Morgan Kingston: ‘I believe strongly that a singer cannot adequately express the beautiful and pure in music while cherishing at the same time a bad heart and a mean nature behind it. Singing is such a personal thing, that one’s mentality, one’s inner nature, is bound to reveal itself.’

The following chapter is taken from Harriette Brower’s 1917 book Vocal Mastery: Talks with Master Singers and Teachers. Though many of the artists Ms. Brower chatted with in her book are now obscure (apart from Caruso, many would be almost totally lost to history but for the research by fans and historians such as Ashot Arakelyan as posted on his essential blog Forgotten Opera Singers), they were in their day among the most prominent in the classical field. One of Ms. Brower’s subjects was the tenor Morgan Kingston, born Alfred Webster Kingston at Sparrows Forge, Wednesbury, Staffordshire, a market town in England’s Black Country. The son of a coal miner, he rose through the ranks to share the stage at the Metropolitan Opera with Caruso in an acclaimed turn as Manrico in Il Trovatore.

In his youth Alfred’s family moved to Beardall Street in Hucknall, Nottinghamshire. At ten years of age, Alfred followed his father down the pit at Hucknall Colliery but spent his leisure hours in music with the St. John’s Church choir and later with the Byron Quartette, which included his brother William and two friends, William Holland and H.G.M. Henderson.

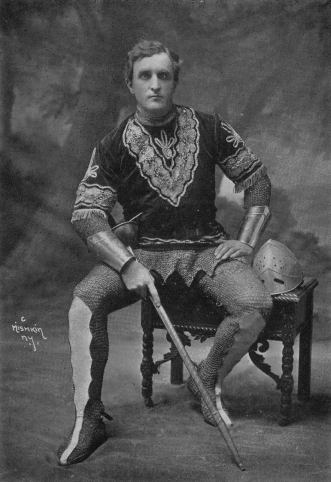

Alfred married in 1895 and moved to the newly sunk Crown Farm Colliery in Mansfield where his colleagues clubbed together to send him to London two days a week for speech and singing lessons with Hugo Hinds. The Rev. Stainer of Warsop Church, impressed with his singing, arranged for Alfred to have permanent lessons in London with Evelyn Edwardes. In 1909 he made his first appearance under his stage name of Morgan Kingston one Sunday at the Queens Hall in London and continued these appearances whilst still working at the pit to pay his way. A tall athletic man with a good stage presence, he was singing more and more at the important festivals of the day. In 1912, he was heard at a concert by Campini and Dippel and was engaged to perform with the Chicago Philharrnonic Opera but Dippel then moved to another company and Morgan found himself singing with the Century Opera Company. He successfully sang in Lohengrin, Samson and Delilah, La Boheme, Tosca, Pagliacci and Carmen–all in English, the normal policy of the Century Opera Company though he had mastered French, Italian and German. He could take the tenor role in 50 different operas.

In 1913, Kingston sang at the White House for President and Mrs. Woodrow Wilson and was presented with a model of a Welsh harp with an American eagle at its base in solid gold. Kingston was very proud of his present and left it in his will to his son Bert. Kingston was engaged by the New York Metropolitan alongside Caruso performing most notably Manrico in Il Travatore–Campanini called him “the greatest Manrico of his day.” He had come a long way from singing “Nirvana” at the opening of the new drill hall in Mansfield. Now in his forties, Kingston worked harder than ever touring with the Scotti Opera Company as well as becoming a noted oratario and concert singer while performing in First World War fund-raising events. In 1924 he returned to England to appear at Covent Garden and undertaking concert work. He sang at a Stephenson subscription concert in Mansfield and his final performance was at the Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool in November 1928. Kingston’s health was failing and he finally moved to Stoke Poges–his family was now living in Canada. He died in a London Hospital on August 4 1936.

Chapter 20 of Ms. Bowers’s book finds her engaging Morgan Kingston on the subject of the spiritual side of the singer’s art.

Morgan Kingston:’ I want to have such control of myself that I shall be fitted to help and benefit every person in the audience who listens to me. Until I have thus prepared myself, I am not doing my whole duty to myself, to my art or to my neighbor.’

Introduction

“A man who has risen to his present eminence through determined effort and hard work, who has done it all in America, is a unique figure in the world of art. He can surely give much valuable information to students, for he has been through so much himself.” Thus I was informed by one who was in a position to understand how Morgan Kingston had achieved success. The well-known tenor was most kind in granting an audience to one seeking light on his ideas and experiences. He welcomed the visitor with simple, sincere courtesy, and discussed for an hour and a half various aspects of the singer’s art.

“In what way may I be of service to you?” began Mr. Kingston, after the first greetings had been exchanged.

“There are many questions to ask,” was the answer; “perhaps it were best to propound the most difficult one first, instead of reserving it till the last. What, in your opinion, goes into the acquiring of Vocal Mastery?”

“That is certainly a difficult subject to take up, for vocal mastery includes so many things. First and foremost it includes vocal technic. One must have an excellent technic before one can hope to sing even moderately well. The singer can do nothing without technic, though of course there are many people who try to sing without it. They, however, never get anywhere when hampered by such a lack of equipment. Technic furnishes the tools with which the singer creates his vocal art work; just as the painter’s brushes enable him to paint his picture.

Rules Of Technic

“I said the singer should have a finished technic in order to express the musical idea aright, in order to be an artist. But technic is never finished; it goes on developing and broadening as we ourselves grow and develop. We learn by degrees what to add on and what to take away, in our effort to perfect technic. Students, especially in America, are too apt to depend on rules merely. They think if they absolutely follow the rules, they must necessarily become singers; if they find that you deviate from rule they tell you of it, and hold you up to the letter of the law, rather than its meaning and spirit. I answer, rules should be guides, not tyrants. Rules are necessary in the beginning; later we get beyond them—or rather we work out their spirit and are not hide-bound by the letter.

Early Struggles

“As you may know, I was born in Nottinghamshire, England. I always sang, as a small boy, just for the love of it, never dreaming I would one day make it my profession. In those early days I sang in the little church where Lord Byron is buried. How many times I have walked over the slab that lies above his vault. When I was old enough I went to work in the mines, so you see I know what hardships the miners endure; I know what it means to be shut away from the sun for so many hours every day. And I would lighten their hardships in every way possible. I am sure, if it rested with me, to choose between having no coal unless I mined it myself, I would never dig a single particle. But this is aside from the subject in hand.

“I always sang for the love of singing, and I had the hope that some day I could do some good with the gift which the good God had bestowed on me. Then, one day, the opportunity came for me to sing in a concert in London. Up to that time I had never had a vocal lesson in my life; my singing was purely a natural product. On this occasion I sang, evidently with some little success, for it was decided that very night that I should become a singer. Means were provided for both lessons and living, and I now gave my whole time and attention toward fitting myself for my new calling. The lady who played my accompaniments at that concert became my teacher. And I can say, with gratitude to a kind Providence, that I have never had, nor wished to have any other. When I hear young singers in America saying they have been to Mr. S. to get his points, then they will go to Mr. W. to learn his point of view, I realize afresh that my experience has been quite different and indeed unique; I am devoutly thankful it has been so.

What The Teacher Should Do For The Student

“My teacher made a study of me, of my characteristics, mentality and temperament. That should be the business of every real teacher, since each individual has different characteristics from every other.

“It is now ten years since I began to study the art of singing. I came to America soon after the eventful night which changed my whole career; my teacher also came to this country. I had everything to learn; I could not even speak my own language; my speech was a dialect heard in that part of the country where I was brought up. I have had to cultivate and refine myself. I had to study other languages, Italian, French and German. I learned them all in America. So you see there is no need for an American to go out of his own country for vocal instruction or languages; all can be learned right here at home. I am a living proof of this. What I have done others can do.

The Technical Side

“As for technical material, I have never used a great quantity. Of course I do scales and vocalizes for a short time each day; such things are always kept up. Then I make daily use of about a dozen exercises by Rubini. Beyond these I make technical studies out of the pieces. But, after one has made a certain amount of progress on the technical side, one must work for one’s self—I mean one must work on one’s moral nature.

The Moral Side

‘I say it in all humility, but I am earnestly trying to conquer the errors in myself, so that I may be able to do some good with my voice.

“I believe strongly that a singer cannot adequately express the beautiful and pure in music while cherishing at the same time a bad heart and a mean nature behind it. Singing is such a personal thing, that one’s mentality, one’s inner nature, is bound to reveal itself. Each one of us has evil tendencies to grapple with, envy, jealousy, hatred, sensuality and all the rest of the evils we are apt to harbor. If we make no effort to control these natural tendencies, they will permanently injure us, as well as impair the voice, and vitiate the good we might do. I say it in all humility, but I am earnestly trying to conquer the errors in myself, so that I may be able to do some good with my voice. I have discovered people go to hear music when they want to be soothed and uplifted. If they desire to be amused and enjoy a good laugh, they go to light opera or vaudeville; if they want a soothing, quieting mental refreshment, they attend a concert, opera or oratorio. Therefore I want to give them, when I sing, what they are in need of, what they are longing for. I want to have such control of myself that I shall be fitted to help and benefit every person in the audience who listens to me. Until I have thus prepared myself, I am not doing my whole duty to myself, to my art or to my neighbor.

“We hear about the petty envy and jealousy in the profession, and it is true they seem to be very real at times. Picture two young women singing at a concert; one receives much attention and beautiful flowers, the other—none of these things. No doubt it is human nature, so-called, for the neglected one to feel horribly jealous of the favored one. Now this feeling ought to be conquered, for I believe, if it is not, it will prevent the singer making beautiful, correct tones, or from voicing the beauty and exaltation of the music. We know that evil thoughts react on the body and result in diseases, which prevent the singer from reaching a high point of excellence. We must think right thoughts for these are the worthwhile things of life. Singing teachers utterly fail to take the moral or metaphysical side into consideration in their teaching. They should do this and doubtless would, did they but realize what a large place right thinking occupies in the development of the singer.

“One could name various artists who only consider their own self-aggrandizement; one is compelled to realize that, with such low aims, the artist is bound to fall short of highest achievement. It is our right attitude towards the best in life and the future, that is of real value to us. How often people greet you with the words: ‘Well, how is the world treating you today?’ Does any one ever say to you—’How are you treating the world to-day?’ That is the real thing to consider.

“As I said a few moments ago, I have studied ten years on vocal technic and repertoire. I have not ventured to say so before, but I say it tonight—I can sing! Of course most of the operatic tenor rôles are in my repertoire. This season I am engaged for fourteen rôles at the Metropolitan. These must be ready to sing on demand, that is at a moment’s notice—or say two hours’ notice. That means some memory work as well as constant practice.

“Would I rather appear in opera, recital or oratorio? I like them all. A recital program must contain at least a dozen songs, which makes it as long as a leading operatic rôle.

“The ten years just passed, filled as they have been with close study and public work, I consider in the light of preparation. The following ten years I hope to devote to becoming more widely known in various countries. And then—“–a pleasant smile flitted over the fine, clean-cut features—”then another ten years to make my fortune. But I hasten to assure you the monetary side is quite secondary to the great desire I have to do some good with the talent which has been given me. I realize more and more each day, that to develop the spiritual nature will mean happiness and success in this and in a future existence, and this is worth all the effort and striving it costs.”

Vocal Mastery: Talks With Master Singers And Teachers

Vocal Mastery: Talks With Master Singers And Teachers

Comprising Interviews With Caruso, Farrar, Maurel, Lehmann, And Others

By Harriette Brower

(Author of Piano Mastery, First and Second Series, Home-Help in Music Study and Self-Help in Piano Study)

Published by Frederick A. Stokes Company Publishers 1917; by Oliver Ditson Company New York 1918, 1919; by The Musical Observer Company 1920.

Free e-book available at Project Gutenberg