Author’s Note: When it comes to eateries, the name “MELS” instantly strikes a familiar chord with anyone who is a fan of George Lucas’s classic 1973 film, American Graffiti. The original drive-in that was a distinctive element in the film is, sadly, no longer standing. However, thanks to the everlasting popularity of Lucas’s tribute to his teenage years, the intriguing original structure that once stood in a large parking lot in San Francisco has become an icon and will long continue to be an object of fascination and appreciation for folks like myself. My self-professed obsession led me to investigate the drive-in’s history, and a rich history it turns out to be. I posted my findings in two parts on my website, Kip Pullman’s American Graffit Blog, in tribute to the original Mels Drive-In.

There’s No Place Like Mels

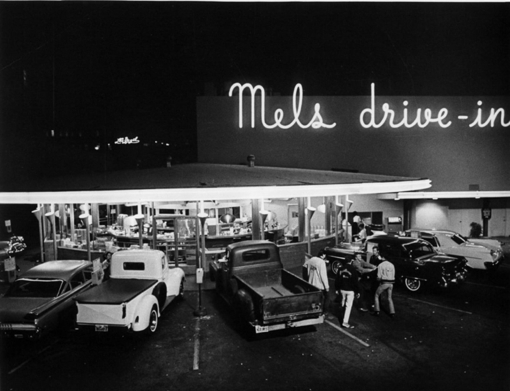

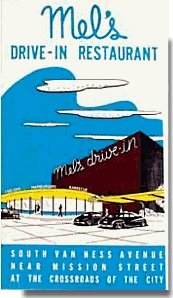

Anyone who has seen the 1973 film American Graffiti remembers the large neon sign buzzing in the background exclaiming Mels Drive-in. Mels, or Burger City (as it was referred to in the movie), was the hub of the gang’s activities, the place where all the characters converged and then fanned out on their respective adventures over the course of a single summer night in 1962. Even though the story is set in Modesto, California, the scenes at the carhop eatery were actually filmed at the very first Mels drive-in, formerly located at 140 South Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco, California.

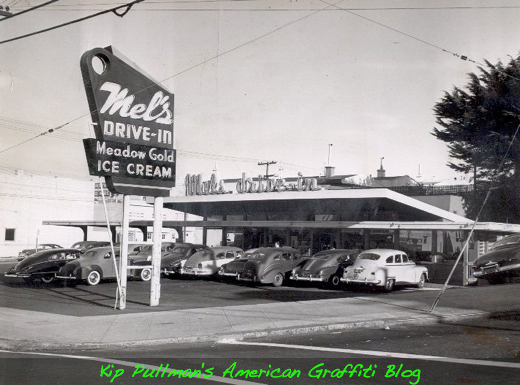

Although Texas lays claim to harboring the very first drive-in restaurant, California is where the concept really took off. Warm climate made eating in one’s car convenient; consequently most drive-ins in California first appeared in the southern portion of the state. However, in 1947, when the post-World War II economy was booming, Mel Weiss, along with San Francisco lawyer and politician Harold Dobbs, opened the first drive-in restaurant in San Francisco. According to Dobbs’s 1994 obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle, the restaurant was constructed by his father who was a professional carpenter.

In a 1991 interview with the Modesto Bee, Mel Weiss recalled that when the carhop eatery first opened he and his partner expected only modest success. Much to their surprise the restaurant was a hit from the start. “We did $120,000 the first month,” he recalled. If Mr. Weiss’s recollections are correct, the drive-in’s first month’s gross almost paid for the cost of building the entire restaurant, which was estimated to be approximately $135,000.

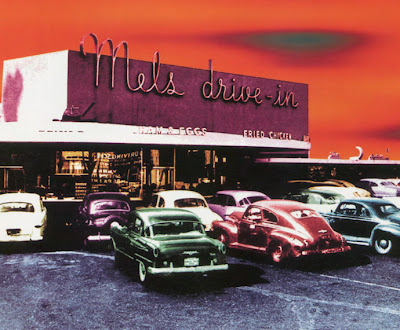

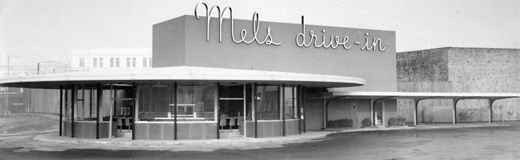

The original Mels Drive-In was at 140 South Van Ness Avenue near Mission Street. An ideal location, it consisted of ample grounds, attractively landscaped with capacity for 110 cars, and a two-story rectangular building. The distinctive Streamline Moderne structure had great expanses of glass wrapping around the circular dining portion of the building and orange tile around the foundation. Its round shape made it look like a flying saucer ready to spin off into outer space. And, like the aerodynamic wing of a jet, a roofing canopy (with smooth edges and recessed lighting) stretched alongside the rectangular portion of the building to cover cars. During the later part of the 1950s, the appearance of automobiles with flared, rocket-like tailfins were a perfect match for the building’s Space Age design.

The original Mels Drive-In was at 140 South Van Ness Avenue near Mission Street. An ideal location, it consisted of ample grounds, attractively landscaped with capacity for 110 cars, and a two-story rectangular building. The distinctive Streamline Moderne structure had great expanses of glass wrapping around the circular dining portion of the building and orange tile around the foundation. Its round shape made it look like a flying saucer ready to spin off into outer space. And, like the aerodynamic wing of a jet, a roofing canopy (with smooth edges and recessed lighting) stretched alongside the rectangular portion of the building to cover cars. During the later part of the 1950s, the appearance of automobiles with flared, rocket-like tailfins were a perfect match for the building’s Space Age design.

With an indoor customer capacity of 75 people, the interior was typical diner style with plenty of Formica tabletops and booths framed in chrome and upholstered with orange Naugahyde. In the center of the main floor, a row of stools faced a circular dining counter that wrapped around two complete soda fountains and a battery of pie cases and coffee urns. The original cooker had the ability to turn out 180 hamburgers per minute. A large staff of cooks, dishwashers, and servicemen were part of the Mel’s staff that kept their business thriving.

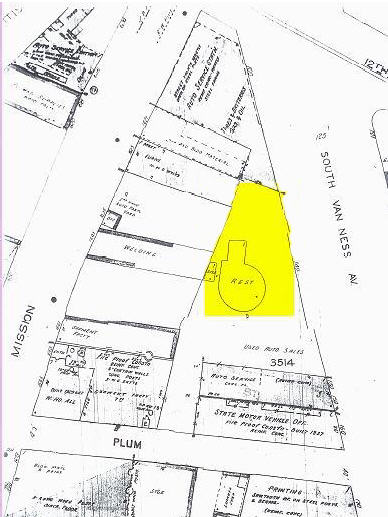

1948 Fire Map

The 1948 fire map above shows that Mel’s drive-in (highlighted area) was surrounded by a used car dealership, service station, welding shop and other businesses with streets that received plenty of traffic. The property included a huge parking lot to accommodate many customers.

More of a Good Thing

Motivated by the success of their first drive-in, Mel Weiss and Steve Dobbs opened their second Mels around 1952. Located at 3355 Geary Street near Beaumont St. in San Francisco, the drive-in employed Weiss’ son, Steve, who worked as a soda jerk during high school and then later operated the restaurant.

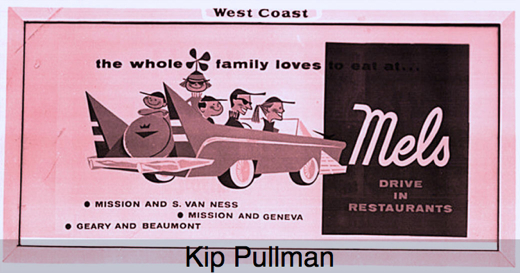

In the mid-1950s California became the state with the highest rate of automobile ownership in the nation. Witnessing the growth of the car culture, Mel Weiss and Harold Dobbs began expanding the San Francisco car service-based restaurant into a successful chain. By 1954 the Mels franchise was pulling in about $4 million annually. It was estimated by Weiss that they were cooking up 15-20,000 hamburgers a day. But the menu consisted of many more items than the Melburger. Along with the usual beverages, desserts and fountain specials, the Chicken Pot Pie for .85 cents was a popular item. In fact, the choices of American-style food were almost endless. Depending on the individual restaurant location, one could order Half Fried Spring Chicken (like mother used to make), Roast Young Tom Turkey, Fried Jumbo Prawns, a Chef’s Salad Bowl, Thick Top Sirloin Steak & Eggs with potatoes or sandwiches such as the Mels’ Pore Boy (with a full pound of choice ground beef on a quarter loaf of French bread and served with salad).

Waitresses at the Mels on Geary Street pause to smile for the camera. The location became a Pacific Stereo store for many years beginning in the late-1970s, but then reverted to its iconic self once more in 1984.

Mels became a fixture of contemporary life, with lurid neon lighting, carhops, and a pre-fast food menu. During the 1950s and ’60s you could find one or more Mels drive-ins located throughout Northern California, in San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, Sacramento, San Jose, Walnut Creek, and Salinas.

At one point Mels also ran several bowling alleys and restaurant complexes and even branched off into a second chain called KINGS. The Kings restaurants were located on the Peninsula south of San Francisco.

During the 1950s Mels was a thriving franchise, an example of capitalism at its best. But as turbulent ‘60s unfolded, its reputation would not go unscathed.

Mels Drive-In: The True Story (Part 2)

Preface

I received a lot of positive feedback on Part 1 of this history. I even received an e-mail of praise from Steven Weiss, son of Mels founder Mel Weiss. Steve, with his business partner Donald Wagstaff, brought back the Mels Drive-In restaurants in the mid-1980s with the initial diner on Lombard Street in San Francisco. It was very flattering to receive positive recognition from him.

Before we get to the meat of this post I’d like to preface it with two things. First, if you haven’t read Part 1, I suggest you turn your happy ass around and do that before digging into Part 2. Second, I want to present some clarification and a bit of an introduction to what is sort of a mini-San Francisco Bay Area history lesson. When we think about and discuss America in the 1950s we tend to associate the era as a pleasant time when things were much simpler and teen culture was defined by greasers, hot-rods and rock and roll music. Indeed, those were great times, but not for everyone. If you were African American, you faced bigotry and discrimination from a society that was ruled by those who were predominantly male and pale. Your chances of finding a good job were extremely thin even though the African American freedom struggle was working hard to revolutionize American race relations long before the ’50s were out. So as we explore this second chapter of “Mels Drive-In: The True Story Of The World’s Most Famous Diner,” it only makes sense to discuss how the restaurant was affected by some of the historical events that took place during the Civil Rights movement of the early ’60s. The latter part of this post looks at the restaurant’s starring role in American Graffiti and the eventual demise of the original Mels. Nuff said. Start reading.

A patrol car cruises past Mels (bottom left). This scenario would be replicated 15 years later in American Graffiti.

The Times They Are A-Changin’

In the early 1960s, Mels Drive-In was a place of controversy as it became the location for the first mass sit-in of the San Francisco Bay Area Civil Rights movement. This distinction is one that Mels owners would probably rather forget. In the Fall of 1963, a group of young people calling themselves the Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination first picketed and then organized a sit-in at all three of the Mels Drive-Ins in San Francisco. Many of these demonstrators were students at Cal Berkeley or S.F. State who were protesting management not hiring Black personnel to work in “visible capacities” such as carhops, waiters, waitresses, bartenders, and cashiers. The picket lines first appeared in October as activists carried signs with slogans such as, “Where are the Negro Waitresses?” and “Don’t Drive-in, Drive-out Segregation.” By the first weekend of November the protest had evolved into the first mass sit-in of the Bay Area Civil Rights movement. Although new to many, it was a classic form of non-violent disruption; all the actions were legal but they significantly interfered with the drive-in’s ability to conduct business. Mels was not the only Bay Area establishment to be affected by mass demonstrations. A month or so earlier demonstrations at the Sheraton-Palace Hotel in San Francisco had highlighted its discrimination against blacks, and following the demonstrations at Mels, Lucky’s supermarkets became the target of large anti-discrimination protests.

‘One cup of coffee and six straws, please!’ Protesters occupied all the seats in Mels Drive-in and refused to order. More than 100 were arrested.

Mels co-owner, Harold Dobbs, was a San Francisco Supervisor running for Mayor of San Francisco at the time and some believe that the demonstrations were politically motivated because the protesters used the weekend before the mayoral election to demonstrate. In addition, local newspapers noted that protesters chose to picket in front of Dobbs’s home but not the home of co-owner Mel Weiss. Organizers of the demonstration denied any political motivation. It is not clear as to what effect the protesters had on his campaign but Dobbs lost the election to John Shelly. One week later, management settled its dispute with the protesters by agreeing to hire and train Black employees in “up front” positions. Some Black carhops and bartenders were hired immediately. The agreement was reached only five minutes before 200 protesters had planned to picket and stage a sit-in at a Mel’s Drive-In located at 2300 Shattuck Ave. in Berkeley. So, even though their discriminatory hiring practices initially echoed a negative mindset typical of the 1950s, Mels was, conversely, one of the first establishments to alter its hiring policies in fairness to African-Americans, which reflected the awareness and open-mindedness that the Civil Rights movement helped usher in.

Although Civil Rights protests at Mels had briefly threatened business, the jeopardy it had faced was miniscule compared to what the future held for carhop restaurants. Mels continued to reign without conflicts or major competition for almost 10 years but fast-food hamburger chains eventually squeezed out their service. McDonald’s was the biggest culprit. With its limited menu and a self-service ordering system McDonald’s had established itself as the undisputed leader of the fast food industry. By 1970 The McDonald’s empire consisted of 1,500 franchised outlets and was quickly growing.

Mels Drive-Ins with carhop service were pushed out of business by fast-food chains such as McDonalds. (photo from 1962)

A Drive-In By Any Other Name…

By 1972 Weiss and Dobbs had sold the Mels franchise to the Foster’s chain. It was during this year that the location manager for American Graffiti, Nancy Giebink, began scouting a location for a building to represent a drive-in called Burger City in the film. The 140 S. Van Ness location came to her attention and arrangements were made through Dennis Kay, Director of Operations for Foster’s West, to lease the restaurant for the film.

Graffiti co-producer Gary Kurtz recalls the drive-in being run-down when they first leased it. “It was in terrible shape,” he said. “We had to repair the neon in the signs and repair the light bulbs and paint it. When [cinematographer,] Haskell [Wexler] saw it for the first time, he decided, since we were going to do so much shooting there, to replace the light bulbs with photofloods.” In addition, the neon letters that spelled COCKTAILS on the large street sign (under the arrow) were replaced with the words BURGER CITY to match the burger shack that was described in the American Graffiti script. Ironically, in the film the restaurant is always referred to as “Burger City.” No one ever calls it “Mels.” The name “Burger City” is a twist on the popular 1950s slang term “Fat City,” meaning a great thing or place.

Graffiti co-producer Gary Kurtz recalls the drive-in being run-down when they first leased it. “It was in terrible shape,” he said. “We had to repair the neon in the signs and repair the light bulbs and paint it. When [cinematographer,] Haskell [Wexler] saw it for the first time, he decided, since we were going to do so much shooting there, to replace the light bulbs with photofloods.” In addition, the neon letters that spelled COCKTAILS on the large street sign (under the arrow) were replaced with the words BURGER CITY to match the burger shack that was described in the American Graffiti script. Ironically, in the film the restaurant is always referred to as “Burger City.” No one ever calls it “Mels.” The name “Burger City” is a twist on the popular 1950s slang term “Fat City,” meaning a great thing or place.

Filming at Mels began on Monday, July 10, 1972, and continued for the following two days. During the nights of filming, the restaurant was closed for business but re-opened in the morning. The crew returned the following Monday on the 17th to film the interior scenes and exteriors such as Curt talking on the phone. Unfortunately, in the process Lucas’s expensive Eclair camera fell off the tripod, damaging the camera and some of the film and necessitating an extra day of filming, on August 2, for some exterior shots.

The outfits worn by the carhops in the film (including roller skates) were not typical garb for the Mels employees.

I spoke with the film’s set decorator, Douglas Freeman, a few years back and he conveyed an amusing anecdote that took place when they were filming at the restaurant. Apparently, he and “Woody” (Prop man, Dale Woodall) had an attack of the “munchies,” and this led to some indulgent behavior. “We went crazy in their kitchen and started making all sorts of sandwiches, burgers, and ice cream floats for the crew and ourselves,” he remembered. “Without really thinking about the consequences, we’d eaten several hundred dollars worth of their food and when the drive-in opened up the next day they lost a lot of business because they were out of so many things,” he said with a chuckle and then added, “Needless to say the management was not too happy.”

I asked Freeman about the tasks he had while working on-location at the restaurant. Since Mels did not use intercoms at its restaurants Freeman had to build about 10 non-functional intercoms to be used as props in the film. “To make the base I simply used a large outdoor umbrella stand. Those bases were extremely heavy. I remember carrying one and dropping it on my foot and breaking a toe,” [Laughs] Incidentally, because the intercoms did not actually work, the voices heard emanating from them in the film were added in post-production.

The tall trees to the right and precarious camera positioning helped to obscure the fact that the drive-in was not located in a small California town, such as Modesto but, rather in the enormous city of San Francisco.

Some time after filming had completed, Foster’s eventually filed for bankruptcy and the restaurant was sold once more. Contrary to what’s previously been written about the original drive-in, it did not close down immediately after filming. The eatery was open several more years before it met its demise and was torn down.

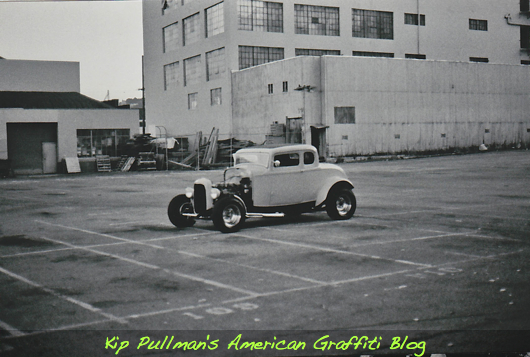

Longtime Milner Coupe owner Rick Firgari shared a couple of incredible pics of the movie car parked at the location of the first Mels in a parking space after the restaurant had been torn down. The large building, in the background can be briefly seen in some of the daytime scenes in the film. This pic was taken facing south sometime around 1986.

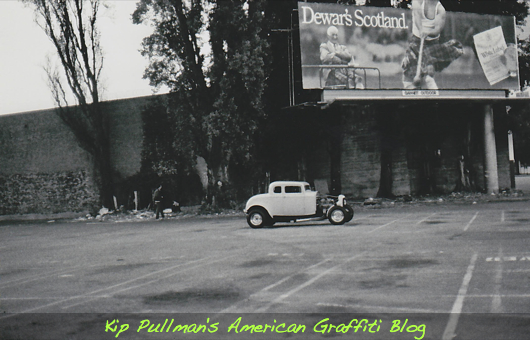

Another shot of the coupe diminished in size by the enormity of the lot that once held the legendary super drive-in. The photographer was facing north for this pic. The surrounding walls and trees no longer exist but are familiar landmarks seen in old pics of the restaurant, and in the opening scenes of Graffiti. The billboard advertising Dewar’s Whisky is a post-Mels addition to the lot.

The location where the first Mel’s once proudly stood was a vacant lot for a lengthy amount of time. In 2002 it became the permanent locale for an 11-floor, 212 unit high-rise luxury condominium development. To the right is a Chevron Car Wash that takes advantage of its angled corner location by allowing customers to enter the wash on Van Ness Ave and exit with a clean vehicle on Mission Street.

Fortunately, Mels Drive-In, at 140 S. Van Ness in San Francisco, with its dramatic structural form and dazzling neon, has been preserved in George Lucas’ classic film. And the popularity of the film has helped to establish Mels as an icon of mid-century American popular culture. In addition, the “Next Generation” Mels Drive-Ins and Mels Diners, which first opened in the mid-’80s, have assured that the name, spirit, sights, and sounds of the original eatery are alive and well for many people to enjoy.

NOTES (Part 1)

Bayer, Patricia. Art Deco Architecture. London: Thomas and Hudson, Ltd., 1992.

“Burger Chain Delivers Mels on Wheels Cruising Modesto.” The Modesto Bee. Oct. 5, 1991.

California Living Magazine, November 20, 1983.

Freeman, Jo. “From Freedom Now! to Free Speech: How the 1963-64 Bay Area Civil Rights demonstrations Paved the Way to Campus Protest.” Website. Retrieved 8/13/2012. http://www.jofreeman.com/sixtiesprotest/baycivil.htm

Freeman, Jo. At Berkeley in the Sixties: Education of an Activist, 1961-1965. Indiana University Press

Hurley, Andrew. Diners, Bowling Alleys and Trailer Parks. New York: Basic Books, 2001.

Mels Drive-in Web Page. Retrieved 8/12/2012. www.melsdrivein.com.

Obituaries. San Francisco Chronicle. August 18, 1994. “H. Dobbs, Began Famed Drive-in Eatery.” Sun Sentinel.com Retrieved 1/27/2013. http://articles.sun-sentinel.com/1994-08-18/news/9408170431_1_mel-s-drive-in-restaurant-san-diego-mel-weiss

Online Archive of California; Specialty Real Estate Web Page. Retrieved Sept. 6, 2012. www.specialtyrealestate.com/issues/nov98/aclassickeepsonrockin.htm

NOTES (Part 2)

Bayer, Patricia. Art Deco Architecture. London: Thomas and Hudson, Ltd., 1992.

“Burger Chain Delivers Mels on Wheels Cruising Modesto.” The Modesto Bee. Oct. 5, 1991.

California Living Magazine, November 20, 1983.

Figari, Rick. 1986. Photographer. Pictures of ’32 Coupe in former Mels parking lot.

Freeman, Jo. From Freedom Now! to Free Speech: How the 1963-64 Bay Area Civil Rights demonstrations Paved the Way to Campus Protest. Website. Retrieved 8/13/2012. http://www.jofreeman.com/sixtiesprotest/baycivil.htm

Freeman, Jo. At Berkeley in the Sixties: Education of an Activist, 1961-1965. Indiana University Press

Hurley, Andrew. Diners, Bowling Alleys and Trailer Parks. New York: Basic Books, 2001.

Mels Drive-in Web Page. Retrieved 8/12/2012. www.melsdrivein.com.

Online Archive of California; Specialty Real Estate Web Page. Retrieved Sept. 6, 2012. www.specialtyrealestate.com/issues/nov98/aclassickeepsonrockin.htm

Picketers photograph: San Francisco News-Call Bulletin newspaper photograph archive. Retrieved 8/10/2012. http://content.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/hb9w1009k9/?order=3&brand=calisphere

The history of Mels Drive-In is but one of the many pleasures awaiting American Graffiti fans upon visiting Mark Groesbeck’s Kip’s American Graffiti Blog. Entirely researched and written by Mr. Groesbeck, it includes a wealth of information about various aspects of George Lucas’s movie classic, including features on the cars of American Graffiti; a profile of Wolfman Jack; and a fascinating “where are they now” feature on some of the actors who played lesser but nonetheless memorable roles in the story.

Many thanks to Mark Groesbeck for permission to reprint his Mels history as part of the Deep Roots 40th anniversary salute to American Graffiti.