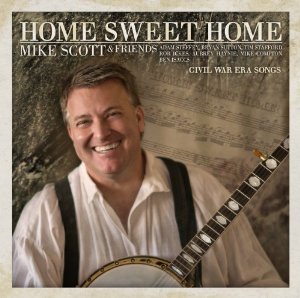

HOME SWEET HOME: CIVIL WAR ERA SONGS

Mike Scott & Friends

Rural Rhythm

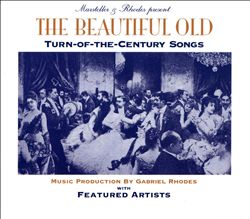

THE BEAUTIFUL OLD

Various Artists

Doubloon Records

As the 150th anniversary of the Civil War rolls on (2011-2015), this year marking the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation, the First Conscription Act, the Battle of Gettysburg and the ensuing Gettysburg Address, Vicksburg, Chickamauga, Chancellorsville, the Battle of Chattanooga and the Siege of Knoxville.

Artists on the Rural Rhythm label are in the midst of their own multi-volume commemoration of the War, and with the release of Mike Scott’s all-instrumental tribute, Home Sweet Home: Civil War Era Songs, they’re batting 1.000, two for two, in a stirring follow-up to the label’s first volume in this series, the acclaimed God Didn’t Choose Sides: Civil War Stories about Real People, Vol. 1 (this publication’s Album of the Week, April 11, 2013). In contrast to that earlier volume, Scott’s entry in the series is comprised not of original songs penned by contemporary writers (and all based on, as the title says, real people and how the war affected them) but of songs that mostly pre-date the war years (and one from the late 20th century!) but had never gone out of style with the troops or the general populace–this was not a time of one-hit wonders or disposable pop but of tunes treasured for their sentiments expressing heartfelt human longings or strivings and unabashed sentimentality offering an escape from realities untenable at the time they were written and, obviously, more so once the first shots were fired on Fort Sumter at 4:30 a.m. on April 12, 1861. Arguably the most amazing fact about Scott’s 14 selections is how many of them have endured as roots standards–such as “Soldier’s Joy” (a happy number with, in its lyrics, a dark penumbra describing substance abuse among the troops) and “Bonaparte’s Retreat,” to name but two–and how a few others, or at least “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” are part of America’s national fabric, and perhaps are being sung somewhere every day.

Scott, one of the banjo’s finest practitioners, and the all-universe band he’s assembled for this project–Tim Stafford, Adam Steffey, Bryan Sutton, Aubrey Haynie, Mike Compton, Rob Ickes, Jeff Taylor, Scott Miller and Ben Isaacs–tell their stories in pure musical dialogue, in the arrangements’ rich, shifting textures; in the clear, ringing tones and precision picking and bowing of their instruments; in the rousing conversations they have following or bouncing off each other in dynamic solo passages. Theirs is virtuosity with soulful expressiveness.

Promotional video for The Beautiful Old. Includes snippets of ‘The Band Played On’ (lead vocal: Richard Thompson), ‘The Flying Trapeze’ (Graham Parker); ‘Beautiful Ohio’ (Kim Richey, Garth Hudson on piano); ‘After the Ball’ (Dave Davies); ‘Silver Dagger’ (Julie Goodnight, with Richard Bowden on fiddle, Gabriel Rhodes on guitar).

The Beautiful Old, on the other hand, offers the haunting neo-Victorian language of early American popular songs in its 19 offerings ranging from 1805’s “The Last Rose of Summer,” a wistful instrumental version of a poem by Thomas Moore (friend of Shelley and Byron) originally set to music by Sir John Stevenson and since interpreted by everyone from Beethoven to the Grateful Dead, to two tunes from 1918, obviously well after the Civil War ended. What it has in common with Home Sweet Home is the window it offers into a lost world of civil discourse, graceful, beckoning melodies, and genteel lyricism reflecting the rise of a distinctly American voice and temperament (with the post-Civil War diminishing of the Anglo influence). It’s a wondrous moment, even more wondrous in not relying on a single Stephen Foster song to heighten its impact.

The brainchild of producer Paul Marsteller and heralded multi-instrumentalist Gabriel Rhodes (who, interestingly, helped produce the 2005 Grammy winning Best Traditional Folk Album, Beautiful Dreamer: The Songs of Stephen Foster, and whose mother, singer-songwriter Kimmie Rhodes, is one of the album’s stars), The Beautiful Old was a year-plus in the planning but the wait was worthwhile, because it seems all the right pieces are in the right places here. Clearly one of the smartest moves was to bring in The Band’s Garth Hudson on accordion and keyboards, then sit back and let him masterfully steer various reed and string ensembles to a higher artistic plane. As vocalists Marsteller and Rhodes looked well beyond the Americana Music Association roster you might have expected to be well represented on a project such as this. Instead they’ve gone for some grit to buttress the softer, wistful moments by enlisting the likes of English pub rocker Graham Parker to jubilantly growl his way through “The Flying Trapeze”; the Kinks’ Dave Davies to add unusual, boozy sizzle to rouse “After the Ball” (from 1895) from its normally sedate presentation; and folk icon Eric Bibb taking his cue from his family friend Paul Robeson in unleashing his warm baritone on a bluesy reading of “Just a-Wearyin’ for You,” first published in 1901 and written by Carrie Jacobs-Bond, whose other early popular song monuments are “I Love You Truly” and “A Perfect Day.” Garth Hudson is the closest to a household name the musician lineup offers, but this album doesn’t need star power; it needs what it has, and that’s a sure-handed feeling for the emotions expressed in these songs. Yes, Jimmy Lafave’s version of the touching “Long Time Ago,” from 1839, has the rustic flavor of early traditional country music from the next century, but Lafave’s dry, reedy, sincere vocal, as underscored by Floyd Domino on piano, Richard Bowden on violin, Brian Standefer on cello and Kimmie Rhodes on harmony vocals, nonetheless has the power to move souls even as it proves the validity of its updated sound and style and, not incidentally, the influence this style of song had on the language and subject matter of early country music.

That the female voices are the standouts here is unsurprising. So many of the sentimental songs and the language of those songs seem designed for a softer, more tender–and sometimes chillingly fatalistic–soprano or mezzo-soprano. The aforementioned Kimmie Rhodes dazzles every time she comes around, starting with the also-aforementioned “A Perfect Day,” a note-perfect 2:27 of sighing vocal and spare, atmospheric support from Gabriel Rhodes’s somber guitar (and his melodica, pump organ and glass armonica) and Ruby J. Hornsby’s understated violin and voila, all servicing a reflection on newfound friendship; Garth Hudson’s moody piano and Jon Mills’s low humming clarinet set the stage for Rhodes’s swooning reading of “Somewhere a Voice is Calling,” a hopeful treatise on love impending from 1911 (you don’t have to listen closely to hear snippets of a familiar melody that sounds a lot like “A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes,” from Walt Disney’s Cinderella, in 1950). A beloved standard from 1910, “Come Josephine in My Flying Machine,” is a fanciful take on what was then new technology–the flying machine–and the opportunities for courtship it offered, the song was first recorded as a duet and so it is here, with Will Sexton providing the gentle come-on vocal and Simone Stevens singing the part of the reticent but wonderstruck love interest who cautions her partner, when once aloft, “Whoa, dear, don’t hit the moon,” to which he offers a sly rejoinder, “No, dear, not yet but soon.” All this is set to a delicious period arrangement replete with fluttering woodwinds and reeds, soft percussion (courtesy Soupy’s son, Hunt Sales) and temple blocks (Dony Wynn, adding to the graceful arrangement). No such gentility attaches to Jolie Goodnight’s stern treatment of the old warhorse “Silver Dagger,” a woman’s warning to her suitor of her mother’s homicidal intent–“she says I can’t be your bride”–and her decision “to sleep alone all of my life,” dire warnings set to a hard driving arrangement featuring only Richard Bowden’s anxious, jittery fiddling and Gabriel Rhodes’s galloping guitar (and, at the start, a lonely hammered dulcimer); Carrie Elkin, with Kimmie Rhodes harmonizing, follows with an exquisitely aching take on “The Dying Californian,” a tale from 1854 recounting a dying sailor’s last words to his family at the end of a journey he thought would bring riches but gained him only “an orphan’s portion,” cost him his family and, ultimately, his life. Bowden’s violin, crying and moaning, conjures the proper feeling of resignation and sorrow the old sailor expresses.

AUDIO CLIP: Carrie Elkin, The Dying Californian, from The Beautiful Old (Richard Bowden, violin)

09 Come Josephine In My Flying Machine

Two wonderful instrumentals close the proceedings, the first being a string-enhanced “The Last Rose of Summer,” another showcase moment for Bowden to tug mightily at the listener’s heartstrings with an exquisitely aching solo. The album’s sign-off number dates from 1918, was written by Richard Whiting, and puts us at the doorstep of a new American voice in songwriting, one that retains some of the sound of the 19th century refrains we’ve been hearing–thanks to Garth Hudson’s accordion and Gabriel Rhodes’s piano–but also reveals a looser rhythmic structure, a slightly more pronounced swing in an altogether striking performance that flits by in a quick 2:08 but perhaps tells us much in its title: “Till We Meet Again.” Let’s hope we do.

Mike Scott’s album offers a real education in song etymology, as almost all of its tracks have deep roots in 18th and early 19th century (and possibly even earlier) tunes of Irish and Scottish derivation. The lively workout on the opening track, “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” introduces listeners not only to the album but to its dramatic personae. Scott, on banjo; Aubrey Haynie, on fiddle; Rob Ickes on dobro; Adam Steffey, on mandolin; Tim Stafford, on guitar; Jeff Taylor on pennywhistle and accordion each get a go-‘round with the melody, as Ben Isaacs keeps the bottom solid on upright bass. The first known printed text of the song appeared in a Dublin, Ireland, publication in 1791; the earliest known version of the melody was published in 1810; and it had been through numerous variations before the U.S. regular Army adopted it during the War of 1812–after a soldier had heard a British prisoner singing it–and embraced it as a marching tune through the 19th century. The Union and Confederate Armies fashioned their own versions with different lyrics, with the latter army taking pains to skew Abraham Lincoln in verses such as “Jeff Davis is a gentleman/Abe Lincoln is a fool/Jeff Davis rides a big white horse/And Lincoln rides a mule.” Scott and his cohorts don’t take sides, theirs being an instrumental, but rather use it as a benchmark for the mostly upbeat, high spirited frolics yet to come. The song had such a life, in fact, that it insinuated itself into 20th century popular culture when it was used in the closing sequence of the 1940 Bugs Bunny cartoon, “A Wild Hare.”

Bugs Bunny, ‘A Wild Hare’ (1940). At the end, Bugs marches off into his rabbit hole playing ‘The Girl I Left Behind’ on the fife (okay, a carrot doubling as a fife). Mike Scott includes a fine version of ‘The Girl I Left Behind’ on his new album of Civil War-era instrumentals, Home Sweet Home.

And there is the rub: for all the ongoing horrors of the Civil War, an abundance of cheery music could be heard from both camps. That would not be the case, however, with the title track, “Home Sweet Home,” which dates from the 1823 opera Clari, Maid of Milan by American playwright John Howard Payne with a melody by Sir Henry Bishop drawn from an old Italian folk song. Even though Scott and friends take it at a brisk pace, established by Scott’s energetic banjo and Haynie’s soaring fiddle work, back in the day in question the song was a heart tugging ballad that the Union Army banned from being played, for fear of its lyrics’ longing for the sanctity and safety of home and family inciting a rash of desertions. The Confederate leaders had no such qualms obtaining from Rebel soldiers’ affection for the tune. It also was a favorite of President Lincoln’s, who requested it be performed at an 1862 White House concert by opera singer Adelina Patti.

“Turkey In the Straw”’s history is rooted in its origins as a racist “coon” song in the late 1820s or early 1830s but more benign lyrics were published in 1862 and various versions of it surfaced during the Civil War (including some with obscene lyrics). In the 20th Century its melody was featured in a scene in the first cartoon starring Mickey Mouse, “Steamboat Willie,” which was also one of the first successful synchronized animated sequences in cartoon history. Aubrey Haynie takes flight on the fiddle to kick off the version here, with Rob Ickes coming up fast behind him in dobro ahead of Adam Steffey’s mandolin charge that gives way to another rousing Haynie solo in what is one of the album’s most dazzling displays of instrumental camaraderie.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BBgghnQF6E4

Mickey Mouse, ‘Steamboat Willie’ (1928), using ‘Turkey in the Straw’ in one of the first successful synchronized animated sequences in cartoon history (begins at 4:22).

AUDIO CLIP: Mike Scott & Friends, ‘Turkey In the Straw,’ from Home Sweet Home: Civil War Era Songs

The beloved fiddle tune “Bonaparte’s Retreat” has been traced to the tune of an Irish march, “The Eagle’s Charge,” with the most popular version being one with lyrics penned by Pee Wee King in 1950. An interesting iteration of the tune is found in its use by American classical composer Aaron Copland as the basis of the “Hoe-Down” movement of his 1942 ballet, Rodeo. Copland’s version, almost exactly copies the melody and rhythm of a 1937 recording of the tune by old-time Kentucky fiddler Bill Stepp, who was described by folklorist Alan Lomax, in an October 26, 1937 letter to his supervisor at the Library of Congress, Harold Spivacke, as “the best fiddler I have heard in Ky.” Scott and the fellows actually take their rendition at a more moderate pace than some others have of late, which serves to underscore a beautiful melody enhanced by measured solos by Scott on banjo, Steffey on mandolin and Ickes on dobro.

Old-time Kentucky fiddler Bill Stepp’s 1937 recording of ‘Bonaparte’s Retreat.’ American classical composer Aaron Copland used Stepp’s version as the basis for the ‘Hoe-Down’ movement of his 1942 ballet, Rodeo.

A scene from Buster Keaton’s film Go West set to the ‘Hoe-Down’ movement from Aaron Copland’s ballet, Rodeo.

AUDIO CLIP: Mike Scott & Friends, ‘Bonaparte’s Retreat,’ from Home Sweet Home: Civil War Era Songs

In 1861, Confederate President Jefferson Davis declared: “Our cause is just and holy,” and the South embraced as its motto Deo vindice (”God will vindicate us”). In the same year, New York City-born, Boston-based, anti-slavery poet Julia Ward Howe composed the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” firing a warning shot back at the south for its transgressions in lyrics such as: “He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword. … I have seen Him in the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps. … Glory, glory Hallelujah, His truth is marching on.” In his book Upon the Altar of the Nation: A Moral History of the Civil War, Harry S. Stout, in examining the moral underpinnings of the War Between the States, documented the activist role preachers on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line played in inflaming the passions of their flocks to support their respective causes, casting it as a Holy War, not a Civil War. Post-Civil War the song has been accepted as one of America’s finest patriotic songs and is performed seemingly everywhere on Independence Day, its origins and purpose only dimly remembered now. Perhaps celebrating the song’s liberation from partisan issues, Scott & Friends take their version at a moderate uptempo pace, with genial solos all around from the assembled cast, that seems designed less as a celebration and more as an acknowledgement of how hard won was its current respect as a song of union, not Union.

04 Battle Hymn Of The Republic

The only contemporary song on the album is one that has always seemed like it must have been written in the darkest hours of the Civil War, Jay Ungar’s ever haunting “Ashokan Farewell.” You can’t say it doesn’t belong here–it’s arguably more appropriate than some of the songs from the actual timeframe for what it’s come to symbolize since its legend was sealed when Ken Burns used it as the theme for his epic The Civil War documentary, in which it served as the searing background music for the series’ most famous scene, the reading of Sullivan Ballou’s letter to his wife two weeks before his death at the second Battle of Bull Run. Ungar’s resonant fiddle is about all anyone can remember of his original version, so powerful was it, but in the reverent pace of this version Scott’s banjo is the dominant voice, with Aubrey Haynie, of course, shadowing him with heartfelt fiddling.

In short, every song tells a story, both in Home Sweet Home and in The Beautiful Old. Musical echoes of days long past, they live in memory; and in these artists’ capable hands, you may well find yourself longing to visit the lost world the tunes evoke. Look around–who could blame you?

Video Moment of the Week

We are well aware that July 4 has come and gone, but given the music spotlighted in our Album of the Week selections we thought it highly appropriate to designate something very American as our Video Moment of the Week. Like the music contained in our two spotlight albums, this clip of the great James Cagney performing “Yankee Doodle Boy” in his Academy Award winning turn as George M. Cohan in 1942’s Yankee Doodle Dandy, never goes out of style. Cagney’s one-take tour de force here is the stuff of film legend, and rightfully so. Cohan himself seemed to acknowledge as much when he was given a private screening of Yankee Doodle Dandy as he lay dying of abdominal cancer. “Boy, what a tough act to follow!” he said when the lights came up. He passed away in his Fifth Avenue apartment in Manhattan on November 5, 1942.

As a struggling actor Cagney, then working as a doorman and bellhop at the Friar’s Club, had been turned down for a role in Cohan production, by none other than George M. himself. When, several years hence, he was approached about portraying Cohan on screen, Cagney was well established as one of the silver screen’s reigning (and most savage) tough guys for his roles in Public Enemy, G Men, The Roaring Twenties and Angels With Dirty Faces (which earned him his first Academy Award nomination) but his skills as a singer and dancer had rarely been displayed on screen, and never memorably. Cohan himself approved Cagney’s casting after being assured Cagney could sing and dance no better than the man he would be portraying. Cagney made an intensive study of Cohan’s life and rewrote parts of the script to reflect his interpretation of certain events in the timeline, and later admitted that little of the real Cohan personality appears in the finished film. He did, however, scrutinize Cohan’s only appearance in a sound film, in 1932’s Norman Taurog-directed The Phantom President (with music by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, and co-starring Jimmy Durante and Claudette Colbert), and from it developed the stiff-legged dancing style he deploys in the “Yankee Doodle Boy” scene. Here’s a clip of Cohan (alas, in blackface for his first sketch) and Durante in a priceless moment from The Phantom President—note Cohan’s fleeting reference to his classic patriotic song “You’re a Grand Old Flag” in the opening sequence.