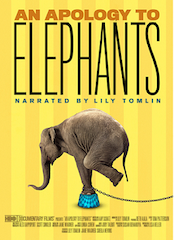

This undated publicity photo released by courtesy of HBO shows narrator Lily Tomlin in the documentary film, “An Apology to Elephants.” The film is an unabashed polemic, calling for improved treatment of elephants in zoos and an end to the use of the animals as entertainment, which the film contends must invariably involve abuse. (AP Photo/HBO, Lisa Jeffries/pawsweb.org)

Let’s take a moment to look at some of the awards Lily Tomlin has collected during a 50-year career.

And I hasten to emphasize we’ll only be looking at some of Tomlin’s awards—otherwise, there’d be no way to stick with the moment part; if we examined all of them, heck, the process could take hours.

Let’s see, she has seven Emmys.

Two Tonys.

Two Peabody Awards.

A Grammy.

The Mark Twain Prize for American Humor.

Not too shabby.

Of course, it makes perfect sense.

These prizes recognize that the comedian-actress with the smiley eyes has turned her colossal talents toward a sweeping array of projects spanning nearly five decades, ranging from her breakout stint on Laugh-In, which began in 1969, to the long-running ‘80s Broadway hit The Search For Signs Of Intelligent Life in the Universe, to last year’s film Admission, also starring Tina Fey and Paul Rudd.

Anyone with even passing familiarity with Lily Tomlin is probably conversant with at least the most acclaimed contours of her career. Still, even some of the most ardent aficionados may not realize she has a similarly distinguished record in the realm of animal welfare.

Trailer for the HBO documentary, An Apology to Elephants, featuring narration by Lily Tomlin

In fact, she’s won awards for that work, too, including the Petco Foundation’s Hope Award, which “celebrates the spirit of hope through a life dedicated to promoting the human-animal bond” and specifically recognizes her “dedicated work and commitment to animal welfare.”

Among the roles the Petco award reflects is that Tomlin is a longtime member of Actors and Others for Animals, the animal welfare organization founded in 1971 by the late actor Richard Basehart that Deep Roots readers may remember Fred Willard describing in our October 28, 2013 Talking Animals profile of Willard (“Best in Show: Fred Willard in Anything, Including Animal Welfare”), Tomlin currently sits on the organization’s Board of Directors.

Indeed, taking a closer look at the most recent of those seven Emmys betrays Tomlin’s devotion to animals: She won that Emmy for Narration on last year’s HBO documentary, An Apology To Elephants, which she also produced with wife and longtime collaborator Jane Wagner.

At the same time, for those paying close attention to her off-screen activities in recent years, the Tomlin-driven doc hardly arrived out of the blue.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k9e3dTOJi0o

Lily Tomlin as Ernestine the telephone operator in a classic Laugh-In moment

Some half dozen years ago, I started noticing stories popping up about Lily Tomlin speaking out in decidedly pro-pachyderm ways. She was urging the release of elephants from the Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle…making similar pleas on behalf of Jenny, an elephant at the Dallas Zoo…Packy from the Oregon Zoo…Rosie hanging out by herself in a facility in Maine (Maine!)

As a card-carrying elephant nut, I was really struck by this—not to mention, it provided even more reasons to adore Lily Tomlin.

In an April 2 interview on Talking Animals, I asked Tomlin how all these elephant efforts had come about.

“I think largely it happened when they were trying to free Billy and Ruby from the L.A. Zoo and get them to a sanctuary,” she answered, referring to a controversy that erupted about a decade ago, after the companion of Ruby the elephant died at the Los Angeles Zoo, leaving her isolated there.

This divisive situation later included a male elephant named Billy—elephant advocates sought to have them both relocated to a sprawling sanctuary in Northern California.

“A friend that I knew was very active in that protest. So I wrote a letter to [L.A.] Mayor Villaraigosa. But to write it, I had to read a lot about elephants. I mean, I had a certain consciousness, but I didn’t know very much about the facts about elephants in captivity.

“So as I read and became more and more interested. I guess the situation started to symbolize the elephant in the room, or the elephant on the planet.

“Because I thought it was just so patently obvious that these animals [shouldn’t be in zoos]—the AZA guidelines for elephants in captivity was space equal to a three-car garage!”

Baby Elephant Walk, written by Henry Mancini for the 1961 film Hatari! To Lily Tomlin, the sight of elephants in captivity, confined in artificial habitats conforming to AZA guidelines as being space equal to a three-car garage, ‘became so symbolic of the suffering in the world in general, at the hands of humans.’

Tomlin said a mouthful (trunkful?) there. Let’s back up a bit.

The AZA is the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, a trade organization that oversees zoos and aquariums, and sets the standards for how animals are displayed at those facilities.

Most who would identify themselves as animal advocates hold a dismissive view of The AZA (Tomlin, affecting a hoity-toity voice: “My god, it’s AZA approved! What more do you want?”), in no small measure because it unapologetically formulates regulations for exhibiting animals that places commerce above the critters’ welfare.

To wit, proscribing preposterously small dimensions for elephant exhibition areas (“equivalent to a three-car garage”), when, in the wild, these animals are highly social creatures who routinely roam 30 to 50 miles per day.

That’s a distance that probably exceeds the area of most three-car garages. Not coincidentally, perhaps, elephants are typically the major marquee attraction—crucial to ticket sales and attendance—at zoos.

“The campaign to move Ruby from the Zoo to PAWS was successful,” Tomlin recalled, picking up the thread of the story, noting that in the wake of Ruby’s relocation to the 2300-acre sanctuary operated by the Performing Animal Welfare Society (PAWS), she forged a friendship with PAWS co-founders Ed Stewart and the late Pat Derby.

Derby is one of the elephant experts featured in An Apology To Elephants. Others interviewed in this film that examines the psychological trauma, physical damage and general plight of captive elephants in zoos and circuses include Cynthia Moss and Joyce Poole, recognized as among the world’s top authorities on elephants.

With An Apology in mind, I couldn’t help wondering how Lily Tomlin catapulted from researching and writing that missive to the L.A. mayor about elephants, to narrating and co-producing an HBO documentary about them.

“It was just part of moving forward in that desire to bring awareness and consciousness to the issue,” she said. “I went to HBO and suggested they do a documentary on elephants, and that was the result of it.”

And that, ladies and gentlemen, represents the virtue—the powerhouse perk–of being Lily Tomlin.

You have an amazing showbiz track record, you’re enormously respected, you’re deeply beloved—you’re Lily Tomlin, for Chrissakes! You walk into HBO, explain why they should make a documentary about elephants…and they do!

“It doesn’t happen that easily,” she said. “It’s not like I could just do that at a whim. I just happened to hit the right moment.”

Sure, sure. But when I underscore that this extends well beyond “the right moment,” that it’s wholly about being Lily Tomlin, I describe what would likely happen if I walked into HBO’s office, had the same conversation, they’d likely say “Hey, how did you get past security?”

She laughs heartily (something she did often during our conversation; she was every bit as nice and generous of spirit as you would hope), then: “You’re right, people who have profile–of course, that’s one of the benefits.”

Acknowledging that some of the more outspoken facets of her elephant crusading have drawn some static and “less-than-kind letters,” her dedication to them remains resolute.

I ask her about the emotional underpinnings of that dedication: what does she see in elephants, what enchants her about them?

“The incredible, unique physicality of them in this time,” she answered. “There were creatures larger in the past, but I don’t know if there’s been any more magnificent.

“And reading about their grieving and their emotional life, and how sensitive and aware they seem to be. But I feel that about all animals.

“But it’s documented about elephants, and known and studied, and attested to by experts, elephant experts. The grieving is really profound.

“And the idea that they could crush anybody who’s abusing them. And the fact that they are stoic for so long.

“And, of course, they will break and do things, and attack and take revenge on abusers. Or people they identify as abusers. This is after years and years of labor and suffering.

“But it’s more symbolic, about being so large and so obvious in their needs for movement and space. It’d be like living in a closet yourself for 30, 40, 50 years. Elephants who are captive in a very small zoo space, with the earth compacted like it’s cement, their feet are very nimble and sensitive, really.

“They’re used to walking and ambulating and being on a soft surface—grass and dirt. Anyway, it’s so obvious to me, as I said, it became so symbolic of the suffering in the world in general, at the hands of humans.”

Follow this link to listen to the Talking Animals encounter with Lily Tomlin.