Note: B.B. King, one of the titans of 20th Century American music, died in his sleep at his Las Vegas home on Thursday night, May 14. Rather than a standard obituary, Deep Roots is honoring this great artist with an excerpt from the book, B.B. King: There Is Always One More Time. Published by Backbeat Books in 2005 as part of the publisher’s Live in Music series, and written by Deep Roots founder/publisher/editor David McGee, There is Always One More Time, although largely biographical, is focused on the music B.B. made in the studio over the years and is the only book going into depth with producers and artists B.B. worked with about the making of many of his most important albums. The chapter reprinted here recounts an especially monumental summit meeting in which B.B. and producer Stewart Levine—who was searching for a fresh direction for B. after producing two acclaimed albums pairing him with the Crusaders—team up with towering songwriter Doc Pomus and the brilliant multi-instrumentalist Mac Rebennack, aka Dr. John, on a project that became near and dear to all these mens’ hearts, There Must Be a Better World Somewhere, released in 1981, a Grammy winner in 1982 as Best Ethnic or Traditional Recording. The project changed the course of Doc’s career and of Stewart Levine’s life, no less, as he recounts here in colorful detail to say the least.

What’s Up, Doc?

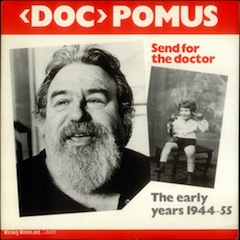

Doc Pomus: ‘I always figured I am the quintessential person—in other words, what I feel is what a lot of other people out there feel. I always write that way.’ (Photo: Sharyn Felder)

In New York City, Doc Pomus was emerging from a decade’s hiatus as a songwriter, a time when he too decided “it was time to rethink it.” He had gone into self-imposed retirement in 1965 “because I didn’t like what was happening.”1 Up to that point, though, he and his partner Mort Shuman had established themselves in the top tier of rock ’n’ roll songwriters, on a par with Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. They had amassed a stunning catalog of hits written for the Coasters, the Drifters (“Save the Last Dance for Me” among several elegantly crafted and breathtakingly produced—by Leiber and Stoller–love songs bearing the Pomus–Shuman copyright), Dion and the Belmonts (“Teenager in Love”), Ray Charles (“Lonely Avenue”), Bobby Darin, Andy Williams, and more than two dozen songs for Elvis Presley, including “Viva Las Vegas,” “Little Sister,” “(Marie’s the Name) His Latest Flame,” “Mess of the Blues,” and “Suspicion.” Pomus was a true urban romantic, his lyrics being both streetwise and tender hearted, mirroring the man himself.

An early Pomus-Shuman classic, ‘Hushabye,’ The Mystics, 1959

A big man with a big heart, born June 27, 1925, Pomus, né Jerome Felder, was a Brooklyn native (as a toddler he was voted Brooklyn’s Most Beautiful Baby) and an early convert to the blues as sung by Big Joe Turner, his favorite number being “Piney Brown Blues.” While still in his teens he began playing local clubs (afflicted with polio at age six, he walked and performed on crutches), modeling his rugged singing style after Big Joe’s. In his late teens he hung out at George’s Tavern in Greenwich Village, where Frankie Newton’s band held forth. Eventually he wrangled a singing gig at the club, simply in order to stay in the place.

“What was really interesting was the fact that I didn’t know any blues,” Pomus said. “I just knew one or two, and I started singing in the place because I saw the owner was about to throw me out for hanging around the bandstand. So I told him I was a singer, and Frankie Newton, a great trumpet player and a really nice fellow, told me to sit in with the band. I knew one blues at that time, ‘Piney Brown Blues,’ and I did ‘Piney Brown,’ and when they asked me to do an encore, I did ‘Piney Brown’ again. I really was not so much a blues fan then, but a Joe Turner fan. I didn’t start collecting records of my favorite singers till I was in my twenties.”

Pomus built up a repertoire and a reputation as a solid blues shouter and talented writer, and by 1945, at age 19, he was making his first recordings as a solo artist, for the Apollo label. He assembled a number of bands over the years, invariably drawing premier players into his fold, including, at one time in the same group, saxophonist King Curtis and guitarist Mickey Baker. He recorded for several different labels over the next ten years, but his only hit came in 1955, when his song “Heartlessly,” for the Dawn label, was championed by pioneering rock ’n’ roll disc jockey Alan Freed and became a local hit. RCA bought the master recording, intending, Pomus believed, to break it nationally. Instead, for reasons that were never explained to him, the label killed the single and with that, Pomus’s career as a solo artist.

“We never knew what happened,” Pomus said of the demise of “Heartlessly.” “As soon as the record started opening up in New York, it got killed. But Alan Freed had stayed on the record for several weeks straight and was real excited about it, swore it was a hit. In those days Alan was never wrong. It depressed me so much that eventually I stopped singing, because I thought that was my big chance.

“I had been so poor all my life and now it just didn’t seem to be going anywhere. It looked like ultimate disaster to me, so I packed it in.

Doc Pomus’s 1950 recording of his song ‘Send For the Doctor’

“I was barely surviving with that. Then I said I would be a songwriter exclusively. Then I started thinking that the best thing to do is to write a lot of songs; you can’t survive writing a few songs as a songwriter. So I found this kid who had been hanging out with my cousin at parties and I broke him in. I let him stay in the room when I wrote a song and every time he was there I would give him like 10 percent of the song, or 15 percent. This went on for years. Finally one day years later I said, ‘You’re my partner,’ and from then on he got 50 percent of the songs. But he went through like an apprenticeship with me for years. Just for being in the room I’d give him 10 percent, 15 percent, 20 percent. That was Mort Shuman, and eventually we became full-time partners and eventually we were very successful.”

Very successful, indeed, right up to the moment in 1965 when, discouraged by the direction popular music was taking, he broke up the partnership. What never left him, though, was his love of the blues and of blues artists, not only Big Joe Turner, who had become his close friend, but T-Bone Walker, Johnny Adams, B.B. King, Ray Charles—their records dominated his extensive collection. Despite all the hits bearing the Pomus–Shuman credit—none of which he disavowed—the music that continued to speak to him on intimate terms about his life was the blues.

In the mid-’70s he had become acquainted with Mac Rebennack, the gifted and charismatic New Orleans guitarist-keyboardist known professionally as Dr. John, an alter ego Rebennack assumed in 1967. Dr. John, in fact, was a real New Orleans character, a root doctor who, according to Rebennack, “was preeminent in the city for the awe in which he was held by the poor, and the fear and notoriety he inspired among the rich”; later in life Rebennack learned that the real Dr. John and a lady named Pauline Rebennack, whose relationship to Mac Rebennack remains uncertain, were arrested for running a voodoo operation and a whorehouse. The modern-day Dr. John, originally christened as Dr. John the Night Tripper, turned his concerts into spiritual, mystical, hallucinatory, and rhythm-bound N’awlins celebrations, with the master of ceremonies decked out in resplendent, colorful plumes, symbolic face paint, beads, and walking sticks (one sported a shrunken head), all the while advancing some seriously deep grooving music born of those infectious Crescent City second-line rhythms. If Dr. John’s entire presentation seemed informed by drugs and drug culture, well, that part wasn’t necessarily a show: Rebennack had been using narcotics since his early teens and was introduced to heroin, his drug of choice, around his fifteenth year. It could be said with some degree of accuracy that his highs informed his art. Image aside, though, he was a supremely gifted musician, dedicated to his craft and serious in his musical explorations. He was still in junior high school when he sold some of his original songs to the Specialty label, for Little Richard, who periodically came through town to record, and to Art Neville, then working in a local band; also as a teenager, he began sitting in on guitar on sessions with some of the great names in New Orleans R&B. In 1965 he moved to Los Angeles, and became an in-demand session player (working with Phil Spector, among others) before he started his solo career in earnest. Although never a major pop artist, he did have a Top Ten hit in 1973 with the slinky “Right Place Wrong Time,” one of the last mainstream chart incursions of New Orleans–influenced pop.

Pomus and Rebennack hit it off both personally and professionally. Producer Joel Dorn, whose impressive résumé ranges from Bette Midler to Roberta Flack (“Killing Me Softly” was a Joel Dorn production), from Roland Kirk to the Neville Brothers, put the two together to write a song, “a new national anthem,” according to Dr. John, for a movie Dorn was backing. The movie project failed to materialize, but the two doctors forged a deep bond and lasting memories from their aborted first collaboration. “I’ve still got a fond spot in my heart about that project,” Dr. John said, “because Joel used to talk about having Fathead Newman, one of my closest partners, dribbling a basketball with one hand and playing his sax with the other during this national anthem.”7 The friendship blossomed commercially in 1978 and 1979 when they teamed to write most of the songs on Dr. John’s Tango Palace and City Lights albums (both of them co-produced by Rebennack’s buddy and B.B. session veteran Hugh McCracken). In that same time frame Pomus had ventured tentatively back into the rock world by writing three songs for Willie DeVille’s Le Chat Bleu, which was released in 1980 and wound up winning an Album of the Year citation from Rolling Stone magazine.

Dr. John performs the Doc Pomus-Mac Rebennack title track from the Dr.’s 1978 album City Lights

All of these more recent songs demonstrated the growth in Pomus’s writing. The urban settings were still there, but the emotions were more complex; no more teen dramas or fears of the other guy stealing his girl, but rather an internal monolog about survival, within a relationship, within the context of getting through a day, and serious thought as to the meaning of love, the quest for love, the necessity for love—themes that illuminated Pomus’s life, in fact and in song.

One night in the mid-’80s, while suffering with a toothache, he was trying to find something on late-night TV to distract him from his pain. Lo and behold, there was Charlie Rose hosting the talk show “Nightwatch” on CBS. His guest was B.B. King. What Pomus saw inspired him to reflect on his raison d’être as a songwriter in his later years, and those ideas were already in place at the moment producer Stewart Levine was rethinking the approach to B.B.’s next album.

“As usual the interview was very interesting because B is so articulate and always finds new things to say and he’s so gracious,” Pomus said. “After the interview ended, out of the clear blue, Charlie asked him, ‘What’s your favorite song?’ So he said, ‘I have two favorite songs. One of them is a song Willie Nelson recorded called ‘Always on My Mind,’ and the other is a song Johnny Adams recorded called ‘A World I Never Made.’”

Pomus was shocked, because the Johnny Adams song was one he had written, and he had no idea B.B. had ever heard it, much less liked it.

Johnny Adams, ‘A World I Never Made,’ written by Doc Pomus and identified by B.B. King as one of his favorite songs, much to Doc’s surprise

“The thing that really moved me about it was that this is one of the songs I’ve written in the last few years, and these represent to me a different approach to writing. This is one of those songs that I’ve written that I write to an older audience. When I was writing 20, 25, 30 years ago a large part of the thrust of my writing was geared towards young people. But today the thrust of my writing is to older people, and I think I went back to my roots. Originally when I started writing songs—and at that time I was writing by myself—I was writing to an adult audience, blues or rhythm and blues. The audience at that time was adults mostly, and some young people bought records incidentally. So here I’m going back again to those kinds of roots, to people who are out there stumbling in the night, but they’re all adults doing that. I think basically they’re kind of lost, have a lot of problems—problems with women, problems with finances, problems with just trying to figure out who they are, and mostly trying to get through the night. You’re out there at night and there’s a world surrounding you, and it looks cold and it looks distant. You don’t feel like you’re really a part of it. At least I always figured I am the quintessential person—in other words, what I feel is what a lot of other people out there feel. I always write that way.

“I think young people have some of those same feelings, but they haven’t lived the years in this world to experience a lot of those things to the depth, and the feelings aren’t as extended as they with older people. After all, I’m 63 years old; I’m operating with a wide, wide range of experience.”

Doc Pomus and Mac Rebennack: Their demos for There Must Be a Better World Somewhere were, says producer Stewart Levine, “outrageous. They were beautiful. I thought these songs were masterpieces.’

B.B. needing a new direction, and his contemporary Doc Pomus focused on writing songs that addressed issues and feelings common to older adults, seemed to Levine to be a good place to start a new album. Over the phone the producer described for Pomus what he was looking for, and about a month later, in the fall of 1980, a cassette arrived in his mailbox. When he played it, he was “absolutely stunned” by what he heard.

“I put [Mac and Doc] on assignment to write, and they handed me the whole fucking album,” he said. “And they made these demos that were unbelievable at the piano. I think they did them right there in Doc’s apartment. They were outrageous. It was a gorgeous cassette, man. They were beautiful. I thought these songs were masterpieces.”

But he wasn’t sure B.B. could pull them off. And when B.B. heard the demo, he wasn’t sure he could either. He thought it sounded like a Ray Charles album. Levine agreed. “If you heard Mac’s demos of the songs, at the Wurlitzer piano, phrasing them the way he did, they really did sound like they would have been right for Ray Charles and maybe not right for B.B. A lot of that was just the way Mac sounded. It took me a lot of convincing to get B.B. to agree to it.”

Another problem surfaced: B.B. was, in Levine’s words, “very put off by Dr. John.” Despite having used him on his 1971 In London album, and no matter that the offstage Dr. John was a fairly sedate, and sedately attired, Mac Rebennack, pianist par excellence, B.B., Levine said, “knew him as an artist, and he knew him as a character, but he didn’t really know him as a musician. He was intimidated by Mac.”

Intimidated, as it turned out, by the excellence of Mac’s artistry on the demo tape. As guide vocals (on his recent Levine-produced albums with the Crusaders) he was used to hearing Joe Sample and Will Jennings, untutored singers to put it mildly. When he heard their voices in his headphones during the recording sessions, “they were horrible, and therefore he felt comfortable, because all they were there for was to tell the story,” Levine said. “Now you get demos that are good. Mac makes them sound a little too learned and a little too Ray, and B.B. starts to think they were not made for him. It was a superficial response; at that point he wasn’t even really listening to them.”

Levine urged B.B. to take the demo, go away somewhere, and listen to it alone, absorb it, and consider what he’d do with it.

After a week of silence, Levine got a call from B.B.

“Whatever you think, Stew,” he heard B.B. say. “I’ll be there. I trust you, whatever you think. I don’t know if I can do these. Now I’ve heard ’em and there’s some beautiful words here.”

“‘Beautiful words,’” Levine recalled. “That’s what he said.”

Then B.B. fretted some more. “I’m really worried about it, because he sounds so good doing ’em.”

“About a dozen times,” in Levine’s estimation, B.B. worried aloud as to whether he could pull it off. “He was insecure at that point” is Levine’s assessment of B.B. going into the album sessions at the Hit Factory in New York in November 1980.

There Must Be a Better World Somewhere

MCA, 1981

Produced by Stewart Levine

Musicians

B.B. King: lead guitar and vocals

Dr. John: keyboards

Pretty Purdie: drums

Wilbur Bascomb: bass

Hugh McCracken: rhythm guitar

Horn Section

Hank Crawford: alto sax

David “Fathead” Newman: tenor sax

Ronald Cuber: baritone sax

Tom Malone: trombone

Waymon Reed: trumpet

Charlie Miller: trumpet

Horns arranged by Hank Crawford

Songs

- “Life Ain’t Nothing but a Party” (6:25) (Doc Pomus–Dr. John) alto sax solo: Hank Crawford

- “Born Again Human” (8:31) (Doc Pomus–Dr. John) alto sax solo: Hank Crawford; tenor sax solo: David “Fathead” Newman

- “There Must Be a Better World Somewhere” (5:37) (Doc Pomus–Dr. John)

- “The Victim (6:19) (Doc Pomus–Dr. John) tenor sax solo: David “Fathead” Newman

- “More, More, More” (4:38) (Hugh McCracken–Jay Hirsh)

- “You’re Going with Me” (4:32) (Doc Pomus–Dr. John)

A lilting, minor-key blast of horns, with Crawford’s alto sax murmuring down low as Lucille gets in a few quick cries opens “Life Ain’t Nothing but a Party,” the first song on There Must Be a Better World Somewhere, on a note that recalls nothing so much as the type of arrangement Maxwell Davis had perfected with B.B. long ago. A beautiful intro settles into a mellow groove, and B.B. handles the lyrics tenderly, rising to a growl only near the end, and only for a fleeting effect. The key lyric, “Life ain’t nothin’ but a party/Tomorrow too soon is yesterday/If you live it that way/And don’t give it away/The party still goes on and on and on,” reflects exactly what Pomus meant about bringing a life’s experience to bear on his writing. He had learned to savor that which persisted in his world—the friends, the family, the music he loved—and felt, in his sixties, a sense of triumph over the follies of his younger years. B.B. handled the vocal with the proper avuncular touch, and closed out the song with a sweet, angular commentary from Lucille.

From There Must Be a Better World Somewhere, ‘Life Ain’t Nothin’ But a Party,’ B. B. King, written by Doc Pomus & Dr. John

The same generosity of spirit informs the second number, the eight-and-a-half-minute “Born Again Human,” which kicks off with a three-minute-fifteen-second instrumental intro featuring David “Fathead” Newman blowing a spirited tenor sax solo that sets up another deliberate vocal on B.B.’s part, he entering with the generous sentiment, “You taught me how to bend and never break/You showed me how to give and never take/There was no sacrifice too great for you/Sweet, sweet woman, can’t you see what you mean to me/Born again human…”; at the end he sings, “…through your love/I rejoined the human race.” The track is steady and a bit somber, reflective, drummer Bernard Purdie adding a hi-hat–cymbal flourish here and there, B.B. giving Lucille free rein to moan throughout, and Dr. John settling in below it all with some trebly right-hand blues runs.

From There Must Be a Better World Somewhere, ‘Born Again Human,’ B.B. King, written by Doc Pomus & Dr. John

The thoughtful mood is sustained in the album’s title track, its signature song, a meditation on persistence in the face of adversity, set to the tune of an old hymn Rebennack had heard in his youth in New Orleans titled “This Earth Ain’t No Place I’m Proud to Call Home.” “Flying high/some joker clips my wings/just because he gets a kick/out of doing those kinds of things/I keep on falling in space/Or just hanging in mid-air/But I know, oh yes, I know/There’s got to be a better world somewhere,” B.B. sings with a gospel feel, going on to describe the woes of being mistreated by women along the way, but always coming back to the abiding theme that “there must be a better world somewhere.”

Although not originally conceived as such, the first three songs form a literary and musical cycle, a metaphysical survival guide to getting through the battle, no matter the obstacles. Bad women, bad breaks, a shallow appreciation of the moment—commonplace woes all, but in Pomus’s mature worldview, nothing that a big heart, real love, and a positive outlook can’t overcome. So it’s only fitting that a rollicking song titled “The Victim” should follow this philosophical trifecta. It opens with Dr. John’s rolling piano lick that summons the ghost of Jelly Roll Morton and settles into a stomping groove as B.B. relates a tale of being “a victim of every girl I meet.” Its party atmosphere and Fathead Newman’s intense tenor sax solo provide a buoyant lift to what had been a noirish mood. The album’s closer, “You’re Going with Me,” opens with a thumping round of rhythm courtesy Purdie and Wilbert Bascomb’s prominent ostinato bass riff, and the rest of the band slides into the groove, with a sharp, stinging Lucille solo out front as the horns pump and Purdie stays hard on the backbeat. The whole thing chugs almost to a stop near the end, and then cranks right back up to a brisk shuffle as B.B. intones, “You goin’ with me, you goin’ with me” at the fade.

The only song not composed by Pomus and Rebennack is a co-write by rhythm guitarist Hugh McCracken and Jay Hirsh. Titled “More, More, More,” it’s a gospel-styled hosanna to unbridled self-indulgence, in which B.B. sings of giving up wine and women at age 18, only to return to taking “all I can get.” With an urgent female chorus shouting behind him, he sings of wanting “more, more, more,” and Dr. John rolls off some dramatic arpeggios to heighten the intensity. Philosophically the song is at odds with the Pomus–Rebennack material, but its dark mood seems to suggest that the young man is destined to pay a price for his shameless hedonism—which is more or less the backstory of the album’s opening triptych.

The title track from There Must Be a Better World Somewhere, B.B. King, written by Doc Pomus & Dr. John

The story of the songs and their performance is but part of the tale, however. Levine deliberately stripped down the instrumental support to a basic band to suit Pomus and Rebennack’s narratives. In addition to Rebennack on piano, he brought in the veteran session drummer Bernard “Pretty” Purdie, bassist Wilbur Bascomb (“A pain in the ass,” Levine said. “I didn’t like him, man. He and I had bad tension between us.”), and on rhythm guitar Hugh McCracken, who had first played with B.B. on the Bill Szymczyk–produced sessions in 1969 and 1970. For the six-piece horn section (three saxes, two trumpets, and a trombone) he deliberately sought out and hired two former mainstays of Ray Charles’s band, alto saxophonist Hank Crawford (who arranged the horns) and tenor sax man David “Fathead” Newman. “I rubbed it in with Hank and Fathead,” Levine said, “because B.B. was talking about how ‘Ray’ these songs were. I said, ‘Fuck it, I’m going right into it. He gave me the idea.’ I went and got Hank and Fathead. I just felt B.B. was up to it, to handle that territory that Ray no longer possessed.”

Recording at the Hit Factory in New York, scene of his triumphs with Szymczyk, B.B. fell in with a wild bunch, the likes of which he had never encountered in a studio environment. The troupe worked from eight at night until four in the morning for about two weeks straight, several of the key players laboring under the influence of various pharmaceuticals and libations.

“Oh, what sessions these were, baby,” Levine recalled, at once laughing and shuddering at the memory. “There was a mood about them; I think Doc’s lyrics permeated the air, and that’s one of the reasons the mood was what it was. I think we were all aware of it. My memory is that it was very, very intense, very musical, and very heavy. You can’t say it was a good time. It was serious, you know what I mean? Everyone was at the top of their game, playing as well as they could. But there wasn’t too much communication between people, ’cause Mac was out of it, I was kinda having to be in charge of things and I was drinkin’ too much, Purdie was off in his world. Somehow it all came together. It was dark, and it fit the music, man. Sometimes you gotta make these things make themselves. The mood creates the music. And this record had a real mood. It was just heavy.”

Serving notice that these were not going to be routine dates, Bernard Purdie showed up for the start of sessions without his drum kit. He said he would use the studio’s kit, only to find out the studio didn’t have a full kit. Levine’s mixer-engineer, Rik Pekkonen, found some drums in a closet and set them up. “Purdie hit ’em a couple of times and there it was. Unbelievable. We had nothin’, and we just taped ’em up, put the mics up, and the fuckin’ thing sounded great. It was weird, man; it was a fuckin’ crazy session.”

The lack of a proper drum kit was the least of Levine’s problems. Mac was “a bit of a mess; Mac was incommunicado,” according to Levine. “Mac was fucked up, he was nodding out, and B.B. didn’t really enjoy his presence that much; he just loved the way he played. He was in bad shape.”

It goes on.

From There Must Be a Better World Somewhere, ‘The Victim,’ B.B. King, written by Doc Pomus & Dr. John

“And I was at the end of my alcoholism and for the first time really drinking in the studio. I was drinking three, four, five bottles of white wine a night—and I never even drank wine. It was delirious. Mac was on methadone and mixing it up with other stuff; Purdie was weird; the bass player was weird; Hank Crawford was fucked up, drunk and stoned.” Hugh McCracken was called in not only because of his history with B.B., but because “he was very, very close to Dr. John, and I needed someone in there that could try to keep it going.

“Mac, Hank, and I were basically in the same place, and we were getting along perfectly. Hank and I were gettin’ juiced and gettin’ high, and we were locked in; it was very, very musical. You know what I mean? It wasn’t at all frivolous because we were stoned. I don’t want to say it to make a point of, like, in favor of drugs or alcohol, but it does come to a point where, just ask Charlie Parker and a lot of other people, why the fuck you think they did all that shit? It does zone you in sometimes, and it zones you out other times. But we were on the same level and we were very on the mood. That’s one record I really feel like where we got the tone, the fabric of the songs comes through. And it’s the same old instrumentation. We ain’t got nothin’ on that record. It’s stripped down, very sparse.”

With all this, Levine managed to put to use some lessons he had learned along the way. Early in his career an arranger had told him that a singer should be set up with either an arpeggio or “five minutes.” For the song “Born Again Human,” Levine had the musicians jamming before he started rolling tape. For three minutes and fifteen seconds, it’s a jam, then B.B. enters vocally. “When he comes in, that’s a real jazz record,” Levine said. “The irony of it was that with Hank being around it really wasn’t a jazz band. The joke was that we had the Jazz Crusaders being with B.B. on two albums and we do one thing; then we have Dr. John and these other guys who are not jazz players, and we make what’s essentially a jazz album. It was beautiful.”

The drama didn’t end with the last notes recorded, though. When Levine and Pekkonen arrived at Hollywood Sound Records to mix the album, they found that the high end on the recordings kept going away. Upon further inspection, they found that the oxide was peeling off the back end of the 16-track tapes. “Because it was the blues, we had to stop every 12 bars, clean the tape heads and then mix the next section. We pieced that album together in mixes 12 bars at a time. The whole album. It was a bad batch of tape, and when it went to play, it kept coming off on the heads.

“It was ridiculous. It was one of those records that had pain written all over it, you know?”

Dr. John, a live version of ‘There Must Be a Better World Somewhere,’ the title track he wrote with Doc Pomus for B.B. King’s like-titled Grammy winning album of 1981. Performed on a mid-‘90s French TV show.

Postscript: Levine tells the story of the making of There Must Be a Better World Somewhere with a sense of awe and wonder at what transpired at the Hit Factory in the wee, small hours of those November mornings in 1980. But the message in Doc Pomus’s songs sank in, and once the album was complete he got sober and has stayed that way ever since. “I said, Okay, this chapter’s over, man. I hear what he’s talking about. I better go get it together.”

A year after its release, There Must Be a Better World Somewhere won a Grammy Award as Best Traditional Blues Album. At a party after the ceremony, B.B. wanted to make a champagne toast to his producer. He poured a glass for Levine, who politely declined, saying, “No, B, I ain’t doin’ it anymore. I had to cut it loose.”

Surprised by this revelation, B.B. was rendered speechless for a moment. “Really!” he said at last. “Stew, I didn’t know you had a problem.”

Most of all, Levine took pride in learning that Doc Pomus was pleased with the finished product. Pomus’s daughter Sharyn Felder would later tell Levine that her father considered the album one of the high points of his later life. “I always felt a lot better that Doc thought I was okay,” said Levine, sotto voce. “Made me think I was a little better than I had planned to be, the fact that he thought I was cool and we did justice to this music. Doc was not impressed by much. ‘How are you, Doc?’ ‘Same old shit.’ And he loved this record.”