Sy Montgomery at work, interviewing an octopus. (Photo: David Scheel)

Sy Montgomery has written 20 nonfiction books, including some New York Times best sellers, but if you were unfamiliar with the focus of Montgomery’s work, within the first 90 seconds of my interview with her, you’d know.

“Animals have always given me the greatest joy of my life,” Montgomery explained, barely a moment after saying hello in our Jan. 13 Talking Animals conversation.

“And all this time—I’m 57—whenever I imagine heaven, it’s full of animals! And there are no people.”

She punctuates that last sentence with a hearty laugh, which seems important to mention because it might otherwise suggest she’s a critter-loving misanthrope.

Critter-loving? Absolutely. But Montgomery is far from misanthropic—she comes across as nothing but friendly, charming and pro-people in our radio chat.

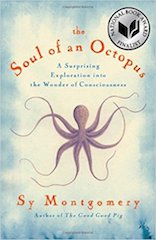

In her new book, The Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of Consciousness, Montgomery paints warm, affectionate portraits of her fellow adventurers at the New England Aquarium in Boston, who share her discoveries and growing enchantment with octopuses living there.

This cast of characters includes fellow volunteers, like Wilson Menashi, the retired inventor charged with the responsibility of creating tasks and puzzles to keep the octopuses challenged and engaged—providing “enrichment” for them—and Anna, a young girl who’s on the autistic spectrum, as well various Aquarium employees, notably including aquarist and main octopus man Bill Murphy.

Montgomery depicts wonderful humans throughout this nonfiction saga, from behind the scenes at the Aquarium, to the waters of Cozumel and Moorea. But the unquestioned star of this show is always the octopus.

Promoting The Soul of an Octopus, Sy Montgomery talks turkey about octopuses

Or, really, a number of octopuses. (We learn in the first page of her book, and early in the radio conversation, that’s correct for the plural–not “octopi.” Montgomery explained: “I am told by scientists who study them that ‘octopus’ is a Greek word and you can’t put a Latin ending—which is the plural ‘I’—on a Greek word.”)

Montgomery has written books about a slew of animals, including birds, dogs, pink dolphins, bears and, famously, a pig name Christopher Hogwood–her 2007 memoir about life with Hogwood, The Good Good Pig, became a New York Times bestseller.

Between the books, as well as the sweeping array of fauna-oriented newspaper and magazine articles she’s authored, it’s patently clear that she enjoys mixing it up, even clearer that she’s driven both by passion and curiosity.

Still, even seasoned Montgomery observers might’ve been hard-pressed to anticipate she’d write a book about octopuses.

But you don’t have to travel many pages into the book before you recognize that Montgomery is absolutely enchanted with octopuses, and along the way she is imparting octopus information that most of us probably did not know.

Part of the charm of The Soul of an Octopus, I think, is that she conveys those revelations with infectious enthusiasm—her sense of discovery becomes our sense of discovery.

Asked about the more surprising aspect of octopus life and behavior in the Talking Animals interview, Montgomery radiates that same gusto.

“First of all, you just have to go into outer space to find a creature more unlike a person than an octopus,” she said.

“Here’s somebody who can taste with all of their skin, including their eyelids. Here is somebody with no bones at all who can pour their body as if it were fluid down the drain. They can sink, like butter into an English muffin, into the tiniest holes.

“Yet, it’s a predator who hunts, and who when it catches its prey, can tear it apart with its very strong suction cups. A three-inch diameter suction cup on an octopus can lift 30 pounds, and they have 200 on each arm—at least, the Giant Pacific does.

In this TEDx talk Sy Montgomery presents the overwhelming evidence that animals across a wide variety of species do think and feel and experience consciousness

“So you can imagine the strength of the animal. They also have a beak like a parrot, and venom like a snake, and ink like an old-fashioned pen.

“And add to this, they can change color and shape at will. And they can multi-task in a way that we certainly can’t: even if an arm is severed, that severed arm can go off and do stuff. So they have superpowers that we can hardly dream of.

“And yet as different as they are, as amazing as they are, their minds are not so unlike ours that we can’t recognize each other as individuals. That octopuses can form relationships with people, they recognize individual people.

“It’s not just my feeling about that. It’s not just me projecting this on to an octopus—this has been demonstrated by scientists.

“They definitely can recognize a person, just looking up through the water at them. And they like some people, and they dislike others. And sometimes, that like or dislike, as with people, is based on stuff we can’t understand.

“Sometimes they like you because you gave them a nice fish, or you always pet them. But other times, there have been cases in which octopuses just didn’t like someone and would squirt that person every time they saw them.

“Even months later, when the octopus hadn’t seen that person in months and months, the person will come back, and the octopus will squirt them with cold water.”

At this point, I assume it’s unnecessary to include a spoiler alert before explaining that Montgomery is decidedly not a person that was disliked—or squirted—by any octopuses.

On the contrary, she hit it off with the octopuses she met at the New England Aquarium, and more than a little of the book describes and explores the way she forges a connection with some of these captive cephalopods. (The book also chronicles her adventures, and misadventures, in getting certified in scuba diving so that she could meet some octopuses in the wild. How those creatures felt about Montgomery is less clear, but I’m guessing they also liked her.)

At the Vancouver Aquarium discusses her fascinating relationship with the four-foot-tall octopus Athena

She provides accounts of spending extended periods with the octopuses, recounting such a profound bond that developed with some that they would reach an arm out of the water and essentially hold hands with Montgomery.

“Oh, yeah, and that’s an amazing feeling, let me tell you,” she recalled, with the breathy enthusiasm that marks so much of our conversation.

“I mean, when I would describe to friends the first time I touched an octopus–it was Athena, she was my first–and it was a wonderful experience. But I would watch their faces, and they would recoil in horror, because it sounded scary.

“Octopuses have been portrayed as monsters for so many years. And the idea of somebody’s slime-covered, cold suckers reaching up and grabbing on your skin, to suck on it and taste it, sounds a little alarming. But you realize here’s an animal who’s interested in you, who’s just as interested as you, as curious about you, as you are about them.

“And then later, an animal who’s just as eager to hug and kiss you as you are to stroke and pet them, that’s an amazing thing to have a bond with somebody like that. I felt as lucky, and as privileged, as the child protagonist in E.T. to have met somebody like that.”

Of course, that these octopuses took an immediate shine to Montgomery, or that she would speak in such rapturous terms about them is unsurprising to anyone who’s read her books, or otherwise followed her career. The Boston Globe once described her as “part Indiana Jones and part Emily Dickinson.”

If ever there was someone classically simpatico with animals, it’s Sy Montgomery. And this unusual kinship extends back to her formative years, when she was an army brat.

That sort of itinerant childhood can pose challenges to making—and especially, maintaining—friends. For Montgomery, a natural way to meet that challenge was initiating friendships with animals.

From the Port Townsend Marine Science Center, a short film of Athena the octopus at home

“Even on an army base, there’s a chance to observe crickets and bees,” she said. “There’s a chance to see birds and rabbits. Growing up, I had a sister, essentially, who was a Scottish terrier.

“We were both pups together. So I never looked at her as an underling of any kind. I was very aware that she attained adulthood before I did, and that she had senses that I did not…

“So lots of animals were important to me growing up. And they teach you, as a child, to be patient and to watch. Because if you’re wiggly and screaming and running around all the time, the animals will run away.”

Nearly fifty years after Montgomery was a kid, the lessons animals taught her about patience and watching served as the core of the material that animates The Soul of an Octopus.

She spent hours and hours and hours observing octopus friends—Athena, Octavia, Kali—much of that time engaging in a number of tactile experiences with them, yielding a wealth of anecdotal evidence alongside the traditional research and shoe leather reporting she conducted for the book.

It’s safe to say she emerged from this experience profoundly changed, with a newfound appreciation and expertise about these magical mollusks.

“What some people would consider heresy,” she said, “is now considered scientific truth: that fish, and marine invertebrates, have feelings, can learn, have the same emotions that we do.

“And we know now this is true, but many of us suffer from this ignorance and just refusing to listen to the facts.

“Many people say to me, ‘Oh, do fish feel pain?’ Of course they feel pain. They have a nervous system, just like ours. Our body plan is pretty much adapted from the fish plan.

“And octopuses feel pain, and you can tell, because they will guard something that is injured. Sometimes they’ll rub something that is an injured spot. And fish will do the same thing.

“But the folks at the Aquarium—they knew this. They knew that the octopuses want to play. They knew that you could train a fish to do tricks. They knew that individual fish—individual lobsters—have individual personalities.

“To some people, that’s threatening, but to me, it makes me feel so much more at home in this world, and makes the world so much more alive, believing that these creatures aren’t automatrons, just going through their lives mechanically.”

Far from it.

In fact, as the conversation was drawing to a close, I observe that by the end of her book, I couldn’t help thinking there is a tragic poignancy that characterizes the lives of octopuses.

Octavia the octopus, whom Sy Montgomery saw laying eggs at the New England Aquarium: ‘They’re such devoted mothers. And in the wild, they will never eat again, once they lay their eggs, because they will not leave those developing eggs. Not to hunt, or to eat. They will never leave them.’

For example, their very short life span (as little as six months; ones with great longevity live three to five years), and how female octopuses hasten the end of that short life by laying eggs–essentially, becoming a mother brings them to the end of the road.

“That’s right,” she responded instantly, “they’re such devoted mothers. And in the wild, they will never eat again, once they lay their eggs, because they will not leave those developing eggs. Not to hunt, or to eat. They will never leave them.

“What a compelling thing to see. And Octavia, the octopus who laid eggs while I was there, watching her care for them, assiduously cleaning them, guarding them. We handed her food on the end of a grabber, and often she would accept that food.

“But she didn’t come up to greet us. We were so low on her list of priorities once she had those eggs. And it was a really inspiring, moving thing to see. And it was great for the visitors to the New England Aquarium to see that, as well.

“Once they figured out what they were looking at, people were very deeply moved by this. And it totally changed their minds about who an octopus is.”

That makes total sense. Much the same could be said about The Soul of an Octopus.

Click here to visit the Jan. 13 Talking Animals installment with Sy Montgomery

About the Author: Combining his passions for animals, radio, journalism, music and comedy, Duncan Strauss launched Talking Animals at KUCI in California in 2003. Since late 2005 the show has aired on Tampa’s WMNF. Producer-host Strauss lives in Jupiter Farms, FL, with his family, including four cats, two horses and one dog. He spends each day talking to those animals, and maintains they talk right back to him, a claim as yet unverified by credible sources.