In the April 2011 issue of our predecessor, www.TheBluegrassSpecial.com, we began pondering the meaning and weight of John Updike’s poem “Seven Stanzas at Easter” via the perspectives of various theologians, ministers, religious philosophers, pundits and seminary students. In the 2011 installment we offered the story of the poem’s first publication as the winning entry in a church’s poetry contest, and how Updike won a $100 prize for it that he returned to the congregation, along with three essays centered on the poem’s multiple meanings. A year later, in our April 2012 issue, we expanded the feature to “Seven Voices on Seven Stanzas,” and now, here we are in 2018 with our seventh consecutive “Seven Voices on Seven Stanzas” feature, which, when you add them up, amount to 49 voices on “Seven Stanzas.” This doesn’t mean we’re cool or anything of the sort, but it does underscore the passions evoked and inflamed by Updike’s poem about Christianity’s defining event, the Resurrection of Jesus Christ—it has to be dealt with, year after year.

First, the poem, then off we go…

***

Seven Stanzas at Easter

By John Updike

Make no mistake: if he rose at all

It was as His body;

If the cell’s dissolution did not reverse, the molecule reknit,

The amino acids rekindle,

The Church will fall.

It was not as the flowers,

Each soft spring recurrent;

It was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled eyes of the

Eleven apostles;

It was as His flesh; ours.

The same hinged thumbs and toes

The same valved heart

That—pierced—died, withered, paused, and then regathered

Out of enduring Might

New strength to enclose.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence,

Making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the faded

Credulity of earlier ages:

Let us walk through the door.

The stone is rolled back, not papier-mache,

Not a stone in a story,

But the vast rock of materiality that in the slow grinding of

Time will eclipse for each of us

The wide light of day.

And if we have an angel at the tomb,

Make it a real angel,

Weighty with Max Planck’s quanta, vivid with hair, opaque in

The dawn light, robed in real linen

Spun on a definite loom.

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,

For our own convenience, our own sense of beauty,

Lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour, we are embarrassed

By the miracle,

And crushed by remonstrance.

***

Fresco from Kariye Camii, Anastasis, showing Christ and the resurrection of Adam and Eve: “Resurrection and Redemption — a new burst of creative energy…enlivened Late Byzantine painting. Artists produced masterpieces of mural and icon painting rivaling those of the earlier periods. A fresco in the apse of the parekklesion (side chapel, in this instance a funerary chapel) of the Church of Christ in Chora (now the Kariye Museum, formerly the Kariye Camii mosque) in Constantinople depicts the Anastasis…the Anastasis is here central to a cycle of pictures portraying the themes of human mortality and redemption by Christ and of the intercession of the Virgin, both appropriate for a funerary chapel. In the Kariye fresco, Christ, trampling Satan and all the locks and keys of his prison house of Hell, raises Adam and Eve from their tombs. Looking on are John the Baptist, King David, and King Doloon on the left, and various martyr saints on the right. Christ, central and in a luminous mandorla, reaches out equally to Adam and Eve. The action is swift and smooth, the supple motions executed with the grace of a ballet. The figures float in a spiritual atmosphere, spaceless and without material mass or shadow-casting volume. This same smoothness and lightness can be seen in the modeling of the figures and the subtly nuanced coloration. The jagged abstractions of drapery found in many earlier Byzantine frescoes and mosaics are gone in a return to the fluid delineation of drapery characteristic of the long tradition of classical illusionism.Through the centuries, Byzantine artists looked back to Greco-Roman illusionism. But unlike classical artists, Byzantine painters and mosaicists were not concerned with the systematic observation of material nature as the source of their representations of the eternal. They drew their images from a persistent and conventionalized vision of a spiritual world insusceptible to change.” (Gardner/Kleiner/Mamiya, 272)

***

If You’re Going to Believe, Then Believe

I’ve always had something of an ambivalent attitude towards John Updike. I’ve known his work for ages—he grew up in Shillington, PA, just a stone’s throw or so from where I grew up. He was raised a Lutheran, an upbringing that he seemed to struggle with as well as be marked by. I’ve loved his short stories as much as anything I’ve ever read, but sometimes been less than taken by even his celebrated novels. I don’t know why—perhaps they were too “earthy” for this kid. But it’s precisely the “earthiness” of “Seven Stanzas at Easter” that I love about this poem. If you’re going to believe, Updike seems to say, then believe. Stop trying to soften the edges of Christian faith or make it more acceptable. And I think he’s right—“modernize” the resurrection—by making it a metaphor or parable or the disciples’ dream or psychological experience—and you lose something essential not just of the story but of the very promise of God to remake everything as real and tangible and alive as God made it in the first place.

The post image, from the familiar Greek icon Anastasis (Resurrection), is one of my favorite images for Easter because it shows the usually placid Christ actually straining to pull Adam and Eve from the clutches of death and hell. I think it complements the sensibilities Updike expresses in his poem.

Blessed Easter, one and all!

Posted by David Lose (DJL) on April 8, 2012 at www.davidlose.net

***

On Easter and Updike

by David E. Anderson

Easter is not easy for most poets and writers, the difficult mystery of resurrection being more intractable than incarnation.

One of the best examples of the problem is perhaps the most famous Easter poem of the second half of the 20th century, John Updike’s “Seven Stanzas at Easter.” Updike identifies the difficulty in the opening line:

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

The crucial word in the center of the first line—if—starkly states what might be called “the Easter problem” and Updike’s insistence on the orthodox doctrine of the physical, bodily reality of the resurrection, even when hedged with the doubting if, provides a succinct but apt statement of one of the key themes of his work—the terror of death and the search for some sense, some promise, of overcoming, and he will not brook any evasions:

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

analogy, sidestepping, transcendence,

making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the faded

credulity of earlier ages:

let us walk through the door.

The tension between belief and doubt in the face of death, between faith and its opposite—certainty, and the need for resurrection run through all of Updike’s vast body of writing, from his early novels, stories, and poetry (“Seven Stanzas at Easter” was written in 1960, just a year after his first novel was published, and the poem was the winning entry in a religious arts festival sponsored by a Lutheran church on Boston’s North Shore) to his later work, including Due Considerations, his final collection of essays and criticism, and Endpoint, a posthumous book of poems published this month.

From a review of Updike’s final book of poems, Endpoint. Click here for the full review, posted on April 7, 2009 at Religion & Ethics Newsweekly

***

‘Easter Sunday Song,’ William C. Beeley, from his 1970 album, Gallivantin’

***

“Seven Stanzas at Easter” by John Updike

by The Rev’d Dane E. Boston

Joe Rawls, over at The Byzantine Anglo-Catholic, recently posted the poem below. I was very glad to be reminded of it. I don’t know much about John Updike’s personal faith, but these lines powerfully express the scandalous particularity of Christ’s Resurrection.

Eastertide (in which we still find ourselves, and will for another several weeks) is not about springtime and new life and the annual cycle of rebirth. It is not about a generalized spiritual hope. It is certainly not about the afterlife.

Rather, from the Easter Vigil through the Great Fifty Days—and on every Sunday of the year—the Church has the audacity to announce that the man Jesus Christ, who was crucified, died and was buried, on the third day was raised from the dead. It happened at Jerusalem, in Judea, while Pontius Pilate was governor and Herod the puppet King of the Jews, and in Rome Tiberius claimed the mantle of divine emperor.

And what Updike gets (and a fair number of preachers seem to miss) is that the particularity of it all is actually what gives the Resurrection of Christ its universal significance. Because the One Man has conquered death, all humankind has been set free from the fear of the grave. Because Christ was raised in his own body—though transformed and glorified—-“my flesh also shall rest in hope.” Because Jesus has become the first fruits of them that slept, so too must my corruptible body “put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on immortality.”

All of this (and much more!) is contained in the announcement that “The Lord is Risen indeed!” Here John Updike explicates it with poetic power (and an economy greater than this poor preacher’s).

Posted at www.daneboston.com, April 30, 2014. The Rev’d Dane E. Boston is the Rector of Christ Church, Cooperstown, NY. Prior to being called to Cooperstown, Dane served as Canon for Christian Formation at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Columbia, South Carolina and as curate of Christ Church in Greenwich, Connecticut. A native of Dunedin, Florida, Dane was ordained a deacon at R.E. Lee Memorial Episcopal Church in Lexington, Virginia, in November 2011. On June 5, 2012, the feast of St Boniface, Dane was ordained a priest at Christ Church Greenwich.

***

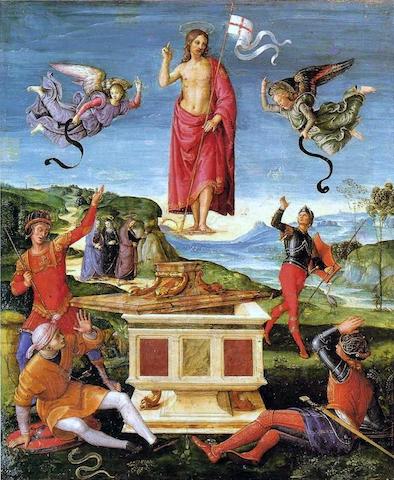

The Resurrection of Christ (1499–1502), also called The Kinnaird Resurrection (after a former owner of the painting, Lord Kinnaird), is an oil painting on wood by the Italian High Renaissance master Raphael. The work is one of the earliest known paintings by the artist, executed between 1499 and 1502. It is probably a piece of an unknown predella, though it has been suggested that the painting could be one of the remaining works of the Baronci altarpiece, Raphael’s first recorded commission (seriously damaged by an earthquake in 1789, fragments of which are today found in museums across Europe). The painting is housed in the São Paulo Museum of Art.

The Kinnaird Resurrection is one of the first preserved works of Raphael in which his natural dramatic style of composition was already obvious, as opposed to the gentle poetic style of his master, Pietro Perugino. The extremely rational composition is ruled by a complex ideal geometry which interlinks all the elements of the scene and gives it a strange animated rhythm, transforming the characters in the painting into co-protagonists in a unique “choreography”. The painting possesses an esthetic influence from Pinturicchio and Melozzo da Forlì, though the spatial orchestration of the work, with its tendency to movement, shows Raphael’s knowledge of the Florentine artistic milieu of the 16th century.

***

‘The Poem Speaks Our Language’

Here’s what I love about Updike’s poem:

- It gives the appropriate importance to the resurrection.

- It speaks our language.

When I say that it gives the appropriate importance to the resurrection, I mean that Updike sees this event as the central event in the Christian faith, with out, “the Church will fall.”

This has been my constant refrain against those who attempt to use science to assail Christianity. Most jump to Genesis 1 and 2 and attempt to refute the creation stories with evidence of a 14 billion year-old universe. I heartily agree with them and say: “Yes, I too think the universe is that old. Let’s also talk about the 4.5 billion year-old Earth!” If the story of Adam and Eve or either of the creation stories in the Hebrew Bible are shown to be ahistorical, the Church will not fail. These stories are interesting, but they aren’t the heart of the faith. The heart of Christianity is found in Christ and more specifically in his resurrection. Consider this: Jesus dies as the vast majority of his disciples have abandoned him. The resurrection is that event which brings them back together, galvanizes them, and reinvigorates them for the life of persecution that they will lead in the wake of the scandal.

For the Christian, the resurrection is the ballgame; it’s everything.

Second, I love that the poem speaks our language. It mixes in the language of quantum physics, biology, and medicine. pdike doesn’t ask us to shy away from the scientific implications of the resurrection; instead, he asks us to consider them part of the miracle. The resurrection is real, down to the amino acids involved and the existence of the angel in our dimension.

Thank you, Mr. Updike. May you rest in peace!

Posted at The Hebert (undated). The author is a Teacher and Assistant Chaplain at St. Mark’s School in Southborough, Massachusetts.

***

Painting by Oswaldo Guayasamín (July 6, 1919 – March 10, 1999, an Ecuadorian master painter and sculptor of Quechua and Mestizo heritage.

***

A novelist makes the case against turning the event into a parable…

“Seven Stanzas at Easter” is about the body of Christ in more than one sense, and its theme appears unambiguous: In for a dime, in for a dollar; if you talk about the Resurrection, you can’t turn it into a Jungian projection of a collective unconscious. But it’s a mistake to read “Seven Stanzas at Easter” a tract. The poem doesn’t weigh the historical or theological evidence for or against the Resurrection. It less about what happened or didn’t happen at the tomb than about how to talk about it. And its message is more equivocal than Job’s “I know that my redeemer liveth.”

Updike tips his hand with the “if” in his first line: “Make no mistake: if He rose at all.” That “if” modifies all that follows and turns the poem into a variation on Pascal’s wager, the idea that although the existence of God can’t be proved, a person should live as though it could be, because that position has all the advantages. Updike tells us to avoid sanitizing the Resurrection for our own comfort or because we can’t otherwise conceive of it. To mythologize the event, he warns, is to being “awakened in one unthinkable hour” and find that “we are embarrassed/by the miracle,/and crushed by remonstrance.” —excerpt from “John Updike’s ‘Seven Stanzas at Easter’ Answers the Question, How Should Christians Talk About the Resurrection?” By Janice Harayda, posted at One-Minute Book Reviews, March 20,2010

***

Seven Stanzas and a Stone at Easter

By Tom Gibson, April 30, 2014

There are some who say that today, Easter, is a celebration of an excess of imagination. John Updike, never short on imagination himself, says no: the Easter reports were about what happened.

It happened this way, or “the Church will fall.” The apostle Paul said the same in 1 Corinthians 15.

Easter is not an act of human invention, it is the world in full color. Updike is correct to insist that the surface event was never “transcendent” in the sense of unreal; yet there is at the same time a transcendence there that cannot be sidestepped, precisely because the event was real.

To follow Christ requires imagination, yes: not fairy-story imagination, but openness to reality beyond what we see on the surface.

Such openness is, sadly, not always evident. The other day I saw where an atheist blogger (who need not be named) had found “contradictions” in the resurrection accounts, including,

What were the last words of Jesus? Three gospels give three different versions.

Could Jesus’s followers touch him? John says no; the other gospels say yes.

Actually John tells us Jesus told Thomas to touch him, but not to cling to him. There’s a more consequential error on display here, though: a black-white requirement that the accounts be exactly the same or else be contradictory. Real people reporting real events tell stories differently even when telling them truly.

To live this way is to be stuck in a sad sort of stone literalism. Atheism in general implies a cold, hard world of stone. Nothing counts in the God-denier’s world but what’s on the surface, reality defined according to a cautiously contained and convenient beauty, the light weightiness of Max Planck’s quanta with the real life embarrassed out of it.

There is a stone in the story of Christ, too: it ‘s been rolled away.

Published April 20, 2014 at Thinking Christian

***

‘This Is Poetry in Action’

I wrote some lines earlier in Five Proofs of Christianity (WestBow, 2016):

I know as a Christian that Easter is our bedrock. Thirty-three years after the birth of Christ the resurrection occurred, without which, as Paul says, we are nowhere. Our hope is in vain. And we are of all people most to be pitied because we have believed in vain, Easter is for me a coldly rational, magnificent moment.

Perhaps I was wrong. Easter need not be a coldly rational moment, at least not from John Updike’s perspective. Its s a monstrous, shocking moment, literally true in its screaming scientific detail; impossible but true. It is not to be toned down, rationalized, prettified. It is to be confronted and accepted, or confronted and fled. There is no compromise:

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

Christ rose from the grave, Updike says, with the same hinged thumbs and toes we ourselves have, the same valved heart we have—but with Christ it was a heart that had been pierced, a heart that had died, that withered, and then regathered new strength.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence;

Making of the event a parable

No, says Updike, it is Christ himself, body reconstituted, raised from the dead who emerges when the stone is rolled back. A real stone, the same stone which for each of us will someday eclipse our own wide light of day, just as it did for Christ.

John Updike (1932-2009) wrote this thirty-five line poem in 1960 while attending a Lutheran congregation in Marblehead, Massachusetts. He entered it in the church’s poetry competition, won its hundred-dollar prize, and gave the money back to the congregation.

![Updike on Easter (2018 Edition) 6 Dailey & Vincent - By the Mark (Live] ft. Bill & Gloria Gaither](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/Dw-uklIlQE0/hqdefault.jpg)

‘Visceral clarity’: Dailey and Vincent, ‘By the Mark,’ written by Bill and Gloria Gaither

He was twenty-eight years old and already wise enough to see, as many gospel singers do, the view from inside the cave, the end of our daylight, approaching death, “the vast rock of materiality that in the slow grinding of time will eclipse for each of us the wide light of day.”

This is visceral clarity Jamie Dailey and Darrin Vincent deal out in “By the Mark,” a new gospel song.

More than fifty years have passed since Updike wrote his poem, and still it drives our thoughts. It makes us decide.This is poetry in action. Christ is for real, or he isn’t. We must decide.

—Excerpt from Politics, Faith, Love: A Judge’s Notes on Things That Matter by Judge Bill Swann (Balboa Press, 2017)

***

Easter Faith

By Richard Ward

A short story by John Updike comes to mind this season. It’s called “Short Easter” and focuses on a character named “Fogel.” Fogel is nearing retirement age and through the years, he has made a long journey away from Easter faith. Easter and all that it represents has lost its grip on him. Easter, he muses, has always been a holiday that lacked real impact. In contrast with Christmas or Thanksgiving, Easter for him always came across as being rather flat.

The story takes place on an Easter Sunday afternoon. Fogel is tired and sore from the work his wife made him do in the garden. He is drowsy from the extra bloody Mary that he treated himself to at brunch. So that he is not disturbed, Fogel goes up to his son’s room to take a nap. His son is all grown up and gone so he has the room all to himself.

Sitting on the bed, he notices what his son has kept from his growing up years. The photos, moments stolen from his life in sports, yearbooks and trophies, banners hanging on the wall, letter jackets in the closet, and shot glasses stolen from exotic places. He lies down and falls into the deepest kind of sleep.

Then he starts to dream. He dreams of his parents—long dead—and in the dream his parents hover over him. They are saying something but he can’t quite make it out. Whatever it is startles him awake and he sits up in bed.

It’s dark. He is stiff from lying in a fetal position. For a moment he forgets where he is and he is frightened. What was that strange sense of terror that cut through him like a knife, he wonders?

Everything was still in place, John Updike tells us, but something was immensely missing.

What’s “immensely missing” from Fogel’s life and from many of our own Easter celebrations is a sense of Mystery. It is so easy to remove the terror from the story to fill it with sweet smelling bouquets of exclamation points. What would a Jesus on the other side of death say to us about our own death-dealing ways in the world? An “Easter-lite” that looks like a bunny hopping across the lawn will soon lose its grip when it faces Death. When Jesus does appear to his disciples, their joy is interlaced with terror.

Just as we remember “Short Easter” during this season, it is well to remember the last one of Updike’s “Seven Stanzas For Easter”:

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,

for our own convenience, our own sense of beauty,

lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour, we are

embarrassed by the miracle,

and crushed by remonstrance.

Posted at Phillips Seminary, April 20, 2011

Painting by Oswaldo Guayasamín (July 6, 1919 – March 10, 1999, an Ecuadorian master painter and sculptor of Quechua and Mestizo heritage.