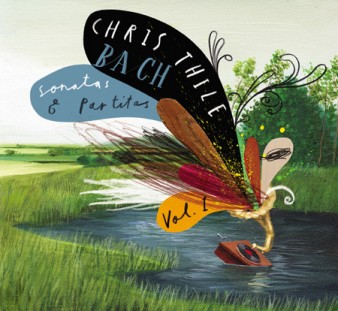

The unique experience of Bach as seen through the lens of Chris Thile’s performance (Photo: Matthew Spencer, www.matthewspencerphotography.com)

BACH: SONATAS & PARTITAS 1

Chris Thile

Nonesuch

First, a totally candid confession: I’m a classical musician deeply in love with Bach’s compositions, as well as a huge fan of Chris Thile’s previous work. As I cued up his debut classical album of Bach Sonatas and Partitas, I had high expectations for the results. Let’s say Thile delivered, and then some.

The program is comprised of the first three of the six sonatas & partitas for violin (Sonata No. 1 in G minor, BWV 1001; Partita No. 1 in B minor, BWV 1002; and Sonata No. 2 in A minor, BWV 1003), and presumably there will be a second disc coming along with the other three (Partita No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1004; Sonata No. 3 in C major, BWV 1005; and Partita No. 3 in E major, BWV 1006). It takes no small measure of confidence and ambition to take on any of Bach’s “big three” solo compositions (six sonatas & partitas for violin, six cello suites, and partita for solo flute), and Thile is at no loss for either of those attributes; to them he adds an abiding love for and sensitivity to the composer’s work, borne of his near-lifelong immersion in Bach’s music, which has informed almost everything he’s done from the first Nickel Creek album, throughout his solo career (which began when he was 13) and up to the present with the forward thinking Punch Brothers.

All of Bach’s solo works are incredibly challenging to perform. Playing the notes as the original scores dictate causes lesser musicians to break out in cold sweats. (I can only speak from experience in performing the cello suites, but it is sometimes almost comically apparent that they were written by someone accustomed to playing music with both hands and feet simultaneously!) Thile totally nails it here–his characteristically crisp, lithe, fleet fingered picking is nothing short of spectacular in fast-paced pieces such as the “Corrente” from Partita No. 1 in B minor.

Sonata No. 1 in G Minor, BWV 1001: II: Fuga; Allegro, from Chris Thile’s Bach: Sonatas & Partitas 1.

However, the true challenge presented by Bach is to play his pieces in such a way that their substantial soul and emotion isn’t lost in the complex and sometimes feverishly metric Baroque style. What I love about Thile’s own instrumental compositions and performing style is the rich emotional sweetness with which he imbues his music. He makes the mandolin sing—not merely by his impeccable technique and feel for tone and texture, but by letting it be a conduit for the joy this music gives him. In fact, his engagement with the compositions is quite spiritual, revealing an elevated sense of connection not only with the source material and its composer, but with the world at large–thus the “special sauce” of the full Bach experience Thile advances with profound, soulful conviction. In pieces such as the “Sarabande” from Partita No. 1 in B minor and “Grave” from Sonata No. 2 in A minor he deftly teases the emotion out of the music, capturing its sweet sadness in a way singular to his style.

As well (especially on instruments for which the music was not originally written) Bach’s notoriously spare notation of dynamics presents a daunting interpretive challenge. He largely let the architecture of the musical composition–along with how the instrument is physically used to perform those passages–dictate how loud or soft certain passages should be. So for the piece to really flower, the performer must be attuned to the nuances built into it in order to respond to the music and to his or her instrument.

An interview with Chris Thile prior to the release of Bach: Sonatas & Partitas 1, aired on PBS NewsHour, interviewer Jeffrey Brown.

Being a peerless mandolinist is one thing; what sets him apart from others practicing this increasingly popular instrument is his ability to use tempo and dynamics to their fullest dramatic potential (an art especially apparent in his work with the Punch Brothers). While there isn’t too much that can be done with the tempo in Bach (it’s Baroque, after all), instead of taking the usual route of letting himself be driven by tempo, he manages to take ownership of it, especially in the slower pieces such as “Adagio” from Sonata No. 1 in G minor. It’s impressively subtle, and somehow he’s been able to do it without undermining Bach’s distinctive Baroque style. No small feat. It’s Bach as performed by Chris Thile, not Chris Thile performs Bach.

Chris Thile performs Bach’s E Major Prelude in the 2009 documentary Bach & Friends by Michael Lawrence

At the Grey Fox Bluegrass Festival 2011, Chris Thile, performing on the Masters Stage, performs the Gigue from Bach’s D minor Partita

Even so, a few things do get lost in translation to mandolin. The most glaring absence is the delicacy and fluidity of a violin’s bow, which cannot be replicated by a picked mandolin. On some of the slower pieces, for instance, the double-, triple-, quadruple-stops and -rolls don’t feel quite as effortless and “intentionally unintentional” as they can with violin. This may be a matter of personal preference, but it’s a telling subtlety, and about the only blemish on an otherwise stellar outing by an artist who is committed to redefining his instrument in contemporary music much in the way Mark O’Connor–one of Thile’s most ardent supporters (in fact, O’Connor has called Thile “the greatest mandolin player in history”) and, indeed, the inspiration for Thile to pick up the mandolin in the first place–has done with the fiddle. A second volume of Thile-interpreted Bach cannot come too soon.

Christine N. Layton is a classical musician based in Ithaca, NY.