Joseph Severn’s painting of Keats ‘Listening to the Nightingale on Hampstead Heath’, c. 1845. (Picture: Keats House Hampstead)

The love affair between poet John Keats and Fanny Brawne was doomed when they met in November or December of 1818. While nursing his brother Tom through a losing battle with tuberculosis (at that time an almost always fatal affliction, with doses of mercury being the preferred but highly ineffective treatment), John had exposed himself to infection; from that point forward he reveals in his letters, to Fanny and other friends in his circle, a sense of doom shadowing his every move. He feared he would be forgotten as a poet (his epic “Endymion” was savaged by critics, so much so that his friend and fellow poet Lord Byron claimed Keats’s life had been “snuffed out by an article”) and indeed, fame and critical respect came only years after his brief life flamed out at age 25, extinguished by the same disease that had claimed the lives of both Tom and his mother, Frances. Circa 1818, following a short but impassioned fling with Isabella Jones–which scholars believe to have been his sexual initiation–Keats was introduced to Frances (Fanny) Brawne, whose family was living opposite the Keats family in another part of Wentworth Place, a house owned by John’s friend Charles Armitage Brown. As Keats makes plain in the letter below, he was smitten from the start (“the very first week I knew you, I wrote myself your vassal”), and his love for Frances would only grow, in both intensity, jealousy and, finally, despair over their ever having a life together, in part because of his commitment to poetry as a calling, but more to what he had taken to calling the “family illness.” In the end, what we know of the Keats-Brawne love affair are the particulars and the emotions so boldly expressed in his surviving letters to her; on his deathbed in Rome, where he was attended by his friend and fellow artist Joseph Severn (who drew the portrait of Keats reproduced above), he directed that her letters to him be destroyed. We can only imagine what passions she might have admitted in her missives to John, but we can feel the fire that burned within him for her because he omitted no opportunity to articulate, oftimes in the most heated prose, every fear and exultation he felt in the throes of all consuming love. There are love letters and there are love letters, but the correspondence from John Keats to Fanny Brawne brooks few comparisons with respect to passion and poetry meeting on the page.

This letter is reproduced with the spellings and punctuation retained from Keats’s original. Read on below the postscript for Keats’s classic poem appropriate to the recent change of season, “To Autumn.”

25 July 1819

Shanklin

Sunday Night

My sweet Girl

I hope you did not blame me much for not obeying your request of a Letter on Saturday; we have had four in our small room playing at cards night and morning leaving me no undisturb’d opportunity to write. Now Rice and Martin are gone, I am at liberty. Brown to my sorrow confirms the account you give of your ill health. You cannot conceive how I ache to be with you: how I would die for one hour—for what is in the world? I say you cannot conceive it: it is impossible you should look with such eyes upon me as I have upon you: it cannot be. Forgive me if I wander a little this evening, for I have been all day employ’d in a very abstract Poem and I am in deep love with you—two things which must excuse me. I have, believe me, not been an age in letting you take possession of me; the very first week I knew you I wrote myself your vassal; but burnt the Letter as the very next time I saw you I thought you manifested some dislike to me. If you should ever feel for Man at the first sight what I did for you, I am lost. Yet I should not quarrel with you, but hate myself if such a thing were to happen—only I should burst if the thing were not as fine as a Man as you are as a Woman. Perhaps I am too vehement, then fancy me on my knees, especially when I mention a part of your Letter which hurt me; you say speaking of Mr. Severn ‘but you must be satisfied in knowing that I admired you much more than your friend.’ My dear love, I cannot believe there ever was or ever could be any thing to admire in me especially as far as sight goes—I cannot be admired, I am not a thing to be admired. You are, I love you; all I can bring you is a swooning admiration of your Beauty. I hold that place among Men which snubnos’d brunettes meeting eyebrows do among women—they are trash to me—unless I should find one among them with a fire in her heart like the one that burns in mine. You absorb me in spite of myself—you alone: for I look not forward with any pleasure to what is call’d being settled in the world; I tremble at domestic cares—yet for you I would meet them, though if it would leave you the happier I would rather die than do so. I have two luxuries to brood over in my walks, your Loveliness and the hour of my death. O that I could have possession of them both in the same minute. I hate the world: it batters too much the wings of my self-will, and would I could take a sweet poison from your lips to send me out of it. From no others would I take it. I am indeed astonish’d to find myself so careless of all charms but yours—remembering as I do the time when even a bit of ribband was a matter of interest with me. What softer words can I find for you after this—what it is I will not read. Nor will I say more here, but in a Postscript answer any thing else you may have mentioned in your Letter in so many words—for I am distracted with a thousand thoughts. I will imagine you Venus to night and pray, pray, pray to your star like a Hethen.

Yours ever, fair Star,

John Keats

My seal is mark’d like a family table cloth with my mother’s initial F for Fanny: put between my Father’s initials. You will soon hear from me again. My respectful Compts to your Mother. Tell Margaret I’ll send her a reef of best rocks and tell Sam I will give him my light bay hunter if he will tie the Bishop band and foot and pack him in a hamper and send him down for me to bathe him for his health with a Necklace of good snubby stones about his Neck.

TO AUTUMN.

John Keats (1795-1821)

1.

SEASON of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss’d cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For Summer has o’er-brimm’d their clammy cells.

2.

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap’d furrow sound asleep,

Drows’d with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cyder-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours.

3.

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,—

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

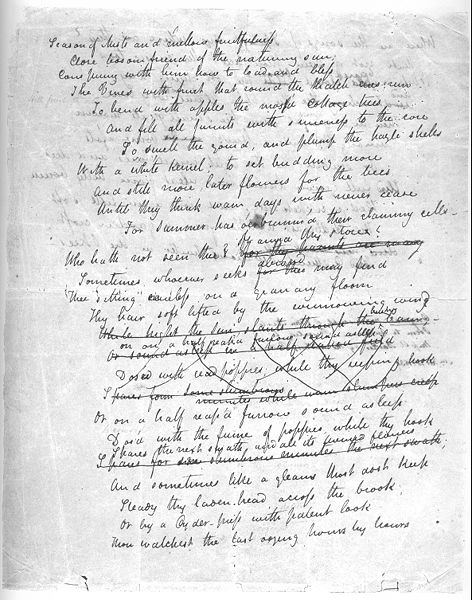

The first page of John Keats’s manuscript of his poem ‘To Autumn,’ 1819

‘To Autumn,’ by John Keats, read by Janet Harris

Music: Shostakovich, Fugue no. 1 in C major. Moderato (4-voice). Piano: Alexander Melnikov from the album Shostakovich: 24 Preludes & Fugues.