Seven Stanzas at Easter

By John Updike

Make no mistake: if he rose at all

It was as His body;

If the cell’s dissolution did not reverse, the molecule reknit,

The amino acids rekindle,

The Church will fall.

It was not as the flowers,

Each soft spring recurrent;

It was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled eyes of the

Eleven apostles;

It was as His flesh; ours.

The same hinged thumbs and toes

The same valved heart

That—pierced—died, withered, paused, and then regathered

Out of enduring Might

New strength to enclose.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence,

Making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the faded

Credulity of earlier ages:

Let us walk through the door.

The stone is rolled back, not papier-mache,

Not a stone in a story,

But the vast rock of materiality that in the slow grinding of

Time will eclipse for each of us

The wide light of day.

And if we have an angel at the tomb,

Make it a real angel,

Weighty with Max Planck’s quanta, vivid with hair, opaque in

The dawn light, robed in real linen

Spun on a definite loom.

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,

For our own convenience, our own sense of beauty,

Lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour, we are embarrassed

By the miracle,

And crushed by remonstrance.

***

Did Updike Sell the Resurrection Short?

By Mathew Sitman

“Let us not mock God with metaphor,” John Updike wrote in his poem “Seven Stanzas at Easter,” imploring his readers not to believe the resurrection of Jesus could be understood as a mere symbol of uplift and optimism. Retreating to the language of analogy or transcendence just wouldn’t do. Christ’s Passion was not just a parable. If Jesus rose at all, it was “as His body,” an affair not just of the spirit but the flesh. In Updike’s gritty imagery, if Jesus’ cells did not reverse their dissolution, his molecules reknit, his amino acids rekindle, then the Church would fall. Or rather, it shouldn’t have existed in the first place. A Jesus who didn’t walk out of a tomb wasn’t worth worshipping.

The poem gains new life of its own every year around this time. It inevitably flits across social media as Holy Week draws to a close, a very quotable addition to the Facebook feeds of America’s more literary Christians. Updike’s words circulate in more traditional ways, too, giving pastors and priests just the rhetorical flourish they need for their Easter homilies. This Sunday, many churchgoers who’ve never read a page of Rabbit, Run will nod along at Updike’s verse.

The force of “Seven Stanzas,” however, goes beyond its seasonal affiliation. After all, there are others poems about Easter. Perhaps Updike’s resonates because it seems attuned to the nature of belief in the modern world—or rather, it asks the modern believer what she is willing to believe. The poem forces the reader to answer for herself what really happened in that backwater of the Roman Empire in the days after Jesus was executed as a criminal. There can be, to use Updike’s word, no “sidestepping” this issue. Are you “embarrassed” by this “miracle” or not?

This is a perennial question, the place where all quests for the historical Jesus give way to faith—or not—and Updike is not wrong to remind us of its stakes. But for all his theological sophistication, and despite my admiration for his literary gifts, Updike’s poem leaves me unsatisfied. It achieves its existential urgency by skirting the complexity and strangeness of what the Gospels actually tell us about the resurrection. The poem is a blunt instrument, jarring and powerful, but it obscures as much as it reveals.

Continue reading in The Daily Beast…

***

‘Seven Stanzas at Easter’: Some Thoughts

published at The Hebert (undated)

Here’s what I love about Updike’s poem:

- It gives the appropriate importance to the resurrection.

- It speaks our language.

When I say that it gives the appropriate importance to the resurrection, I mean that Updike sees this event as the central event in the Christian faith, with out, “the Church will fall.”

This has been my constant refrain against those who attempt to use science to assail Christianity. Most jump to Genesis 1 and 2 and attempt to refute the creation stories with evidence of a 14 billion-year-old universe. I heartily agree with them and say: “Yes, I too think the universe is that old. Let’s also talk about the 4.5 billion-year-old Earth!” If the story of Adam and Eve or either of the creation stories in the Hebrew Bible are shown to be ahistorical, the Church will not fail. These stories are interesting, but they aren’t the heart of the faith. The heart of Christianity is found in Christ and more specifically in his resurrection. Consider this: Jesus dies as the vast majority of his disciples have abandoned him. The resurrection is that event which brings them back together, galvanizes them, and reinvigorates them for the life of persecution that they will lead in the wake of the scandal.

For the Christian, the resurrection is the ballgame; it’s everything.

Second, I love that the poem speaks our language. It mixes in the language of quantum physics, biology, and medicine. Updike doesn’t ask us to shy away from the scientific implications of the resurrection; instead, he asks us to consider them part of the miracle. The resurrection is real, down to the amino acids involved and the existence of the angel in our dimension.

This is good stuff. Thank you, Mr. Updike. May you rest in peace!

***

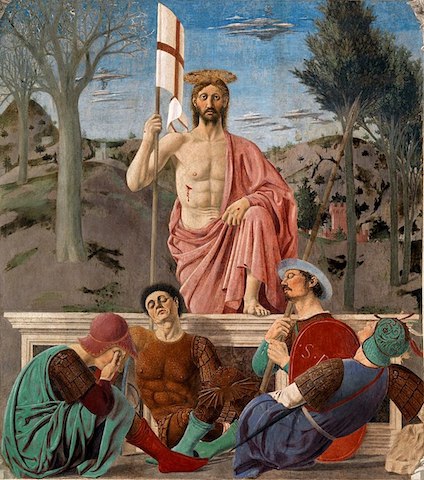

‘The Resurrection,’ by Piero della Francesca in the 1460s

A Few Minutes with ‘Seven Stanzas at Easter’

by Tom Grosh IV

Published 21 April 2011 at Emerging Scholars blog

While reading Kent Annan‘s After Shock: Searching for Honest Faith When Your World Is Shaken (InterVarsity Press. 2011), I came across selections from John Updike’s “Seven Stanzas at Easter.” On Easter, as he wrestles with faith in the face of “scientific modernity’s assault on faith in the resurrection,” Kent appreciates reading “Seven Stanzas at Easter”:

I can identify with these doubts, but he [Updike] asserts they shouldn’t embarrass us into unbelief. The stanzas of the poem articulate the kind of faith I need in response to Haiti, where so many died (by comparison, a similar-intensity earthquake in Los Angeles in 1994 killed only seventy-two people) largely because they had been left behind by poverty by the modern world.

I nod Amen with him, as the physical specificity of faith (of the Savior) must respond to the physical, concrete rubble that I drive by in Haiti, as well as the physically decomposed bodies I see even months later being uncovered and put into plastic bags that are thrown into the back of dump trucks:

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence,

Making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the faded

Credulity of earlier ages:

Let us walk through the door.

The stone is rolled back, not papier-mâché ,

Not a stone in a story,

But the vast rock of materiality that in the slow grinding of

Time will eclipse for each of us

The wide light of day.

Walking “through the door” makes sense as a description of faith, more so to me than the famous definition in Hebrews 11: “being sure of what we hope for and certain of what we do not see” (TNIV). — 95 – 96.

What do you think of John Updike’s “Seven Stanzas at Easter” and Annan’s meditation upon it? How do you live in and articulate the reality of the resurrection in the midst of higher education?

***

The Morning of the Resurrection 1886 Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt 1833-1898

John Updike Blows It About the Resurrection

By D.C. Toedt

published at The Questioning Christian

At the otherwise-wonderful Great Vigil of Easter this morning (a.k.a. the sunrise service), our rector quoted from John Updike’s Seven Stanzas at Easter in his sermon:

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall. [Emphasis added; read it all.]

I’ve tried and failed to read these lines, and the rest of the work, as merely a literary device. They’re not. Updike is clearly drawing a line in the sand about what he thinks actually happened on Easter Sunday.

I can’t understand how Updike can be so certain. We simply don’t know what happened on that Sunday so long ago (or could it have been Saturday?).

We can say, with reasonable confidence:

- that some of Jesus’s disciples found an empty tomb where they had expected to find his body;

- that Peter, along with some unknown number of other disciples, later genuinely believed they had encountered their executed Teacher alive and well;

- that some of Jesus’s disciples found an empty tomb where they had expected to find his body;

- that in the years that followed, stories circulated in various early churches, to the effect that Jesus had supposedly appeared to as many as 500 of his followers; and

- that Saul believed he himself had personally encountered the risen Jesus.

That’s pretty much it. We know nothing of what happened in the tomb between Good Friday evening and Easter Sunday morning. It’s a mystery, and likely always will be. Acknowledging this—facing the facts about our limited information—need not detract from our trust in God and our veneration of Jesus.

Barely 48 hours ago, we commemorated Jesus’s extreme faithfulness to God. He, Jesus, deserves better than Updike’s ipse-dixit, false-choice assertions.

***

The Resurrection of Christ, painting by Nöel Coypel, circa 1700

Seven Stanzas And A Stone At Easter

Published at Thinking Christian.net, 20 April 2014

by Tom Gilson

There are some who say that today, Easter, is a celebration of an excess of imagination. John Updike, never short on imagination himself, says no: the Easter reports were about what happened.

Make no mistake: if he rose at all

It was as His body;

If the cell’s dissolution did not reverse, the molecule reknit,

The amino acids rekindle,

The Church will fall.

It was not as the flowers,

Each soft spring recurrent;

It was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled eyes of the

Eleven apostles;

It was as His flesh; ours.

The same hinged thumbs and toes

The same valved heart

That—pierced—died, withered, paused, and then regathered

Out of enduring Might

New strength to enclose.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence,

Making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the faded

Credulity of earlier ages:

Let us walk through the door.

The stone is rolled back, not papier-mache,

Not a stone in a story,

But the vast rock of materiality that in the slow grinding of

Time will eclipse for each of us

The wide light of day.

And if we have an angel at the tomb,

Make it a real angel,

Weighty with Max Planck’s quanta, vivid with hair, opaque in

The dawn light, robed in real linen

Spun on a definite loom.

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,

For our own convenience, our own sense of beauty,

Lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour, we are embarrassed

By the miracle,

And crushed by remonstrance.

It happened this way, or “the Church will fall.” The apostle Paul said the same in 1 Corinthians 15.

Easter is not an act of human invention; it is the world in full color. Updike is correct to insist that the surface event was never “transcendent” in the sense of unreal; yet there is at the same time a transcendence there that cannot be sidestepped, precisely because the event was real.

To follow Christ requires imagination, yes: not fairy-story imagination, but openness to reality beyond what we see on the surface.

Such openness is, sadly, not always evident. The other day I saw where an atheist blogger (who need not be named) had found “contradictions” in the resurrection accounts, including:

- What were the last words of Jesus? Three gospels give three different versions.

- Could Jesus’s followers touch him? John says no; the other gospels say yes.

Actually, John tells us Jesus told Thomas to touch him, but not to cling to him. There’s a more consequential error on display here, though: a black-white requirement that the accounts be exactly the same or else be contradictory. Real people reporting real events tell stories differently even when telling them truly.

To live this way is to be stuck in a sad sort of stone literalism. Atheism in general implies a cold, hard world of stone. Nothing counts in the God-denier’s world but what’s on the surface, reality defined according to a cautiously contained and convenient beauty, the light weightiness of Max Planck’s quanta with the real life embarrassed out of it.

There is a stone in the story of Christ, too: it‘s been rolled away.

***

Andrea di Bartolo (Italian, active 1389-1428). ‘The Resurrection,’ ca. 1390-1410. tempera paint and gold leaf on panel. Walters Art Museum (37.741): Acquired by Henry Walters with the Massarenti Collection, 1902.

The Resurrection, tempera and gold leaf on panel by Andrea di Bartolo (1360-1428), painted between circa 1390 and circa 1410 (late Medieval). The depiction of Christ’s tomb as a cave appears repeatedly in Italian art of the 14th and early 15th centuries. Here, a glimpse into the cave reveals Christ’s marble sarcophagus, now empty. Framed by the shadowy void of the tomb’s entrance, the resurrected Christ, emitting rays of light, emerges triumphantly from the darkness. This scene was the last in a series of five predella panels (paintings on the base of an altarpiece) illustrating episodes from the Passion of Christ. The sequence, which can be reconstructed from surviving panels now in other collections, included the Betrayal of Judas, the Way to Calvary, the Crucifixion, and the Lamentation, and concluded with this panel of the Resurrection.

***

Easter Wisdom

from Bob Beverly’s Find Wisdom Now blog

Easter Wisdom Do you know the poem by John Updike called “Seven Stanzas at Easter”? In it Updike wrestles with the ideas put forth by various ministers and theologians that the resurrection of Christ may not have been a bodily resurrection, but merely a believed story that is only important because it symbolizes some general nice truths like “You can start over” and “Try freshening things up a bit” and “Don’t give up your hope.” In their sense Easter is sort of a Spring like symbol, but not an actual occurrence.

As a psychotherapist, I’m all for hope and fresh starts and starting over. But if I were going to use Easter as a symbol, I would add a few dimensions that aren’t quite so delicate and soft. Now I certainly cherish soft and delicate things. Who does not delight in flowers, bunny rabbits, and children? But Easter as a symbol can be harder, louder, and more explosive because Easter represents much more powerful wisdom.

Ponder the Easter story and I think you’ll agree…

Easter is massive interruption. It is a new world dawning from out of nowhere. Easter is the idea that you will be helped by a greatness that is far greater than you. Easter is mind-blowing alternative—a powerful onslaught to the way you thought things were going to be. Easter is “this way of being and living is dead and gone”—here is something else, the totally unexpected, the fresh beyond imagination new beginning.

In this sense, Easter is one huge stop sign and one unforeseen giant green light beckoning you to a whole new world.

Easter is an ax.

It is a cataclysm. It is an “Oh my God” phenomena.

Easter is the miracle we need.

Think about your problems. Don’t you need more Easter in you and outside you to demolish those problems? Don’t you need some unexpected reality to come along and move the stone of your deadness and wake you up to new life?

And is this not what happens so often when we do in fact finally and slowly change? Here we are chugging along with our problems and struggles and old habits and foggy ideas when along comes a movie, a line from a song, a sentence in a novel, a word from a friend, a shout from a therapist, a firm directive from a stranger—and suddenly we see the possibility that we no longer have to live this way and right now we can change and, right now, miracle of bigger miracles, we do change and, in a certain way, become unrecognizable.

William James was getting at this when he offered this advice on how to change our life:

Start immediately

Do it flamboyantly

No exceptions

My first therapist of long ago (the blessed Ralph Fogg from New Paltz, New York who retired and moved to North Carolina but who lives in my mind and heart forever) was getting at this when he used to tell me “Robert, progress is the enemy of getting well and you don’t need progress, you need a revolution.”

I offer the Updike poem not as part of a religious debate, rather as a symbolic warning that we be careful how we water down things down and make them manageable and cozy and tidy when in fact what we need is something that will not conform to our comfort—-but instead with its realness bring us the revolution we need.

***

‘Seven Stanzas at Easter,’ the only recorded version of Updike’s poem set to music. From the album Music for an Urban Church by Gregg Smith with the Saint Peter’s Choir and Thomas Schmidt