Allen Klein with Yoko Ono and John Lennon: for Lennon and Klein, respect and love outstripped conflict

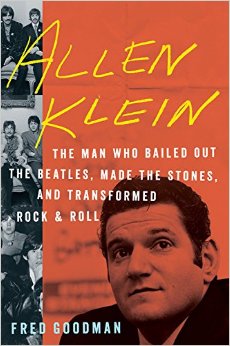

To my regret, I never got to know Allen Klein. Nevertheless, I enjoyed an up-and-down relationship with–as Fred Goodman describes him in his fascinating new book, Allen Klein: The Man Who Bailed Out The Beatles, Made The Rolling Stones, and Transformed Rock and Roll.

My ups-and-downs with Allen consisted of the occasional elevator ride at 1700 Broadway in Manhattan, where the offices of ABKCO, his company, occupied the 41st floor and my Record World Magazine colleagues and I toiled on 42. My sense of awe (mixed with a bit of fear) and Allen’s intense “Do not disturb” vibe limited our encounters to some variation of, “How’s it goin’?”–“Great!”

From time to time, our staffers reported elevated thrills with Klein clients like George Harrison (whom Klein helped mount the monumental Concert for Bangladesh), John Lennon (whose 1974 track “Steel and Glass” refers to 1700), and Phil Spector, who thanked our receptionist for pressing the 41 button without his having to ask. A peak non-Kleinian moment came when an aide to James Brown was spotted giving a haircut to the hardest-working man in show business en route to his throne on 39. More than once, we looked up (literally) to our neighbor on 42, ABA commissioner/former New York Knicks star Dave Debusschere, who joined us in being able to say that one band’s ceiling was another fan’s floor.

Sam Cooke, A Change Is Gonna Come, 1963

At a time when our publication was barely profitable, Klein was one of our most generous and lavish advertisers. ABKCO ran beautiful four-color pages or spreads with greater regularity than most major labels. Those ads didn’t sell records–we were a trade rag–but they signaled extra-mile support for his artists and let potential clients know that Klein would go to the wall for them if they would only let him. I think he was also reminding his adversaries that he played to win, and that if they tried to fuck with him he’d sue their asses forever or until they went away empty-handed, whichever came first.

Despite his potential leverage with Record World, Klein never asked for favors or complained about chart positions or editorial coverage. The only thing he insisted on–and this was sacred–was primo ad placement.

Goodman, author of several other books including the essential The Mansion on the Hill, did his own industry wood-shedding during the ’80s at Cash Box, a rival trade weekly HQed a few blocks north at 1775 Broadway. He explains in expert detail how Klein–beginning with Sam Cooke in the early ’60s, continuing with The Rolling Stones and other major acts and then the ultimate prize, The Beatles–deployed financial wizardry, a gift for negotiating, and fierce intimidation to strike visionary long-term deals for his clients.

Though Goodman clearly admires Klein, he doesn’t soft-pedal the man’s dark side, which was far more apparent in his empire-building years than later on. Klein, whose mother died when he was nine months old, spent part of his youth in an orphanage and was capable of brutality toward his enemies and belittling harshness to those he loved.

Occasionally, Klein’s negotiating savvy gave way to arrogance. One time, he blew off an IRS agent, an act of truculence that may have contributed to his loss to Paul McCartney in a British court battle. Years later, in a separate case, Klein was convicted of tax fraud and served a two month prison term for failing to report income from sales of promotional records.

The relationship between Klein and John Lennon–two geniuses with big egos and deep insecurities–was characterized by ups and downs that were more like roller coaster spills than elevator rides. In “Steel and Glass,” Lennon addresses Klein directly when he sings, “Your mother left you when you were small/But you’re gonna wish you wasn’t born at all,” (The song evokes John’s anti-Paul screed, “How Do You Sleep?” for which Klein supplied the perfect line, “The only thing you done was yesterday.”)

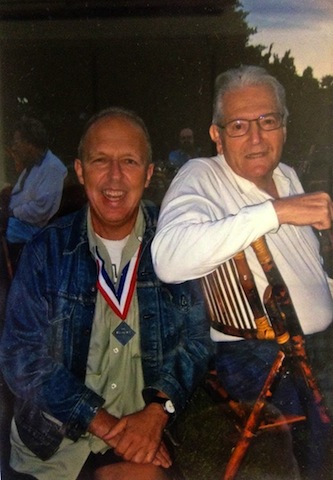

Long-time-ABKCO publicist Bob Merlis (left) with Allen Klein at an ABKCO summer bash. Pressed for comment, Merlis said (cryptically), “I was on the medal winning team.”

Goodman concludes, “In a lifetime of searching for love and validation, the closest Allen Klein had ever come to a soulmate was John Lennon.”

Klein made a fortune for himself as well as for his clients, of course. But you can’t read Goodman’s book without seeing that his subject cared deeply about those he repped–and about their music. In 1984, RCA Records A&R VP Gregg Geller, acting on a tip from former colleague and friend Joe McEwen, discovered an astonishing live Sam Cooke album languishing in the vaults.

Geller had concerns about whether Klein, who owned the rights to Cooke’s catalogue, would cooperate in releasing the material. In the event, Geller recalled, “Allen’s attention to detail was phenomenal…I saw that there is a reason artists gravitate toward him: he loves to do battle. And if he’s doing battle for you, you’re in great hands.” Cooke’s album, Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963, sparked a Sam Cooke revival and is widely acknowledged as one of the best live records of all time.

Gregg, a Record World alum, tells me, “Whatever trepidations I had were based almost entirely on the RCA business affairs department’s fear of AK, based on 20-plus years worth of contentious back and forth with him (in which he always got the best of them–and rightfully so. They were always in the wrong.)”

Respected industry vet/erstwhile Record Worlder Bob Merlis chimes in with this Allen anecdote: “ABKCO was one of my very first PR clients after Warner Bros showed me the door. AK thought I was the right guy to work on a new Sam Cooke package entitled ‘Keep Movin’ On.’ I was thrilled to have something to do with the legacy of Sam and have professional juxtaposition to Allen who had always been friendly with me at the annual party he threw at the Waldorf Towers folding each year’s RRHOF inductions. He kept me on and had me work on various projects including a massive Rolling Stones reissue program, etc.

“After a year or two I got a call from ABKCO’s GM, Iris Keitel, who said that Allen was in the office with her and he wanted me to know something. In lieu of putting him on the phone she related what he told her to tell me as he was saying it–I could hear his voice faintly in the background. ‘Allen says that because of the shitty job you’ve done and because you never call him…’ At this point I held my breath but I knew it was some kind of ploy because Iris said these things with a mirthful tone. ‘He wants to give you a raise…retroactively!’ I responded to Iris, ‘Please tell Mr. Klein that I shall endeavor to keep doing a shitty job and will do my best not to try to call him.’ It was Allen’s way of being both generous and foreboding but I really didn’t fall for it. I knew that deep inside he was very kind and I’ll never forget what he did for me. He was the only client I’ve ever had who gave me an unsolicited raise…for doing a ‘shitty job.'”

The Rolling Stones, ‘Satisfaction’

Klein died in 2009 of complications from Alzheimer’s, but his financial farsightedness and patience–paradoxical in a man whose thoughts sped so fast they made an ADD sufferer seem like a Zen Master–laid the groundwork for ABKCO Music & Records, with Allen’s son Jody at the helm, to thrive for decades to come. (Klein’s daughter Robin runs the film division.)

Today, the company owns the rights to compositions and recordings by Sam Cooke, The Rolling Stones, Bobby Womack, Eric Burdon, The Animals, Herman’s Hermits, Marianne Faithfull, and The Kinks as well as the treasure trove of material in the Cameo Parkway catalogue by such artists as Chubby Checker, Bobby Rydell, ? & the Mysterians, and Dee Dee Sharp.

Last summer, ABKCO released The Complete SAR Records Recordings, which L.C. Cooke–Sam’s younger brother–recorded before his brother’s death in 1964. (A Sam Cooke biopic is in pre-production.) Recently, the company put out SAR compilations on The Valentinos (Bobby Womack and his brothers) and The Soul Stirrers. And on July 10, ABKCO will release a limited-edition 12-inch of The Rolling Stones’ immortal single, “Satisfaction,” to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the original record reaching No. 1.

The Valentinos, ‘Lookin’ for a Love,’ from the ABCKO vaults

Allen Klein hits the streets just days before the debut of Apple’s new “music ecosystem,” which, Taylor Swift notwithstanding, feels to struggling musicians and songwriters like another nail in their coffers.

By force of will and with a singular imagination, Allen Klein made spectacular deals for his artists. Has the digital revolution made it impossible for music creators to reap fair compensation for their work? Or is there a budding deal-maker out there–someone who cares about music more than tech–with the talent and drive to take on Apple, Spotify, and Google the way Klein took on RCA, EMI, and CBS? If so, that revolutionary-in-the-making could start with the question, “WWAD?”–What would Allen do?

(Allen Klein: The Man Who Bailed Out The Beatles, made The Rolling Stones, and Transformed Rock and Roll is published by Eamon Dolan Books/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle, Audible, and Audio CD versions are available.)

Michael Sigman is a writer, editor, publisher and media consultant and the president of Major Songs, a music publishing company that handles the catalogs of his late father Carl Sigman and several contemporary songwriters. Sigman’s writing has appeared in Record World, LA Weekly, the L.A. Times, OC Weekly, The District Weekly, LA Style, The Bluegrass Special.com, Record Collector News, LA Progressive, Deep Roots and other newspapers and magazines. He is also the author of a biography of his father. He currently writes a weekly blog for Huffingtonpost.com.