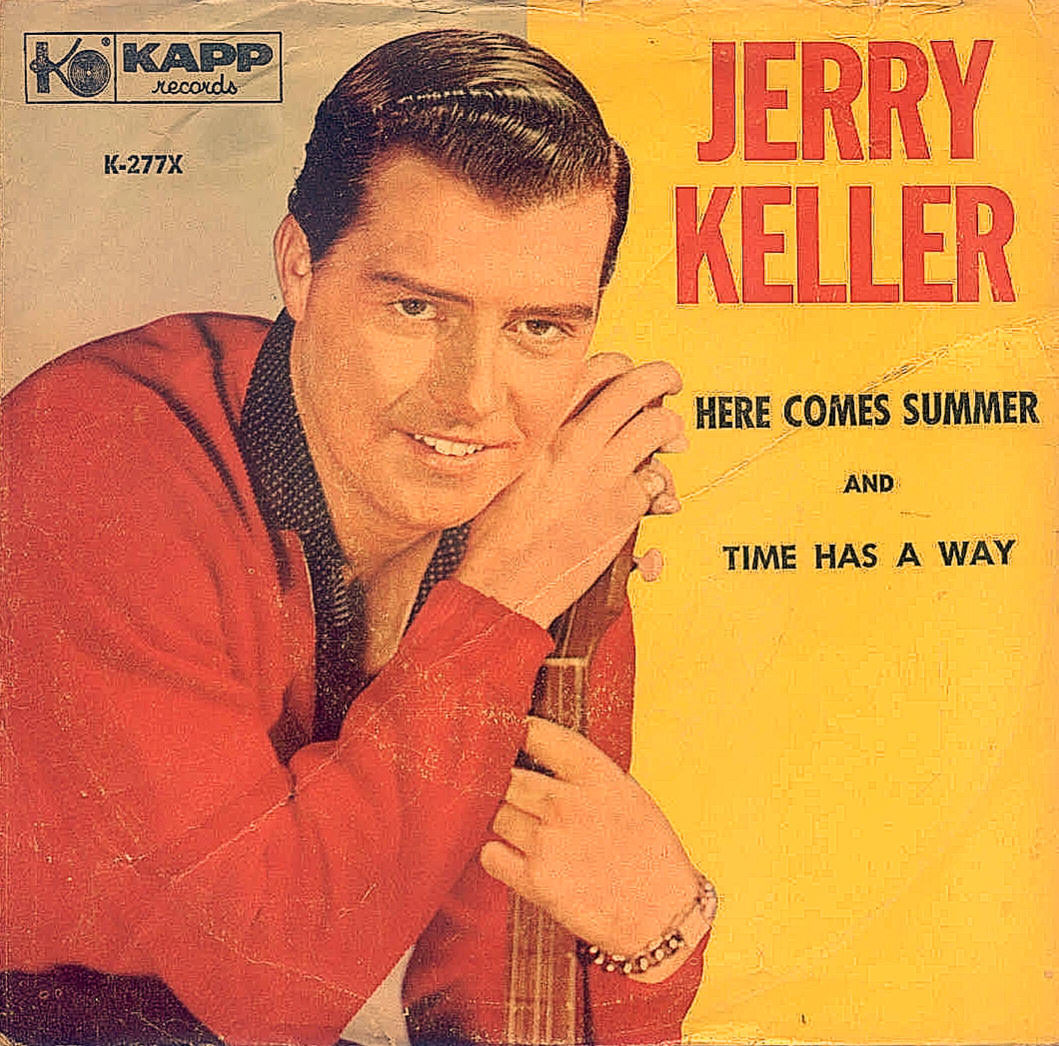

His seasonal classic ‘Here Comes Summer’ made the 22-year-old Jerry Keller a one-hit wonder. Now nearing 75, he has everything he ever wanted, including a satisfied mind and an impressive resume of achievements as a songwriter and jingles singer. His life has been as happy as his only hit.

From the archives of TheBluegrassSpecial.com, June 2012

You can call Jerry Keller a one-hit wonder; he won’t mind. He calls himself a one-hit wonder. As a recording artist, he had but one hit, and there’s no way to get around it. Being averse to B.S., Keller tells it as it is when you ask him about his recording career.

The danger in relegating Keller to one-hit wonder status is in diminishing his impressive accomplishments in the years after he secured a permanent place in the youthful memories of those of a certain generation by capturing a timeless spirit of the summer season in his 1959 smash, “Here Comes Summer,” a Top 20 single in the U.S. (peaking at #14 during a 13-week chart run), a huge #1 single in England and a million seller to boot. It was one of the standouts of an era when seasonal songs had a place in the Hit Parade, and a raft of great summer tunes rolled out on singles beginning in 1958 with Eddie Cochran’s “Summertime Blues” and the Jamies’ immortal “Summertime Summertime.”

Jerry Keller, ‘Here Comes Summer’ (1959)

Coming a year after the intense, piledriving “Summertime Blues” and the happy doo-wop bounce of “Summertime Summertime,” “Here Comes Summer” was soothing, laid-back and dreamy—it was for twilight time, when the heat was abating but the temperatures were rising in the robust libidos of teen boys free of classroom commitments and able to focus laserlike on courting their girlfriends.

Written by Keller himself, with a gently swinging small combo arrangement by the great Abe (Glenn) Osser (whose credits included arranging jobs with the likes of Bing Crosby, Charlie Barnett, Bunny Berrigan and the Paul Whiteman Orchestra; sax and clarinet positions in some of the great bands of his time, including Les Brown’s Band of Renown and Benny Goodman’s band; and extensive arranger/conductor credits with the television networks and Mercury and Columbia Records, which brought him into the orbits of outstanding vocalists such as Doris Day, Johnny Mathis, Patti Page and Georgia Gibbs), the tune begins discreetly with a lightly strummed electric guitar as another electric scratches along behind it, with a mixed-gender chorus adding soothing “ooo-oo-ooo-oo” fills and repeating the title sentiment back to Keller during the upbeat choruses. The song’s energy ebbs and flows, starting casually from a placid, steady groove until it kicks into a buoyant strut in the choruses and bridge as Keller and his fellow singers celebrate and anticipate end-of-school liberation. As a catchy twist, Keller interpolated a smidgen of the melody and lyric of Stephen Foster’s “My Old Kentucky Home” into the end of the verses, singing, “Oh let the sun shine bright/on my happy summer home.” (The Foster song was out of copyright and Keller was able to sample it, shall we say, royalty free.)

Jerry Keller serenades his wife

The song’s message is simple: school’s out and now there’s time to “grab my girl and run away.” Ever the romantic, Keller has no grudge against school (“well, school’s not so bad but summer’s better…”), unlike the Jamies, whose song counsels, “Say goodbye to dull school days,” thus establishing a template for summer rock ‘n’ roll songs that would be honored right up to Alice Cooper’s “School’s Out” in 1972. (Eddie Cochran had his complaints too, but those were about being unable to find a good job in the summer—a theme with new resonance today.) Keller wasn’t after anything more lyrically than simply enumerating the various and sundry pleasures awaiting teens when the final bell rang in May—swimming, drive-in movies, double features, moonlight drives—but what made his song rise above the commonplace was the tactile effect he made with his depictions of loving, physical contact and the shadings he employs with his smooth tenor voice when phrasing those lines so that listeners feel every sensation he describes: “Walks through the park ‘neath the shiny moon/When we kiss, she makes my flattop curl” (“The song is dated right there,” Keller says now); “It’s summer/I feel her lips so close to mine…When we meet our hearts entwine…”; “Drive-in movies every night/double features/Lots more time to hold her tight”; “I wanna hold my girl beside me/sit by the lake ‘til one or two/go for a drive in the summer moonlight/dream of a love, the whole night through.”

“Here Comes Summer” is nowhere near as well remembered as “Summertime Blues” or any of the Beach Boys’ summer classics, but it ranks with the season’s finest songs and gets extra points for being a true, happy summer love song, anticipating joys ahead. Feelin’ good is good enough, y’know.

A rare shot of Jerry Keller in concert

True to his big hit song, Jerry Keller himself is a most happy fella. Stout, grey-bearded, genial, and about to turn 75 on June 20, he still lives in New York City, on the upper west side near Lincoln Center, having moved to Manhattan in 1956 following two years of study at the University of Tulsa (Oklahoma) to pursue his dream of being a professional singer. Born in Fort Smith, AK, Keller and his family moved to Tulsa when Jerry was six years old. While attending Will Rogers High School (which would later give the music world Leon Russell, David Gates, Jamie Oldaker and Elvin Bishop; the town itself was home to Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys in the ‘50s as well), Keller was performing locally in theatrical productions and with swing bands (his big gig was with the Jack Dalton Orchestra in an establishment located on the top of a high hill on Memorial Drive, in what was then a desolate area of town but is now the high-rent district, or one of many high-rent districts; that club later became one of the city’s finest steakhouses, Shadow Mountain Inn, sans live music). During his Tulsa years he also formed the Lads of Note Quartet and the Tulsa Boy Singers. Occasionally he would partner up with another local singer of great promise, Anita Bryant, who attended Central High School in downtown Tulsa (“After I came to New York I knew her until she kind of went really nutsy after moving to Miami.”).

During his first year at TU, Keller sang in choral group that was invited to New York for a live broadcast on ABC Radio. For the golden-throated young vocalist, this trip was a dream come true writ large.

“I got a free trip to New York City,” Keller recalled in a recent interview as summer came early to Manhattan. “I would lay in my bed in Tulsa and listen to the Friday night fights from Madison Square Garden. I didn’t hate Tulsa, but I just felt like a big city was where I belonged. I was writing songs and singing and I knew I wanted to go up there. When I saw New York—we were just there three days—I knew I had to get back.”

When he returned home, Keller began plotting his Gotham return by pitching a local radio station on the idea of himself hosting a new afternoon pop show–a seemingly unremarkable idea had the station been devoted to anything but religious broadcasting.

“I went up and talked to the guy who owned it and said, ‘You need, in the afternoon, a pop show of some sort. It wouldn’t hurt you; you could still do your religious broadcasts early in the day.’”

He got the job. A year or so later, saving as much as he could afford to put away, he had enough to buy a Greyhound bus ticket to New York City. Off he went, riding three days and three nights to get there, “and loved every minute of it.”

Jerry Keller, ‘If I Had a Girl’ (1959), another beautiful Keller ballad. Originally a hit for Rod Lauren, Keller’s version was the flip side of his charting single “Lovable.

Once in Manhattan, he rented a small apartment, then took a job as a messenger at Asiatic Petroleum near Radio City Music Hall. One of his messenger trips took him to the building where The Ed Sullivan Show held forth, and in its lobby directory he found a listing for a vocal coach. After auditioning and being encouraged by her response—“she said, ‘You’re raw, but you have a good voice and talent, and if you’re serious, if you want to come back, I charge fifty dollars a lesson.’”—he knew what he needed to do.

Back to Tulsa went Keller. He finished his second year at the University of Tulsa, hopped the bus again and returned to New York to study with the vocal coach while honing his songwriting.

Before leaving Tulsa, Keller had promised his mother he would find a Church of Christ to attend in the city, and so he did, on Madison Avenue and 80th Street. On his second visit to services, he met the young fellow who was leading the church choir in song. It was Pat Boone, then a Columbia University student in the midst of a red-hot career that found him selling records on a par with Elvis and very nearly as much of a singing idol as the King, being the clean-cut mama’s boy to Presley’s raucous Hillbilly Cat. Generous and supportive, Boone befriended Keller and sent the aspiring singer to Marty Mills, who was managing both Boone and Mel Torme at the time. Mills was from a legendary music industry publishing family: his father, Irving Mills, had essentially built the modern music business, as a recording artist, songwriter (he co-wrote “Lovesick Blues” for a Broadway show years before it became Hank Williams’s career launching hit), arranger, producer (he was the first to team black and white musicians together in the studio, over the objections of executives at Victor), publisher, agent and manager (he discovered and managed Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Lena Horne, Mae West, Milton Berle, the songwriting team of Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh and employed Hoagy Carmichael as a staff songwriter at his Mills Music publishing empire). Taking a liking to Keller, Mills championed him to label executive Dave Kapp, at Kapp Records. An audition for Kapp produced a recording contract, and Keller was off to the races.

“Dave Kapp liked me because I was clean cut—Dave badmouthed all these rock ‘n’ roll guys,” Keller recalls. “They scared him to death; it was a world he didn’t know about.”

Kapp put his A&R chief, Richard Wolf, together with Keller and booked a four-song recording session at Capitol Studios. Kapp wanted ballads, the better to showcase Keller’s smooth style. After completing three songs—including one Osser figured would be the A side of Keller’s first single, a winsome ballad titled “Time Has A Way”–Osser asked Keller if he had anything worthwhile to fill out the remaining twenty minutes on the clock.

Keller: “I said, ‘You mean one of my songs?’”

Osser: “Yeah. Sing something.”

Keller mentioned that he had a song called “Here Comes Summer.”

Osser: “Sing that one for me!”

Keller performed the song, the background singers were listening in another room as he played and sang, and in about five minutes Osser had sketched out the chords. Osser: ‘It’ll be a throwaway, but we’re using the time.’

“So we did it in twenty minutes, two takes,” says Keller. “‘Session’s over. Thanks, everybody!’

“My mouth was hanging open. I’m a kid from Oklahoma who’s now been doing a session with professional singers and the Glenn Osser Orchestra. Now, for ‘Here Comes Summer’ they sent the violins home; we just used the rhythm section. So they said, ‘Look, it’s a waste tune, but ‘Time Has a Way’ we’re gonna push. We’re gonna take ads, we’re gonna work everything, and we’ll throw ‘Here Comes Summer’ on the back.”

Jerry Keller’s tender 1959 cover of Sonny James’s classic 1956 #2 hit ‘Young Love.’ Keller cut the song for his first (and last) album, Here Comes Jerry Keller, the American version of which did not include his big hit, ‘Here Comes Summer’

Keller had written “Here Comes Summer” while sitting in bed in his small apartment. While perusing the latest issues of the trade publications Billboard and Cash Box, it occurred to him that a song addressing a certain season might have commercial potential.

“The title came to me,” Keller recalls of the song’s genesis. “I was thinking of a summer song, and I thought, Well, it’s still early in the year so maybe ‘Here Comes Summer’ would work. When that happens, the melody pops into my mind to go along with that—‘Here comes summer…’ And I remember playing around, and then all of a sudden I did get the thought, ‘So let the sun shine bright on my happy summer home…’ Once I got that, then the rest was pretty easy. A friend in music publishing reassured me that the Stephen Foster quote was out of copyright, and I’ve always loved that ‘let the sun shine bright’ hook, so I used it.”

Able to play “a little guitar, a little piano but neither one well at all, but I could accompany myself on guitar,” Keller wrote songs as he had learned to sing them in church—in shape note style. “I can write a melody using the shape notes and you put it in any key you want. But of course when I came here I had to find someone who could take that and convert it into a regular lead sheet.”

Keller nods when it’s mentioned how he really makes you feel “the lips so close to mine” and the embraces. The lyrics were not tossed-off fluff. “I really related to those lyrics,” he says. “I was married for twenty-five years and now have had a relationship for twenty years. But the deepest in love I ever was was with a girl in high school, and I was thinking about her when I wrote that song. It’s just the way it is. Sometimes those times happen and you know you’re not gonna get ‘em back.”

Shipped as the B side of “Tomorrow Has a Way,” “Here Comes Summer” took off when big-time Buffalo, NY, disc jockey Dick Biondi got no response from his first four plays of the A side; on the fifth play, he accidentally flipped the disc over and aired “Here Comes Summer,” and the switchboard lit up. He played it again later, and requests flooded in

“Dick Biondi broke the record wide open,” Keller says, adding with a laugh: “And he later got a Cadillac for it. But that’s a whole other story.”

Then Dick Clark sniffed out the single, and Keller suddenly found himself making repeat appearances on American Bandstand. Other stations across the country added it to their playlists, and it began rising on the chart. Keller, with Duane Eddy, played the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa, in what was the first concert held in the venue following the plane crash that claimed the lives of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper. He toured England to rousing reception, doing shows with superstar Cliff Richard. But a cloud was hanging over Keller’s head during the England tour: prior to leaving he had received greetings from the United States Army, apprising him of his future for the next two years as a draftee G.I. Finagling a postponement so he could honor his contractual commitments, Keller completed the British shows and returned to start basic training. Being a good athlete and an intelligent man, he was named the outstanding trainee in his boot camp and sent to Fort Bragg, NC, for Green Berets training. Unlike Elvis during his Army years, Keller was not given leave to continue his career, and the two years on ice effectively insured his one-hit wonder status.

‘I’ll Put on Some Rock n’ Roll Music,’ Jerry Keller (1959)

Returning to the States after his tour of duty, Keller began courting, and eventually married, a woman from Fayetteville, AK, who gave birth to two children by him. The songwriting fire still burned in his belly, but leaving the spotlight as a performer was an easy decision, because that particular fire had been extinguished, after never burning brightly in the first place.

“To tell you the truth, I love music and I have an ego, but it’s not the kind that’s driven by being onstage. There were times when I was in London—I played a week at the Empire Theater in Glasgow and the girls were screaming and hollering–and I didn’t hate it, but there were nights when I wish I could have done something else. I’d rather have been at home watching a football game. Now all the guys, the good ones I played with all that time, the Avalons and whatever, they would rather be onstage than anywhere else in the world. And you need that to make it. I think the audience can tell the difference. I could put on a nice little show, but it was just not something I craved. I knew I wanted to be in the music business and continue to write, that’s all.”

Jimmy Stewart, ‘The Legend of Shenandoah,’ written by Jerry Keller for the 1965 Civil War movie, Shenandoah

Writing and “that’s all” worked out pretty well. Keller amassed an impressive songwriting resume—a Top 100 single for Andy Williams in 1964 with “Almost There” (Top 10 in the U.K.—Keller says having a song on an Andy Williams album back then was “an annuity”); the English lyrics for Francis Lai’s soundtrack for Claude Lelouch’s classic date movie from 1966, A Man and A Woman (the title song was recorded by Ella Fitzgerald, Matt Monro and Johnny Mathis, among others); “The Legend of Shenandoah,” a signature recitation by Jimmy Stewart in the 1965 Andrew V. McLaglen-directed Civil War film, Shenandoah; “How Does It Go,” a non-charting single for Rick Nelson in 1965; the soundtrack for the 1965 William Castle-directed horror film starring Joan Crawford, I Saw What You Did; and the soundtrack for 1969’s Angel In My Pocket, starring Andy Griffith in a film that bombed and has never been released in any format on home video, but is ever timely, owing to its storyline pitting families of different political persuasions in a small town power struggle and an ensuing conflict between church and state.

Apart from his own “Here Comes Summer,” Keller’s biggest chart success as a writer came in 1966, when The Cyrkle followed its #2 debut single “Red Rubber Ball” (co-written by Paul Simon and The Seekers’ Bruce Woodley) with a #16 single, “Turn Down Day,” co-written by Keller (lyrics) and the late David Blume.

The Cyrkle, ‘Turn Down Day,’ written by Jerry Keller and David Blume. The second Cyrkle single was a Top 20 hit (#16) in 1966, following the band’s #2 debut that year with the million selling ‘Red Rubber Ball,’ co-written by Paul Simon and the Seekers’ Bruce Woodley

Jerry Keller’s demo of his song ‘Turn Down Day,’ lyrics by Keller, music by the late David Blume.

Comes the ‘70s Keller’s fortunes rose again when his services were sought by an ad agency hired to retool Pepsi’s image for the younger generation. He found himself part of an elite group of first-call jingles singers in Manhattan, “doing eighty percent of the commercials on television, and my income jumped from twenty-five thousand dollars a year to, in two years, two- and three-hundred thousand dollars, from residuals. So that’s when I was able to establish myself, and I was very happy, and I was good at it. I never had a hankering to get back into the record business.”

During his jingles singing years, Keller, a member of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) as well as ASCAP and AFTRA (American Federation of Television and Radio Artists), took acting lessons and appeared in some off-Broadway productions; he landed a cameo as an orchestra conductor in the 1977 movie You Light Up My Life, thanks to a professional friendship with the unstable Joseph Brooks, who wrote Debbie Boone’s mega-hit title track but was a troubled, violent man who recently committed suicide while under indictment for raping or sexually assaulting 11 women he had lured to his apartment over a three-year period from 2005 to 2008, and whose son Nicholas is accused of killing his own girlfriend at a downtown hotel (see “The Curious Case of Joseph and Nicholas Brooks” in New York magazine).

Jerry Keller’s doo-wop-influenced teen misery ballad, ‘Never Wake Up’

“Joe, I did a lot of jingles with him. He was genuinely crazy,” Keller says. “Even at the time he was doing a lot of successful jingle work, he was a nut case. He wanted me to partner with him and invest money with him, and I always nicely said, ‘Joe, it’s just not my cup of tea.’ I always felt he was a very emotionally needy guy. I even knew the son, when he was a little boy, who’s now apparently murdered his girlfriend in that hotel. It was just a nutsy family. I would show up on sessions but socializing wasn’t something I wanted to do.”

‘I was draggin’ instead of drivin’’: Jerry Keller’s near-teen-tragedy song, ‘Be Careful How You Drive, Young Joey’

Finally, Keller, who had “saved every penny I could,” checked his bank account, thanked Susan Hamilton, the agency head who had hired him to do jingles in the first place, “and even Joe Brooks,” and quit the jingle business.

“I am retired,” he answers when asked how best to describe his life today. “I have a general passion for life, I always have had, and I love to travel. As soon as I started making serious money I put every penny I could into the pension plans and all that stuff, doubled that up in the 401–I said, ‘I want to travel.’ I’ve been to Russia twice, I’ve been to China. I love (traveling) and my wife loves it as well. She worked for Xerox for many years. Sometimes we travel together, sometimes I go out on my own. I’ve always loved traveling. So I keep very busy and I have my little publishing stuff, but I do very little on it. No, I’m definitely retired and I have been since I was 55, basically.”

Jerry Keller, ‘There Are Such Things,’ another choice Keller love ballad from 1959

He’s had offers to do oldies shows and turned down all of them. “I’ve never had any desire to do that. I appreciated being asked, but no. I enjoy going and seeing some of them, but anonymity to me is one of the greatest things I’ve ever had, and I have discreetly tried to keep it.” His son Shane found out about his father’s music career by accident, and, with dad’s permission, put up a website, now gone, that included audio clips of many Keller recordings (including those featured on his only album, Here Comes Jerry Keller, issued by Kapp but without “Here Comes Summer” on it because “Dave Kapp was a purist and he didn’t want to spoil the ballads with the uptempo song.” England Decca, however, refused to accept the album without its big hit single, so the English version of the album did include the timeless summer hit that inspired the album’s title). He routinely declines interview requests, but chose to do this one owing to yours truly’s roots in Tulsa and Oklahoma.

“I was not ever driven to be famous,” Keller says with a firmness that lets you know he means it. He likes being a one-hit wonder. He’s got everything he ever wanted, maybe more. He could curse his fate—being drafted at the moment he was on his way to being one of the hottest stars in the pop firmament—and could claim Uncle Sam short-circuited his dream, but he wouldn’t buy such a story himself or expect anyone else to, either. For a long, long time Jerry Keller has had a good life, and he’s still enjoying the ride. No regrets, no excuses.

“I wanted to be in New York and I wanted to make money so I could do what I wanted to do and live like I wanted to live. And I raised a wonderful family, a boy and a girl here in Manhattan. When things started getting good I bought a brownstone down in Chelsea and we lived there and the kids went to private schools. But I never craved the spotlight. If anything, one of my favorite things is to walk into a hardware store where nobody recognizes you and you can look at nuts and bolts for as long as you want.

“Some of us are just weird that way.”