John McCutcheon: ‘If he touches you once he takes you, and what he takes he keeps hold of…’

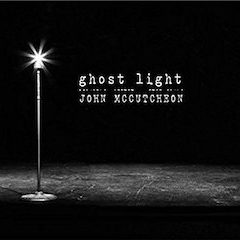

GHOST LIGHT

John McCutcheon

Appalsongs

Thirty-nine albums. Think about that. In a recording career dating back to 1975, John McCutcheon still hasn’t sung it all. Here in 2018, with Ghost Light, he’s rarely been better. Well, storytellers don’t run out of stories to tell, but maybe the important point about McCutcheon’s art is that he hasn’t run out of hope. There are generational shifts noted in Ghost Light, an acceptance of time moving on and things changing, not always for the better, but also of lives still being lived day to day, of the same tensions animating these days as they did in his younger years, and that ol’ wheel keeps on rolling. He says as much in the sprightly rhythms of the album opener, “Perfect Day,” spiced as it is with Stuart Duncan’s cheery, back-country fiddling and McCutcheon’s warm, bouncy vocal declaring, “It is a perfect night, it was a perfect day/I got to work, I got to write, I got to play/and I got to sweat and I really got to say/be hard to beat but I’d like to repeat this perfect day.” Let’s think about living, in other words.

‘This Road,’ John McCutcheon, from Ghost Light

‘Burley Coulter at the Bank,’ John McCutcheon, from Ghost Light

Like many McCutcheon albums so attuned to chronicling the little dramas playing out in everyday life, in shadows and in light, Ghost Light unfolds as a musical kin to Sherwood Anderson’s classic nove from 1919l, Winesburg, Ohio. Witness the protagonist in the Irish-tinged ballad “She Just Dances,” who seems adrift but senses the answers she seeks lie in movement, forward motion towards an undefined goal, but a goal nonetheless, and in this way brings life to all those around her: “Where she doesn’t know what she should do/and she doesn’t know she doesn’t know/it’s not wrong, it’s not right/it’s glorious sight, this rapturous moment of utter delight/no hint of embarrassment, nothing contrite/she’s not taking notice or chances/she just dances.” Over here is “Burley Coulter at the Bank,” a struggling farmer needing a loan to “see out his year,” only to find the bank in his little farm town has been swallowed up by a larger bank, and the personal service he was used to is now the province of decisions made by faceless bureaucrats “an ocean from here.” Over Jon Carroll’s poignant keyboard atmospherics, McCutcheon paints a portrait of utter desolation played out in chilling silence: “He looked out the window, he looked at the floor/and then he looked me straight in the eye/he pushed back his chair, walked out the door/nary a hint of goodbye.” Noting how Burley could only find worth “in neighbors and animals, seasons and signs, who knew his small place on this earth,” he reminds us what this vanishing breed stands for: “He is the past made of muscle and sweat./while the future’s all zeros and ones/he is remembrance of all we forget/when the noise and the lights are all done/he is the language I don’t speak/and yet it still feels like home on my tongue.” The climax will nail your head to the wall and leave it hanging there like an empty paper bag. And then there’s “This Road,” a jaunty bluegrass toe-tapper commencing innocuously in 1949 on a well-traveled dirt road winding “from here to God knows where.” Our narrator watches as over time the dirt road becomes a gravel road with tar, then asphalt and concrete, and how all this so-called progress led the environmental pillaging as profiteers moved in to denude the landscape, leaving behind “an acreage of loneliness, steel and gasoline”—he even sees it leaving his aging self behind, as a younger generation in a fast-paced world takes over, going God knows where.

In the gospel strains of “Me and Jesus,” McCutcheon speculates on the nature of a friendship he might have shared with the Son of God (“who wouldn’t want a pal who could turn water into wine?”), then turns it around into speculation on what Jesus would think of the world today with “the money changers in charge again.” Against the guitar-and-fiddle backdrop of “The Machine,” a 92-year-old WWII veteran watches the torches of Charlottesville march by and cannot contain his fury: “Now seventy years later, here they are again/none of them was even born but I was present when we liberated Birkenau/I still see every face/I didn’t fight the Nazis to allow them in this place.” The song title refers to the slogan Woody Guthrie emblazoned on his guitar: This Machine Kills Fascists. Concludes McCutcheon’s veteran: “We must be the machine.”

‘The Machine,’ John McCutcheon, from Ghost Light

‘When My Fight for Life is Over,’ John McCutcheon with lyrics partly written by Woody Guthrie. Harmony vocals by Kathy Mattea and Tim O’Brien. Stuart Ducan, fiddle; Rickie Simpkins, mandolin; Richard Bailey, banjo. From Ghost Light.

It’s fitting McCutcheon should find some uncompleted Woody Guthrie verses and put the final touches on them for this album. Enlisting Duncan on fiddle, Rickie Simpkins on mandolin and Richard Bailey on banjo, adding harmony vocalists Kathy Mattea and Tim O’Brien, “When My Fight for Life is Over” is a buoyant bluegrass celebration of a spirit soaring, unbowed by all manner of corrosive behavior it fought against in its earthly days: “When my fight for life is over and my tongue is finally still/may the breezes bear my ashes like they did for old Joe Hill/and my sweat will grease the engines that make this whole thing run/and the ruling class can kiss my ass, ‘cause I’ve had a heap of fun.”

In the end, the literary critic and political activist Irving Howe, in his introduction to Winesburg, Ohio, references the poet Algernon Swinburne’s sacred debt to the words of Elizabethan playwright John Ford in admitting an identical haunting effect Howe experienced in reading Sherwood Anderson’s words. To this I submit the same ineffable quality is abundant in John McCutcheon’s music, here on Ghost Light and lo these many years. To wit: “If he touches you once he takes you, and what he takes he keeps hold of; his work becomes part of your thought and parcel of your spiritual furniture forever.”