https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_tJ5z9EaKWI

Director: Busby Berkeley

Producer: Benjamin Glazer (associate producer), Hal B. Wallis (executive producer)

Screenplay: Sig Herzig (screenplay), Bertram Milhauser and Beulah Marie Dix (from a novel by)

Music: Max Steiner

Musical Director: Leo F. Forbstein

Orchestrator: Hugo Friedhofer

Cinematography: James Wong Howe

Film Editing: Jack Killifer

CAST

John Garfield (Johnnie)

The Dead End Kids: Billy Halop (Tommy), Bobby Jordan (Angel), Leo Gorcey (Spit), Huntz Hall (Dippy), Gabriel Dell (T.B.), Bernard Punsly (Milt)

Claude Rains (Detective Phelan)

Ann Sheridan (Goldie)

May Robson (Grandma)

Gloria Dickson (Peggy)

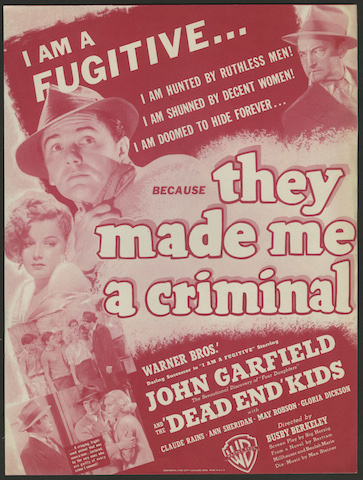

In this impressive remake of a winning 1933 film titled The Life of Jimmy Dolan (starring Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.), Johnnie Bradfield (John Garfield), a deadly and cynical prize fighter, has just slugged his way to the championship when, during a drunken brawl in his apartment, his manager, Doc Wood, accidentally kills Magee, a newspaper reporter, and fixes the evidence so it appears that Johnnie has done the deed. Doc then makes his getaway, but perishes in a car accident while wearing Johnnie’s watch. The next morning, Johnnie awakens in a strange place and reads a newspaper article informing him that he has perished in a car wreck after murdering a reporter. On the advice of a shady lawyer, the champ flees, changes his identity and becomes an outcast. He lands in Arizona, where he casts his lot with Grandma (May Robson), who runs a date ranch with the help of Peggy (Gloria Dickson) and the Dead End Kids (later to become the Bowery Bows, no less mischievous but no longer juvenile delinquents), now under contract to Warners after their co-starring debut in MGM’s Dead End, with Humphrey Bogart. The Kids have been sent from New York by a kindly priest who wants to rehabilitate the boys. At the ranch, the regeneration of the boxer begins as Peggy helps him to fight his inborn tendency to believe that everyone is a sucker and the world has it in for him. Johnnie’s salvation comes when he enters a local fight ring to win some money so that he can help the kids open up a filling station. Meanwhile, New York Detective Phelan (Claude Rains) cleverly picks up Johnnie’s trail and tracks him to ringside where he is fighting a heavyweight. As Johnnie slugs his heart out for his friends, Phelan begins to reflect and, realizing that the fighter has been punished enough, returns to New York without his prisoner.

Claude Rains (Detective Phelan) homes in on John Garfield (Johnny Bradfield) and Gloria Dickson (Peggy) in They Made Me a Criminal

Look for Ward Bond in a smaller role here—he plays the boxer who goes in the ring with “The Bull” right before Johnny/Jack. He does a nice job with the part—in fact, he nearly steals the limelight in his scenes, tugging at the heartstrings with the nervousness he was trying to hide.

Also, in a scene in which Bradfield/Garfield takes a sort of shower, thanks to the Kids’ assistance, one of the Kids warbles an off-key version of “By a Waterfall,” the Sammy Fain-Irving Kahal song featured in an incredible sequence Berkeley choreographed in the 1933 musical Footlight Parade. By 1939 those musicals were passé and Berkeley was into a career of straight directing, but clearly the memory lingered on and was worth tweaking.

They Made Me a Criminal marked Garfield’s first starring role in a film. As the first Method actor to become a movie star, Garfield’s training shows in the quiet understatement of his performance, and in his avoidance of the scenery-chewing Edward G. Robinson and James Cagney had done in similar parts in earlier Warners films. Had he not died of heart problems in 1952 at age 39, he would have starred in On the Waterfront, in a part originally intended for him that instead became one of Marlon Brando’s signature film roles.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=csG6MBYsmOU

‘By a Waterfall,’ from Footlight Parade (1933), sequence with Dick Powell, Ruby Keeler and the Chorines, directed by Lloyd Bacon, choreographed by Busby Berkeley on one of the largest sound stages ever built, constructed especially by Warner Bros. in order to film Berkeley’s outsized creations. Sensual and surreal, this is one of Berkeley’s most dazzling creations, replete with breathtaking overhead kaleidoscopic shots in which bodies are transformed into serpent and spermatozoa shapes, erotically charged water ballet and incredible underwater routines featuring a bevy of beautiful dames in flesh colored bathing suits, some of which leave little to the imagination. Song by Sammy Fain and Irving Kalahl. In addition to Powell and the ever-lovable Keeler, the movie stars a frisky James Cagney, Joan Blondell, Frank McHugh, Guy Kibbea, Ruth Donnelly, Claire Dodd and Hugh Herbert. Not the finest quality clip, this, but the only one available of the entire amazing scene.

Shot from the “By a Waterfall” sequence, choreographed by Busby Berkeley, in the film “Footlight Parade” (WB, 1933). From the collections of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research.

In analyzing what he calls “the most stunning scene choreographed by Busby Berkeley,” Paris-based critic Justin Erik Halldór Smith observes: “Berkeley’s choreography is best known for its complex architecture, rather than for its ‘moves.’ He was more an architect than a choreographer, in fact, and what he achieves in the end cannot really be called ‘dance’ at all. The raw material he works with is women’s bodies, and his oeuvre shows a singular obsession with turning these women into geometrical patterns. Once this aim of his work is grasped, it is hard to think of it as light entertainment. I don’t know enough about him to say what was driving this obsession, but I can’t help but be reminded of the well-known aim of 18th-century French gardening: contrôle totale du monde végétal. Replace the vegetal with the feminine and you have a fairly good summary of Busby Berkeley’s art.

“Berkeley’s architectural choreography is made possible through the intervention of a third art–cinema–and the choreographed scenes, taken apart, suggest to me a possibility for the history of cinema that largely died out with Dziga Vertov and only lived on on the avant-garde margins in the work of such film-makers as Stan Brakhage: namely, cinema as principally a visual rather than a narrative art, whose objective is to capture transient patterns in the world. There is nothing more transient or unstable than a geometrical assemblage of women, but Berkeley understands how to use film in order to effect an incongruous, indeed impossible, transformation, and to make it, in a sense, permanent: he freezes these unstable moments in time during which organic bodies are reduced to simple and regular shapes.”

The Star-Crossed Life of Gloria Dickson

In They Made Me a Criminal the female lead, Peggy, is played by the ill-fated Gloria Dickson. Born Thais Alalia Dickerson in Pocatello, Idaho, on August 13, 1917, her film debut in 1937’s They Won’t Forget had put her on the fast track to film stardom, landing her on numerous magazine covers and leading to a fruitful second career as print model sporting the latest fashions in newspapers and magazines. In turn, critics began referring to her as “Hollywood’s most perfect blonde.” No airhead starlet, she cited Sinclair Lewis and Charles Dickens as her favorite authors, and absorbed the essays of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Elbert Hubbard along with Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. In June 1938 she married a famed Hollywood makeup man, Perc Westmore, who is described on the website glamourgirlsofthesilverscreen.com as “a notorious womanizer and partygoer” and “very controlling and jealous.” Tinsel town columnist Paul Harrison was on the set of They Made Me a Criminal and filed the following anecdote about a scene he witnessed: “I found that a window in one of the walls built on the sound stage offered the best view of a scene being played by John Garfield, Gloria Dickson and some of the Dead End kids. Soon I was joined by Perc Westmore, head of the makeup department and husband of the actress. We watched several unsuccessful takes of a different scene that was supposed to end in a tender cinch between Miss Dickson and Garfield. The latter finally came to the window and said, ‘Perc, please get away from there. I can’t make love to a gal while her husband is peeking though a window at us.’ But Westmore wouldn’t move. We both moved, though, when an irate cameraman told us we were in the scene. And sure enough we were—reflected by a mirror on the opposite wall of the set. If any of the earlier takes had been approved, astonished audiences would have noticed a couple of complete strangers peeking through a window and smirking at a heavy love scene. Westmore told me later that he wasn’t in very high favor with his wife anyway. Before going on a recent vacation trip, Miss Dickson wrote an order assigning him the exclusive right to collect her pay check. Returning a couple of weeks later, she discovered that she couldn’t collect her own money; the assignment was irrevocable except with his consent. And, for a gag, he has refused to surrender the letter.”

The tumultuous Dickson-Westmore marriage ended in 1949, when she filed for divorce following a bizarre missing persons scandal set off by Westmore following his wife’s departure on a personal appearance tour of the East, which featured a report of her having an affair with actor-musician “Ukulele Ike” Cliff Edwards [later to gain a measure of immortality as the voice of Walt Disney’s Jiminy Cricket], which Ms. Dickson adamantly denied). To Paul Harrison she explained: “I shouldn’t have married him in the first place. It was just one of those things. Perc was having trouble arranging his material for a radio show, and I knew quite a bit about radio, and I helped him, and we went on from there. I felt he needed me, and I’m the sort or person who has to be needed.”

Harrison added: “She still is upset over his publicity stunt of having her reported missing. While the story was breaking, he was telephoning her frequently in Pittsburgh.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vd7mUdBinPw

Gloria Dickson (as Mona Verdivere) confronts Rudy Vallee (as Terry Moore) in 1938’s Gold Diggers in Paris (choreography by Busby Berkeley)

By this time Dickson’s once promising career was on the skids, with one failed film after another, along with a second failed marriage (to director Ralph Murphy) and a drinking problem that took a toll on her looks as her weight soared. Regrouping, she stayed sober and regained her figure (a Hollywood gossip columnist reported he had seen her “minus 12 pounds and looking swell, at Charley Fox’s”), and married for a third time, but happily, to ex-Marine/former Jean Harlow bodyguard William Fitzgerald, and began making plans to go back to work. On April 10, 1945, shortly after 2 p.m., a neighbor saw flames roaring from the front and the roof of Dickson’s Hollywood house. Five fire departments were summoned to the scene; Fitzgerald arrived in a panic and tried to enter the house. “My baby’s in there!” he screamed. “I’ve got to get to my baby!”

Dickson’s body was found face down by a bathroom window. An autopsy revealed she died of asphyxiation from inhalation of flames that seared her lungs. She suffered first- and second-degree burns over her entire body. Her lifeless pet boxer was found a few feet away.

Gloria Dickson and John Garfield off the set of They Made Me a Criminal. In the January 2, 1939 issue, LIFE Magazine, Oliver Hotspurwrote of Ms. Dickson: “This breathtaking morsel of feminine loveliness, this surpassing goddess of men’s dreams, is Hollywood’s idea of the ideal Movie Star.” He went on to describe her looks as being shaped by Perc Westmore from “parts of four real Warner goddesses: the hair of Gloria Dickson (Mrs. Perc Westmore), the nose of Olivia de Havilland, the lips of Ann Sheridan and the eyes of Priscilla Lane. This composite Venus would be worth at least a half a million dollars a year—if she could act.”

Apparently an unextinguished cigarette ignited an overstuffed chair on the main floor, while Dickson napped upstairs. The upstairs windows were too high to reach, and she tried to escape through the small bathroom window, but was overcome by smoke. She may have waited for an hour in the bathroom to be rescued. At her death she was 27 years old.

Gloria Dickson is interred at Hollywood Forever Cemetery, Section 2, Lot 18. She rests beneath a shady tree; her marker reads, “Thais A. Dickerson, My Baby, 1917-1945.”

In 1950, while working as a long-haul truck driver, William Fitzgerald was arrested for desertion in time of war and served time in a military brig in Plattsmouth, New Hampshire. He was dishonorably discharged in 1950. Arrested in 1955 after writing a series of bad checks, he was sentenced to five years in the Nebraska State Penitentiary, where he died at age 47 in 1958 from complications of venereal disease. His unclaimed body is buried in the prison cemetery.

SELECTED SHORT SUBJECTS

‘HOW WALT DISNEY CARTOONS ARE MADE’ (1938)

A Trip Through the Walt Disney Studios was a documentary made in response to requests from members of RKO Radio Pictures for a behind the scenes look at Walt Disney Studios. The film was never intended for public showing; it was only shown to executives at RKO. However, footage from this documentary was recycled into a shorter featurette, How Walt Disney Cartoons Are Made, which was released to public audiences. It was shot in the first week of July 1937.

The film opens with the Walt Disney Studios sign with Mickey Mouse on it. The camera then pans over to the studio building and parking lot. Before the tour, Walt Disney is at his desk with a snappy outfit with a tie and a boutonniere, with a baby photo of him on the left, and models of the dwarfs on the right and right next to him is lifelong secretary, Dolores Vought. At the end of the documentary, Walt is at his desk with action figures of the seven dwarfs, explaining the origin of each name.

When you see the legendary animator Fred Moore draw Mickey Mouse, he is using a grease pencil instead of a normal lead pencil, because drawings with thin pencil lines wouldn’t photograph well.

Some of the other Disney Studio stalwarts seen in the film include, but are not limited to, Norm Ferguson, Webb Smith, Jack Kinney, Hamilton Luske, James MacDonald, Les Clark, Frank Churchill, Leigh Harline and Oliver Wallace.

The film can be found on the DVD set Walt Disney Treasures: Behind the Scenes at the Walt Disney Studio. It was also present (along with How Walt Disney Cartoons are Made) on the 2001 DVD release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the film being portrayed in the documentary. (Source: Wikipedia)

‘GOOFY AND WILBUR’ (1939)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JWydAPXe5FU

Goofy and Wilbur was produced by Walt Disney Productions and released by RKO Radio Pictures on March 17, 1939. It was the first cartoon to feature Goofy in a solo role without Mickey Mouse and/or Donald Duck. Here Goofy goes fishing with his pet grasshopper, Wilbur, only to experience persistent bad luck. The cartoon is notable for its high level of japery throughout, and its remarkable sequence of 13 consecutive pratfalls.