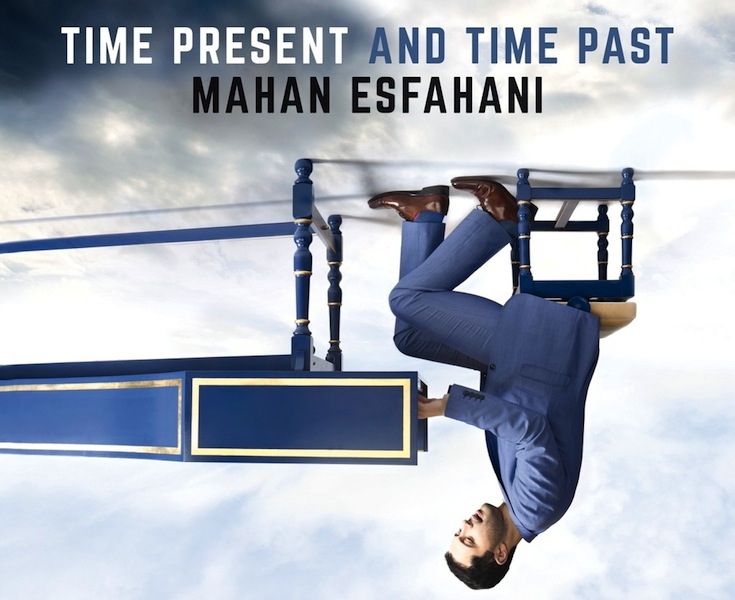

TIME PRESENT AND TIME PAST

Mahan Esfahani

ARCHIV Produktion (DG)

This new Mahan Esfahani disc on DG’s Archiv label re-invigorates the concept of a harpsichord recital by combining baroque music with contemporary. Three works based on La Follia, Alessandro Scarlatti’s Variations on La Folia, CPE Bach’s 12 Variations on Les Folies d’Espagne in D minor and Geminiani’s Concerto Grosso in D minor are threaded round Henryck Goreck’s Concerto for Harpsichord and String Orchestra from 1980 and Steve Reich’s 1967 classic, Piano Phase for Two Pianos in Mahan Esfahani’s version for two harpsichords. The final item is Bach’s Harpsichord Concerto in D minor, BWV 1052. For the Bach, Geminiani and Gorecki, Mahan Esfahani is joined by the period instrument ensemble Concerto Koln.

The disc opens with something of a coup. Alessandro Scarlatti’s dazzling keyboard pyrotechnics in the Variations on La Follia are followed by the full-on high-energy of Gorecki’s concerto. The Scarlatti is highly inventive and Esfahani’s performance is brilliantly vivid, combining stupendous technique with a strong sense of character.

Mahan Esfahani discusses the concept and music of Time Present and Time Past (album trailer)

Gorecki’s concerto is in two fast movements, both almost pitting the instrument against the orchestra. With a solo part taken at a rather mad speed, the opening Allegro Molto is full on but rather austere in its limited sound world. The harpsichord’s incessant toccata-like repetitions seem designed to try to push the slow moving, sustained orchestral part out of its harmonic rut. The final Vivace (no relaxing middle movement) is high energy, with the violence sometimes recalling Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps on speed. The performance from Esfahani and the orchestra is stupendous. I would be fascinated to hear the work played on modern instruments, and wondered what tonal effect the (presumed) gut strings had on the work. Regardless, the sound world is vivid and energized throughout.

After the harmonic tug of war of the Gorecki, CPE Bach’s variations return us to the world of harmonic inventiveness. But Mahan Esfahani finds analogies between the baroque use of cellular motifs in variation form and the minimalist works. He plays Bach’s variations with verve, bringing excitement and character to the piece. The warm toned harpsichord is a 2012 Bukhard Zander after a harpsichord by Joannes Daniel Dulcken (Antwerp, 1745). Mahan Esfahani uses this instrument for all the items on the disc except the Scarlatti, which is played on a 2010 Detmar Hungerberg “false inner-outer” after Florentine models of the 17th century.

An excerpt from Steve Reich’s Piano Phase for Two Pianos (1967) by Mahan Esfahani on harpsichord, from Esfahani’s album Time Present and Time Past

Francesco Geminiani’s Concerto grosso in D minor is based on Arcangelo Corelli’s Violin Sonata Op.5 No12, La Follia. Here Mahan Esfahani takes something of a back seat playing the continuo part (an important role, but not a solo one and thankfully, he does not try to make it so). Lasting over 11 minutes it is a multi-sectional work exploring different variations on La Follia with Geminiani seemingly interested in the multiplicity of different textures that could be achieved with his chosen group of performers. After a grand and stately opening, we have playing of great character and brilliance, with rhythmic vitality. There were times when I did worry that the string tone was a little too insistent with a hard edge creeping in, but overall the effect was bravura.

The sound world of Steve Reich’s Piano Phase for Two Pianos could not be more different: Two keyboards (recorded multi-tracked) as Reich explores the effects of the keyboards going in and out of unison. It was Reich’s first attempt at applying to live instruments a phasing technique he had used with tape. The players start in unison; one then gradually speeds up and thereafter the interest in the piece is what happens to the sound as the players play these speed games. The crisp attack of the harpsichord (strings plucked not hit) and quick die off of notes mean that the pitch shifts become mesmerizing, as is Mahan Esfahani’s performance. In this and in the Gorecki you do wonder whether the scores come with a warning about RSI.

An excerpt from J.S. Bach’s Concerto for Harpsichord No. 1 in D Major, by Mahan Esfahani, from his new album Time Present and Time Past

The final work on the disc is Johann Sebastian Bach’s harpsichord concerto, which was probably based on a highly virtuosic lost original violin concerto by Bach. The transfer to harpsichord concerto simply kept the string parts and made the busy violin part an even busier harpsichord part. The opening Allegro has robust strings with a strong bass sound, which contrast with the harpsichord part, which is more busy texture than harmony. The result is a big bold noise, and some bravura playing all round. The Adagio has darkly sinister strings in unison, contrasting with a meditative, singing harpsichord part. With the final movement we return to the busy bravura world of the opening with a lovely perky Allegro. Throughout the balance is superb; unlike some performances of these concertos no allowance has to be made for the solo instrument.

Intellectual gadfly Norman Lebrecht interviews Mahan Esfahani before the release of the latter’s debut album. Esfahani discusses his attraction to the harpsichord, the music he loves to play and where he’s hoping to take the instrument in the future.

One of the beauties of Mahan Esfahani approach is his combination of superb technique with questing intelligence. Throughout this disc you feel him prodding and pushing the genre (and prodding and pushing us, the audience) to see where it takes him. If you have ever wondered how the harpsichord could be brought into the contemporary era, then listen here.

Reprinted by permission of Robert Hugill, “singer, composer, journalist, lover of opera and all things Handel.” For more of Mr. Hugill’s classical reviews and interviews, visit Planet Hugill—A World of Classical Music.