Michele Raffin with a Blue Crown Pigeon: ‘I admired birds from a distance, but it never occurred to me that they would have personalities, or be very intelligent or possess most of the endearing qualities that we look for in friends.’

History has shown that discoveries made accidentally can prove to be monumentally important on myriad levels, whether it forever alters the landscape on the mankind level or simply changes things for an individual man or woman.

The accident yielding penicillin quickly comes to mind. So does the one that gave us the microwave oven. Those reside on the macro scale.

On the micro level, we’ve heard countless stories of people who were working in a given field and stumbled into showbiz careers.

Marilyn Monroe was working at a munitions plant when a photographer for Yank magazine happened to shoot her picture, triggering the steps that included deciding to take acting classes and dying her hair blond. After that, from what I gather, she made some movies.

On the even more micro level, we all have friends who took a class at one point, or tried their hand at writing while holding down an unrelated job, or started tinkering in the garage, setting into motion a surprising new passion or professional pursuit.

And sometimes, a new avocation or vocation is spurred by an incident wholly unexpected. A curveball.

‘Pretty Mama,’ a short documentary about Michele Raffin and Pandemonium Aviaries

Michele Raffin can relate. She’s the founder and CEO of Pandemonium Aviaries, a Northern California conservation organization dedicated to saving birds that are on the brink of extinction. No one could have predicted this career path, least of all Raffin.

About 15 years ago, she was busy raising her family, working as a Silicon Valley consultant, having received a master’s degree from the Stanford business school.

One day, in the midst of going about her day, she rescued an injured dove that was on the side of the road. Sounds like a pretty innocuous, minor scene.

For Raffin, though, it turned out to be a momentous and truly life-altering incident, as she recalled in a December 3 interview on Talking Animals.

“Well, it was indeed a remarkable time for me, but that’s really in retrospect,” Raffin observed in a conversation partly tied to her recently published memoir, The Birds of Pandemonium: Life Among The Exotic & The Endangered.

“When it happened, I had no idea what was [to come]. We have a very busy highway called the Saint Lawrence Expressway, and I had heard about a hurt bird there on the side of the road. And it bothered me that it would just lie there, waiting to be run over again.

“So I went to look for her, and when I found her, she was indeed injured, and I took her to an avian vet. The vet told me that my assumption that she’d been hit by a car was wrong—that she’d actually been dropped by a hawk.

“And that was one of the very first things I learned about birds that I hadn’t known before. It started a remarkable journey for me.”

More than a few of us, especially if we’re animal lovers, have gone to the aid of an injured bird—one that’s fallen out of its nest, is otherwise hurt or needs help. But doing so hasn’t usually triggered a new career.

So I was interested in why this circumstance played differently for Raffin, why rescuing that bird seemed to resonate more profoundly—and, as it turned out, served as a catalyst for a string of circumstances that forever changed her life.

“Animals in general have always moved me,” she explained, “and the impulse to help this particular animal was no different than helping a lost dog, which I’d done in the past. But what was different afterward was holding that bird, when I took her to the vet, and then visiting her the first few days that she was there, really changed my opinion of birds.

“I hadn’t known anything about them before. I thought of them as pretty when I’d see them in different parts of our garden, and very self-sufficient. I admired them from a distance, but it never occurred to me that they would have personalities, or be very intelligent or possess most of the endearing qualities that we look for in friends.”

Pandemonium Aviaries founder Michele Raffin describes the beauty of the Victoria Crowned pigeon and explains why it is so important to preserve this and other endangered bird species.

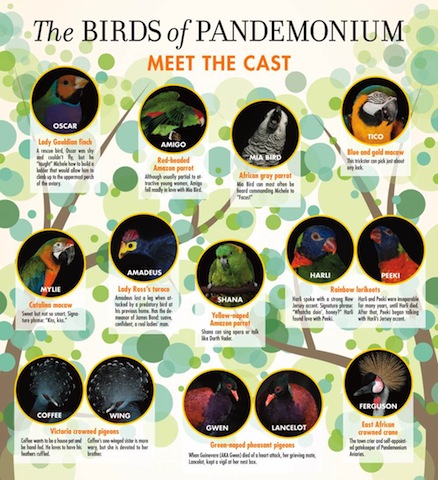

As it happens, Raffin has made a number of those friends. On second thought, a lot of those friends. There are some 360 birds living at Pandemonium Aviaries, which, as has been the case from day one, is located in her Los Altos, California home.

At this point, I think we can safely stipulate that Raffin nurtures a singular passion for birds, and this unforeseen passion was unleashed by what sounds like a garden-variety rescue of an injured dove. May I remind you that she lives with 360 birds?

Why, exactly, is that so unusual? Not the part about living with 360 birds—that, of course, is unusual.

But why do so many regular folks, including those who are otherwise over the moon about animals, feel indifferent to birds? What explains that—what are we missing when we aren’t responding to birds with the warmth and enthusiasm we feel toward other animals?

“I think it’s that we just don’t know them,” Raffin replied. “They’re not domesticated, and even those birds that have been bred to be our pets, really retain the wild in them.

“So unlike the dogs and cats that we grow up with or the horses that we may be familiar with, birds are remarkable and are animals that we just don’t know very well. In this case, to know one really is to love one.

“At least, that’s been my experience… I think what has moved me is how deep birds can be, how emotional they can be, and at the end of the day, really how smart.

“I have dogs and cats and donkeys and goats, too, and birds are way ahead of my other animals in understanding and being able to communicate. In general, they’re very, very smart.”

As she mentions this, I’m reminded that even birds we do see, or at least hear, every day have proven to be enormously smart.

In this conversation with Raffin, I recall the Talking Animals interview with Tony Angell, co-author of Gifts Of The Crow, discussing crows and other corvids’ Mensa-like intelligence in a way that was fascinating.

“It really is. There are a lot of birders in the United States—I think there are more bird-watching people than there are birds,” Raffin said, laughing.

“If we just spend the time to watch a particular bird,” she continued, “quietly and with concentration, I think that we can observe behaviors that indicate that they are more than just pretty things in the garden.

“They love, they mourn, they mate, they sometimes even murder each other. They have very complex emotional lives. Of course, we’ve learned in the laboratory that birds, especially parrots, grasp the concept of zero, they make up language.”

If the realm of feathered friends is far more complex than many of us would’ve have imagined, the milieu of those who breed birds is far more peculiar. Raffin peoples her book with all sorts of wonderful eccentrics, and sometimes, not-so-wonderful eccentrics.

She describes a quirky, colorful subculture where, generally speaking, its denizens are reluctant to share information, are very leery of newcomers. And very, very leery of female newcomers.

So when Raffin first stepped into this world, navigating the territory presented plenty of challenges, and a learning curve steep enough to look vertical. All these years later, though, she sounds philosophical in assessing that land of Ornithological Oz.

“There is a subculture of bird breeders and for the most part, they’re really wonderful people,” she explained.

“But like other groups, they tend to be fairly inbred, and they develop friendships that have been built over many decades. Rare birds are held back from the public, and they’re traded back and forth. And they’re traded based on chits that have been developed over many, many years.

“So if you gave me a bird that I needed 20 years ago, and I have a bird that you need today—even if I’ve already sold that bird, or promised that bird to someone else, I will say ‘I’m sorry, I no longer have the bird,’ and I will give it to you.

“It’s a wonderful reservoir of knowledge. These breeders–a few of them are women, but most of them are men—have accumulated just huge reservoirs of what it takes to keep and breed birds. But unfortunately, they don’t write it down.

“And as they die down, or leave the business—and it is a rapidly aging group—all that information is being lost. We at Pandemonium have a program to really document what these bird breeders have discovered, so that we can use that knowledge going forward.”

Indeed, having survived this screwy society’s extended hazing ritual (“It took many, many years, and breeding a rare bird that none of them had been able to breed to finally get my badge of honor and be allowed into the old boys’ club”), Raffin has not only consolidated that knowledge, but developed her own singular expertise while gradually steering Pandemonium in a different direction.

For nearly the first decade of its existence, Pandemonium functioned as a seat-of-the-pants rescue operation, but about six years ago, Raffin decided to shift the focus to conservation and breeding. (Fun fact: beyond how most of us understand the meaning of the word “pandemonium,” it’s also a term for a group of parrots…a pandemonium of parrots.)

True to form, the organization’s evolution was prodded by a wholly unexpected occurrence—and bird-centric serendipity once again co-writes a pivotal chapter in the Pandemonium saga.

In this case, she recalled in the Talking Animals conversation, it was the death of a bird—a green-naped pheasant pigeon, to be precise—that was the inciting incident. The dead bird’s mate was devastated by the loss, and started crying. “He cried all day and night,” Raffin remembered, “he just sat, wouldn’t eat very much, and just cried.”

She recognized that she needed to find a new mate for the grieving bird, but this turned out to be much easier said then done. “I needed to replace his lost love,” she said.

“But when I went in search and contacted everyone I knew, what I found out is that, in the entire world, there were only 32 green-naped pheasant pigeons left in captivity.

“In the 10 years I had been doing rescue, the world of birds had really changed, and [I realized] that if I really wanted to make a contribution, it had to be more than saving individual birds—it had to be saving species. So really, it was the search for green-naped pheasant pigeons that drove our change.

“I’m happy to say that I did eventually find a mate for him. And Pandemonium now has more green-naped pheasant pigeons than any institution in the world.”

What’s Raffin’s too modest to mention is that Pandemonium’s stature extends a good deal beyond that; the quantity of those pigeons hardly constitutes their only bragging right.

Michele Raffin’s TEDxYouth talk

At this point, the place is considered an internationally prominent breeding facility for avian species facing extinction due to the destruction of their natural habitat.

And amidst a world where the term “conservation” is routinely co-opted by organizations in glib, meaningless ways (like zoos that bandy the word about but implement zero conservation measures), or sometimes downright nefarious ways (the Ringling Brothers Center for Elephant Conservation exists merely to stock their touring circus units with fresh elephants), it’s refreshing and inspiring to see that Pandemonium is engaged in genuine conservation efforts.

And those efforts are carried out in a very methodical, highly meticulous fashion. “We’re very careful,” she said.

“We only have six species that we’re breeding. These are species that have been designated as really important, and frankly, no one else is doing the work. So if we didn’t, I don’t know what hope these species would have.”

But some 15 years after she rescued that injured dove, Raffin is giving these species hope.

And that’s no accident.

Follow this link to the Talking Animals interview with Michele Raffin

About the author: Duncan Strauss is the producer-host of Talking Animals, which he launched at KUCI in California in 2003, combining his passions for animals, radio, journalism, music and comedy. The show has aired since late 2005 on Tampa’s WMNF. Strauss lives in Jupiter Farms, FL, with his family, including four cats, two horses and one dog. He spends each day talking to those animals, and maintains they talk right back to him, an as yet unverified claim.