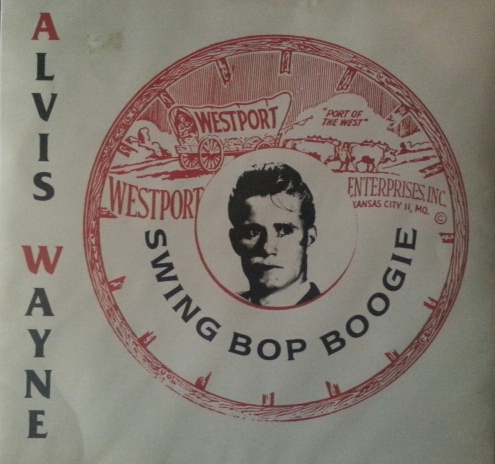

Alvis Wayne Samford, aka Alvis Wayne, in a late ‘50s publicity still: ‘If I could go back and change anything I would never have got married the first time and I wouldn’t have had to worry about all that family stuff I gave up my music for and I just might have made it. But I just couldn’t keep myself from falling in love.’

Alvis Wayne Samford, professionally known as Alvis Wayne, in which guise he was a highly regarded, albeit obscure, rockabilly pioneer, whose wild 1956 single “Swing Bop Boogie” knocked Elvis Presley from the top spot of the local charts in the Corpus Christi, TX, area, passed away on July 31 at his home in Bacliff, TX. He was 75. Although his recording output during rockabilly’s heyday in the late ‘50s was scant—five singles for the Kansas City-based Westport label that made hardly a ripple outside Wayne’s home turf in and around the Lone Star State’s Gulf Coast—and he was never able to make a full-time living as a musician, he experienced a late-life career resurgence when Rockin’ Ronnie Weiser, founder of Rollin’ Rock Records, tracked him down in Texas. Weiser then produced and released two acclaimed Alvis Wayne albums, 2000’s Rockabilly Daddy and 2001’s I’m So Proud of My Rockabilly Roots, that brought the artist some measure of recognition denied him in his younger years.

Born in Paducah, Texas on December 31st 1937 to Alva N. and Nona Mae Samford, Alvis was the eldest of five children. He had a sister, Barbara, and three brothers, Norvin, Robert and J.W.

The Samfords, who were extremely poor, left Paducah shortly after Alvis was born. One of 14 children, Alvis’s father was a carpenter by trade, but he had to go anywhere where there was work, which during the depression of the ‘30s was very scarce indeed. He worked in a machine shop, picked cotton, chopped cedar, worked on a dairy farm, anything at all that would enable him to support his growing family. Alvis’s mother stayed home raising the family, although she occasionally worked as a waitress to put a few extra dollars into the family kitty. His father’s constant quest for work meant the family moved frequently, putting down stakes in Martin Springs, West Texas, and several little towns around San Antonio until finally settling down in Corpus Christi in early 1953, where Alvis attended Sundeen High School.

“My early childhood was just like anybody else’s of that time period,” Alvis said in an interview. “I fought a lot with my brothers and my sister—well, she could whip all of us–but I don’t think my life was any different to any other child’s life at that time. We kids slept in a small bunkhouse behind the main house and I had a small radio that I would listen to until the early hours of the morning. Jimmie Rodgers, the Mississippi Blue Yodeler, Hank Snow, Eddy Arnold and Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys were early influences. I was twelve years old when I heard my first live radio show from KBOP in Pleasanton, Texas. I also listened to a station out of Del Rio, Texas, as well as an R & B station in Shreveport, Louisiana. On Saturday nights we listened to WSM and the Grand Ole Opry.”

When he was 10 he gathered corn all summer on his aunt and uncle’s farm to earn enough money for his first guitar, which his aunt ordered from a Sears & Roebuck catalogue for a pricey $18.98 plus shipping and handling. He taught himself by studying a “How to Play Guitar” book and first learned Lead Belly’s “Goodnight Irene.”

Alvis Wayne, a latter day performance of his 1956 single, ‘Sleep Rock-A-Roll Rock-A-Baby’

However, Alvis’s ambition of becoming a performer didn’t sit well with his devout family. “I became the black sheep. My grandparents were very religious and in the church that I was raised in believed that Saturday was the Sabbath and they believed the Sabbath started at 6 o’clock on Friday afternoon, so you couldn’t go to the movies or play in honky tonks. They didn’t believe in any of that kinda stuff and it was strictly against the religion. When I got up to be twelve and thirteen years old I started playing in the nightclubs and all that stuff. Friday was the busiest night of the week so there was a whole bunch of them who didn’t take to kindly to it all. At that same time one of my aunts, who was supposed to be part of this thing, encouraged me along and that’s the same aunt who bought me that guitar. Most of the big stars came to San Antonio; it was one of the swingin’est towns in the state. I guess when I was about ten years old. I got on the bandstand with Bob Wills in a little old town called Macdona, about thirty miles out of San Antonio. They all came, George Jones, Ray Price you name it and if they were in the business, they played in San Antonio.”

Although he was a good student, the academic life at Sundeen High wasn’t for Alvis. Eventually he dropped out and begain performing locally in honky tonks and nightclubs for little more than beer money. “My mom and dad were not very happy about me going out on the road, but I had an opportunity to do so with a band, which was the only thing I ever wanted to do. As I said they weren’t very happy about it at all and we talked about it for several days, but I just had to go. They eventually went along with it all and didn’t hold me back.

Alvis Wayne, a live performance of his long-unissued Westport recording ‘I Gottum’

One night he was approached by a local musician, Anthony (Tony) Wayne Guion, leader of a band called the Rhythm Wranglers, a quartet comprised of bass, drums, rhythm and lead guitars, with Tony on rhythm and lead vocals. In 1957 this group cut its first and only release on Westport Records called “Many Ways”/”Together Forever” (Westport 134). Life on the road was tough and disillusioning. The band earned so little it had to do without food on some days, until finally the musicians parted ways.

Alvis then joined another local band, AI Hardy and the Southernaires, and once again started doing gigs virtually seven nights a week. In fact AI Hardy not only had one of the finest country and western swing bands in the state but he also owned a Corpus Christi nightclub. Meanwhile, Tony Wayne Guion remained in regular contact. During the summer of 1956 he approached Alvis with a view to doing some recording.

“Tony came up to me and said ‘Hey, I got us a recording contract with Westport records in Kansas City, Missouri, and they want some rock ‘n’ roll records,” Alvis recalled. “He said he had five songs already written and all I had to do was go in there and sing. As far as I know Tony never sung or performed those songs on stage; he wrote them just for me. I had to sit down and drum them into my brain and learn them. I think it was probably Tony who suggested that I change my name from Wayne Samford to Alvis Wayne because he said Elvis has already got this thing going and your name is Alvis and all that. I said okay, whatever, you know more about this than I do so let’s go for it.”

Based in Kansas City, Missouri, Westport Records was established in 1955 by the Ruf brothers. The label released twenty-plus singles between 1955 and 1962 by artists such as Jimmy Dallas, Milt Dickey, Big Bob Dougherty, Lee Finn, The Home Folks, Elmo Linn, Ronnie & Marlene and Gene Chapman. Alvis and Lee Finn were the only artists that recorded rockabilly for Westport.

Alvis recorded not in Kansas City but only a few miles from his home in a converted, soundproof studio in a Corpus Christi machine shop. He cut his first sides in July 1956 with AI Hardy’s band backing him on three tracks of what Alvis thought was only a demo session. With Chuck Harrison on lead, Danny Walker on drums, Hank Evans on bass, Dusty Rhodes on steel, a blind pianist named Wally Bright and Alvis himself on rhythm guitar they recorded “Swing Bop Boogie”/”Sleep Rock-A-Roll Rock-A-Baby,” which was released as Westport 132. Both tunes feature astonishing steel work by Rhodes, who wrings some sci-fi sounds out of his instrument that surely would have impressed even steel virtuoso “Take It Away” Leon McAuliffe from Bob Will’s Texas Playboys. Not to be outdone, Chuck Harrison’s lead work is stinging, fiery and clever, betraying in its attack Harrison’s familiarity with Carl Perkins’s style. The other title, in a similar vein, was “I Gottum,” a solid midtempo rockabilly item notable for Wally Bright’s honky tonk piano flourishes and Alvis’s spirited, hiccupping vocal. This track would remain unissued for some 16 years

Alvis Wayne, ‘Swing Bop Boogie.’ Check out the wild steel work by Dusty Rhodes here. Released in July 1956, this was Wayne’s first single, recorded for the Kansas City-based Westport label.

Anthony (Tony) Wayne Guion’s Rhythm Wranglers are credited with accompanying Wayne on these tracks even though they were nowhere near the studio at the time. Wayne himself was puzzled by the credit and told an interviewer, “We will probably never find out the real reason why this was. Tony and I never had an actual owned paper type contract. We were friends and we worked together and he was trying to help me get fired up and get going and I went along with it all I could.”

Alvis’s first Westport record was released, apparently without his knowledge, in September 1956. Pressed at the King pressing plant in Cincinnati in both 45 and 78 rpm formats, the single was released with two different colored labels, one being the common red on white Westport colors, the other with the rarer silver on blue scheme. Despite frequent local airplay the single didn’t hit beyond the Corpus Christi area, selling some two thousand copies. Two months later Wayne returned to the studio for his second session. “Don’t Mean Maybe Baby”/”I’d Rather Be With You” (Westport 138), was to be Alvis’s biggest record, and was surprisingly released in England around 1959-1960, on the small Starlite label (Starlite 104). This label, operating from a basement in Bedford Avenue, West London, also released tracks by other rockabilly singers such as Aubrey Cagle and Curley Jim Morrison.

“Don’t Mean Maybe Baby” is one of the great obscure rockabilly records of all time. Released in late 1957, it bolts out of the gate on the strength of Harrison’s muscular, galloping lead guitar, picking alternate notes on the top strings a la Johnny Cash, but at a breathless pace, as Bright pumps away on the 88s and Wayne sings his frenzied come-on with the wild abandon of Carl Perkins in “Gone Gone Gone.” In his raucous solo midway through, Bright goes for broke, even throwing in a Jerry Lee glissando before he cedes the spotlight to Harrison for a quick, searing solo ahead of Wayne’s return.

Alvis Wayne, ‘Don’t Mean Maybe Baby’ (1956), the artist’s first Westport single and one of rockabilly’s great obscure records.

Cashbox took note of “Don’t Mean Maybe Baby” in a November 1957 issue, noting “The Westport label could have a hit on its hands with this terrific rock and roller, that Alvis Wayne drives out in dynamic fashion. It has the sound that the kids in all markets should go wild for. Now heading for the charts.”

The hit never materialized, but the single was surely Westport’s best selling record, but what is not speculation is its electrifying performance. Rockabilly aficionados properly recognize it as a genre classic.

“When I did those records,” Wayne recalled, “I thought I was just going in to do some demos to mail to Westport to see if they liked them, and if they did we would go back in and do the masters. From what I know Westport Enterprises was a real estate firm and I always thought that the record business was just a kind of hobby for its owner, Dave Ruf, and it was just something he liked fooling with in his spare time.

“I remember the day not long after we had recorded ‘Swing Bop Boogie.’ I was driving down the street in Corpus Christi listening to my radio and ‘Swing Bop Boogie’ started playing and I almost wrecked my car. I had goose bumps and I went through all different kinds of emotions because that was the first time I had heard it on the radio.”

Alvis soon became something of a local celebrity and he held the top chart spot in South Texas for six weeks, knocking a certain Hillbilly Cat out of the top spot. Its success, though, was strictly local, and Wayne recognized that. “The chart was mostly in South Texas,” Wayne said. “I don’t think it ever got over here to Houston because after I moved here several years later, nobody had ever heard of it. My records tended to be played by a lot of the small radio stations in the valley but at least it got me recognition on the Louisiana Hayride and we worked a live show out of Victoria every Friday night. “

A local fan called Laura Lee Fred (soon to become his first wife) had even started the Alvis Wayne Fan Club by recruiting members from Corpus and through out South Texas. He does not particularly have fond memories of wedded bliss first time round. “Obviously after I married her she became Laura Lee Samford but that didn’t last too long because I was always on the road and never at home and she was a young lady who needed attention. I don’t think I need to carry that any further.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ExVZ3xwOxQ

Alvis Wayne, ‘Sleep, Rock-A-Roll Rock-A-Baby’ (1956), the B side of ‘Swing Bop Boogie’

Wayne parlayed his local hit into regular work and toured quite extensively through out the South, working one-nighters in towns such as Houston, Edingburg, Beaumont, and Port Arthur. “We backed several star names because we were the opening act before the big names came on and did their thing. I knew Elvis; I worked with him on five separate shows and also on the Louisiana Hayride. I got to talk to him, although not for very long because the girls would keep pushing you out of the way tryin’ to get a kiss or whatever. But during the times we did get to speak I thought he was a real good old boy and he seemed a real nice guy to me. I also worked with Bob Luman, Johnny Horton, Slim Whitman and all the old timers back then as well as with all the package shows for the Hayride.”

With two singles under his belt and months of touring behind him, Alvis was set to return to the studio to cut what would turn out to be his final Westport release. A local white musician named James Bacon had a doo-wop-style group in Corpus Christi that would perform songs by artists such as the Platters, the Five Satins, the Flamingos, etc. In 1957 Bacon had written a song called “Lay Your Head On My Shoulder” but he couldn’t figure out the best way to approach the song. He offered it to Wayne for his forthcoming Westport session in Houston, and Wayne backed it with one of his few original tunes, “You’re the One.”

Wayne’s recollection of the session: “When we came to Houston the studio that we had been recording at in Corpus, well that old man shut it down and he wasn’t doing it there no more. Tony had phoned over to Houston and arranged a recording session, possibly at the Quinns or Melco studio. James Bacon had written ‘Lay Your Head On My Shoulder,’ offered it to me and said he would back me up on the record and that’s what he did. We made arrangements to go and there was a whole tribe of us, maybe three or four cars, and we drove over and did that session. Anyway, when I walked in there I sang this song for all these musicians I had never seen before in my life, but they were studio musicians and they knew what they were doing. I told them I wanna do this song and I want it to sound different. Then the drummer said wait a minute and he jumped up and went out the back door of the studio and there was a big pile of trash out there in the alley. He found an old bean pot and brought it back and sat on the stool and he started out beatin’ on the bottom of that old bean pot. That’s where that sound on the beginning of ‘Lay Your Head On My Shoulder’ came from.”

Alvis Wayne, ‘Lay Your Head On My Shoulder.’ The percussion sound at the beginning is the drummer beating on a bean pot he found in a pile of trash in the alley behind the Houston studio where the record was cut.

“Lay Your Head On My Shoulder”/”You’re the One” (Westport 140), released in early 1958, likely sold no more than a couple of thousand copies locally. Though the arrangement is lean and driving in the classic rockabilly style, Bacon’s group adding background harmonies gives it at least a tinge of pop much like the Jordanaires were doing on Ricky Nelson’s records at the time. The single’s tepid commercial reception disappointed Wayne, and his pessimism deepened when Tony Wayne went his own way, for personal reasons. “It got to a point where he couldn’t keep up with it anymore,” Wayne recalled, “and about that time he fell in love with this pretty little thing and got married. So he didn’t have time to fool with music anymore.”

In 1960 Wayne, then 22, joined the Air Force and spent the next four years training as a mechanic and obtaining his GED (General Education Diploma). Even while serving the country, though, Wayne continued performing when he could. He was stationed at Warner Robins air force base, which was about eighteen miles out of Macon, Georgia. While he was there he teamed up with Jimmy Harris and his band for a live, Saturday afternoon broadcast on WCRY radio and also played in Harris’s nightclub on evenings and weekends.

Nevertheless, Wayne could see he was heading towards a dead end professionally and his personal life was tumultuous—he was married and divorced three times between the ages of 18 and 22. “I became discouraged with my music before I went into the Air Force,” he told an interviewer, “and I was discouraged when I got out. Before I went in, I was so close to being where I wanted to be and when I came out four years later I could never get anything going again. I couldn’t get anything off the ground; it was just a battle. Then I started having kids, started thinking about making a living and that changed my whole world right there. I got married in late 1956 when I was eighteen years old. I got married again when I was 20 and I got married again when I was 22 and that one lasted for fourteen and a half years. Then there was a short break and I got married again and this one’s been twenty-three years now. I’m either growing up or I’m finding better wives.”

By the mid-‘60s Wayne had settled down and was working as a Braniff Airlines mechanic. On the side he fronted a small country outfit with local musician Lee Harmon, which sang in the bars and clubs in and around Corpus Christi. He even returned to the recording studio, albeit briefly, after a booking agent, O.B. O’Brian, signed him and the band after seeing a show in one of the Corpus Christi clubs.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HQHVx5MINgw

Alvis Wayne cuts loose on the risqué masterpiece, ‘I Wanna Eat Your Pudding,’ recorded for and released by Rockin’ Ronnie Weiser’s Rollin’ Rock Records in 1974

Inspired by this fortunate turn of events, Wayne returned to the studio in 1966 to cut two more singles he hoped would energize his music career. The first was “Storm in my Heart”/”I Don’t Believe I’ll Fall in Love Today” (Kathy 103); three years later, in ’69, came “Sweet Tender Care”/”A Million and Two” (Brozos 002). Both singles were released under his full name of Alvis Wayne Samford.

“I can recall those sessions with Lee Harmon’s band,” Wayne said. “He owned a big nightclub in San Antonio, which is where I was living at that time. The sessions only took about an hour and a half because I had been singing these songs with the band in the clubs so we didn’t have to practice. We just walked in there, turned on the tape recorder and did them. We couldn’t go out on the road at that time because I was working for Braniff Airlines full time, so we just played in the places we could get to at weekends.”

The next and final uptick in Wayne’s career strivings would not come until 1974, when Italian-born rockabilly fanatic Rockin’ Ronnie Weiser, founder of Rollin’ Rock Records, tracked down Wayne and pitched him on putting an EP together. With Texas rockabilly legend Mac Curtis present, Wayne cut three new sides “in my living room, with just me and my flat-top guitar.” These tunes included the risqué and often hilarious “I Wanna Eat Your Pudding”/”It’s Your Last Chance To Dance” (Rollin’ Rock’ 032) and “She Won’t See Me Cry Anymore,” the last of which appeared on the compilation Rollin’ The Rock Volume One (LP 009). “Pudding” even managed to find its way onto a Rollin’ Rock porn spoof, Teenage Cruisers (Rhino LP 016). The tapes were then taken back to Hollywood where Ray Campi overdubbed bass and percussion, Ronny himself added additional vocals and Jimmy Lee Maslon sat in on piano. The tracks on the Rollin’ Rock EP were “Sleep Rock ‘n’ Roll”/”Swing Bop Boogie”/”I Gottum” (finally, from 1956)/”Lay Your Head On My Shoulder” (Rollin’ Rock 012) and the reviews were uniformly positive.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=461-sbNmq9k

Alvis Wayne, ‘I Gottum,’ from his first session for Westport Records, July 1956 but unissued for 16 years thereafter.

Wayne soldiered on, working ten-hour days as a construction engineer for a company that builds oil refineries and chemical plants, while playing gigs on weekends. Having finally made a good choice in a wife (Fritzy), his children had given him three grandchildren to boot. He told the Rockabilly Hall of Fame’s John Kennedy that he was enjoying life, but added, “there’s still something missing.

“I have to be honest about this, but I still want to play music. I have not ever given up and I’m not going to give up until they start shoveling dirt on me. I think I still may have the chance to get one record in the top forty. I’m not shouting for number one, just the top forty will do me. I have several regrets, I’m sad to say. If I could go back and change anything I would never have got married the first time and I wouldn’t have had to worry about all that family stuff I gave up my music for and I just might have made it. But I just couldn’t keep myself from falling in love.”

In September 1994, Perry Williamson of Pink & Black Records issued the artist’s first long playing album. With the help of Ronny Weiser and John Beecher the LP gathered all of the Westport and Rollin’ Rock material (but, oddly, omitted “She Won’t See My Cry Anymore”) and included the unissued track “Heartbeat,” a slow country ballad that is believed to be an unissued Westport master cut at the first Corpus Christi session and likely written by Tony Wayne. Titled Swing Bop Boogie the LP also contains a so-called radio cut of “Pudding” (which now bears a Ronnie Weiser co-writing credit), although it sounds more like the standard 45 version but with extra studio chat added. (There are also some compilations that boast an alternative cut of “I Gottum” but only one version of this song was ever released).

In 2000 Ronnie Weiser got Wayne into Rollin Rock’s Las Vegas studio, backed by vocalist Jessica Rooth, acoustic bassist Fernando Anders Lopez, drummer David van Antwerp and, on lead guitar and piano, Billinghurst “Billy” Disonante (Jorge Harada is featured on guitar on “I Want You All The Time”). The ensuing full-length album, Rockabilly Daddy, caught reviewers’ attention, and in a good way. Writing at BlackCat Rockabilly Europe, a critic identified as The BlackCat gushed over the album. To wit:

The title track “Rockabilly Daddy,” written by Alvis, gives a pretty damn good first impression of the album. Straight Texas rockabilly, original 50s style with great authentic guitar licks by Billinghurst ‘Billy’ Disonante of Mack Stevens’ Hardcore Texas Cats fame. All tracks on this album have that distinctive Texas beat, some fast paced, others somewhat slower like the country styled “Those Lonely Lonely Teardrops” with female additional vocals by rockabilly filly Jessica Rooth. Johnny Horton’s “One Woman Man” perfectly displays Alvis’ deep soulful voice, a voice that was cut out to sing songs like this or the wailing country blues song “Here I Am,” written by Alvis’ wife Fritzie Samford. “A Good Woman’s Love” is a country ballad that reminds of earlier classics by Johnny Horton and Johnny Cash, while “Back To The 50s” is fast-paced rockabilly tribute to the founders of rockabilly music and to the time that this kind of music came naturally, the Fifties. “Fall Fallin” is a styleful tearjerker with beautiful high-pitched aaah’s and oooh’s by the aforementioned Jessica Rooth.

Alvis Wayne live, performing ‘Rockabilly Daddy’

Let’s have some more of that hardcore rockabilly. “You Can Have Her” is a great rocking Alvis & Jessica duet that will surely get your feet movin’. “Louisiana Dirty Rice” has some Cajun influences, no surprise of course if you know that it was written by Jimmy C. Newman, and Roger Miller’s “Billy bayou” is played somewhat faster than the original, which makes it a solid rockabilly song. More rockabilly beat on Rayburn Anthony’s “Gothenburg” and Faron Young’s “Alone With You”. Track 14 is another self-penned blues song with some great guitar by guest musician Jorge Harada. The closing song, “Texas Rockabilly Get Together,” has that same rockabilly style as the opening song, back to the roots of rockabilly.

A little something for everyone on this collection of Texas rockabilly, country, blues and cajun music, sung by a man who’s name can be uttered in one breath with the likes of Johnny Horton and Johnny Carrol. A great voice if I ever heard one! As Alvis Wayne states on the liner notes: “Texas rockin’ cowboys are the best!” Indeed!

In 2001 came Alvis Wayne’s last album-length statement, I’m So Proud of My Rockabilly Roots. Wayne had made it clear over the years that this album’s title was a serious matter to him, but the authority and feeling he brings to Ernest Tubb’s sarcastic classic “Thanks a Lot”; the intensity of his performance of the Johnny Horton-penned “Coated Love”; and the Marty Robbins-like heart tugging dramatics he employs on Billy Walker’s poignant “Cross the Brazos at Waco” show off his hard country side to good effect. Rockabilly fans got the best of Wayne here, though, in tough, driving performances of “Shame Shame Shame” (a white-hot putdown of a floozy featuring some searing guitar pyrotechnics); “I’m Ready If You’re Willing,” a sweet-natured come-on; and “Watcha Doin’ After School,” a throwback to an earlier era when school tribulations were fodder for pop hits, this one boasting some incendiary honky tonk piano work supporting Wayne’s free-swinging vocal. On the ballad side, Wayne is affecting as the lovestruck protagonist of the atmospheric “Sugar Coated Love” and suitably wounded as the aggrieved partner in a romantic debacle detailed in “One More Teardrop,” with a twangy guitar and a heavily echoed vocal adding to the production’s dramatic intensity.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p_OVo9OrrBI

From his last album, 2001’s I’m So Proud of My Rockabilly Roots, Alvis Wayne’s take on Ernest Tubb’s ‘Thanks a Lot’

Alvis Wayne Samford was preceded in death by his parents Alva and Nona Mae Samford, brother J.W. Samford, sister Barbara Samford Shadle and son Daryn Holland.

He is survived by his wife of 37 years, Fritzie Samford; a daughter, Pamela Samford of San Antonio; Chana Mills and husband Tim of Bacliff, and Faron Chace Samford of Bacliff. Five grandchildren: Jessica Samford, Taylor Holland, Madalyn Weaver, Chris Holland and Autumn Garza-Samford. Brothers Norvin Samford of Center Point, TX, and Robert Samford of Sealy, TX; and a sister-in-law, Elaine Samford, of Refugio, TX.

Sources: Wikipedia; “The Alvis Wayne Story” by John Kennedy posted online at the Rockabilly Hall of Fame website; Carnes Funeral Home.