by David McGee

Philip Chevron: ‘I think you can’t actually understand American music unless you acquire some understanding of Irish music’

Philip Chevron, who joined the Pogues as guitarist-songwriter-vocalist in the band’s second year and wrote the instant classic “Thousands Are Sailing,” an evocative, poignant ballad reflecting on Irish emigration to America, then became the driving force behind the Pogues’ comeback as a touring band in 2001, died on October 8 following a long battle with head and neck cancer. He had made his final public appearance at a Dublin concert held in his honor held this past August. He 56; his only survivors are his mother and sister.

Born to a father who was an actor and theater producer in Dublin, Chevron (neé Philip Ryan), was a true Renaissance man. Experienced and conversant in the arts and literature, he as comfortable in live theater (in fact in recent years he had accepted a number of commissions to write music for the theater, including from London’s prestigious Old Vice and Galway’s Druid Theatre) as he was on the concert stage and in the recording studio. A gifted writer, his online diary entries were one of the early Internet’s genuine pleasures as islands of civility, insight, humor and plain, unvarnished information about the Pogues’ latest activities. (These “diaries” are no longer available, as his website has been closed). He also was the resident historian, the fount of the most factual information, about Ireland’s pioneering punk band, The Radiators from Space, of which he was a founding member and the impetus behind their return to the studio a few years back. He joined the Pogues following the Radiators’ 1981 split, and became the band’s solid center onstage, maintaining his composure while his wild and woolly mates danced jigs, threw themselves on the floor and at each other, bemusedly surveying the surrounding madness while nattily attired in a well-tailored casual suit and Sinatra-style fedora tilted back on his head. (No statue he, though: Chevron could whirl about and jig with the best of them, but he picked his spots.) When his solo turn came around, he would step up and offer “Thousands Are Sailing,” and bring tears and a sense of calm to a sea of rowdy concertgoers.

The Radiators from Space, ‘Song of the Faithful Departed,’ written by Philip Chevron (guitar)

I knew Philip Chevron. Not to the point of calling him a close personal friend, but friend enough that he always contacted me on his regular visits to New York and was always generous with guest list privileges for me and my family when the Pogues came to town for their annual St. Patrick’s Day concerts–not a one-day event but usually a three- or four-day stand necessitated by an overwhelming demand for tickets.

We met on April 7, 2005. I know the exact date because it was the occasion of my interview with him for a biography of Steve Earle I was working on, and the subject was the session for “Johnny Come Lately,” one of the greatest of all Earle songs and one of the most powerful moments on his Copperhead Road album. In an earlier Earle biography, the recording of Copperhead Road in general, or of any particular song on it, was given short shrift, except for a mention that the colorful, brilliant and troubled lead singer-songwriter Shane MacGowan had arrived at the “Johnny Come Lately” session four hours late. That so monumental an album as Copperhead Road was almost an afterthought astonished me, and Philip in turn was disturbed by the factual inaccuracies in the brief account of Earle’s momentous summit with the Pogues. (An excerpt from the Copperhead Road chapter is reprinted below, including a Q&A with Chevron, who naturally places “Johnny Come Lately” and Steve Earle’s music in a broader historical context relating to the Irish strain in American roots music. Chevron even goes so far as to assert, “You can’t understand American music unless you acquire some understanding of Irish music.”)

The next year’s St. Patrick’s Day celebration brought the Pogues to the Nokia Theater in Times Square. One of the shows took place on March 17, 2006, which happened to be the same day my youngest son, Kieran (born in 1981 and named after Kieran Doherty, one of Irish republican hunger strikers, led by Bobby Sands, that died in Maze prison; while imprisoned, Doherty was elected to the lower house, i.e., Dáil Éireann, of the Irish parliament) was wed to his beloved Amanda. A week prior to this blessed event–both the marriage and the Pogues’ concert–I contacted Philip and asked if he could arrange for me to buy enough tickets for all of us to attend the show, as a wedding present to my son and new daughter-in-law. His answer: “You’re on the guest list. How many tickets do you want?” He arranged for our party of four to be seated in the VIP balcony above the stage, away from the surging, predictably inebriated crowd on the floor.

The Pogues, ‘Thousands Are Sailing,’ Nokia Theater, New York City, March 17, 2006. This clip was posted at YouTube by KimberDale and does not include Philip Chevron’s dedication of the song to a young couple that had been wed that morning, on St. Patrick’s Day.

When Philip’s solo spot came up, he stepped to the mic and said: “Some people party on St. Patrick’s Day and some people get married. Kieran McGee and his lovely wife got married today, and they’re here tonight. This is called ‘Thousands Are Sailing.’”

It seemed to me, standing there near tears over what I had heard from the stage, that when Philip arrived at a certain verse, he sang it with a little extra emotional conviction. I’m sure he knew at least two people in the room would hear it in a way they had not heard it before when he sang this verse:

In Manhattan’s desert twilight

In the death of afternoon

We stepped hand in hand on Broadway

Like the first man on the moon

A month later, a package arrived at my apartment with Philip’s name and address in the upper left corner. When I opened it, I found three DVDs, all containing the same four tunes from the March 17 show, including “Thousands Are Sailing” complete with Philip’s dedication–his wedding present to Kieran and Amanda.

This is the Irish bard I knew, a man with a heart as big as the Ireland he so loved who understood what was important in this life. How sad that Philip Chevron’s days were so short; how wonderful that such a man ever existed.

Sail on, my friend. Sail on.

The ‘Johnny Come Lately ‘ Session

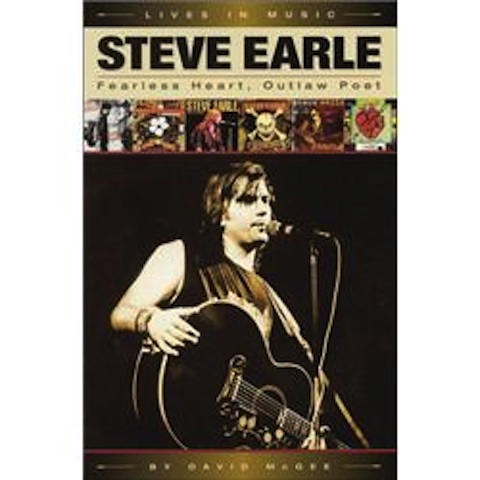

Excerpt from Steve Earle: Fearless Heart, Outlaw Poet

by David McGee

(Note: Apart from the Pogues and Steve Earle, the other important player in the following excerpt is Tony Brown, who had signed Steve to MCA Nashville and produced his first two acclaimed albums and was co-producer, with Steve, of Copperhead Road. An interview with Philip Chevron concludes this section.)

Steve Earle and The Pogues recording ‘Johnny Come Lately’ in London

“My granddaddy sang this song/Told me about London when The Blitz was on…”

On September 7, 1940, at approximately 4 p.m., 348 German bombers, with an escort of 617 fighter planes, began raining bombs on London in an effort by Nazi dictator/madman Adolf Hitler to force the British into surrender. Two hours after the first wave of bombers, a second wave struck and continued pounding the city until 4:30 the following morning. For 57 consecutive days London was bombed by the Germans, and the attacks were sustained through May of the following year. On May 11, 1941, Hitler called off what become known as The Bltz, and ordered his Luftwaffe air force eastward to prepare for Germany’s ill-fated invasion of Russia; the previous night, May 10, had been the deadliest night of all, with some 3,000 Londoners killed in bombing raids.

America’s respected WWII war correspondent Ernie Pyle described the initial attack as “a night when London was ringed and stabbed with fire,” and observed: “There was something inspiring just in the awful savagery of it.”

“There’s nobody here, maybe nobody knows/About a place called Vietnam”

On April 30, 1975, the war in Vietnam ended when the Saigon government announced its unconditional surrender to the Vietcong army of North Vietnam. In a final scene of desperation and chaos, the last of the U.S. military in Vietnam, trailed by U.S. Embassy employees, raced up to the roof of the Embassy roof, boarded waiting evacuation helicopters and were airlifted out to safety.

“I was crying and I think everyone else was crying. We were crying for a lot of different reasons,” said Major James Kean, one of the last evacuees from the Embassy roof. “But most of all we were ashamed. How did the United States of America get itself in a position where we had to tuck tail and run?”

Casualties in the Vietnam War: One million Vietnamese combatants, four million civilians killed; 55,926 Americans killed, 2,300 listed as Missing in Action.

There were no parades for returning Vietnam vets, only a legacy of shame that has still not completely worn off thirty years after the fall of Saigon. Filmmakers found no John Waynes to kick ass on the sands of Iwo Jimo; instead, the horror and insanity of Vietnam were embodied by pyschopathic, deeply scarred characters such as Tom Berringer’s monstrous Sgt. Barnes in Oliver Stone’s Patton, whereas the plight of the returning (and damaged) vets was vividly, searingly depicted in Stone’s Born On the Fourth of July and James L. Brooks’s Coming Home.

“We’re gonna drink Camden Town dry tonight…”

Located in the North London borough of Camden, Camden Town was founded in the 1790s by Charles Pratt, the Earl of Camden. The devastation caused by the Irish potato famine in the 1840s resulted in an influx of Irish immigrants into Camden Town, which was already in the process of being transformed from a bucolic, rural burgh into a bustling mini-metropolis as a result of ongoing canal construction and the building of a railroad link to the town. That process was completed in 1850 with the opening of the Camden Road railway station. Come World War II, the railway termini at Camden Town became an important target for German bombers.

“I’m an American, boys…”

The grandeur that is “Johnny Come Lately” begins with four simple, ringing chords strummed on a 12-string acoustic guitar, and Steve’s growling introduction, “I’m an American, boys…” The scene, as he later reveals, takes place in a Camden Town pub, and he’s singing in the voice of his grandfather (“my grandaddy sang this song…”), an American G.I. buying rounds for the townsfolk, gently criticizing the U.S.’s former isolationist policy (“it took a little while but we’re in this fight”) but assuring those assembled that the U.S. is staying “‘til we’ve done what’s right.” As he nears the end of the verse, his guitar is joined by a rolling swirl of notes from a lone banjo (played by the Pogues’ Jem Finer). When the second verse begins, the entire band kicks in, and the Irish dominate: the song gains the celebratory bravado of a rock ‘n’ roll Irish reel, an absolutely captivating burst of energy issues forth from the track, and when everyone comes in on the chorus—which describes a heavily medaled American G.I. returning home to waiting crowds at the train station in San Antonio—the force of the music mated to the lyrics is transcendent and triumphant, setting the stage for an instrumental passage of heartbreaking beauty fashioned out of a round of crisp, vibrant ensemble interplay, with Spyder Stacey’s haunting tin whistle floating majestically over it all, its airy flight and timeless melody evoking a sweep of Irish music ranging from the canon of the great 18th Century Irish harper Turlough O’Carolan to the melodies that made their way to America, to Appalachia and points south and southwest, providing solace for troops from the Alamo to Antietam. The second and third verses find the narrator meeting the love of his life in a field canteen, painting her name on the nose of his plane (“six more missions I’m gone”), and spending a long night with her during The Blitz, which inspires one of Steve’s most elegant lyrics, “death rainin’ out of the London night/We made love ‘til dawn,” a juxtaposition of terror and tenderness so succinctly and viscerally imagined it takes the breath away.

Granddaddy then extols his P47 as “a pretty good ship,” sings the praises of his “North End girl,” and vows to take her back to America with him “as soon as we win this war.” Another stomping instrumental break ensues, setting up the final verse, which cuts to the present day, with the narrator summarizing the story his granddaddy has told him, including “how he married Grandma and brought her back home.” From that sentiment we learn the narrator is in fact on that San Antonio runway he’s been singing about in the choruses, “couple Purple Hearts and I move a little slow,” but the hope of being greeted by waiting crowds of well wishers is dashed by the spectacle before him—no one is there. What next? Not the anticipated rage, but rather a curious kind of vocal shrug on Steve’s part, as if to say, “Huh. How ‘bout that?” Until he sings the lyric, “maybe nobody knows about a place called Vietnam,” and leans hard into the word “Vietnam,” almost spitting it out, his frustration finally boiling over into bitter sarcasm. The song closes out with several stanzas of the instrumental theme we’ve been hearing throughout, Spyder Stacey again and again taking flight on the tin whistle, which begins to sound like a haunted soul seeking safe haven, until, with the track fading, someone lets out a weary, resigned sigh, barely audible but nonetheless chilling as a coda.

Recorded at Livingstone Studios in London, with the great and volatile Irish punk band the Pogues in tow, “Johnny Come Lately” was testimony to the power of Steve’s vision of Copperhead Road. “He was bound and determined to make that happen,” says Tony Brown of the overseas session, “and he did.”

Steve had met the Pogues a couple of years earlier at the Abbey Road Studios in London, during sessions for the band’s epochal If I Should Fall From the Grace of God album. When he decided to try to line up the Pogues to accompany him on “Johnny Come Lately,” he had his management contact the band’s management with his request. His audacity in suggesting such a collaboration impressed the slightly mad musicians, according to Pogues’ guitarist Philip Chevron. Because to come into the Pogues’ world was to invite humiliation if you didn’t have your act wrapped tight.

“The approach came to us from his office, saying he had written this song that he thought was his response to a Pogues song from an American perspective,” says Chevron. “We knew straight away that for anyone to make that kind of a jump–and he’d already done it–it must be good; otherwise it would be really stupid to make the jump and be embarrassed by the song. So we actually said yes to it on spec, without even hearing ‘Johnny Come Lately,’ because we knew that to have the confidence to say ‘I’ve got a song here I think the Pogues can do,’ the guy’s gotta be good, he’s gotta know what he’s doing.’ And it was, it’s a great song, and it’s very clever from the point of view of how you interpret what the Pogues were doing as a sort of London Irish circle of the damned. Some lived in London, some still lived in Ireland, some had never been Irish, but they all converged on this sort of London Irish milieu in Camden Town. I think Steve got that pretty much straight away—Camden Town is mentioned in the song as a place where his grandfather goes to raise Cain. So it struck us as being an honorary Pogues song.”

At the studio Steve dealt with engineer Chris Birkett on the particulars of setting up for the session, while ordering Tony to make sure ten cases of Guinness Dark beer were in the studio for the Pogues’ consumption.

“I was in charge of making sure the Pogues had plenty of beer because they wouldn’t come to the studio unless they had lots of beer,” is how Brown remembers it.

Otherwise, the session for “Johnny Come Lately” was an undertaking of about a week’s time, only one day of it actually spent in the recording studio, many nights of it spent on stage making music, and, in the case of Steve and the Pogues’ Spyder Stacey, out on the town and roaring drunk. It was an incredible odyssey, by all accounts, that produced an astounding performance in the studio once the red light came on.

‘Johnny Come Lately,’ Steve Earle and the Pogues, from Copperhead Road

A CONVERSATION WITH PHILIP CHEVRON

‘…anyone who walked into our lives in those days, they joined the band’

At the time you heard about the session for “Johnny Come Lately” were you familiar with Steve’s music?

To some extent I was familiar. And I kind of knew by reputation that he was this rock guy who did country music, or this country guy who did rock music. So I was aware of him. And also, I have a huge soft spot for Texas music in general. I’m a major Doug Sahm fan. To me Doug is better than Elvis, because he was the greatest composite of Americana, blues and soul. Most of the people I admire most in American music are Texans, so I would have been aware of Steve’s work, but not as much as I would have liked to have been at the time.

It’s an amazing song. It wraps up 30-plus years of American history in three and a half minutes.

In some ways it also resonated for me as something of the Second World War and the American presence in England, where—what was the phrase they used?—“overpaid, oversexed and over here”–but obviously the American G.I. presence in England was usually welcomed. They brightened up the place and raised merry hell and it was great. With all the British men away at the war, American servicemen had quite a good time as well with the English ladies. So it somehow involved that, even though that wasn’t what it was about. But it sort of spoke of an earlier generation, and as a songwriter I identified very much with his writing strategies of using the freedom of the pop song structure to switch between the past and the present, sometimes blurring the distinctions as the song progresses.

What form was it in when you first heard it?

I was trying to remember that. I really don’t know. To be honest with you, things were moving really quickly at that point. In the context of recording “Johnny Come Lately,” it was like the maddest year of our lives. The previous December we had the hit single “Fairy Tale of New York,” Top 3 in Britain, and it made such an impression in England that when our album came out in January of ’88, it went straight into the Top 3 and suddenly we were big stars in Britain. We had gone from being this cult band to being a serious contender. We booked a show at Town & Country in Kentish Town on St. Patrick’s Day and tickets went so fast we kept adding more shows and playing St. Patrick’s week. This became partly a celebration of St. Patrick’s week, partly a celebration of what the Pogues represented in London—not just the Pogues but here for once was a positive Irish presence in a country where Irish racism had been rampant for three decades. It was unusual for people to stand up and say, “I’m Irish!” So those gigs at Town & Country were pregnant with meaning and consequence for all of us, and for the audience. And the Pogues responded in the only way they know how in moments of great consequence, and that’s to party their way through. At the same time we were aware that this was the most extraordinary week—also, two film crews came in to film all of this. “Hey, the Pogues are doing a week in London. We should make a film of it!” So we had one crew making a film of the show, another one making a documentary of the Pogues, which includes footage of the “Johnny Come Lately” session.

In addition to that I was guesting on an album called For the Children, a project to raise money for children for a non-sectarian effort for Northern Irish children. I was involved in that and so was Shane [MacGowan] and so was Terry Woods. And in the midst of all this, Steve was going, “When are we going to do this recording?”

We told him, “Believe it or not, the only time we can do it is that week, because that’s the only time we’re in London long enough to sort of focus on it.” So we had this mad situation where we were sound checking in the afternoons, going to the studio, doing the gig, going to a party and staying up all night, going back to the sound check, back to the studio, and all the events are kind of jumbled up that week. Meanwhile, a film crew were taking me off to Camden Town to a record shop I used to work in to show me in my old environment showing people Beach Boys records and stuff. And Shane was taken off somewhere else to show how he was writing his novel and got the call to be in the Pogues. Everyone had these little scenarios where the producer or director had decided he wanted to get to know us. So all this madness was going on as well.

Somehow into all this Steve Earle walked—anyone who walked into our lives in those days, they joined the band. It’s a simple as that. It wasn’t sufficient that you just hung around and waited for your bit; I think we learned “Johnny Come Lately” at the sound check the first day and Steve came on that night with us and did we performed it for the next two or three days. Mary Coughlin was also involved in those shows; Kirstie MacColl was involved; Joe Strummer; couple of people in a band put together by a guy who used to be in the Specials. It was Mad Dogs & Englishmen, like a Joe Cocker Revue or something. But it was organic and natural and still in keeping with the Pogues wanting to celebrate their moment of great triumph by bringing their friends along. Somehow it just seemed okay to do that. So Joe Strummer came on and did a couple of numbers, including “I Fought the Law.” Kirsty sang “Fairy Tale of New York” and “Dirty Old Town,” I think. Steve came on and did “Johnny Come Lately”—the Pogues Revue. And it was wonderful. What are these people gonna do? Sit backstage drinking? Get ‘em workin’! Get ‘em out there on stage!

Steve tells this story about how we got so accustomed to him coming out and doing “Johnny Come Lately,” and every night Terry Woods introduced him, (raspy, high-pitched voice), “And now, from the great State of Texas, to perform a song we just recorded called ‘Johnny Come Lately,’ ladies and gentlemen, Steve Earle!” and then one night nobody walks on. At this point Steve’s on his way back to the States and no one’s told Terry. He and his producer Tony Brown had pissed off that day, seriously hung over, three nights of partying with the Pogues, and we didn’t know Steve was gone.

But anyway we kept the song in the show—Spyder sang it for months, years after that. It was in the show for a long time; it was Spyder’s kind of spotlight number. And it proved that it’s a Pogues song in a funny sort of way because it blended with everything else.

The only reason I remember any of it is because of the documentary—it was captured on film.

What was the scene like in the studio when you got down to brass tacks?

It was funny because we took the view that Steve did, let’s get it nailed down right. Let’s get a feel going. Essentially it was the band playing live, including Shane, who was experimenting with rhythm banjo at the time. I was the guitarist. Steve was playing acoustic guitar, Jem Finer plays banjo, James Fearnley, accordion, Terry Woods played cittern, and Shane McGown played this kind of rhythm banjo. Shane was determined not to be left out of it.

One account of the session claims Shane showed up four hours late.

That’s entirely out of context. Shane showed up whenever it was time for him to be there. The drummer turns up first and gets the sound on his drum. The bass player turns up—these people have to be there. I assure you everyone was there when it came time to press the button and record. Neil MacColl, who plays mandolin, is Kirsty’s half brother. I didn’t know who Neil MacColl was, just somebody who was backstage and had joined the band that day, y’know.

Steve made a couple of adjustments to the arrangement as we went along, he did a guide vocal as we were putting it down. I’m not sure, he may even have used some of the guide vocal in the final mix. But I know that everything got down very quickly, with a minimum of messing around.

That’s Tony Brown’s recollection, too, that once you got down to it, it happened fast.

I think so. Anything that needed to be touched up or patched up, he did it right there.

Did you have much interaction with Tony?

I know more about Tony since then than I did then. I’ve since realized he’s a major, major producer, one of the top three or something. But like all the best producers, his job was not to impress himself but to translate the atmosphere onto tape; to capture bits that were good about it and make sure we didn’t lose any of that. I have to say he did a great job, but he wasn’t somebody who was garrulous and voluble. He was doing the job. I could tell also he was noticing when something was slightly out of the ordinary that would work—like Shane on the banjo and Tony going, “How can I make that work?” And actually getting on with doing it, where other producers would say, “Look, Shane, maybe we can think about the banjo later, maybe we can overdub it,” hoping to get him to go away. But Tony, to give him his due, was responsible to people and that’s where a good producer needs to be to get the best Pogues. With our eccentricity, self-absorption, whatever, you have to be able to see and pick up on what we’re doing. That takes intuition. So he probably was working very hard but not looking like it. Tony was like a swan, paddling underneath but calm above the water.

When Tony talked about this part of the album, he tried to get me to believe his only job was to bring in ten cases of Guinness to get the Pogues through the session.

The results speak for themselves. I think he did a real good job on that. It’s easy to say, “Oh, I just supplied the beer,” but it’s the hardest band in the world to produce and that’s why so few people did it. Really, Elvis Costello lasted for an album and a half and that was enough for him. Steve Lillywhite had enough of us and refused to do the third album—the second was too painful for him. So literally, in that case, always the perpetual Plan B—call up Joe Strummer, he’ll do it. I missed a tour in ’87 because I was in the hospital, and Joe was literally called two days beforehand and told he was going on tour with the Pogues. “Oh, okay, I’m not doing anything else this week, so fine.” They had to sit there and teach Joe the show, four hours. And equally, when we couldn’t get anyone to produce us for anything, the last days before we booked into the studio and still couldn’t find a producer willing to take a risk, Joe was called and told, “We’ve got a job for you, Joe. You’re going to produce our new album.” And when Shane left, Joe was the obvious choice for lead singer. He was never able to refuse us. Which was kind of good and kind of painful for him at the same time. Had he thought about it for longer than ten minutes, he might have said, “Uh-uh.” So I know how hard it is to produce the Pogues, and also I’ve been there—before I joined the band I produced a few tracks.

How was Steve during the actual sessions?

To me he seemed perfectly normal, so I don’t know. I was aware that he and Spyder were spending nights staying up, but that was a bit much for me. I have my limits. But I was aware that he and Spyder had forged this brethrenship of staying up all night. But I certainly wasn’t part of it. But nothing Steve did was getting in the way of the work in the studio.

That was the first time on record—of course it was only his third album—when he addressed the Irish connection at the roots of his music. He’s since referenced the Irish roots of his music on almost every album.

It’s definitely there, and it’s something I’m very interested in, it’s something Terry Woods is very interested in. Terry Woods learned Irish music through Appalachian music. Wasn’t hearing the great Irish fiddle players or pipers; that wasn’t the music he was seeking out. American folk music, and it was that that drove him back to Ireland. And also Woody Guthrie and so on. I’m very much aware of that in my own musical journey. It’s partly about how Irish music moved around the world and back. In some ways, the Texas connection, that story hasn’t been completely told. I was actually down in San Antonio a couple of weeks ago myself, talking to Sean Sahm, Doug’s son. He never heard of the Pogues, which is brilliant, because I was able to explain the Pogues, that essentially it’s like Irish music given a punk rock kick up the ass. The connection is there. David Crockett played fiddle at the Alamo. The late influx at the Alamo, a lot of those boys were Irish. Also at San Jacinto, where the Alamo damage was redressed, the marching tune there was “Will You Come to the Burgh,” which is based on an Irish tune and has become part of the standard American folk repertoire and was brought to America by the Irish. In the Texas-Mexico wars, there were Irish on both sides. That’s because there were Catholics who felt exiled from America by the Protestant majority and had gone to the Mexican side because they were Catholics. Most of the Alamo people were adventurers, pirates, slave traders, basically people who had run out of luck and had to move on further forward. To me there’s a lot of those loose ends that have not been tied up and it’s the one area Doug Sahm didn’t actually quite explore. And it’s interesting to me that Steve is exploring it as a Texan. It’s interesting to me how he’s been making that connection from the other side.

I think you can’t actually understand American music unless you acquire some understanding of Irish music. Inevitably, Irish music has tended to be more the foundation of American music. I grew up in Ireland with a huge distate for Irish music. Because it was part of official Ireland, it was in the same league for me as Gaelic Games and the Irish language and the Catholic Church—they were all part of the official Ireland that they tried to propogate as this new society, but a very sort of rural society and a very reactionary society in many ways. They felt they needed to embrace Irish culture in all its forms in opposition to British culture. You can’t do that. The Irish country has an imperial culture and having embraced that culture through people like Oscar Wilde, Winston Sheridan, George Bernard Shaw, the Anglo-Irish art form is very much a cornerstone.

Even the Chieftains were beyond the pale for me to listen to. They looked like schoolchildren, like they were part of the official doctrine of Irish thinking. The breakthrough didn’t happen for me until the early ‘70s when a band called Horslips came along. They had long hair and looked like they might smoke the occasional joint. They were obviously a rock ‘n’ roll band. But Horslips was a freak of nature. They didn’t mean to be a band; they got together for a commercial and they needed some guys who looked like a band. And they had such fun they thought, Wouldn’t it be a good laugh if we actually did become a band? Then they discovered that one used to play guitar, one played drums. When they got good at it they hadn’t been able to articulate and say, “What we’re doing here is illustrating that rock ‘n’ roll is based on Irish music.” Young people reclaimed Irish music through Horslips, reclaimed it through long hair and spangly suits and platform shoes, and they looked like they might smoke the occasional joint. Horslips opened the door to Sion O’Riordan, the Dubliners. So all of this is relatively new. Steve Earle came in at an interesting point, only a decade or so later, and it was still wide open, discovery and re-discovery.

In February 2005, I took the Amtrak train from Chicago to San Antonio, a service which takes around 36 hours. Arriving at San Antonio station behind schedule at 2 a.m. or so, and although I was not anticipating a welcoming committee (“they’ll be waiting at the station down in San Antone/When Johnny comes marching home”), I was struck by how romantic the scene still was, the gleaming silver train proud against the sky. And I became painfully aware that I was already watching a scene from America’s past–with the rapid demise of passenger trains in the USA (and at a time when they are environmentally friendly too), Steve Earle’s lyric is already nostalgic. The capacity to contain the future past in a contemporary lyric that already plays with time, is quite remarkable.

***

As the lyrics suggest, “Johnny Come Lately” is a song rooted in family history and lore. The main character, Granddaddy, is modeled after Jack Earle—not Steve’s father, but Steve’s father’s nephew, who served in the 8th Air Force in World War II, his entire tour of duty spent in England. While there he met and fell in love with a beautiful Welch girl, Mair Thomas. As soon as the war was won, Jack Earle (bearing the same name as Steve Earle’s father) married Mair Thomas (bearing the same maiden name as Steve Earle’s mother) and brought her home to America.”

“You know, we talked a lot and Steve would be there when we talked,” says Jack Earle, Steve’s father. “And she’s such a great person and loves to talk, so she was sort of one of Steve’s favorites, and that was just one of the stories of the Earles as we progressed along.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DrBLqp-s__o

The Pogues, ‘If I Should Fall from Grace with God,’ Philip Chevron on guitar

Philip Chevron: June 17, 1957-October 8, 2013

Phil Chevron, who has died aged 56, was one of Ireland’s best-loved and most influential punk rockers, and wrote The Pogues’ anthemic and enduringly popular ballad “Thousands Are Sailing.”

Originally featured on the 1988 Pogues album If I Should Fall From Grace With God, the song’s heartfelt lyric, soaring tune and compelling chorus on the theme of emigration from Ireland to America struck such a potent chord of authenticity with Irish audiences that it has already passed into folklore. Featuring regularly in informal Irish pub sessions, it is often performed by singers who often wrongly assume the song is traditional. It even served as inspiration for the 2012 Derek McCulloch graphic novel Gone To Amerikay.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gc1G7aCpSsI

The Pogues’ studio version of Philip Chevron’s ‘Thousands are Sailing’ with Shane MacGowan on lead vocal

The son of a Dublin actor and theatre producer, Philip Chevron was born Philip Ryan on June 17 1957. He changed his name in homage to the American record label Chevron, which released records by singers such as Judy Garland and Sarah Vaughan. In his teens, Phil also became a fan of the Irish-based Jewish actress, singer and political activist Agnes Bernelle, whose family had fled Germany shortly before the Second World War. The two later become firm friends, and he went on to produce her album Bernelle On Brecht And…

It was the punk music revolution, however, that consumed Phil Chevron in the mid-1970s and, with Steve Rapid and Pete Holidai, he formed Ireland’s first punk band, The Radiators From Space. Loud, aggressive, passionate, angry and energetic, they wrote short, sharp diatribes relating the hardships of working-class Dubliners at the time, and moved to London after their debut album, TV Tube Heart, was released in 1977.

They gained a measure of commercial success when David Bowie’s producer Tony Visconti collaborated with them on their ambitious second album, Ghostown (1979)–now considered one of the best and most influential Irish records of the era. Voted the third greatest Irish album of all time in an Irish Times poll in 2008, it included one of Chevron’s best songs, the enigmatic “Faithful Departed.”

The Radiators from Space at the Philip Chevron Testimonial Concert at Olympia Theatre, Dublin, August 24, 2013

After the Radiators split in 1981, Chevron remained in London and, working at a record shop near Tottenham Court Rd, met fellow Irishman Shane MacGowan, then in the early stages of his career fronting the band Poguemahone, who went on to become The Pogues. When the group’s banjo player Jem Finer was temporarily absent, MacGowan invited Chevron to sit in with them on guitar. By the time they came to record their classic second album, If I Should Fall From Grace With God, he had become a permanent addition.

While MacGowan remained the undisputed Pogues leader and frontman, the more restrained Chevron was a rock-strong accomplice, comfortably taking on occasional lead vocals, turning his hand to banjo and mandolin as well as guitar when the occasion demanded, and pitching in with more overtly tuneful material like “Thousands Are Sailing” and “Lorelei.”

The Pogues and The Dubliners on Top of the Pops (1987), ‘The Irish Rover’

Chevron initially remained a Pogue when the band sacked MacGowan and replaced him with Joe Strummer, but, battling drug and alcohol problems, he left in 1994. He later re-formed the Radiators with ex-Pogues bassist Cait O’Riordan, and enjoyed further success with them in 2006 with the album Trouble Pilgrim. He also became a key instigator in the renewed interest in The Pogues through the 2000s, personally remastering the band’s entire back catalogue on CD and taking a prominent role in their annual reunion tours.

In 2007 he was diagnosed with esophageal cancer. His last appearance was at a testimonial concert in his honour in Dublin in the summer.

From The Telegraph, October 9, 2013