https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ui5CZvjJI8U

Director: Douglas Sirk

Producer: Ross Hunter

Screenplay: Peg Fenwick; Edna L. Lee and Harry Lee (story)

Music: Frank Skinner

Cinematography: Russell Metty (Director of Photography)

Art Direction: Russell A. Gausman; Julia Heron (set decorations)

Film Editing: Frank Gross, Fred Baratta (uncredited)

CAST

(actor-character)

Jane Wyman (Cary Scott)

Rock Hudson (Ron Kirby)

Agnes Moorehead (Sara Warren)

Conrad Nagel (Harvey)

Virginia Grey (Alida Anderson)

Gloria Talbot (Kay Scott)

William Reynolds (Ned Scott)

Charles Drake (Mick Anderson)

Hayden Rorke (Dr. Dan Hennessy)

Jacqueline deWitt (Mona Plash)

Leigh Snowden (Jo-Ann Grisby)

Donald Curtis (Howard Hoffer)

Alex Gerry (George Warren)

Nestor Paiva (Manuel)

Tol Avery (Tom Allenby)

Merry Anders (Marry Ann)

***

‘Beautiful and affecting, right on the surface…’

Largely dismissed as “women’s pictures” upon their initial release, Douglas Sirk’s late output—starting roughly with 1954’s Magnificent Obsession and continuing through his final feature, 1959’s Imitation of Life—have long since been reclaimed. Critics and cinephiles argue, very persuasively, that Sirk’s direction of these apparent soap operas is subtly subversive in a way that audiences of the day mostly failed to notice. So many astute reassessments have been written over the years, however, that there’s now a real danger of discarding the trees in favor of the forest, especially when it comes to first-time viewers who’ve done their homework. Sure, one can gain a greater appreciation of All That Heaven Allows, by looking beyond its lushly melodramatic surface. But the film also works magnificently as a lush melodrama, provided that one doesn’t snootily reject that genre out of hand.

Doing so would be rather ironic, given the movie’s subject. A few years after the death of her husband, well-off widow Cary (Jane Wyman) hasn’t given up on the idea of romantic love, despite the entreaties of a respectable older gentleman (Conrad Nagel) that she marry him for the sake of bland companionship. When she falls in love with her gardener, Ron (Rock Hudson), scandal ensues, though it’s not always clear whether Cary’s wealthy and sophisticated friends are more shocked by Ron’s lowly profession or by the fact that he’s much younger than she is. (Hudson was only eight years Wyman’s junior, but the film seems to imply a significantly larger age gap.) In particular, Cary’s adult children, Ned (William Reynolds) and Kay (Gloria Talbott), find the idea of Ron as their stepfather insupportable, with Ned going so far as to suggest that he’ll disown his mother if she goes through with it. Surely Cary should choose propriety over passion and be content to spend her twilight years alone with the brand-new TV set her kids have bought her?

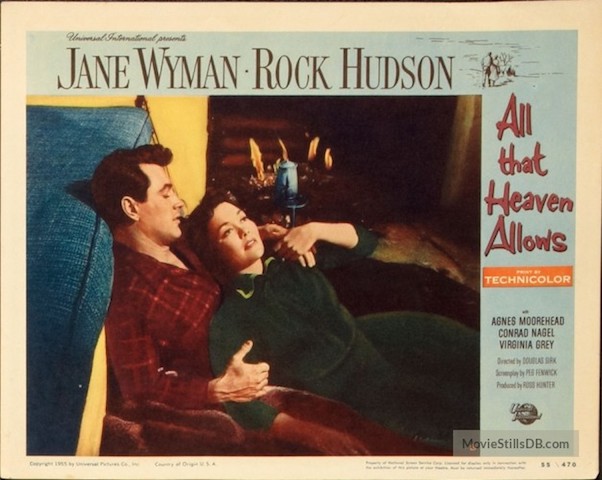

Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman in the first scene from Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows

To a contemporary audience, the hysterical outrage over Cary daring to fall for—gasp!—a gardener plays a little over the top, especially since that gardener is embodied by the unfailingly dapper Rock Hudson. Once this scenario has been accepted at face value, All That Heaven Allows requires no sly subtext to stir the emotions (though that subtext is there for those willing to seek it out). Wyman’s face alone is frequently heartrending—much of her performance involves exquisite silent reactions, like the crestfallen look that Cary struggles to hide when her older suitor suggests that she can’t possibly still be seeking torrid romance at her age. Hudson’s typically stolid performance is more problematic (and the film features a few moments that play as camp now that his homosexuality is common knowledge), but he gives Ron an unshakable sense of rectitude that serves the material well, unfashionable though it is today.

The set of All That Heaven Allows later became the bucolic suburban neighborhood of Leave It To Beaver

More than anything else, though, All That Heaven Allows is simply a stunning visual achievement, with Sirk employing deeply saturated color and geometrical compositions (note how often a vertical line separates Cary and Ron in the frame) to rapturous effect. Only a good 35mm print can convey the film’s full aesthetic power, but Criterion’s Blu-ray upgrade provides a reasonable facsimile of the experience—there are blue shadows here that stagger the eye, even on a TV screen. (Given the symbolic use of television in this film, however, prepare to feel guilty for watching it that way.) Interested parties can debate the meaning of the stag that features prominently in the final scene—does it represent the future return of Ron’s potency, or does Sirk mean to suggest that only by becoming a nursemaid can an older woman land a younger man? Just be sure to acknowledge first that it’s beautiful and affecting, right on the surface.

(A.V. Club, review by Mike D’Angelo, June 11, 2014)

***

Douglas Sirk: A Perspective

Douglas Sirk on the set of All That Heaven Allows with Rock Hudson, Jane Wyman and Agnes Moorhead

German filmmaker Douglas Sirk (né Hans Detlef Sierck) directed almost 40 films in a career that spanned three decades. A late bloomer known for grand, gorgeously expressive and emotional melodramas in the 1950s, he took a third of his career to hit full stride. The early movies were comedies, glossy adventure stories and war dramas. During his days working in Germany the director was heavily censored and when he escaped to the United States in 1937 he found himself stifled once again, “A director in Hollywood in my time couldn’t do what he wanted to do,” he once said. 1942’s vengeful, vehemently anti-Nazi Hitler’s Madman only really existed because it was seen as patriotic, and films Sirk made as late as 1952, like Has Anyone Seen My Gal? featuring his broad-shouldered go-to male muse Rock Hudson, were insubstantial trifles compared to his mature work. That film, lightweight comedy though it is, does still possess hints of commentary on class, status, money and the sickening desire for it all—themes Sirk would explore, and quietly explode, in his best work.

That work came between 1954 and 1959 at Universal-International Pictures, where Sirk broke through and finally found his way to his now-trademark CinemaScope–lush, dark melodramas and subversive social critiques. Emotionally swollen with desire, passion and infatuation, the pictures are lavish and sumptuous, but concealed beneath the impeccable aesthetics lies a caustic indictment of American bourgeois values. Again and again he reveled in the irony of often wealthy, privileged people longing for more, but trapped within the excess and decay of their decadent lifestyles.

Snippet of an interview with Douglas Sirk included on the Criterion Collection release of All That Heaven Allows

Rock Hudson, interviewed in 1980 on the balcony of his apartment in The Beresford in New York City, discusses working with Douglas Sirk and problems created by studio heads on the set of The Tarnished Angels

The films were largely a bust at the time, and critically reviled; they were often dismissed by the cognoscenti with the pejorative “they’re just soap operas for women.” It wasn’t until he was retroactively championed by the Cahiers du Cinema crowd for his immaculate craft and style that his artistic reputation finally gained its rightful position. “Time, if nothing else, will vindicate Douglas Sirk,” critic Andrew Sarris correctly predicted.

But the emphasis on the much-extolled radiant style and blazing Technicolor belies the inflamed full-bodied, sanguine emotions and psychological underpinnings of Sirk’s work, not to mention their captivatingly watchable qualities. While the movies were incandescently shot, the emotional substance within was just as luminous and psychologically cutting; much more than merely ostentatious and histrionic, as so many of those early critics suggested.

***

‘…will still make you cry your eyes out’

One of Sirk’s true masterpieces, All That Heaven Allows compellingly blurs the line between soap opera and high art, and in the process has become one of the few films that has matured into both a critical favorite and cult classic. All That Heaven Allows tells the story of Cary (Jane Wyman), an affluent New England widow who falls in love with her sensitive gardener Ron (Rock Hudson). Their romance, of course, upsets the local community and even Cary’s children reject her newfound happiness as unnatural. Their romance, too, is tinged with tragedy. Everything is so emotional that each sequence surpasses mere melodrama and almost encroaches on the land of hysteria–it’s exhibit A in why Sirk’s films were often labeled “women’s pictures,” and not in a complimentary way. While the film was initially panned (the notoriously crotchety Bosley Crowther gave it a withering write-up in the New York Times), time has been kind to All That Heaven Allows: it was partially remade by both Rainer Werner Fassbinder (as Ali: Fear Eats the Soul) and Todd Haynes (whose Far From Heaven is an explicit homage, down to the title); it’s been referenced by everyone from Francois Ozon to John Waters (among others); it made it into the National Film Registry in 1995; and has its very own deluxe Criterion Collection home video release. Surprisingly subversive (especially in retrospect, given Hudson’s hidden homosexuality), All That Heaven Allows is both a loving homage to fifties normalcy and a startling deconstruction of it (down to the obvious phoniness of many of its sets and props). The Sirk ethos has never been distilled so beautifully, cleanly, or heartbreakingly. Because, even as hammy and overwrought as it can sometimes seem, chances are All That Heaven Allows will still make you cry your eyes out.

(From The Playlist Staff, April, 26, 2013, IndieWire)

***

And Here to Save The Day…

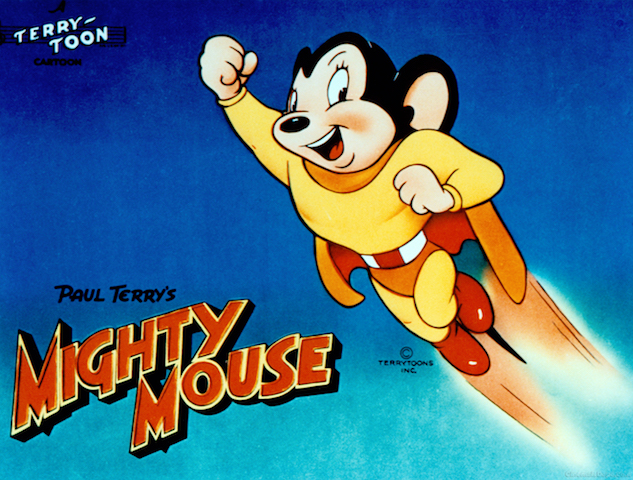

The Mouse of Tomorrow starring Super Mouse (1942)

Here’s the 1950 16mm Castle Films B&W-only home movie release of the first Super Mouse cartoon, originally released in October 1942. This was also released in a silent 8mm version. Notice that Castle put its own title cards on it, but unlike the shortened CBS versions, the cartoon is fully complete, including the opening and closing titles music, and instead of the “replaced” narration of “Mighty Mouse!” when the mouse bursts through the cheese, the original track remains intact. An original 1942 negative was obviously provided to Castle to make its own version for the home movie marketplace. Directed by Eddie Donnelly, story by John Foster, music by Philip A. Scheib. Two years later Super Mouse would become Mighty Mouse in The Wreck of the Hesperus.

The Wreck of the Hesperus starring Mighty Mouse (1944)

The first appearance of Mighty Mouse, after Paul Terry decided to rename the Super Mouse character from The Mouse of Tomorrow, in which the mouse was originally conceived by Isadore Klein as a fly, before Terry stepped in and demanded he be made a mouse. Originally released in 1944, directed by Mannie Davis, story by John Foster (loosely inspired by Longfellow’s poem), with music by Philip A. Scheib. This is a 16mm sound version from Castle Films, which also released a silent 8mm version as well. The Wreck of the Hesperus later appeared on TV as part of Mighty Mouse Playhouse on CBS after Castle Films sold the entire Terrytoons library to CBS.