vonn

vonn

In the late 1980s, U.S. audiences met an odd musical group from Finland: the Leningrad Cowboys, stars of a deadpan-comic, not-quite-documentary, road-trip film called Leningrad Cowboys Go America.

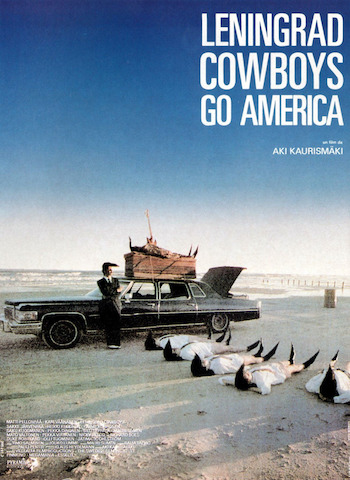

Once you got past the name, two other things made the Cowboys stand out–most immediately, their look. They sported black suits, white shirts, ties, and dark shades… but they were no Russo-Scandinavian Blues Brothers. Rather, their hair was pompadoured forward, to stiff points protruding about a foot from their foreheads, and on their feet they wore ridiculously elongated “winklepicker” shoes, curled at the toes. (A poster for the film shows members of the band lying on their backs side-by-side on a beach, sans pants and jackets; in those hairdos and shoes they resemble a series of empty parenthetical expressions–not a bad metaphor for the film’s plot, actually.)

The second and more genuinely odd thing about them: their music. Back in their native Finland, their preferred genre had been a peculiar mashup of polka, Scandinavian folk and wild Cossack dance tunes. They weren’t particularly good at it, though, and so they’d come to the U.S., where, their manager had been told, the gullible public would accept anything. Their pop-culture schooling continued here, when a New York promoter told them they needed to drop the awful polka shtick and play rock ‘n’ roll; for their first official gig, he sent the band across the continent, in a broken-down Cadillac, to play at a wedding in Mexico. En route, they performed one-night stands in dive bars and seedy pit stops, adopting whatever they imagined to be the local musical style: “Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay” in Memphis, “Born to Be Wild” at a biker bar in Texas, and so on.

‘Those Were The Days,’ The Leningrad Cowboys’ distinctive send-up of the Paul McCartney-produced hit by Mary Hopkin, a #1 U.K. single, #2 U.S. single in 1968

Most notably, the further they got from their roots and their own native “genre,” such as it was, the better their performances became…

If you’ve seen the film, and only later learned of the musical genre most concisely termed “international Americana,” you might imagine the arc of the film’s storyline run in reverse: American roots music and its descendant genres, journeying across borders for adoption by artists whose native language may or may not be English, and whose native instruments may or may not be guitars, fiddles, harmonicas, and bass.

And what, you may wonder, would such a thing sound like? What would the songs say?

***

Before proceeding too much further, some background on “Americana” music in general might help focus the search for its international form. The term was born in the early to mid-1990s of frustration among certain artists and other music professionals (producers, radio DJs and retailers). The problem, as they saw it: too-rigid categories–or, for that matter, too-vague ones.

Most of the artists involved were generally regarded as country performers, if anything. The arrangements might feature a single guitarist and vocalist, or they might include a full-blown band; the songs might deal with many of the tropes familiar to pop- and classic-country audiences and critics. These superficial elements weren’t the “problem,” really. What made these artists not quite fit under the country umbrella were the idiosyncrasies: the melodies, arrangements and lyrics wandered into areas where the large country-music audiences didn’t feel comfortable. The artists themselves resisted donning the straitjackets required by the big country recording labels. (Similar nonconformist traits had driven the separation of punk from mainstream rock, a couple decades earlier.)

Which is all well and good in the abstract. But if you’re a professional musician, you want your music heard by audiences. How will everybody “out there” even find you in the first place? Can you rely on word of mouth? Once they’ve found you, will they come back for more if you weren’t what they expected? Can you make a living from writing and playing unclassifiable music? Must you resign yourself to a life of touring small venues, where the audience is present for some other reason–drinking, dancing, darts, whatever–and don’t even care who’s onstage? The answer, for both good and ill, is genres. The music industry establishes genres via trade associations, publications like Billboard, and other such institutions. But in the mid-’90s, admission through those doors had become way too expensive for many independent artists–expensive both monetarily and spiritually. You had to offer some big hits to get inside… but you can’t craft big hits from songs written for small audiences, no matter how satisfying the music might be in its own terms.

‘Tulare Dust/They’re Tearing the Labor Camps Down,’ Tom Russell, from Tulare Dust: A Songwriters’ Tribute to Merle Haggard

So there had been some pressure bubbling beneath the surface by the time the first radio-industry publication, The Gavin Report, came out with an Americana chart in January, 1995. Here’s how they characterized the new genre for readers:

From the dust of what was once heralded as progressive, renegade, eclectic, Western Beat or alternative, it all comes down to American roots music steeped with a history, heritage and ongoing influence. Stylistically it’s got a musical bone called country. It’s steel guitars, mandolins and acoustics rather than synthesizers and line dance mixes.

Topping that first chart’s performers was a Merle Haggard tribute album called Tulare Dust, followed by Nanci Griffith and Mary Chapin Carpenter… But then the standard categories started to wobble a bit. Greg Brown–you mean the folk singer? Nick Lowe–okay, that guy who’d married into the Carter-Cash family but, hey, wasn’t he a rock musician? Gavin’s Americana editor, Rob Bleetstein, said in his “Inside Americana” introduction that the list was

…a nice healthy mix of indies, majors, knowns and soon to be knowns. Tulare Dust is certainly proving to be the album that defines the [Americana] format, and who could argue. A big thanks to all for making week one get up and running ahead of schedule. This is exit 0 on what will hopefully be an endless highway, and I hope y’all plan to make it to N’awlins, for there will be plenty of Americana fireworks.

Note the little stylistic touches added, maybe, to soften the shock of the unfamiliar: the genuflection to the Haggard tribute, a nod to the debut album of soon-to-be-Americana-icon Steve Earle (Exit 0), a reference to a lonesome road, a y’all and a N’awlins, and a hint of red-white-and-blue festivities to come. Because this might be a new genre, but nobody wanted to alienate the potential audience before the genre had a chance to grow.

***

What, you may wonder, was the state of the music industry in the U.S. at the time; particularly, how might that translate to the international scene? For a quick answer, consider some more recent statistics for another country where the industry faces similar creative frustration and marketing pressures. In the U.S., data on the music industry comes from music publishing, licensing and marketing organizations like the RIAA, ASCAP and BMI. The Australian counterpart is an umbrella organization called APRA/AMCOS. (It’s an acronym for the Australasian Performing Right Association/Australasian Mechanical Copyright Owners Society–no wonder it’s almost never spelled out! Note, though, that it’s not specifically Australian, but Australasian: membership and coverage includes both Australia and New Zealand.)

Why focus on Australia’s profile here? As it happens, the Australian spinoff of the U.S.’s own Americana Music Association–the AMA-Australia–was just formed in fall, 2016. By looking at the statistics for Australasian music generally in, say, 2014, we can get a sense of the justification for a group to focus on Americana music in that region, and maybe others.

Here are the counts, from 2014, of performers who identified themselves using the APRA/AMCOS list of musical genres. This count includes all performers in Australia and New Zealand, whether or not they reported any earnings for the year. (Genres in boldface are those from which Americana performers in the U.S. would typically be drawn, if no Americana genre were available.)

| Genre | Number of Performers | % of Total |

| Pop/Rock | 59,286 | 28.34% |

| Alternative | 27,746 | 7.73% |

| Blues & Roots | 15,360 | 4.63% |

| Electronica | 14,387 | 4.55% |

| Country | 13,994 | 4.64% |

| Urban | 11,924 | 4.15% |

| Dance/Techno | 10,318 | 3.74% |

| Jazz | 10,273 | 3.87% |

| Metal | 9,410 | 3.69% |

| Folk | 8,059 | 3.28% |

| Screen* | 5,974 | 2.51% |

| Classical | 5,227 | 2.26% |

| World | 5,130 | 2.27% |

| New Age | 5,125 | 2.32% |

| Gospel | 3,957 | 1.83% |

| Children’s | 3,047 | 1.44% |

*The count of performers under the “Screen” genre comes from the APRA itself, not performers. Presumably this is because screen music’s genre varies according to a film/TV show’s soundtrack: the term thus describes not a standard “genre,” but the medium in which the music is presented,

We can observe a few things about this breakdown, especially in the absence of an Americana genre. Most obviously, if a performer might have self-identified as an “Americana” or even a “singer/songwriter” performer, they didn’t have the option: the list presented by the industry included no such terms. Instead, no matter how little they might have felt they belonged to a more accurate classification of their music, if they wanted audience and press attention, they had to pick one of the standard ones.

Less obviously: the total of the percentages comes to only about 81percent. The missing 19 percent–over 39,000 performers–were simply “miscellaneous” others. In that group, and scattered among the other standard genres, lay the opportunity for an “Australian Americana” category.

***

But let’s get out of the numbers thicket, and get into some actual music.

The best way to get a general feel for a given culture, as quickly as possible? Eavesdrop on an informal gathering of its participants. The technique works well, albeit metaphorically (and much less creepily), when applied to cultural artifacts instead of people: curated art exhibits from multiple artists and sculptors; anthologies of essays, poetry, and/or stories by multiple authors; and of course playlists of music by multiple performers. Conveniently, Americana-by-non-Americans already has such an ongoing playlist: The International Americana Music Show (TIAMS for short), a podcast launched in 2014 and still curated by Michael Park–himself a native Scot, now living in the U.S. Besides its own site, the podcast is also currently carried by around three dozen American radio stations, and is available online from the MixCloud streaming/aggregator site.

Each weekly episode of TIAMS features about an hour’s worth of music by artists from around the world: Japanese-Americans rub elbows with New Zealanders, Finns with Dutch, Northern Irish with Canadians and Australians, Danes with Scots, Welshmen with Swedes, Japanese with Brazilians… and they’re all performing in styles classifiable as “Americana.” Via email, Park discussed how he defines the term.

“I would say what makes [these artists’] work Americana,” he said, “is the fact that it is derived from what people in America would recognize as music that is believed/accepted to have originated and flourished here, be it from Appalachia, Alabama, Greenwich Village or Red Dirt country.”

He went on to specify that TIAMS itself is targeted at an English-speaking audience; thus, the songs featured there are performed almost exclusively in English. But, he added, “if you adopt the ‘style’ of Bob Dylan, or Woody Guthrie, or Townes Van Zandt, or have an alt.country sound, etc., then you could sing in any language and still call it Americana. I have played songs which include verses in other languages (Inuktitut and Swedish).” Park also draws a line between Americana and certain other related genres, like folk: “I can think of an Inuit band (The Jerry Cans) whose music is mostly indigenous folk music, but some of their songs have a more ‘American’ feel to them, and I can think of an English duo (Josienne Clarke and Ben Walker) who used to be a very traditional folk duo but whose latest album has a more expansive sound and as a consequence I have felt able to play tracks from it on the show.”

‘Dark Turn of Mind,’ Josienne Clarke and Ben Walker, from their latest album, Overnight

Park has been appreciating Americana since before the term began to describe the genre. He’d been a longtime aficionado of roots music, while working principally in public relations and general-purpose journalism. But he’d worked in radio in college, in London, and never lost his love for the medium. When he discovered the Internet radio station called Wrecking Ball Radio shortly after it started up in 2011, he realized the opportunity to get back into the field. The genesis for what later became TIAMS was the show he pitched to Wrecking Ball Radio’s founder, Jayson Tanner: Border Crossing.

Clark says of his first show, in 2013, “I played thirteen artists: six Brits, one Aussie, one New Zealander, one Canadian, two Swedish artists and two Irish artists. At that point I really had no idea just how big Americana was outside of America. But each week, needing to find 10-13 songs for a show, I kept Googling, I kept visiting music websites in other countries, I kept listening to other radio shows around the world–and I never stopped finding new artists who would tag their music ‘roots’ or ‘Americana.'”

***

As Park indicated, by far most of the “non-American Americana” music comes from countries whose principal language is English. The percentage of the total performed by artists from such countries (according to an unscientific survey of over 450 songs) works out to nearly 70 percent. (Excluding Canada, the rest–the British Isles, Australia, etc.–account for about 50 percent of the total.) Scandinavia (Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden) constitutes another 10 percent. Soloists and bands whose work might be considered Americana are playing, apparently, in every country on Earth.

But numbers don’t say much about the subjective questions raised by the phrase “non-American Americana.” For those questions, we need to turn to those most likely to advocate (or not) the use of the “Americana” genre label in the first place. What do the artists themselves experience as Americana? And what do their audiences make of it?

***

Lillly Drumeva: ‘I don’t think of myself as an Americana artist. I play country and bluegrass music with a European touch. I am influenced also by Bulgarian and Irish folk music.’

Part 2: From the Artists’ POV: ‘We’re Just Making Music We Like’

To get a handle on “international Americana” from the artists’ point of view, you could do worse than begin, say, with Lilly Drumeva–not that she herself necessarily accepts the label.

The other members of her band, Lilly of the West, came from a jazz background, and first encountered country/bluegrass music in 1990. The last of the old Soviet bloc was collapsing, in Bulgaria as elsewhere in Eastern Europe, and the American Embassy there arranged for bluegrass star Tim O’Brien to appear in concert, and so what became Lilly of the West had their first encounter with the sound.

Drumeva herself, though, first crossed paths with the genre a couple years later, while a college student studying economics, in Vienna. There she attended a concert by Emmylou Harris and (as she told Western Kentucky Radio in 2013), “I got hooked.” In 1996, after immersing herself in more concerts and recordings, she formed Lilly of the West back home in Bulgaria. Within two years, the band was performing at the inaugural European World of Bluegrass festival (EWOB) in the Netherlands, where they outright won the “Europe’s Best Bluegrass Band” award. They’ve been performing and recording around the world since. Meanwhile, Drumeva herself has gone on to work with the BBC as a music journalist and presenter, to formally study bluegrass as a 2013 Fullbright Scholar, and to perform as a solo artist.

‘When the Roses Bloom Again,’ Lilly Drumeva

So Drumeva, as much as anyone, can speak to the subject of American roots music in Europe: she’s been part of the phenomenon in central Europe since before the term “Americana” was first introduced, even in the US. So, yes, color her skeptical about the need for the term at all, certainly as a term for her music.

“No,” she said via email, “I don’t think of myself as an Americana artist. I play country and bluegrass music with a European touch. I am influenced also by Bulgarian and Irish folk music.”

Which, of course, begs the question of what she recognizes as Americana in the first place.

She acknowledges that Americana is “real country music, about real problems, stories and social issues.” But it’s “more authentic and honest than the mainstream country music. It often has darker lyrics and melodies. Songs are not as polished as the ones on the charts.

“The focus is on the lyrics,” she says, and adds (recalling those “darker lyrics and melodies”): “It has a touch of depression.”

Depression, yes: for instance, Lilly of the West’s contribution to the official recording of that 1998 EWOB festival was not a traditional number, but a haunting, tradition-drenched cover of Gillian Welch’s plaintive signature song, “Orphan Girl.” Welch, of course, is an artist squarely in the center of any Venn diagram purporting to represent the Americana genre. And yet, again, Drumeva does not consider–has never considered–herself (or the band) an Americana act.

You may already sense the tendency of the genre’s definition to slither away out of reach as soon as you approach it. But the artists surveyed for this piece did find some common elements–most obviously, the sound of Americana.

‘Orphan Girl,’ Lilly of the West’s haunting cover of the Gillian Welch tune, first released on the 1998 European World of Bluegrass (EWOB) collection

From Eric John Kaiser, a self-styled “Parisian Americana” native of France, now living in the U.S. Pacific Northwest: “I like that authentic Americana sound (with touches of lap steel, blues guitar riffs and grooves).”

Bregje Sanne Lacourt, an Americana-influenced singer-songwriter in the Netherlands: “You can never smooth things up with Americana the way they do with pop music. I’d rather hear authentic sounds like organ, trumpets, banjo, guitar, double bass.”

Mari Sandvær Kreken, with the Norwegian Americana/bluegrass band Darling West: “It often involves harmony singing, some acoustic instruments, more thoughtful and meaningful lyrics than an average pop song and a rougher sound than modern country.”

Joe Troop, a mainly bluegrass, Americana-tinged artist and teacher who’s now been living in Buenos Aires for several years: “I think ‘folk’ music is mostly strumming a guitar and singing, like Bob Dylan. Nowadays it seems like folk played on anything other than just an acoustic guitar is labeled as Americana.”

‘Life Underground,’ by Eric John Kaiser, a self-styled ‘Parisian Americana’ native of France, now living in Portland, Oregon

***

Behind Troop’s use of the word label lies an important truth: “Americana” may or may not be adopted by artists to describe their own work, but outsiders (audiences, producers, music journalists, and retailers) can use it to signify certain not-quite-country, not-quite-folk, not-quite-blues-or-bluegrass artists, songs, and performances. The word itself certainly existed and was even common prior to the 1990s, even going back to the 19th century. But it hadn’t been applied specifically to music yet. Instead, “Americana” described folk art, arts and crafts, furniture and fabrics–generally, physical products manufactured by individuals, reflecting stylistic and thematic quirks which you couldn’t find in their mass-produced counterparts.

The appeal of such idiosyncratic, often rough-hewn elements isn’t limited to products made in America. In fact, a habit of including “flaws” is often codified in traditions and sacred texts around the world; you hear stories–some apocryphal, some well documented–of Native American rugs and pottery, geometrical Amish artwork, and architecture and other structural disciplines with Islamic roots which share this feature. In many such traditions, perfection is considered almost a form of blasphemy: presuming to duplicate the work of gods.

The de-emphasis on polish draws many Americana-in-America musicians to the genre. And it seems to appeal to international Americana performers, too.

***

The band called Pirates Canoe has carved out some kind of “Americana” niche for themselves in Japan, although their songs are almost exclusively written and sung in English; their members are all Japanese or Japanese-American. So do Japanese audiences recognize “Americana” when they encounter it?

‘Faith in Me,’ Pirates Canoe. Of the term ‘Americana,’ lead singer Elizabeth Etta says: ‘In the end, we are just making music we like.’

“Not so much,” says Elizabeth Etta, Pirates Canoe’s lead vocalist and principal songwriter. “Compared to when we first started playing eight years ago, there seem to be more people who know the term ‘Americana,’ but it is still pretty unknown.” So what then does it mean to be an “Americana” act at all? “I think of it as a term that was born out of necessity,” Etta says. “New musicians and bands were starting to make music that defies the conventional boundaries of ‘country,’ ‘bluegrass,’ ‘blues,’ ‘folk,’ etc. They were combining their different influences and creating something new, and people adopted the term ‘Americana’ to describe this new music.”

Born out of necessity: that’s a key notion–the requirement to call it something at all is external. “It seems to be a convenient enough label for the music we make,” says Etta, “so we use it and don’t mind when others do… But our influences are actually pretty varied, including Broadway musicals, funk, pop, even classical. In the end, we are just making music we like.”

***

Well, then, is the English language a required element of Americana?

Granted, most international Americana artists so labeled do sing in English: it’s their native tongue, or at least common in their homeland, whether they come from the British Isles, Canada, Australia, or the like.

But at least theoretically, must lyrics to an Americana song be written and sung in English?

Kaiser, the “Parisian Americana” artist, continues to sing in French although living in Portland, Oregon. Undeniably, on the one hand, he grew up in France. He grants that he adopted the musical stylings of what’s called “Americana”: “Most of the music I use to carry my lyrics,” he says, “is influenced by American roots music (like blues, rock or acoustic folk music).”

Of course, France has always been wary of broad, rapid adoption of American culture. Even so, there’s no getting around the American influence on music. “The Americanization of French culture,” says Kaiser, often comes up in his discussions with students. “Traditional French music, from artists like Edith Piaf, Jacques Brel, Georges Brassens, comes more from a cabaret tradition. Lyrics in that [cabaret] artform are very important.” World Wars I and II and subsequent years may have brought jazz, rock, hip-hop, and other characteristically “American” musical forms to France, inescapably. But, he says, “most of the music sold in France today is still music that is sung in French. People want to understand the lyrics.”

Yes: people want to understand the lyrics. That presents questions for Joe Troop down in Argentina, too, who’s reversed Kaiser’s musical path, taking his music from America to another country.

‘Uncle Pen,’ by Che Apalache (translation: my Appalachian homebody), an international bluegrass quartet comprised of an American (Joe Troop), a Mexican and two Argentines, based in Buenos Aires, cover the Bill Monroe classic

“I honestly think ‘Americana’ as a term describes stuff sung in English,” says Troop. “With my band Che Apalache I’ve begun to compose in Spanish, but mostly over musical forms derived from South American music. I do most of my music in English, naturally. But since I live in South American, I guess much of my poetry is lost on my audience.

“I’ve thought about this a lot over the years,” Troop continues, “and since I’m in Argentina for the long haul, I’ve recently started to compose in Spanish. After all these years, I feel I’ve earned the right to be a legit singer-songwriter in my second language.”

***

Emily Barker has spent her whole life immersed in the English language. Native to Australia, relocated to England in her 20s, and most recently in Nashville, she’s heard the language spoken and sung in all kinds of settings and accents. And naturally enough, her lyrics are all in English. (Her song “Nostalgia” won several awards as the theme for the BBC/Kenneth Branagh version of the Swedish crime drama Wallander; arguably, then, she’s even familiar with hearing English against a Scandinavian backdrop.) For her, “I think that even if the language wasn’t English, a song could still identify as ‘Americana.’ It’s about the type of song it is, the melody, the chords, and the production.”

The Norwegian bluegrass/Americana trio Darling West sings all their songs in English. But as their lead vocalist Mari Sandvær Kreken says, this was simply an artistic choice. The English language might be the one most readily associated with these genres, but not a requirement:

“[At least] in terms of bluegrass,” she says, “I think the sound of the instruments defines the genre, and therefore it does not need English lyrics. There are Norwegian bands that play bluegrass and play in Norwegian.” She points to a recent “Norwegicana” playlist on the Tidal streaming service, which mixed both English- and Norwegian-language tunes.

‘A Nobody’s Song,’ by the Norwegian bluegrass/Americana trio Darling West, from the group 2016 album, Vinyl and Heartache

(Sandvær Kreken notes, though, that Scandinavia might not be a good example of where to find an opposing point of view on the language question. “We learn English in school, and so we can relate to the lyrics as well… The English language is such a big part of our culture, it feels very natural.” For example, even with all the American TV shown in Scandinavia, there’s no dubbing or subtitling.)

***

So okay. If not America, nor the English language, what’s the common thread that says Americana?

“For me,” says Emily Barker, “Americana music is rooted in American types of music such as bluegrass, old country, American folk, blues and soul. It might only marginally draw on influences from these longer established genres, or it might cross between them. For me it’s also about the quality of songwriting and storytelling. It’s about depth, soul and not using cliches like those that exist within radio-friendly country music. It’s individual, personal and from the heart.”

(Individual. Personal. From the heart. See? Sounds familiar. Handmade. Artisanal. Idiosyncratic… just like the furniture crafted by adz, chisel and paintbrush instead of machines.)

I asked her, then: if it’s too hard to pin “Americana” down, is there any value in the term at all? “I like not being easily definable. I think it gives me creative license to experiment as I please. After years of being too folk for pop, too country for folk, too pop for alt, etc., it feels quite good to have found a banner to hold onto when needed.”

‘Sister Goodbye,’ by Australian Emily Barker. ‘(Americana) is about depth, soul and not using cliches like those that exist within radio-friendly country music. It’s individual, personal and from the heart.’

Striking, no? While Barker embraces the Americana label, she does so because it frees her to be none of those other things: to be, in short, unclassifiable.

Eric John Kaiser agrees: musicians themselves don’t have to self-identify with Americana in order to be Americana performers. As he points out, the original practitioners of what’s now called “Americana” barely thought of themselves as performers at all.

“The U.S. is the only country in the world,” Kaiser says, “that has mixed African-influenced music (blues and jazz, unique American art forms) with folk and storytelling traditions coming from Ireland and England and maybe Germany. The music ‘imported’ from the slaves coming from Africa over the years has mixed itself with music coming from the Appalachians. It has evolved even more as people traveled up the Mississippi River looking for work.”

So regardless how it’s labeled, no matter the language, does the audience even need to understand the lyrics at all?

Pirates Canoe’s Elizabeth Etta says no. On the contrary, “Performing English music for a Japanese audience has its own advantages and challenges. For example, it gives us a novelty factor, but because we can’t keep the audience’s attention with the lyrics we have to be creative in telling the story (conveying the song) in different ways, like the arrangements.”

Now turn the question around: if you don’t recognize the language at all, could you tell it was Americana? Not everyone would take it that far. Says Bregje Sanne Lacourt: “If I hear a song with the sound of Americana but in a different language I would label it as folk. So the English language does actually make a difference for me.” Even Etta, who accepts that Pirates Canoe’s own audience may not understand English-language lyrics, said she’d have to hear an example in another language before deciding.

The question hangs in the air, unanswered for now.

***

Although a West Virginia native, “prairie troubadour” Scott Cook has been touring the world, especially Canada, for many years. He may perform exclusively solo or with his small band, The Second Chances; he may simply sit onstage or in a studio and play an acoustic guitar while singing in his grainy, unaffected voice; his music may deal with (as Lilly Drumeva says) “real problems, stories and social issues.”

But with all that, he doesn’t think of himself as an Americana performer.

“I like the term ‘folksinger’ just fine,” says Cook. He clarifies: “‘Folk’ is often just taken to mean singer-songwriter music played on acoustic instruments. But I tend to think of folk music as having some connection to the modern folk tradition, the lineage of Woody Guthrie, and in some sense being ‘people’s music’ rather than commercial music.

“I think of myself as coming from Woody’s line, which is an older and less geographically-limited line than the modern term ‘Americana’ tends to suggest.”

‘Further Down the Line,’ Scott Cook. ‘I think of myself as coming from Woody’s line, which is an older and less geographically-limited line than the modern term ‘Americana’ tends to suggest.’

Cook seems almost wistful not just about folk music, but also about the popular conflation of “roots music” with “Americana.” “Classic reggae certainly falls under the banner of roots music, but isn’t called Americana. Appalachian fiddle tunes,” he continues, “aren’t so far from Acadian fiddle tunes, are they? And Acadian music has long history in the Midwest as well. Roots music, to me, just means music that’s coming from an old tradition, and paying some respect to an idiom, even if it’s not slavishly imitating that idiom.”

All of which reverberates with a point Joe Troop made: “I do not think roots and Americana are synonymous,” he said. “Roots music has just that: roots in a musical tradition. Many ‘Americana’ artists are not proficient at any traditional genre. I would say that ‘Americana’ basically means folk music with airs of traditional music, regardless of whether its practitioners are proficient traditional musicians. I feel that to play legitimate music one must have a musical foundation.”

That’s why Troop doesn’t readily self-identify as an Americana artist. “Bluegrass,” he said, “is my teacher, my home base. A lot of rock musicians have no home base. They can only play what they play in their bands. This happens with Americana also.”

***

Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Cat’s Cradle introduced readers to a fictional Caribbean-based religion called Bokononism. The religion’s tenets were described in invented terms that sounded mysterious, but turned out on closer examination to be simple. Says Wikipedia: “Bokononism is based on the concept of foma, which are defined as harmless untruths. A foundation of Bokononism is that the religion, including its texts, is formed entirely of lies; however, one who believes and adheres to these lies will have peace of mind, and perhaps live a good life. The primary tenet of Bokononism is to ‘Live by the foma that make you brave and kind and healthy and happy.'”

‘Prisionero,’ Che Apalache. Band leader Joe Troop doesn’t readily self-identify as an American artist. ‘Bluegrass,’ he says, ‘is my teacher, my home base. A lot of rock musicians have no home base. They can only play what they play in their bands. This happens with Americana also.’

Consider art-genre concepts like “performance art,” “speculative fiction” (instead of “science fiction and fantasy”), and, yes, “Americana.” Are these examples of Vonnegut’s foma? More broadly, is a community built around such terms an example of Vonnegut’s granfalloon–“a seeming team that was [actually] meaningless in terms of the ways God gets things done”? Do labels like these actually communicate anything useful?

Every artist contacted for this piece has been at some point identified as “Americana” in style. They embraced the label, or shrugged it off on any number of grounds; to use it at all represents a conscious but arbitrary decision to use it–one can make that decision, or make another, or make no decision at all.

But for what “international Americana” musicians themselves hope to accomplish, it seems to make no difference at all. To repeat what Elizabeth Etta said: “We’re just making music we like.”