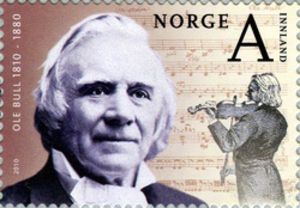

Ole Bornemann Bull (5 February 1810-17 August 1880): ‘He cannot be judged by the usual standards, his genius is exceptional, intensely individual in all its forms and methods, belongs to the very extreme of the romantic as distinguished from the classical in art.’

The following is an excerpt from Henry C. Lahee’s book Famous Violinists of To-Day and Yesterday, published by Boston The Page Company Publishers in 1899, with the ninth and tenth editions (in 1912 and 1916, respectively) published by L.C. Page and Company Inc. and the Colonial Press C.H. Simonds Co., of Boston. As stated in the book’s preface, the author’s intent was to provide “a bird’s-eye view of the most celebrated violinists from the earliest times to the present day rather than a detailed account of a very few. Necessarily, those who have been prominently before the public as performers are selected in preference to those who have been more celebrated as teachers. Lahee’s book, now in the public domain, is available for reading and download at Project Guttenberg.)

“A typical Norseman, erect of bearing, with a commanding presence and mobile, kindly face, from which the eyes shone clear and fearless as the spirits of old Norway hovering over his native mountains. He was a man to evoke respect and love under all conditions, and, when he stepped before an audience, roused an instantaneous throb of sympathy, of interest, before the sweep of his magical bow enthralled their souls with its melodious measures.” Such is an excellent pen picture of Ole Bull, who during the middle of the nineteenth century was known far and wide as a great violinist.

Among the celebrated musicians of all nations, Ole Bull will always remain a striking figure. As a musician, none so eminent has been so essentially a self-made man, none has grown up with so little influence from outside, none with a technique so essentially self-discovered. As a son of his country, none has retained so sturdy a sense of patriotism; none has, amid the more brilliant surroundings of a life spent in the gayest cities of the world, refused to be weaned from the poor northern, half-dependent state from which he issued a penniless lad.

Olaus Borneman Bull was born at Bergen, in Norway, February 5, 1810, and was the eldest of ten children. His father was a physician and apothecary. He was musical, as were several other members of his family, and little Ole’s love for music was fostered to a great degree at home by the Tuesday quartet meetings, at which his Uncle Jens played the ‘cello.

In the early part of the century, the proverb, “Spare the rod and spoil the child,” was regarded as the foundation of education in most countries, and few children were allowed to spoil. All childish desires which conflicted with parental ideas were promptly suppressed by “the rod,” until by sheer strength they proved to be unsuppressible. Then they became great virtues. It was thus with Ole Bull. His first desire to hear the quartet music, which he gratified by hiding under sofas or behind curtains, was rewarded with the rod,—for he should have been in bed. After a time a concession was made through the intervention of Uncle Jens, and Ole was allowed to become familiar with the best music of the day.

Uncle Jens used to amuse himself with the small boy’s susceptibility to music, and would sometimes shut him up in the ‘cello case, promising him some candy if he would stay there while he (Uncle Jens) played. But Ole could never endure the ordeal for long. He had to come out where he could see and hear.

His first violin was given him by Uncle Jens when he was five years old, and he soon learned to play it well without any instructor. He was not allowed to practise music until his study hours were over, and occasional breaches of this rule kept “the rod” active.

Ole Bull’s Violin Cloncerto in A Major (‘Grand Concerto’), Op. 4 (1834, revised 1864). The first violin concerto by the famous Norwegian composer and virtuoso violinist Ole Bornemann Bull (1810-1880). Annar Follesø, violin; Ole Kristian Ruud, conductor; Norwegian Radio Orchestra. I. Andante maestoso–Allegro maestoso (0:00); II. Adagio sentimentale: Adagio sostenuto (12:39); III. Rondo pastorale: Moderato (15:38).

Ole Bull’s first instructor was a violinist named Paulsen, a man of convivial temperament, who used to come and enjoy the hospitality of Ole’s father and play “as long as there was a drop in the decanter,” with a view to educating the young artist, as he said. But Ole’s parents were thinking of prohibiting the violin altogether on the plea that it interfered too much with his studies, when the tide of affairs was changed by the following incident.

One Tuesday evening, Paulsen, who played first violin in the quartet, had been so convivial that he was unable to continue. In this unfortunate dilemma Uncle Jens called upon Ole, saying, “Come, my boy, do your best, and you shall have a stick of candy.” Ole quickly accepted the challenge, and as the quartet was one which he had several times heard, he played each movement correctly, much to the astonishment of all present.

This happened on his eighth birthday, and the event marked an epoch in his life, for he was elected an active member of the Tuesday club, and began to take lessons regularly of the convivial Paulsen.

There is a pathetic story of how Ole induced his father to buy a new violin for him, and, unable to restrain his desire to play it, he got up in the night, opened the case, and touched the strings. This furtive touch merely served to whet his appetite, and he tried the bow. Then he began to play very softly; then, carried away with enthusiasm, he played louder and louder, until suddenly he felt the sharp sting of his father’s whip across his shoulders, and the little violin fell to the floor and was broken.

From 1819 to 1822 Ole Bull received no violin instruction, for Paulsen had left Bergen without explanation, though it has been hinted that Ole Bull had outgrown him, and on that account he thought it wise to depart.

In 1822 a Swedish violinist came to Bergen, and Ole took lessons of him. His name was Lundholm, and he was a pupil of Baillot. Lundholm was very strict and would admit of no departure from established rules. He quite failed to make the boy hold his instrument according to the accepted method, but his custom of making his pupil stand upright, with his head and back against the wall while playing, no doubt gave to him that repose and grace of bearing which was so noticeable in later years. Lundholm was, however, quite unable to control his precocious pupil and a coolness soon sprung up between them, which appears to have culminated in the following incident.

On a Tuesday evening, at one of the regular meetings, Lundholm played Baillot’s “Caprizzi,” but Ole Bull was much disappointed at the pedantic, phlegmatic manner in which he rendered the passionate phrases. When the company went to supper Ole found on the leader’s music-rack a concerto of Spohr’s, and began to try it over. Carried away with the music, he forgot himself, and was discovered by Lundholm on his return, and scolded for his presumption.

Ole Bull, ‘Sæterjentens Søndag’ (‘The Herdgirl’s Sunday’). Annar Follesø , violin; Ole Kristian Ruud , conductor; Norwegian Radio Orchestra.

“What impudence!” said the violinist. “Perhaps you think you could play this at sight, boy?” “Yes,” was the reply, “I think I could.” His remark was heard by the rest of the company, who were now returning, and they all insisted that he should try it. He played the allegro, and all applauded except Lundholm, who looked angry. “You think you can play anything,” he said, and, taking a caprice of Paganini’s from the stand, he added, “Try this.” It happened that this caprice was a favourite of the young violinist, who had learned it by heart. He therefore played it in fine style, and received the hearty applause of the little audience. Lundholm, however, instead of raving, was more polite and kind than he had ever been before, and told Ole that with practice he might hope to equal him (Lundholm) some day.

Years afterwards, when Ole Bull was making a concert tour through Norway, and was travelling in a sleigh over the snow-covered ground, he met another sleigh coming from the opposite direction, of which the occupant recognised him, and made signs to him to stop. It was Lundholm. “Well,” shouted he, “now that you are a famous violinist, remember that when heard you play Paganini I predicted that your career would be a remarkable one.”

“Oh,” exclaimed Ole Bull, “you were mistaken, for I did not read that piece, I knew it before.” “It makes no difference,” was the reply, as the sleighs parted.

As young Ole approached manhood, and developed in strength and stature, we find him asserting his independence. His father, who intended him to be a clergyman, engaged a private tutor named Musaeus, who, when he found that Ole’s musical tastes conflicted with his studies, forbade him to play the violin, so that the boy could only indulge at night in an inclination which, under restraint, became a passion. Ole and his brothers had long and patiently borne both with cross words and blows from this worthy pedagogue, and at length decided to rebel. Accordingly when one morning at half-past four the tutor appeared and dragged out the youngest from his warm bed, Ole sprang upon him and a violent struggle ensued. The household was aroused, and in a few moments the parents appeared on the spot in time to see Musaeus prostrate upon the floor and suing for peace. Contrary to his expectations, Ole found himself taken more into his father’s confidence, and as a result he became more desirous than ever of carrying out his father’s wishes.

In 1828 he went to the university in Christiania, where, in spite of the best intentions, he soon found himself musical director of the Philharmonic and Dramatic Societies, a position which gave him independence, and somewhat consoled him for his failure to pass his entrance examinations for the university. His father reluctantly forgave him, and he was now, in spite of everything, fairly launched upon a musical career.

Ole Bull’s violin (Gasparo, Italy 1562)

He was not long contented to remain in Christiania. His mind was in a state of restless agitation, and he determined to go to Cassel, and seek out Spohr, whose opinion he desired to secure. He accordingly left Christiania on May 18, 1829. His departure was so hurried that he left his violin behind, and it had to be forwarded to him by his friends. This suddenness was probably caused by the fact that he had taken part in the observance of Independence Day on May 17th, a celebration which had been interdicted by the government.

On reaching Cassel he went to Spohr, who accorded him a cold reception. “I have come more than five hundred miles to hear you,” said Ole Bull, wishing to be polite. “Very well,” was the reply, “you can now go to Nordhausen; I am to attend a musical festival there,” Bull therefore went to Nordhausen, where he heard a quartet by Maurer, of which Spohr played the first violin part. He was so overwhelmed with disappointment at the manner in which the quartet was played by the four masters that he came to the conclusion that he was deceived in his aspirations, and had no true calling for music.

Spohr was a most methodical man, and had no appreciation for wild genius. He saw only the many faults of the self-taught youth, and coldly advised him to give up his idea of a musical career, declining to accept him as a pupil. Some five years later, Bull having in the meantime refused to accept this advice, which did not coincide with his own inclinations, Spohr heard him play, and wrote thus of him: “His wonderful playing and sureness of his left hand are worthy of the highest admiration, but, unfortunately, like Paganini, he sacrifices what is artistic to something that is not quite suitable to the noble instrument. His tone, too, is bad, and since he prefers a bridge that is quite plain, he can use A and D strings only in the lower positions, and even then pianissimo. This renders his playing (when he does not let himself loose with some of his own pieces) monotonous in the extreme. We noticed this particularly in two Mozart quartets he played at my house. Otherwise he plays with a good deal of feeling, but without refined taste.”

After his discouraging interview with Spohr, Ole Bull returned to Norway, making, on the way, a short visit to Göttingen, where he became involved in a duel.

Feeling that his own capabilities were worth nothing, after what he had seen and heard in Germany, Ole Bull returned home in a despondent state of mind, but, on passing through a town where he had once led the theatre orchestra, he was recognized, welcomed, and compelled to direct a performance, and thus he once more fell under the influence of music, and began to apply himself vigorously to improvement.

In 1831 he went to Paris in order to hear Paganini, and if possible to find some opportunity to improve himself. He failed to enter the Conservatoire, but he succeeded in hearing Paganini, and this, according to his own account, was the turning-point of his life. Paganini’s playing made an immense impression on him, and he threw himself with the greatest ardour into his technical studies, in order that he might emulate the feats performed by the great Italian.

‘A man of overwhelming confidence and charisma’: A profile of Ole Bull, still considered by many to be Norway’s greatest musician. Posted at YouTube by Viking Oceans. Bull’s biographer Harald Herresthal and Norwegian violinist Tor Jaran Apold discuss Bull’s achievements, technique and cultural impact. (Remember when the Grateful Dead played the Pyramids? Ole Bull did it first, in the 19th Century.)

His stay in Paris was full of adventure. He was hampered by poverty, and frequently in the depths of despair. At one time he is said to have attempted suicide by drowning in the Seine. There is also a story told to the effect that the notorious detective, Vidocq, who lived in the same house with him, and knew something of his circumstances, prevailed upon him to risk five francs in a gambling saloon. Vidocq stood by and watched the game, and Ole Bull came away the winner of eight hundred francs, presumably because the detective was known, and the proprietors of the saloon considered discretion to be the better part of valour. It was a delicate method of making the young man a present in a time of difficulty, but one of which the moral effect could hardly fail to be injurious.

At one time, when he was ill and homeless, he entered a house in the Rue des Martyrs in which there were rooms to let. He was received and treated kindly, and was nursed through a long illness by the landlady and her granddaughter.

He tried to secure a place in the orchestra of the Opéra Comique, but his arrogance lost him the position, for when he was requested to play a piece at sight, it seemed to him so simple that he asked at which end he should begin. This offence caused him to be rejected without a hearing.

Fortune, however, began at last to smile upon him when he made the acquaintance of M. Lacour, a violin maker, who conceived the idea of engaging him to show off his violins. Ole Bull accordingly played on one of them at a soirée given by the Duke of Riario, Italian chargé d’affaires in Paris. He was almost overcome by the smell of assafoetida which emanated from the varnish, and which was caused by the heat. Nevertheless, he played finely, and as a result was invited to breakfast the next morning by the Duke of Montebello, Marshal Ney’s son. This brought him into contact with Chopin, and shortly afterwards he gave his first concert under the duke’s patronage, and with the assistance of Ernst, Chopin, and other celebrated artists.

He now made a concert tour through Switzerland to Italy, and on reaching Milan he played at La Scala, where he made an immense popular success, but drew from one of the journals a scathing criticism, which, however humiliating it may have been, struck him by its truth.

“M. Bull played compositions by Spohr, Mayseder, and Paganini without understanding the true character of the music, which he marred by adding something of his own. It is quite obvious that what he adds comes from genuine and original talent, from his own musical individuality; but he is not master of himself; he has no style; he is an untrained musician. If he be a diamond, he is certainly in the rough and unpolished.”

Ole Bull sought out the writer of this criticism, who gave him valuable advice, and for six months he devoted himself to ardent study under the guidance of able masters. In this way he learned to know himself, the nature and limitations of his own talent.

Ole Bull’s Gaspar di Salo violin had a headscroll in the shape of a woman’s head, supposedly carved by the sculptor Benvenuto Cellini.

We now arrive at the point in Ole Bull’s career at which he became celebrated, and this was due to accident. He was at Bologna, where De Bériot and Malibran were to appear at one of the Philharmonic concerts. By chance Malibran heard that De Bériot was to receive a smaller sum than that which had been agreed upon for her services, and in a moment of pique she sent word that she was unable to appear on account of indisposition. De Bériot also declared himself to be suffering from a sprained thumb.

It happened that Madame Colbran (Rossini’s first wife) had one day heard Ole Bull practising as she passed his window, and now she remembered the fact, and advised the Marquis Zampieri, who was the director of the concerts, to hunt up the young violinist. Accordingly, Ole Bull, who had gone to bed very early, was roused by a tap on the door, and invited to improvise on the spot for Zampieri. Bull was then hurried off, without even time to dress himself suitably for the occasion, and placed before a most distinguished audience, which contained the Duke of Tuscany and other celebrities, besides De Bériot, with his arm in a sling.

His playing charmed and captivated the audience, although he was almost overcome with exhaustion. After taking some food and wine he appeared again, and this time he asked for a theme on which to improvise. He was given three, and, instead of making a selection, he took all three and interwove them in so brilliant a manner that he carried the audience by storm. He was at once engaged for the next concert, and made such success that he was accompanied to his hotel by a torchlight procession, and his carriage drawn home by the excited people.

Ole Bull continued his triumphant course through Italy. At Lucca he played at the duke’s residence, where the queen-dowager met with a surprise, as Ole refused to begin playing until she stopped talking. At Naples he experienced the misfortune of having his violin stolen, and he was obliged to buy a Nicholas Amati, for which he paid a very high price. After playing and making a great success in Rome, he returned to Paris, where he now found the doors of the Grand Opéra open to him, and he gave several concerts there.

In 1836 he married Félicie Villernot, the granddaughter of the lady in whose house he had met with so much kindness during his first stay in Paris.

Following the advice of Rossini, he went to London, where he made his usual success, notwithstanding the intrigues of certain musicians, who endeavoured to discredit him. Such was his popularity in England that he received for one concert, at Liverpool, the sum of £800, and in sixteen months’ time he gave two hundred and seventy-four concerts in the United Kingdom.

Adagio Religioso: En Moders Bøn (‘A Mother’s Prayer’). Arve Tellefsen, violin; Elvind Aadland, conductor, Trondheim Symphony Orchestra (a 2005 recording)

He now decided to visit Germany, and on his way through Paris he made the acquaintance of Paganini, who greeted him with the utmost cordiality. He went through Germany giving many concerts, and visited Cassel, where he was now received by Spohr with every mark of distinction. He played in Berlin, where his success was great, notwithstanding some adverse criticism. He also played in Vienna and Buda-Pesth, and so on through Russia. At St. Petersburg he gave several concerts before audiences of five thousand people. He now went through Finland and so on to Sweden and Norway, where he was fêted.

Although closely followed by Vieuxtemps and Artot, Ole Bull was the first celebrated violinist to visit America, and in 1843 he made his first trip, landing in Boston in November of that year and proceeding directly to New York, playing for the first time on Evacuation Day. “John Bull went out on this day,” he said, “and Ole Bull comes in.” He remained two years in the United States, during which time he played in two hundred concerts and met with many remarkable adventures. During his sojourn he wrote a piece called “Niagara,” which he played for the first time in New York, and which became very popular. He also wrote “The Solitude of the Prairies,” which won more immediate success.

He travelled during these two years more than one hundred thousand miles, and played in every city of importance. He is estimated to have netted by his trip over $80,000, besides which he contributed more than $20,000, by concerts, to charitable institutions. No artist ever visited the United States and received so many honours.

In 1852 he returned to America, and this time he was destined to meet with tribulation. It was his desire to aid the poor of his country by founding a colony. He therefore bought a tract of land of 125,000 acres in Potter County, Pennsylvania, on the inauguration of which he stated his purpose: “We are to found a New Norway, consecrated to liberty, baptised with independence, and protected by the Union’s mighty flag.” Some three hundred houses were built, with a store and a church, and a castle on a mountain, which was designed for his permanent home. Hundreds flocked to the new colony, and the scheme took nearly the whole of his fortune.

Ole Bull now started on a concert tour together with little Adelina Patti, her sister Amalia Patti Strakosch, and Mr. Maurice Strakosch. Patti was then only eight years old, and was already exciting the wonder of all who heard her.

When crossing the Isthmus of Panama his violin was stolen by a native porter, and Ole Bull was obliged to remain behind to find his instrument, while the company went on to California. He was now taken down with yellow fever, and owing to a riot in the town he was entirely neglected, and was obliged to creep off his bed on to the floor in order to escape the bullets which were flying about. On his recovery he set out for San Francisco, but the season was too late for successful concerts. He was miserably weak, and when he played his skin would break and bleed as he pressed the strings.

He now heard that there was some trouble in regard to his title to the land in Pennsylvania, and, hastening to Philadelphia, he was legally notified that he was trespassing.

It transpired that the man who had sold the land to Ole Bull had no claim to it whatever, and had perpetrated a barefaced swindle, and now, having the money, he dared his victim to do his worst. The actual owner of the land, who had come forward to assert his rights, became interested in the scheme, and was willing to sell the land at a low price, but Ole now had no money. He instituted legal proceedings against the swindler, who, in return, harassed the violinist as much as possible, trying to prevent his concerts by arrests, and bringing suits against him for services supposed to have been rendered. It is even stated that an attempt was made to poison him, which only failed because the state of excitement in which he was at the time prevented his desire for food.

Ole Bull, La Mélancolie (‘I ensomme stunde’ or ‘In Moments of Solitude’). Arve Tellefsen, violin; String Ensemble

Ole Bull now set to work to retrieve his fortunes, but ill luck still followed him, and he fell a victim to chills and fever, was abandoned by his manager, and taken to a farm-house on a prairie in Illinois, where he endured a long illness. For five years he continued his struggle against misfortune, and during that period he made hosts of friends who did much to help him in one way and another. Nevertheless, when he gave his last concerts in New York, in 1857, he was still so ill that he had to be helped on and off the stage.

He now returned to Bergen, where the air of his native land soon restored him to health. On his arrival, however, he found that the report had been circulated that he had been speculating at the expense of his countrymen, and that they were the only sufferers by his misfortunes.

For a short time he assumed control of the National Theatre, but before long he was again on the road, giving concerts in various parts of Europe. While he was in Paris, in 1862, his wife died.

The year 1867 found him again in the United States, and during this tour he met at Madison, Wis., Miss Sara C. Thorpe, the lady who was to become his second wife. He also took part in the Peace Jubilee in Boston, in 1869.

The violin of Ole Bull is quite special. NRK Hordaland made a film around the Norwegian violinist and composer Ole Bull (originally from Bergen, 1810-1880). Amnon Weinstein, winner of the Ole Bull prize 2007, was interviewed in his workshop to explain why there is a special sound in the violin. This extract is taken from the documentary ‘The Sound of Ole Bull’ with the permission of NRK Hordaland. More about the project Violins of Hope: www.shlomomintzviolin.com. With English subtitles.

When he sailed for Norway, in April, 1870 (he was to be married on his arrival), the New York Philharmonic Society presented him with a beautiful silken flag. This flag—the Norwegian colours with the star-spangled banner inserted in the upper staff section—was always carried in the seventeenth of May processions in Bergen, and floated on the fourth of July.

The remaining years of Ole Bull’s life were spent in comparative freedom from strife and struggle. He spent much of his time in Norway, but also found time for many concert tours. His sixty-sixth birthday was spent in Egypt, and he solemnized the occasion by ascending the Pyramid of Cheops and playing, on its pinnacle, his “Saeter-besög.” This performance took place at the suggestion of the King of Sweden, to whom the account was duly telegraphed the next morning from Cairo.

In Boston Ole Bull was always a great favourite and had many friends. He felt much interest in the Norsemen’s discovery of America, and took steps to bring the subject before the people of Boston. The result of his efforts is to be seen in the statue of Lief Ericsson, commemorative of the event, which adorns the Public Gardens.

In March and April, 1880, Ole Bull appeared at a few concerts in the Eastern cities, with Miss Thursby, and in June he sailed, for the last time, from America. He was in poor health, but, contrary to all hopes, the sea voyage did not improve his condition, and much anxiety was felt until his home was reached. A few weeks later he died, and, at the funeral, honours more than royal were shown. In the city of Bergen all business was suspended, and the whole population of the city stood waiting to pay their last respects to the celebrated musician and patriot.

Ole Bull was a man of remarkable character and an artist of undoubted genius. All who heard him, or came in contact with him, agree that he was far from being an ordinary man. Tall, of athletic build, with large blue eyes and rich flaxen hair, he was the very type of the Norseman, and there was something in his personal appearance and conversation which acted with almost magnetic power on those who approached him. He was a prince of story-tellers, and his fascination in this respect was irresistible to young and old alike, and its effect not unlike his violin playing.

Ole Bull, Sigrids sang (‘Sigrid’s Song’). Arve Tellefsen, violin.

In regard to his playing, his technical proficiency was such as very few violinists have ever attained to. His double stopping was perfect, his staccato, both upward and downward, of the utmost brilliancy, and though he cannot be considered a serious musician in the highest sense of the word, he played with warm and poetical, if somewhat sentimental, feeling. He has often been described as the “flaxen-haired Paganini,” and his style was to a great extent influenced by Paganini, but only so far as technicalities are concerned. In every other respect there was a wide difference, for while Paganini’s manner was such as to induce his hearers to believe that they were under the spell of a demon, Ole Bull took his hearers to the dreamy moonlit regions of the North. It is this power of conveying a highly poetic charm that enabled him to fascinate his audiences, and it is a power far beyond any mere trickster or charlatan. He was frequently condemned by the critics for playing popular airs, which indeed formed his greatest attraction for the masses of the people. He seldom played the most serious music, in fact, he confined himself almost entirely to his own compositions, most of which were of a nature to meet the demand of his American audiences.

When Ole Bull played in Boston in 1852, after having been absent for several years, during which time other violinists had been heard, John S. Dwight wrote of his performance thus: “We are wearied and confused by any music, however strongly tinged with any national or individual spirit, however expressive in detail, skillful in execution, and original or bold, or intense in feeling, if it does not at the same time impress us by its unity as a whole, by its development from first to last of one or more pregnant themes. As compositions, therefore, we do not feel reconciled to what Ole Bull seems fond of playing…. He cannot be judged by the usual standards, his genius is exceptional, intensely individual in all its forms and methods, belongs to the very extreme of the romantic as distinguished from the classical in art. He makes use of the violin and of the orchestra, in short of music, simply and mainly to impress his own personal moods, his own personal experience, upon the audiences. You go to hear Ole Bull, rather than to hear and feel his music. It is eminently a personal matter…. Considered simply as an executive power, he seems, after hearing so many good violinists for years past, to exceed them all—always excepting Henri Vieuxtemps.”

It may be said with truth that Ole Bull achieved his reputation at a time when it was comparatively easy to do so. There was very little musical cultivation in this country when he first appeared here, as may be easily imagined by a glance at the extracts from criticisms, given here and there. By his strong personality, apparent mastery of his instrument, and by being practically the sole occupant of the field, he became famous and popular. He prided himself on the fact that his playing was addressed rather to the hearts than to the sensitive ears of his audiences, and during his later years he adopted certain mannerisms by way of distracting attention from his somewhat imperfect performances. He never made any pretension to being a musician of the modern school, nor of any regularly recognized school of music, but his concert pieces were his own compositions, of no great merit, and he still more delighted his audiences by playing national airs as no one had ever played them before. He was a minstrel rather than a musician in the broad sense of the word, but he held the hearts of the people as few, if any, minstrels had previously done.