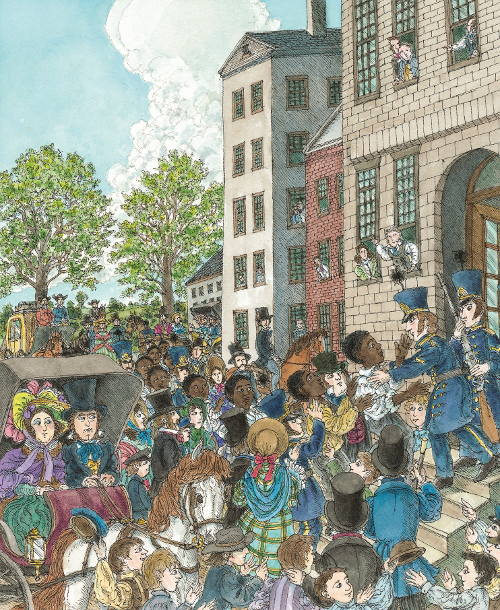

The crowds at the Hartford jail were even greater than those in New Haven. Evidently Africans like ourselves were a novelty, and so people streamed into the jail, often traveling long distances, to see what we looked like.”

(Click image to see spread in its entirety, including the text)

Last month at Kirkus, I wrote about some 2013 Picture Books That Got Away — that is, those books that during the year I had planned to write about here at 7-Imp or over at Kirkus, yet for one reason or another I didn’t get to them.

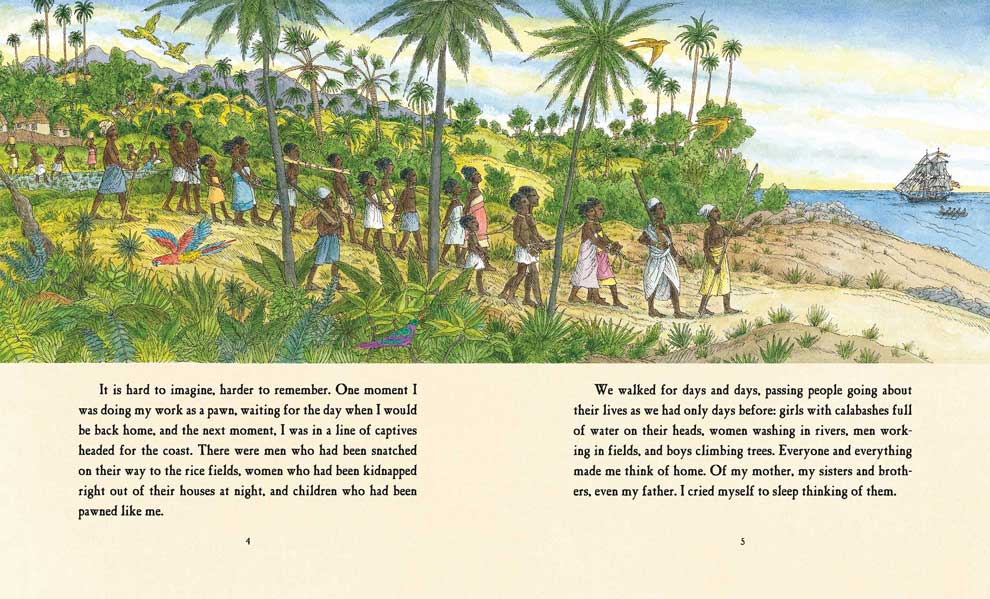

One book I wanted to include in that list, yet I knew I’d be writing about it today, is Monica Edinger’s Africa Is My Home: A Child of the Amistad (Candlewick, October 2013), illustrated by Robert Byrd. This is a lengthier picture book, geared (if you heed such labels) at slightly older readers. (“10 to 14 years old” is how the publisher thinks of it.) This is the fictionalized story of the real-life child named Margru, who later became known as Sarah Kinson, taken from her home by slave traders in Mendeland, West Africa, “one of the greenest places on earth,” in 1839. At the age of nine, Margru’s father decided she would go as a pawn to work for the family of a man in her village. This would occur in exchange for rice, given that the village in which Margru and her family lived was suffering greatly from drought and famine. “At the next harvest,” her father told her, “I will return what I owe and you will come home.” Margru did as she was told, only to find soon after that she was “in a line of captives headed for the coast.” Slave traders transported Margru and many other West Africans, including three other children, to Cuba and later to the U.S. on the Spanish slave ship called the Amistad.

The Africans aboard ship eventually revolted, yet not long after that became prisoners once again. Though they ended up as prisoners in a part of the States where slavery was considered illegal, the men aboard the ship were tried for murder in New Haven, Connecticut. Here, Margru lived, was educated, and was converted to Christianity. Later, in 1841, the Supreme Court declared that the Africans were freed. Margru returned to Africa to teach and assist in establishing a mission, only to return to America again at age sixteen, where she studied at Oberlin College—and in great despair. She missed Africa, writing to a friend, “I would not stay in this country for a thousand dollars were it not for the education.”

“It is hard to imagine, harder to remember. One moment I was doing my work as a pawn, waiting for the day when I would be back home, and the next moment, I was in a line of captives headed for the coast.” (Click image to see spread in its entirety)

Eventually, she returned home. Edinger closes the book on a cryptic and hopeful note, during which two men approach Margru—now grown, of course—and ask if she’d like to see her father. In her closing Author’s Note, Medinger explains how this final scene is something Margru had mentioned in a letter and that it’s not known for sure if she and her father ever met again. “In fact,” Medinger writes, “she and her husband left the mission not long after this and nothing further about her life is known.”

This is an emotionally compelling narrative, Edinger lacing it with poignant moments that depict Margru’s dreams: The child dreams of her mother, her father, her elders back home in Africa. Of the latter, she writes, “Telling us children stories of greedy Spider and clever Rabbit. Teaching us to be patient and brave always. … I dreamed of home.” In the hands of a lesser author, Margru’s story would have been a less-than-inspiring listing of facts, but Edinger makes it a gripping tale, heart-rending as it is in spots. It’s a well-paced narrative; Edinger lets the suspense and drama build, as readers wait to discover the fate of the children.

Byrd’s illustrations are detailed and equally dramatic. Archival documents, such as newspaper clippings, are included. (See above.) Most striking of all is the spread that describes Margru’s first journey across the ocean after first being stolen into slavery. The pages are pitch black—with white text detailing “seven weeks in a dark and airless hold.” It’s an arresting moment.

A captivating look at a captivating woman.

AFRICA IS MY HOME. Text copyright © 2013 by Monica Edinger. Illustrations copyright © 2013 by Robert Byrd. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.

This and many more of Jules’s adventures in books, kids’ lit and illustration can be found at her acclaimed blog, Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast, where the above interview was published on December 22, 2013.

This and many more of Jules’s adventures in books, kids’ lit and illustration can be found at her acclaimed blog, Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast, where the above interview was published on December 22, 2013.