By David McGee

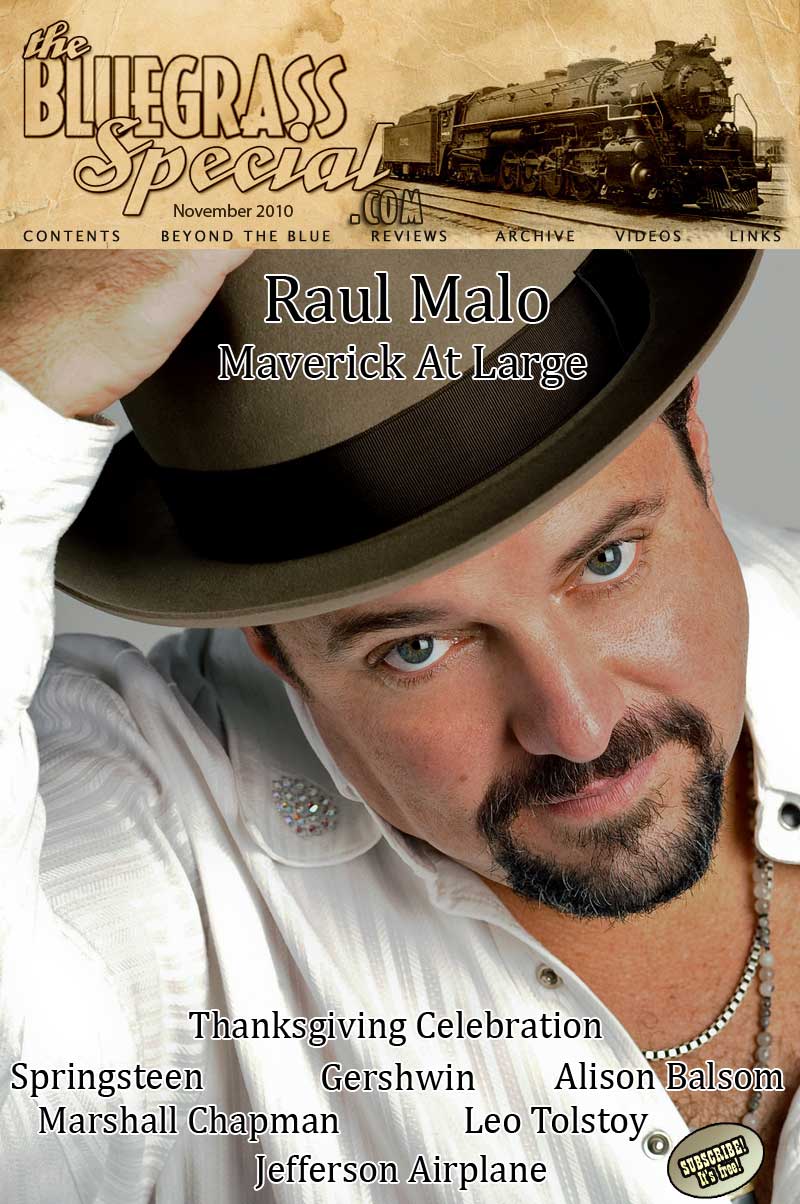

Raul Malo onstage: ‘This record is about as honest a representation of me as I can possibly put out there.’

At a few minutes after 8 p.m. on October 22, Raul Malo and what turned out to be a tight, precise but fiery quartet of musicians emerged from the backstage curtain at B.B. King’s club on 42nd Street in the heart of Times Square, New York City. Those in the packed house who were familiar with Malo’s stirring new album, Saints & Sinners, his second for the Fantasy label and sixth solo effort in all, immediately recognized and applauded the first plaintive, Spanish-tinged notes pouring forth from Kullen Fuchs’s trumpet (as the night wore on, multi-instrumentalist Fuchs would turn out to be a very busy cat indeed), these being but prelude to the nattily tailored (grey slacks and a casual white shirt with red trim, a neatly trimmed goatee and his jet black hair now grown out again and slicked back from its close-cropped style of 2009’s Lucky One album) Malo’s shimmering guitar solo impeccably crafted on a cream-colored Fender Mustang, before the rest of the band kicked in and pushed the percolating groove forward as, some two minutes in, Malo finally let loose with the magnificent voice that has earned him rightful praise as one of the finest vocalists of his generation. The song was the first cut off the album, the title track, the Malo-composed “Sinners & Saints.” Without losing stride, the band finishes one tune and immediately segues into another Malo original, the album’s second track, the honky tonk influenced “Living for Today,” a none-too-veiled indictment of a disposable, intolerant society too focused on immediate rewards and willingly blinding itself to the long-term consequences of its decisions. “We tried giving peace chance,” Malo intones at the song’s lone solemn point, “the only thing that’s wrong with that/we been at war since I was born/Ancient Rome has come and gone/the lesson’s there for all of us/what will we do with all we know?” (Malo was born in 1965, FYI.) After that, and again without pause, Malo and company tear into the cheery Tex-Mex sprint, “San Antonio Baby,” the album’s third track, a peppy, accordion-fired plea for reconciliation soaring aloft on the strength of one of Malo’s patented buoyant melodies, an occasion for two well-appointed 40-something (they said so) blonde sisters at the bar to begin shaking and shimmying their shapely hips, and momentarily stealing the show from the star, at least for those seated in the back of the room.

‘I literally would wake up in the middle of the night going, ‘My God, is this any good? Am I crazy? There’s a horn intro on this thing and it goes on for two minutes.’ You know?’

Breaking from the album sequence by skipping over the moving treatment he gives Rodney Crowell’s lacerating beauty, “‘Til I Gain Control Again,” on record, Malo goes acoustic for another self-penned gem, “Staying Here,” which here does not have the benefit of the disc’s creamy female choruses courtesy The Trishas. Even in its comparatively stripped down form, the song is an effective evocation of late-‘60s Nashville country with its straightforward story of a heartbroken loner reflecting on his lost love set to a haunting, lilting melody (sounds a lot like a Mac Davis song, in fact) rendered by Malo with a low-key, reportorial intensity designed to be but a thin mask veiling his sorrow. A tasty Spanish-inflected run on the gut-string is an atmospheric touch lending the song a heightened air of romantic desolation.

The Mavericks, ‘Dance The Night Away’ (live at the Royal Albert Hall), from the band’s masterpiece, Trampoline

Seven songs into the set Malo first references the past–much to the delight of the two bopping blondes at the bar–with a beautiful treatment of the Mavericks’ 1994 hit single, “O, What a Thrill,” from the band’s What A Crying Shame album, then stays in the richest of all Mavericks territory, the band’s penultimate album and genuine masterpiece, 1998’s Trampoline. As if acknowledging this truth, Malo would perform two Trampoline songs, the first, following “O, What a Thrill” being the beautifully textured treatise sung by a man determined to reclaim his lost love, “I’ve Got This Feeling,” with its determined, somber verses exploding into triumphant choruses that Malo’s husky, bold tenor eats up for maximum dramatic impact; and near set’s end, a raucous celebration centered on the rambunctious, horn-fired, Spanish-tinged “Dance The Night Away,” an impossibly infectious shuffle driven by Malo’s steady thumping acoustic guitar and Fuchs’s exuberant trumpet blasts that breaks into the catchiest chorus imaginable–“I just want to dance the night away/with senoritas who can sway/right now tomorrow’s looking bright/just like the Sunday morning light”–resulting in the two blondes at the bar gathering a couple of other comely females nearby and announcing “a train!” then proceeding to snake their way, with hands on each other’s swaying hips, through the aisles of B.B.’s club until they wind up at gathered en masse at stage right to, naturally, dance the night away. Returning for an encore, Malo and company immediately streamrolled the crowd into silence with a magnificent, spiritually resonant take on Saints & Sinners’ closing number, “Saint Behind The Glass,” written by Los Lobos’ redoubtable David Hidalgo and Louis Perez. This enigmatic story, seemingly a series of random verses depicting the powerful pull of an omnipotent, omnipresent higher power, is the occasion on record for one of Malo’s most nuanced vocals–a stunning blend of power, reverence and mystery–and a throbbing arrangement keyed by Malo’s own pulsating organ textures. At B.B.’s, Fuchs is handling the organ duties, and the sheer sonic power of the instrument’s carousel-like timbre melds with Malo’s vocal to deliver the elliptical lyrics’ awesome emotional punch, steadily building to a glorious finale the audience acknowledges with the rapt applause of those whose souls have been moved by the unfolding spectacle. Two songs later Malo sends everyone home with “Moonlight Kiss,” from last year’s Lucky One, its Latin flavor bringing the set full circle, back to where it began, smoldering south of the border.

‘Saint Behind the Glass,’ written by Los Lobos’s David Hidalgo and Louis Perez, performed by Raul Malo on his Sinners & Saints album. ‘The saint behind the glass could be a little fixture behind the glass that sees everything, sees your whole life, sees who comforts you, who consoles you. That’s a very old world thing; a very old generational thing. But the imagery is so beautiful in that song, and it reminded me of my childhood. I thought, If I can pull this off, this will be a beautiful end to the record.’

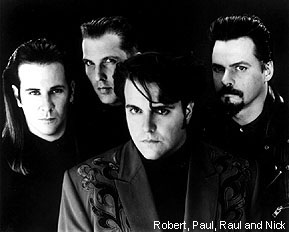

Raul Francisco Martin-Malo Jr. was born in Miami on August 7, 1965, descended of Cuban heritage. Following their chance meeting in a record store, he and bass player Robert Reynolds formed the Mavericks, adding Reynolds’s friend Paul Deakin on drums and guitarist Ben Peeler (later supplanted by David Lee Holt, who was in turn supplanted by Nick Kane–guitarists always occupied an odd, transitory spot in the lineup). From the start Malo wrote the band’s original material, and otherwise the Mavs covered a wide range of music reflecting both Malo’s Latin background and all the musicians’ interest in classic country and traditional rock ‘n’ roll. An eponymous 1991 album for the Cross Three label drew the attention of MCA Nashville executives, and soon the band was Nashville-bound, cutting its well-received, Don Cook-produced MCA debut, From Hell to Paradise, which not only displayed the quartet’s cross-cultural leanings but also included Malo’s scathing (and timely) indictment of hypocritical televangelists, “End Of the Line.”

The Mavericks were critical favorites from the git-go, and built a devoted following over the course of three more MCA albums–including the aforementioned work of sheer brilliance, Trampoline, the most cohesive and comprehensive showcase of the band’s multitude of influences in a nominally country album that stayed true to the Mavs’ ethos in recognizing no musical boundaries, a stance that can be traced back in country history at least as far as Jimmie Rodgers, who recorded with Hawaiian musicians, with the Carter Family, and with Louis Armstrong to boot–and a 2003 self-titled CD for the Sanctuary label that turned out to be the end of the line for the band that had made its debut on record with a self-titled album twelve years earlier. Alas, abundant sales and regular radio rotation were not in the Mavericks’ cards, and after the Sanctuary album had run its course, Malo officially left the Mavericks for a solo career that has turned out to be every bit as adventurous over the course of six albums as the Mavs were in their six-album history, but is most notable for the increasingly Latin focus of his original songs. Always, though, there is the voice, a natural wonder of near-unparalleled beauty in its operatic muscularity, romantic melodicism (those hip shaking blondes at the bar were equally smitten and swooning at Malo’s balladic interludes, trust me) and rich timbre. Moreover, as a writer steeped in the lyrical vernacular as learned from studying great songwriters from a variety of disciplines (but not least from those literate, sophisticated composers represented in the Great American Songbook), Malo is fashioning a imposing catalogue of copyrights that includes some topical fare along with poetic explorations of the state of being in love, yearning for love, recapturing lost love. On Saints & Sinners, Malo’s songs (six of the nine tracks are his originals), so rich in melody, so incisive and heartfelt lyrically, so exuberantly and unselfconsciously multi-cultural in ambiance, are nothing less than the sound of life itself, songs of flesh, blood and bone. To paraphrase Johnny Cash, one of Malo’s idols, flesh and blood needs flesh and blood, and these songs are what we need.

On that note, and back to the B.B.’s show, a few things beyond the sheer musicality of Malo and company’s performance stood out for this veteran Malo follower. Catching up to him the next day, as he was preparing simultaneously for a show that night in Port Washington, L.I., and for a European tour immediately thereafter, I opened a wider discourse into the tao of Sinners & Saints by asking him to address some marked differences in the set he played at the same venue in 2009 and the one he delivered the night before.

***

Raul Malo, ‘Sinners & Saints,’ title song from new Fantasy album, written by the artist. ‘I think everybody is part sinner, part saint. Some more sinner than others, perhaps some more saint than others. The duality of life–that’s one of the points of this record.’

I noticed a few things different about this show, and for all I know it was the result of time constraints, since there was another act coming on after you and the house had to be cleared for it. You spoke from the stage far less than I’ve heard you do in previous concerts; you didn’t introduce yourself or the band, or even mention the new CD. But most important, for me, having seen you through the years, you were playing a lot more guitar, as you do on this record, really stepping out as a guitar player. Was one of your goals with this record to make a statement as an instrumentalist as well as a vocalist?

Raul Malo: Well, it really didn’t start out that way. It kind of evolved into that. When I left the Mavericks I started playing more and more guitar, and started implementing it into songs as I saw it, not really coming from a guitar player’s perspective. Coming at it more from, I guess, a composer or arranger side of things. I started playing more what seemed to me guitar parts as opposed to guitar solos. That’s what I’m really more interested in. I’ve resisted getting a guitar player because I like the space that is created by the fact that there isn’t a guitar player noodling all over the place. And so because of that, and honestly because I don’t really have the skill set to be doing that; I’m not really a guitar player in the sense of somebody like Vince Gill or Keith Urban—those guys are dedicated guitar players–I play parts in my songs that I think work. So I approach it from that side. I didn’t set out to all of a sudden be the guitar player. It just kind of evolved into what I’m doing.

When you talk about playing guitar parts, do you intend to use it to create certain textures within a song? Is that the point?

RM: Absolutely, yeah. And part of that is making sure that it’s the sound that I want. It took me awhile to find that sound that I really dig. In the Mavericks I played some guitar, but there was always a guitar player. I didn’t really have to worry about it. And in some ways I miss that because it puts some added pressure on me–now I gotta play the solos. But I have fun; I do enjoy it. And as far as last night, as far as banter with the audience, first of all, we got in there and nobody told me it was a dinner show. Not only was it a dinner show, there was a curfew. We had to be done by a certain time. It was like, “You gotta be shittin’ me.” So it kind of took me out of…really made me decide, well, we’ll just play on, not waste too much time, try to get in as many songs as possible, try not to say anything stupid.

‘Living for Today,’ Raul Malo, from his Sinners & Saints album

What were you goals when you set out to do this album? How was it supposed to be different from what you’ve done before?

RM: For starters this one is about as honest and complete a representation of what I’m thinking or what I’m feeling, what I want to say, with no outside influence. And that evolved too. I usually work with a co-producer and co-writers, and it’s a communal effort. I enjoy that, too. I love making music that way, especially with good partners that you can have fun with. There’s something to be said for making music that way. But as I got into this record, and I started recording at the house, I guess I just got more and more comfortable, and I was digging the result. And at some point you have to go, I’m either going to take all the blame or get all the credit. And that’s okay. But there was a point where you go, I’m laying it all on the line right now, and that’s okay. We’re gonna have to go with it. I’ve never really been taken out of my own comfort zone as much as I was on this record. So that was part of the result. To me this record is about as honest a representation of me as I can possibly put out there.

You say you were taken out of your comfort zone, but that was something you chose to do, right?

RM: Yeah. Again, as it evolved, the more I did it, I knew I was going to keep going. This isn’t how I worked before. I would wake up in the middle of the night going, “My God, is this any good?” And not have anyone to bounce any ideas off of or (laughs) somebody to talk me down. It’s like, well, you either jump or get to a studio, one or the other. I was being facetious there, but I literally would wake up in the middle of the night going, “My God, is this any good? Am I crazy? There’s a horn intro on this thing and it goes on for two minutes.” You know? “Are people going to get it?” You just go through all these feelings. You have to remember, too, nobody’s really heard it. So aside from my family, or close friends, whomever was around, nobody had really heard the record, nobody knew what I was doing. It was a little nerve wracking, but again, I think that’s kind of the point. If we’re really going to call ourselves artists, that’s the whole point of art, I think. At a certain point you have to push not only the listener, but yourself, and perhaps take everybody along with you to that place where it’s like, “We’re hanging on here, but okay, good, good.” You take everybody out of their expectations. I didn’t really know, initially, that I didn’t sing on this record for two minutes until somebody pointed it out to me. Then I went, “Oh, yeah, that’s true. I don’t sing on this record for two minutes. What was I thinking?” But honestly, I like the way it starts. It sounded like that’s the way this record should start. And again, it’s just a different way of making music. I grew up listening to so many records, and I remember sitting around listening to Pink Floyd records where nobody sang anything. You know? It didn’t seem to hurt them any. But it’s a different thing. I know people obviously want to hear me sing and all that, but this record was going to be a little different, that’s all, and I knew that from the start.

One thing about staying in your comfort zone—and you’re so well established and so beloved as a singer—you could have made a record that fans would have embraced, and it would have brought you news fans, but the element of surprise might not have been there, right? That’s what you get when you go out of your comfort zone.

RM: I think so, and that’s what this record was. It was honestly a surprise for me, too. I really had no idea that it would end up this way or that I would end up recording it this way. It just evolved and the more I did it the more it started to take on a cohesive form. That was a nice surprise (laughs). It is what it is. I enjoyed the process, I enjoyed everything about it, I really did. Even when it takes you out of your comfort zone and you’re in a panic mode, I enjoyed that too, on the level of, Maybe this is the way it’s supposed to be. Honestly, that’s why I ended up using that baby picture on the cover. When I first saw it I was like, “Oh, I don’t know that I want to do that.” Even that was uncomfortable. But I thought, This thing is about as honest and bare a representation of me as I could possibly do, so here it is, here’s all of it.

‘‘Til I Gain Control Again,’ a brilliant cover of the Rodney Crowell classic, by Raul Malo on his Sinners & Saints album. Says Malo: ‘Late one night I got in the studio, turned on the microphone. There was nobody around, nobody. I just sang it, and it wore me out. I was just drained. I listened back and it wasn’t like a perfect vocal, but it had the emotion and it had the grit and it felt right to me. So I left it on there, warts and all. That was one performance all the way through, with no fixes, no nothing.’

I find the Latin element in your music becoming stronger with each of your new solo projects, and it’s quite pronounced on Saints & Sinners. I wonder if you find, as you get older, that you’re more drawn to that part of your heritage than you were as a younger musician. Is it showing up so much more in your music as part of an ongoing personal journey?

RM: I think that’s part of it. I think the other part of it is that, you know, when we were in the Mavericks, we were on a major label, and we were in the game–in the mainstream game. You know, they talk about the Latin element and all that, but they don’t really want it. You know what I mean? They don’t really allow it. I’ll never forget a phone call from our promotion man saying there was a radio station in North Carolina that was not going to play “All You Ever Do Is Bring Me Down.” They weren’t going to add it because it had an accordion solo and was too Mexican sounding. I’ll never forget that. I just thought, Okay, this is it, here’s the line drawn in the sand. And that’s that world. I’m not in that world anymore. I left that world, and I left that world not only for those reasons, but certainly that’s a big part of it. It’s a very rigid, very narrow world. They want you to do the same thing over and over again. The record label, once you have success doing one thing, that’s what they want. Over and over and over again. There’s no real artist development or any sort of moving forward, pushing the envelope. That’s why you have the music as it’s done today. You turn on the radio and it all sounds the same. You turn on pop radio it all sounds the same. The cool stuff is always going to be underneath the mainstream. That’s part of it too, that I don’t have any of those restrictions anymore. I’m not going to get played on mainstream radio, and that’s okay. I wish they would, but that’s not gonna happen. So you find your place, you find your audience, and hopefully they go with you on whatever musical journey you go. But the point is you can go on a musical journey. I don’t think making the same record over and over again is a journey; that’s a factory. To me that’s not how music works, at least not for me.

Topical songs are not new to your repertoire. We’ve touched on the Mavericks a bit here, and I go back to one of my favorite songs on that group’s very first album, “End of The Line,” which took on hypocritical televangelists at the moment they were omnipresent in our culture and right before a lot of them were sent packing under the weight of sexual and financial scandals. On this record you’re coming back with two songs that seem direct comments on the current climate in this country. One is “Living for Today,” and the other is more deceptive, “Matter Much To You,” because it sounds like a beautiful love song—you gotta listen to it. What inspired you to do not one but two songs of this nature? Even “Superstar” seems a comment on a disposable culture—“How quickly they forget.”

RM: Again, these are things that come from observing. Whether you’re an author, musician, composer, a newsman, whatever it is, people in the arts, I think part of what we do is observe. Comedians do this brilliantly; I think they’re the best at it. If you just sit back and watch, you’re eventually going to be affected by it and maybe it will inspire a song here or a song there, or a book, or an op-ed piece, or whatever.

“Living For Today,” the truth is I have a great pet, he’s about 12 years old, an American bulldog, and he’s like my favorite dog. His name is Rocco. Really just hanging out with him and being around him for so long, he embodies the phrase—the song was actually inspired by him—living for today. He lives literally for each day. And as a concept it’s a beautiful thing and it works for him. The problem is, it doesn’t work for us. We’re far more complex than a dog. He’s just worried about getting fed, having a bed, chasing a ball, and a place to poop—and even that, I have to say, he doesn’t worry too much about that either, that little son of a bitch. I gotta tell ya. As a concept it works great for him. The problem is we apply that concept to us and it doesn’t work, it hasn’t worked, it’s not working now. We’re depleting all our natural resources, we’re destroying the earth, we’re in a financial crisis, everybody’s living way beyond their means, we don’t ever live for tomorrow. We really should be living for tomorrow. The financial crisis, you look at—a friend of mine who works on Wall Street—and I’m not a financial person at all—was explaining to me that there’s a term they use for people who hold investments. The average hold now on an investment, he said, is something like seven seconds. That’s not investing; that’s a roulette wheel. So you have this mindset of the quick turnover. You see it all over. You see it in cities. Somebody will come in, buy a building, turn it into a disco, make money for three or four months—and I saw this on Miami Beach—it happens down there all the time—they make their money and then they close the joint out. It’s that sort of mentality, that make the money now-get out mentality, is part of our life. You see it everywhere. You see it in how we fuel our cars. Why are we still even messing with fossil fuels? Why? Of course, it’s the corporations, it’s money, it’s blah-blah-blah, all of it. And I understand all that. But at a certain point you have to go, When does it all stop? When do we really change? When we’ve run out of fuel? Because we’re going to at some point. And at what cost by then? When we’ve turned this whole planet into an arid desert? We’re seeding clouds, we’re changing weather patterns, strange things are happening all over the place, and there are still people arguing that there is no climate change, there is no global warming. I’m trying not to come at it from the political side. I would love to see the argument change and go from politics to a humanitarian conversation. When you have one out of seven people living below the poverty line, those aren’t strangers. Those are friends. Those are acquaintances. Those are relatives. You have over 50 million people without health insurance. Those are serious issues. Those are humanitarian issues, not political issues. Unfortunately, they get politicized and the partisanship takes over and the whole system is a big mess. And people fall by the wayside, and that’s where the real tragedy lies. We have these ridiculous arguments, and elections, people all fired up and nothing changes.

‘History waits for no one, by the way’: ‘Living for Today,’ from Sinners & Saints, Raul Malo

As soon as an issue becomes politicized, all progress towards a solution ceases. Takes it into a completely different arena, and nobody benefits. Nobody.

RM: That’s it. So that’s what inspired these songs. Yeah, I could have sat there and written a whole record of love songs, but I felt like I needed to say these things on this record. And not that it’s going to change things; it may not. But I think the fact that maybe if it inspires a couple of people to have these kinds of conversations, that might be okay.

No one needs to defend themselves when they cover a Rodney Crowell song as far as I’m concerned. But with regard to “Till I Gain Control Again,” of all the Rodney songs you could have chosen, why did this one fit best with what you wanted to do on this album?

RM: I think, first of all, it’s one of my favorites, and has been one of my favorites for a very long time. Honestly, I hadn’t set out to record it. I love the song and I thought, Well, I’d like to record it some day. But the more I listened to it and got into the head space of the song, I thought, I’m gonna try it. I started building the track and I recorded it, got the pedal steel on there, and at first when I was singing it I wasn’t really getting it; I wasn’t really liking it. I thought, It’s such a special song for me, and lyrically it fit the album perfectly, because it is about exactly that—the person who has gone there and now has to make amends for the past, embodying what we all do, that duality in life. I think everybody is part sinner, part saint. Some more sinner than others, perhaps some more saint than others. But that song to me totally embodies that duality of life. And one of the points of this record is that. So late one night I got in there, turned on the microphone. There was nobody around, nobody. I just sang it, and it wore me out. I was just drained. I listened back and it wasn’t like a perfect vocal, but it had the emotion and it had the grit and it felt right to me. So I left it on there, warts and all. That was one performance all the way through, with no fixes, no nothing. Most of this record is like that, but that one in particular, I remember saying, “I’m going to leave it like this, for better or for worse.”

I usually try to offer my own interpretations of songs and let the artist react to those to get the heart of the matter. You close with “Saint Behind the Glass,” by Los Lobos’ David Hidalgo and Louis Perez, and I must confess I don’t know what to make of one of the most beautiful songs you’ve recorded, and it was even more evocative live. What is your take on who is the saint behind the glass and why is he/she/it is so powerful?

RM: Man, that song, again, it was one of those songs, I’m a huge Lobos fans, those guys are buddies of mine. I love them. They are truly an inspiration. This song spoke to me for many reasons. First of all, the imagery. The saint behind the glass, that’s a very Catholic thing, and a very Latin Catholic thing. When I first heard that song it reminded me of being at my grandmother’s house. It’s funny, in talking to Louis Perez, that’s exactly what he was writing about, those images–the coffee in the air, the curtains blowing ‘round. As a Latin kid, you’d go to your grandma’s house and that’s what it was like. The saint behind the glass could be a little fixture behind the glass that sees everything, sees your whole life, sees who comforts you, who consoles you. That’s a very old world thing; a very old generational thing. But the imagery is so beautiful in that song, and it reminded me of my childhood. I thought, If I can pull this off, this will be a beautiful end to the record. Bringing the whole saints thing to a close. I tried to make it a little different from the Lobos version and do my own thing to it, but still maintain the integrity of the song. That’s what I tried to do, and I haven’t received any threatening emails from Louis, “Hey, you son of a bitch!” In fact, Steve Berlin sent me an email saying they loved it. So the pressure’s off. I can worry about other things.”

Originally published in TheBluegrassSpecial.com, November 2010