In the week of January 25, 1975, Carpenters had the #1 single on the Record World Singles Chart in ‘Please Mr. Postman’

The following excerpts are from the forthcoming book, Just Remember: Field Notes from a Music Biz Life.

“It’s bad enough Beer has an MBA. Why does he have to flaunt that fucking map?”–Consensus of record company promotion reps, December 1972

In Lenny Beer’s first 48 hours as Record World‘s Chart Editor, he alienated many of the labels without whose advertising there would be no Record World and therefore no charts to edit.

On Day 1, he taped to his wall that large map of the U.S. highlighting the importance of various markets. On Day 2, he made explicit to the parade of visiting promotion reps what the map had signaled: henceforth our charts would be based on real market research, without fear or favor.

George Harrison displays the November 18, 1974 edition of Record World featuring a fellow named John Lennon on the cover.

The fearlessness came from Lenny’s ignorance of the consequences of not doing favors.

The label execs were dumbfounded–and furious they might lose the leverage they believed their ad dollars ought to have guaranteed. When they felt they didn’t get a fair hearing from Lenny, who was long on smarts but short on diplomacy, they came to me.

Some argued against the new policy, others just vented. A 20-something master of understatement from CBS Records cautioned against charts “wound a bit too tight.” A more seasoned rep from United Artists lobbied for a transition period of a few months so Lenny could learn “how the business really works.” Atlantic’s ageless Juggy Gayles, the man who, we liked to say, put the “hype” in “hyperbole,” was more direct: “Fuck his fucking MBA, just give me my bullets.”

Comic relief came courtesy of a rookie rep from London Records, who barged into (our publisher) Bob Austin’s office and demanded Lenny’s head. Bob, who operated in a timeless realm far removed from the quotidian concerns of the magazine, had no idea we were changing anything. He flicked the rep over to me, figuring we peons would hash it out. We didn’t hash, and London stormed out.

If Lenny cared too little about what others thought, I cared too much. In each meeting I asked for time and forbearance. But I could only use generalities in defending Lenny because I didn’t know the details about his new methodology. Neither did he, yet.

* * *

Feeling restless at the end of a long, dark Tuesday, I decided to jog home from our midtown offices to my West Village apartment, a trek that seems insanely dangerous in retrospect. Propelled by nervous energy, I dodged the jaywalkers, the buses and the taxis but ran smack into a wall of anxiety. That one of our owners was clueless about the magnitude of what I’d set in motion suddenly didn’t seem funny. How would he and his partner Sid Parnes react when the chart bullets stopped flying?

Lenny was like a blank slate falling off a turnip truck into a vacuum. No system existed at Record World for compiling charts, and he didn’t know a rack jobber from a one-stop from a distributor.

The good news was that since there was no system to overthrow, he had complete freedom to innovate. And blissful ignorance of the old boy network of record company honchos, retail mavens and radio programming cliques that ran the business made it hard to play favorites: If you didn’t know whom you were offending, you wouldn’t need to play defense.

To find out and report the truth about which records were headed for the top and which were destined to fail was a lofty goal. But we weren’t completely idealistic: Amazingly enough, even in 1972 such a system didn’t exist anywhere. Most records were ranked pretty similarly in Billboard, Record World and Cash Box. But too often they were separated by huge margins that could be explained only by ineptness or corruption. Or both.

Our goal was to publish the No. 1 charts in the industry–No. 1 with a bullet.

***

The first order of business was to create a transparent set of rules and procedures for determining and reporting how albums and singles were ranked, how they moved up and down and how bullets were awarded or denied.

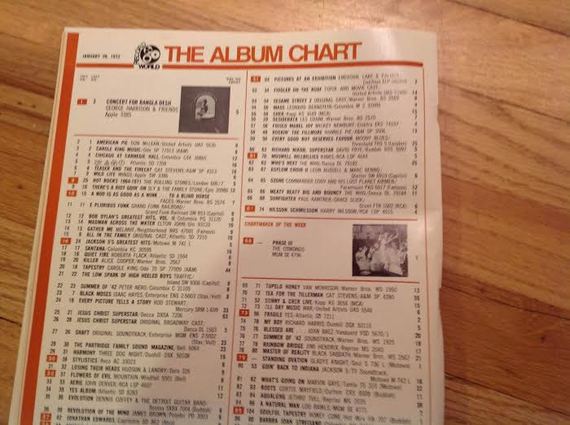

Albums

Album charts in all the trades were based solely on sales. In those days of manual typewriters, no voice mail and no fax machines, some retailers were contacted by phone, but most reported via snail mail, which by definition made them hopelessly out of date by the time the trades hit the streets. They’d generally say that sales on a given album were “Good,” “Bad,” or “Poor.” Or they might give you their Top 10; or their Top 40.

Drawing conclusions from this kind of information was artistically–and perhaps financially–satisfying, but mathematically absurd.

Say Tower Records ordered 100 units of a Rolling Stones album in four cases of 25. If they sold two cases, that’s 50 out the door. Then say that same buyer ordered five copies of Foghat’s LP and sold out fast, so he ordered another five and immediately sold those. He might report that the Stones album was “slow” or “bad” but that he’s having trouble keeping the Foghat in stock! In reality, he sold 50 copies of the Stones and only 10 of Foghat.

An even more fundamental reporting flaw rendered the existing album charts irrelevant: most surveys reflected shipments of albums to stores, not actual sales to consumers.

One label might ship 500,000 (earning a Gold certification) or even one million units of an album (Platinum) and debut in the Top 10—-but end up selling only 50,000 and the unsold copies would have to be returned. (Hence the joke that an over-hyped record “shipped gold and returned platinum.”) Another album that shipped 50,000 and sold every last copy would barely make the charts.

If it seems obvious now that you can’t have an accurate album chart unless you track legitimate sales–aka “piece counts”–consider that it’s also obvious now that the earth is round.

Gary Cohen, another RW staffer in his early 20s, had worked at Queens retail outlet Disco Disc when he was 19, giving him more retail experience than the rest of us combined. A workhorse who prided himself on being the first into the office every day, Gary spoke retail. He got the gossip about the movers and shakers in the retail community, he wrote front-page stories about them and he gained their confidence. After a while, they began giving him the all-important piece counts.

Record World found an early ally in Ira Heilicher, the hip young son of industry titan Amos Heilicher, whose Minnesota-based company owned the 1300-store Musicland retail chain and was the leading rack jobber in the nation. (Rack jobbers were wholesalers who bought in bulk and supplied retail stores with “racks” and product.) At their peak, the Heilichers were responsible for a fifth of all records sold in the U.S.

Ira understood that his company, and everyone who made money selling records, could benefit directly from charts based on over the counter sales. Accurate information about the current status and, more important, the future trajectory of records, facilitated smarter bets on what to purchase and in what quantities. And that meant higher profits.

(from left) Lenny Beer, Toni Profera and Ira Heilicher, circa 1973

Ira became the first retailer to give us piece count data. But he did much more than that: once the Heilichers were on board, Ira lobbied others, including the rack jobbing giant Handleman and the innovative retail chain Record Bar, to follow suit

Singles

While the album charts were determined by a straightforward projection of piece count data, the singles charts–a combination of Top 40 radio airplay and sales–were more of an art form.

Based on a formula that Lenny called “a constantly moving matrix”–a market-research phrase that deeply annoyed the street-hustlers–the criteria for upward movement/bullets shifted from week to week due to such variables as the fluctuations of stations’ ratings and the weight given to sales versus airplay. If a single went Gold without huge airplay was it a bigger smash than one that sold fewer copies but dominated the nation’s airwaves and sparked monster LP sales?

To nail the airplay part of the equation, it was essential to know not only which records were getting played by the nation’s bell weather Top 40 stations but which records were working, which records were exciting listeners enough to merit heavy rotation.

With that information as a foundation, a chart could not only capture where a record stood at a particular time but also–far more significantly–could predict its future trajectory.

Powerhouse radio programmer Scott Shannon proved to be the Ira Heilicher of singles. Understanding that singles charts with strong predictive powers could help stations achieve higher ratings and increase profits, he smoothed the way for us with other key players.

Scott Shannon

With Gary Cohen in place on the retail side, Lenny turned to an even younger staffer to liaise with Top 40 radio movers and shakers. Toni Profera started at the RW reception desk fresh out of high school–she had experience talking to people!–and her likability and attention to detail had earned her a spot in the chart department shortly before Lenny’s arrival.

Toni quickly became the point person in developing long-term mutually beneficial relationships with such programming luminaries as Les Garland, Dave Sholin, Bob Pittman, Rosalie Trombley, Marge Bush, Randy Kabrich, Steve Rivers, Jim Smith, Rochelle Staab, Don Benson and Joel Denver.

***

The 48-hour revolt against Lenny and the brave new world of accurate charts was harrowing. But there had been no direct threats or specific reprisals. The threats didn’t start until Wednesday. The reprisals took another week.

(More about the chart wars in later chapters. Next: Special Issues, starring The Who, Elton John, The Bee Gees, and Glodean White’s fingernails.)

***

The Who’s 10th Anniversary, 40 Years Later

By Michael Sigman

In early 1973, shortly after I took over as editor of Record World, a mysterious package from our Latin American Headquarters in Miami–aka the apartment of our sole employee in that city–appeared on my desk. I opened it to find a jumble of single-spaced typewritten pages, a small stack of checks, photos of Nelson Ned, Tito Puente and other Latin luminaries, a wad of cash, a Fania Records logo, and a slew of crude ad layouts. The copy, which bore the introduction, “First in Spanish and then in English,” was spiced with sentence fragments, glaring typos and randomly placed exclamation points (something about “a concert! At Madison! Square Garden”).

A jolt of angst stabbed me in the gut and spiraled brainward; there was no way to make this publishable. I relaxed a little when Sid, our co-owner, arrived just before noon in good form–in other words, not drunk. Maybe he’d agree to send the mess back to Miami for a do-over. Sid’s sober response made me wish I were drunk: He rummaged through the checks, stuffed the cash in his pocket, and said, “It’s a special. Run it.”

At that time Record World was only marginally profitable, and Sid never looked a gift horse in the mouth, regardless of what tongue that mouth spoke.

Unlike our deep-pocketed competitor Billboard, with its healthy mix of worldwide subscribers and strong newsstand sales, the overwhelming majority of Record World’s revenue came from advertising by just a handful of major labels–CBS, WEA (Warner/Elektra/Atlantic), MCA, RCA, and Capitol–and a dozen or so indies, including A&M, Roulette, Brunswick, Buddha, and Bell.

And there was more than money at stake.

Ads made us look good. A thick book (that’s what we call magazines in the business–a book) larded with lush four-color spreads featuring album covers that were often themselves works of art broadcast success. Which bred more success. More important, we purported to tell the story of what was happening in the trade, and trade ads were unfiltered signifiers of who was hyping what and how aggressively.

With Lenny Beer’s revolution in the charts making some labels see red, we had to broaden our ad base to stay out of the red. We doubled down on that time-honored trade magazine cash cow, the special issue.

Except for a higher print bill, a little extra in mailing, and increased sales commissions, it cost roughly the same to produce a 128-page special as a 64-page regular issue, with two or three times the revenue. The pressure from Sid to do more and more of them was intense.

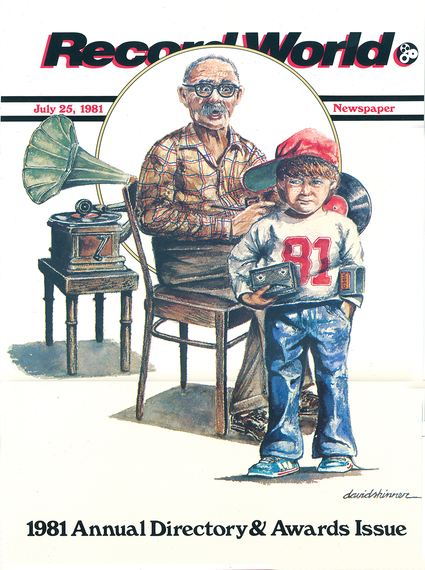

Our most reliable special, the summer “Annual,” was an ode to tedium. It was nearly as thick as Vogue’s Fall Fashion issue, but there were no stunning supermodels or fabulous clothes–just the names and addresses of thousands of rack jobbers, one-stops, distributors and other participants in an industry infrastructure that few, including most of our own writers, understood or cared about.

What saved our Annuals from drowning in minutiae were the covers, such as this Norman-Rockwell-with-a-twist gem from art director David Skinner:

The Midnight Special TV show! The content tended towards puffery and the ads turned out to be tough sells. You might think it was groovy that lots of women were having hits, but why would you need to advertise about it?

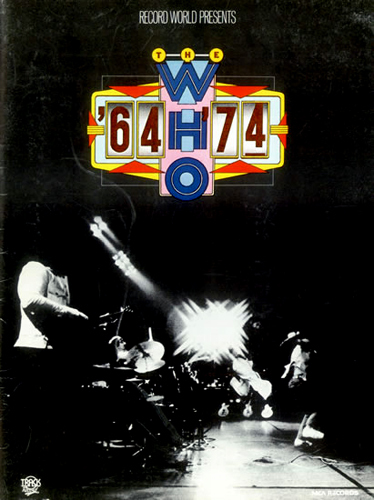

The turning point, both editorially and financially, was our 10th Anniversary tribute to The Who in November, 1974.

That we were chosen over Billboard to tell the story of my favorite band seemed too good to be true. What it took to tell that story nearly broke me.

My obsession with The Who began in 1964-65 when I was 15 and their singles “I Can’t Explain” and “My Generation” explained why it was impossible to explain my generation to myself, let alone my parents.

The perfectly interlocking musical personalities of the four members–the funny-looking/rebellious/guitar-smashing/ leader/songwriter Pete Townshend, the great-looking/passionate/ golden boy vocalist Roger Daltrey, the brilliant, enigmatic bassist John Entwistle and the gloriously chaotic drummer Keith Moon–were the very illustration of a whole that was greater than the sum of its parts.

The Who’s subsequent string of ’60s hits–“Happy Jack,” “The Kids Are Alright,” “I Can See for Miles,” “Pictures of Lily”–were as essential to my teenagery as basketball, my guy friends and my lack of girlfriends. Their 1967 concept album The Who Sell Out, was a hilarious, prescient satire on consumer culture.

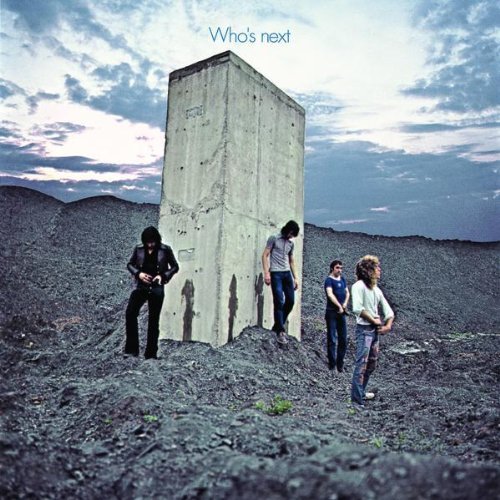

By the time I graduated from college and started at Record World in the summer of ’71, the Sixties were gone and Carole King’s Tapestry had become the founding document of the era of the softer singer-songwriter. Who’s Next, released that August, was a defiant declaration that The Who hadn’t sold out and that biting, meaningful rock ‘n’ roll was alive and kicking out the jams.

Who’s Next was a great record, but The Who were at their core a live band, and their performance at Forest Hills Stadium that summer was the most thrilling show I’d ever seen.

The Who, ‘Magic Bus,’ live at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium, New York, July 29, 1971–15th and final song of the set.

A burst of rain threatened to cancel the concert, but the skies cleared and the group blasted through one masterpiece after another, building to a driving “Magic Bus” that would have blown the roof off the place if the place weren’t outdoors. Townshend put an anti-ribbon on the proceedings by smashing not just one, but two guitars, after which he decimated those instruments with a third piece of equipment.

Needless to say, no encore was necessary–or, given the destruction on display, even possible.

Record World‘s West Coast Ad VP Spence Berland, a transplanted New Yorker and a natural salesman who could get you to buy an ad even if you didn’t want one and had no money, convinced The Who’s brain trust to give us exclusive rights to publish a special commemorating the group’s 10th anniversary.

Quite a coup, considering Billboard‘s international reach. Spence also enlisted MCA Records, The Who’s label, to help us score “Congrats” ads from the label’s distributors and the band’s friends and associates. The resulting bonanza meant lots of room for editorial coverage, a good thing because there was a big story to tell. It also guaranteed a boatload of extra work for me and our small staff.

Putting out the weekly magazine–and dealing with industry politics–was stressful enough; I’d become prone to anxiety attacks, bouts of insomnia and nasty lower back pain.

Knowing that my workload would spike for the next couple months added a simmering anger to the mix. I was mad at the gods for making me work so hard, mad at Sid for not paying me and the writers better, and mad at Spence who, working on commission, earned more than the top three editors combined. I was even mad at our writers for expecting me to be nice to them while I was doubling their workload without bumping up their salaries.

Anxiety and anger notwithstanding, we threw ourselves into producing an issue worthy of The Who. I was too consumed with planning and editing to interview my heroes, but between our New York, LA and London editors–and Who experts including John Swenson, Marty Cerf, Greg Shaw and Binky Phillips–we told a compelling story.

The trick in avoiding hagiography in a special was finding the quirk. Here, that was easy–Keith Moon was the quirk that kept on quirking. We wrote about the time he got arrested for a gold bullion robbery because, well, because he was Keith Moon. (He didn’t do it.) One advertiser was clearly thinking of Keith with this copy: “…without whom Holiday Inns and Remy Martin may never have survived…doesn’t time pass quickly when you’re having fun.”

This year it’s The Who’s 50th anniversary. One wonders what Pete Townshend, who famously wrote in “My Generation,” “Hope I die before I get old,” would say about this quote from his RW interview: “The great thing about rock is that it makes you feel young.” Or what Roger Daltrey would think of this remark: “There’s no chance of us ever breaking up.”

The Who will embark on an epic “Who Hits 50” tour next spring. Maybe they’ll make one more record and call it, Who’s Counting?

* * *

Our book–the regular issue and the 92-page pull-out special section–had to be press-ready by Friday afternoon so it would land on subscribers’ desks by Monday morning. The 72 hours before that deadline were pure hell.

Along with RW associate editor Howie Levitt–a terrific person and a fine editor with whom I shared a Long Island upbringing, a love of rock and sports and a post-hippie sensibility–I spent nearly every one of those hours at Dispatch Press, our printer, whose desolate location in Hoboken, New Jersey–when Hoboken wasn’t cool–came to reflect my mood.

The Who, ‘The Kids Are Alright’

Our writers had knocked themselves out to get their stories in on time, but Sid insisted we keep the ad window open till the last minute, which was good for the bottom line but torture for Howie and me.

With more ads pouring in–which taxed our art department to its limits–I had to keep increasing the page count, and we ended up laying out–and re-laying out–hundreds of pages using the primitive implements available to us at the time: cutting out reams of paper galleys with scissors, then Scotch Taping them to cardboardish “dummy” sheets. Then tearing them up and doing it again.

The irresistible force of Sid was matched by the immovable object of Ray Stein, who ran Dispatch and, as Wednesday turned to Thursday, began to freak out. Ray was a solid guy, and when he warned that if I didn’t start feeding him finalized pages he simply wouldn’t get the magazine out on time, I believed him.

Sid argued that Ray was crying wolf but Sid had never been to Dispatch and didn’t know what he was talking about. Shaking with rage, I told him that our production crew and proofreaders were on their way and I didn’t have pages to give them. I told him it was panic time.

Sid relented and we broke our backs and made deadline. Another hour and someone would have had to arrest me for verbal abuse. Another two hours and murder might have been a more appropriate charge.

The special hit the streets on schedule and turned out fine. No, it turned out wonderfully. My state of mind–and, not coincidentally, the tone around the office–had swung from dread to relief. More to the point, we were proud of what we’d accomplished.

Before leaving for the day, Howie gently pointed out that he and other staffers felt I had been uncharacteristically short with them while we were on deadline. I knew that was an understatement and felt awful about it, but instead of apologizing, I played the victim. The pressure had been on me, I said, and everyone should get off my case.

I recalled that that my anger had found another undeserving target when, late the previous week, a publicist called to say she was coming over to deliver a press release. I screamed, “Who cares?” and fantasized about naming the special Who Cares?

The Who issue wasn’t just a turning point for Record World. It was a turning point for me. I began to be more assertive in “managing up”–insisting, for instance, that Sid agree to more reasonable ad deadlines for future specials. I was more mindful about not taking my frustrations out on others, especially the amazing people who worked for me. And I vowed to be more open to criticism, a vow I would forget from time to time in the heady, stress-filled years to come.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Michael Sigman is a writer, editor, publisher and media consultant and the president of Major Songs, a music publishing company that handles the catalogs of his late father Carl Sigman and several contemporary songwriters.

While still in high school in Great Neck, L.I., Sigman worked for music publishing giant The Richmond Organization cataloging the music publishing giant’s vast catalogue of pop, folk and rock songs. During the summers between college semesters at Bucknell, he worked as a reporter for Record World magazine, a leading music industry publication. The day after he graduated (Magna Cum Laude/Phi Beta Kappa) from Bucknell, he began full-time work at RW and served as the magazine’s editor from 1972-82.

After a year as a consultant for CBS Records, Sigman moved to Los Angeles in 1983 to become the publisher of LA Weekly, the nation’s largest alternative newsweekly, where he served from 1983-2002. He was also the founding publisher of OC Weekly, sister paper to LA Weekly, when it was launched in 1995.

Sigman’s writing has appeared in Record World, LA Weekly, the L.A. Times, OC Weekly, The District Weekly, LA Style, The Bluegrass Special.com, Record Collector News, LA Progressive, Deep Roots and other newspapers and magazines. He is also the author of a biography of his father. He currently writes a weekly blog for Huffingtonpost.com.