s first Contrapunctus from The Art of Fugue (c1740-50), Ruben’s copy of Leonardo’s The Battle of Anghiari with Janequin’s La guerre (1528), a knot design with Josquin’s Agnus Dei from Missa L’Homme Arme sexti toni, The Annunciation with Victoria’s Alma Redemptoris Mater, the drawing La Scapigliata with Cipriano de Rore’s Or che’l ciel e la terra, and finally a new commission in Adrian Williams’ Shaping the invisible, which examines his obsession with flight.

‘Music cannot be regarded other than as the sister of painting,’ said Leonardo, so for the 500th anniversary of his death in 2019, I Fagiolini and Martin Kemp offer reflections of his images in vocal music: aural fantasia dei vinci–art through the prism of music, in works by Tallis, Victoria, Monteverdi, Bach, Howells and Daniel-Lesur. Robert Hollingsworth, musical director of I Fagiolini, introduces the new album, Leonardo: Shaping the Invisible, explaining: ‘You end up looking at the art through the prism of the music, and vice versa.’

The forces used are diverse from a consort of four singers to full choir. For Monteverdi’s Tempro la cetra tenor Matthew Long sings solo with an instrumental ensemble, and for the Bach fugue the four singers go into real Swingle Singers mode. Some of the choices are left-field: Jean-Yves Daniel-Lesur’s setting of a passage from the Song of Songs for Leonardo’s St John the Baptist, the combination of the erotic with the religious in the Song of Songs intended to echo the same odd mixture in the rather knowing and sexy figure in the painting.

This eclectic mix gives a hint of the diversity that exists in Leonardo’s interests, something which is frankly difficult to capture nowadays as so much has been lost so that our view of Leonardo is somewhat lopsided (fantasies about flight, but very little of his real engineering; none of his music at all, though he may have been employed as a musician).

Now, I have to be frank and admit that when I listen to music, I don’t see images and my mind rarely conjures up visual comparisons for the music. This disc is perhaps best listened to in tandem with the website (https://www.ifagiolini.com/leonardo), where you can see large scale reproductions of the images and see how the music evokes them for you.

From Leonardo: Shaping the Invisible, ‘Salvator Mundi’ paired with Thomas Tallis’ and Herbert Howells settings of ‘Salvator Mundi’ (1575 and 1936 respectively), by I Fagiolini. Geek point: the Tallis is heard here at the written pitch given in the 1575 print, and not the transposed up version suitable for modern SATB choirs. Even more interesting than the pitch is the voicing this produces: high voice, tenor, tenor, baritone, bass, allowing the part-writing in the middle voices to be better heard.

I enjoyed the recital for its sheer eclecticism, starting with Tallis and Howells setting the same text, Daniel-Lesur between Monteverdi and Victoria, and it is lovely to have some Rubbra too. Janequin’s La guerre has added sound effects which rather than being cheesy, rather serve to heighten the remarkableness of the music. Leonardo would almost certainly have known Josquin Desprez in Milan, so the inclusion of the Agnus Dei from his Missa l’Homme Arme sexti toni is a fascinating point of contact between fact and fantasy (and it is a terrific piece of music).

The new commission Adrian Williams’ Shaping the Invisible, which sets a poem by Gillian Clarke, is a striking and rather effective piece written using a variety of techniques, yet I am not sure it evokes Leonardo’s obsession with flight for me.

Perhaps that is my failing.

The disc is beautifully performed, with very different sense for the various different styles of music. The one to a part consort performances are finely done, with a real sense of intimacy between the voices, and Matthew Long’s solo account of the Monteverdi was also one of the notable things on the disc.

In fact, the recital is full of good things, and can be seen either as a remarkable attempt to explore the different emotional atmospheres of Leonardo’s work, or perhaps simply an enjoyably eclectic recital.

Reprinted courtesy Robert Hugill from Planet Hugill, posted on 25 June 2019