As a memory, it never loses its freshness, remains as vivid decades hence as on the day it happened. It was in the fall of 1978, and it started with a phone call I received while working my usual day job as an assistant editor at the music industry trade publication Record World, a younger, livelier (and alas, now defunct) competitor to Billboard. In fact, as I write this I recall it came on a Tuesday, when I was in the midst of assembling what we called The Retail Report, a weekly listing of the top selling albums at the leading chain and independent record shops (remember them?) across the country. The call was from my friend and mentor Doc Pomus, one of the great songwriters of the 20th century who had penned hits (most with his partner Mort Shuman) for Elvis, Ray Charles, Dion & the Belmonts, The Mystics, The Drifters and was less than two years away, at that time, of having his collaboration with Willy Deville, Le Chat Bleu, widely hailed as one of 1980’s best albums (and one of the best ‘80s albums when critics were polled at the end of the decade). Doc called regularly for a variety of reasons, one of the most common being to invite me to join him at the Lone Star Café, what we would now call a “roots” club on lower Fifth Avenue that specialized in country and blues. “There’s a band coming in from Austin I want you to hear,” Doc told me. “The gal singer is something special, and the guitar player’s pretty good too.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NU0MF8pwktg

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble, live at Montreux, 1985, ‘Pride and Joy’

The band was called Double Trouble, the gal singer was Lou Ann Barton, who was something special, and the “pretty good” guitarist was Stevie Ray Vaughan. They were so good I’m a bit fuzzy on who the headliner was that night, but I believe it was another blues-oriented Texas singer, Roy Head, who was terrific, as I recall, but overshadowed on that night by his opening act. (Head, a dynamic performer, had one smash hit to his credit, 1965’s “Treat Her Right,” a great rock ‘n’ roll single with a blues touch, but he was never able to duplicate its success. Which has never stopped him from making music and playing live, to this day. A real trouper, Roy Head.) Barton, not yet in thrall to the demons (mostly alcohol) that would derail her promising career, was indeed “something special,” singing blues and hard country, and commanding the stage, with authority. Before she came on, though, her band did a short opening set of 15 or 20 minutes’ duration, and after Stevie Ray’s breathtaking, even stunning, display of guitar mastery–in which he built his own thing on a foundation comprised of intimations of T-Bone Walker, Albert King, Hubert Sumlin, B.B. King, Lonnie Mack, Buddy Guy, Albert Collins, Elmore James and Jimi Hendrix–and a deeply soulful vocal style with an intriguing hint of a cry in its upper range tone and a controlled volatility more common to someone much older and more roiled by troubled waters than Stevie was then. In short, at either 24 or 25 years old, he was singing and playing like a man whose life had been well seasoned by experience (as it had–he dropped out of high school at 17 to begin his professional career playing the Austin clubs with various bands; he was living in an adult world starting in his late teens). It was a startling set, and everyone at the Lone Star knew they’d seen something different. It took Lou Ann a couple, three songs into her set to get the audience’s attention back. After the show, Stevie did what many artists did at the Lone Star, and that was to visit Doc’s table and pay his respects to the legendary songwriter. Humble and deferential, Stevie accepted Doc’s compliments with grace, then got back to the work of packing up for the tour’s next date.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3IIg_pX9j9U

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble, the pivotal Montreux Jazz Festival performance from 1982. From the DVD Live at Montreux 1982. A 10-and-a-half minute version of ‘Texas Flood.’

This is what I remember of Doc Pomus’s reaction to what we saw that night at the Lone Star: “Lou Ann ought to be a star,” he said, “but Stevie will be a star.” My review of the show in Record World was apparently the first national press SRV ever received but I certainly did not predict for Stevie anything of the magnitude of what happened with the release of his first album, Texas Flood, in 1983. But Doc saw him coming from the first, even as he foresaw Lou Ann’s self-destruction.

The Lone Star turned out to be the last for Double Trouble with Lou Ann Barton. She split and wound up with the Fabulous Thunderbirds next (and married the band’s troubled bass player, Keith Ferguson, who eventually died of a drug overdose), Stevie took the Double Trouble name and bassist Chris Layton, added Tommy Shannon on drums after Jackie Newhouse left, and began the work of establishing himself as a solo artist. In 1982 legendary producer Jerry Wexler (who had just co-produced, with Glenn Frey, Lou Ann Barton’s solo debut, Old Enough, for Elektra Records) heard Double Trouble and leaned on his friend Claude Nobs, head of the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland, to book Double Trouble. The band’s performance caught the attention of David Bowie, who would hire Stevie to play on his Let’s Dance album, and agree to let Double Trouble play an opening set on the subsequent tour in support of the album. (Bowie, who had to wear a dress to get signed, reneged on his promise, and a fed-up SRV gathered up Double Trouble and went home.) More crucially, Jackson Browne became a huge Double Trouble fan after catching the band at an after-hours jam in Montreux, so much so that he offered them the use of his L.A. studio–a glorified name for a warehouse stocked with home recording gear–whenever they decided to record themselves. Around Thanksgiving of ’82 the band packed its gear into a van and headed west for what turned out to be three days of sessions (one full day devoted to setting up), recording what was essentially Double Trouble’s live set in what can only be described as a “live” setting.

From Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble’s Texas Flood debut, the SRV original instrumental, ‘Lenny’

The album’s original muddy sound worked in the band’s favor in enhancing the sense of the recording being recorded live in some joint, which Jackson Browne’s warehouse studio might well have been. Its songs pay home to the wide range of influences SRV had absorbed, sometimes subtly (the breakneck boogie “Rude Mood” quotes liberally from Lightnin’ Hopkins’ style, but the licks speed by so fast you might miss them in the ensuing fury), sometimes overtly (the shimmering, robust notes and languid, tender feel of “Lenny,” an instrumental Stevie wrote for his wife, seem like a nod to the lovely George Harrison lead on The Beatles’ “Sun King,” from Abbey Road). Bluesman Larry Davis wrote and recorded “Texas Flood,” a grinding 12-bar blues lamenting a relationship gone sour, in 1958 for Duke Records. Stevie’s vocal is admirably wounded and even assertive at points, when he’s announcing he’s “going back home to stay,” but he expands Davis’s original to include a couple of extended, stinging 12-bar solos that cut like Albert King at his most aggrieved. Another mean woman blues from the past, Howlin’ Wolf’s “Tell Me,” recorded in 1957 and released on Wolf’s self-titled 1959 Chess album, energizes the original slow rockin’ pace with an intense, driving tempo, and where Wolf embellishes his growling vocal with wailing harp solos, Stevie cuts loose with a precision flurry of ostinato riffing, single string wails and heated frailing; vocally, his thick, throaty delivery brings to mind no one so much as Gregg Allman, an impression deepened by the stop-time ending followed by a decisive vocal postscript–“can’t be where it’s at no more” (peculiar to SRV’s version)–similar to Gregg’s “might be your man, I don’t know” postscript following a final stop-time pause on “One Way Out.” “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” from Buddy Guy’s 1967 album Man and the Blues, finds Stevie adopting a breathy, conspiratorial tone vocally in interpreting Guy’s somewhat naughty take on the nursery rhyme (suggesting Mary was engaged in salacious conduct at school, for instance), but the real story of the largely instrumental track is SRV’s clean, heated picking and absolute mastery of one of Guy’s signature licks, which involves playing a bass run immediately followed by a rhythm lick, which requires silencing the top E and playing the rhythm without missing a beat, and then moving on to the cool fill. Although the Chuck Berry-styled romp “Love Struck Baby” and the seismic stomp of “Pride and Joy” are among the fans’ best-loved SRV tracks, the bottomless depth of his “Dirty Pool” may have best served notice of the magnitude of artist he would become. Its doom-laden atmosphere and Stevie’s wrenching, unusually textured vocal–a mix of upper register cries and lower register rumbles–are one thing; the incredible guitar soloing quite another. For most of the song Stevie sustains a steady, shredding attack with spikes of searing single notes and single-string runs here and there to enhance the song’s malevolence.

From Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble’s Texas Flood debut, a cover of Howlin’ Wolf’s ‘Tell Me’

The completed album wound up in the hands of the towering producer John Hammond, who was no longer at Columbia Records (where he had signed everyone from Billie Holiday to Bob Dylan to Bruce Springsteen, et al.) but had his own production company and was still quite active in the business. Before leaving Columbia, he had become mentor to Gregg Geller, who, as he says himself, became “Mr. New Wave” at the label, with Elvis Costello being one of his notable signings. He would go on to inaugurate quality reissues programs at RCA and at CBS, including the repackaging and general straightening out of Elvis Presley’s catalogue. Hammond brought the SRV to Geller. In a February 2011 interview with TheBluegrassSpecial.com upon the Geller-produced reissue of Stevie’s second album, Couldn’t Stand the Weather, he recalled the moment he first heard Stevie Ray Vaughn and Double Trouble:

“In 1983 John showed up with this Stevie Ray Vaughan album and I flipped. If you recall the kind of music that was happening at the time, some of which I was involved in–I was ‘Mr. New Wave,’ you know–but my personal tastes run to rockabilly and blues. The first thing I heard was “Love Struck Baby.” It was like a bolt out of the blue. I have this theory, the ‘gap’ theory, which is that there are certain kinds of music for which there is always an audience. And occasionally the market doesn’t satisfy that audience. There’s a gap where that audience isn’t being supplied with what it wants to hear. To me that always explained the success of the first America album–everybody wanted another Neil Young album, so they got their fake Neil Young album. But Stevie obviously was no fake, but there was nobody doing what he was doing–you know, Eric Clapton was making pop records. There was just nothing like it at the time. I figured all those folks out there that like great guitar, how could they resist?

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble, ‘Love Struck Baby,’ live in New Orleans, 1987

“I always stress this. As great as the guitar was–undeniably great–what struck me was how well he sang. If you think about all the white blues guitar players, from Johnny Winter to all those guys out of England, to me the vocals always rang false. It always sounded like they were trying to sound black. Stevie just sounded like himself, totally natural. That’s what really did it for me. That’s why I felt so confident about the record. That to me placed him head and shoulders above the competition–(laughs) of which there really was none.”

Thirty years ago this month, on June 13, 1983, Texas Flood was released on Epic Records. Possibly the unlikeliest hit of the synth-pop era, it was eventually certified double platinum, denoting sales of 500,000 units. Epic/Legacy is marking the 30th anniversary with a double-CD release of Texas Flood plus a previously unissued live recording from Philadelphia’s Ripley’s Music Hall, on October 20, 1983, that emphasizes the fiery side of SRV and Double Trouble–close to what I had heard at the Lone Star Café back in ’78. Two terrific Hendrix covers are featured–“Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” and “Little Wing/Third Stone from the Sun”–plus several key tracks from the first album: “Texas Flood,” “Pride and Joy,” “Love Struck Baby,” a furious cover of the Isleys’ “Testify,” “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” It also includes “Tin Pan Alley (aka The Roughest Place in Town),” a tune recorded but left off Texas Flood, and “So Excited,” a blistering instrumental that not only demonstrates Stevie’s mastery of tone, texture and dynamics, but also underscores how solid a rhythm section he had in Shannon and Layton, whose contributions to the SRV legend are too often overlooked. That the power trio lineup worked as well as it did was due to more than the guitarist’s transcendence–he had a formidable, sensitive rhythm section at hand and, later, when Reese Wynans joined the band on keyboards, an even richer, more evocative live and studio sound.

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble cover Hendrix’s ‘Voodoo Child’ at Volunteer Jam XIII, 1987

Doc Pomus, who was an outstanding blues singer before he gave up performing and recording to concentrate on songwriting, couldn’t have been happier to see the blues artist he predicted would be a star kicking ass and taking names on the pop charts when Texas Flood broke out in ’83. By that time I was at Rolling Stone, and when I answered a call one day along about August, there was Doc on the other end of the line chuckling over SRV’s success. “How about that?” he asked joyously. “How about that?”

Listen anew to Texas Flood, and you’ll be saying the same thing.

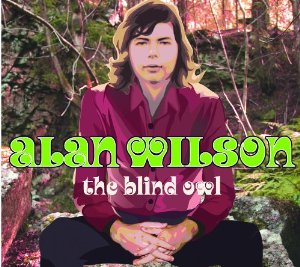

Not that anything lessens the tragedy of Stevie’s death in a helicopter crash in August 1990, but at least he had survived drug addiction, successfully rehabbed and came through it with a powerful final studio album, In Step, that suggested more glories lay ahead. When Alan Wilson of Canned Heat died of an apparent drug overdose at age 27, on September 3, 1970, his passing was noted in a few music magazines and he quickly receded into history, his work treasured by hard-core blues aficionados, blues guitar freaks, baby boomers, perhaps, and that’s about it.

Clinically depressed, Alan Wilson was a brilliant, troubled and utterly distinctive blues man with a fragile, sensitive psyche who attempted suicide three times. Long before the environmental movement was much of a movement and anyone had heard of global warming, he was frightfully worried about the planet’s deteriorating ecological state–he and his manager Skip Taylor, through their Music Mountain Foundation, led an early effort save ancient redwoods in northern California, which still stand today. On Canned Heat’s Future Blues album, which showed an upside down American flag on its cover, with a smog-covered earth in the background. “It was our way of saying we were worried that some day humans might pollute the moon,” Taylor says. That album, the last to feature Wilson as well as original members Larry Taylor and Harvey Mandel (who left Canned Heat shortly after the album’s release), features a cover of Wilbert Harrison’s plea for unity, “Let’s Work Together,” “So Sad (The World’s in a Tangle),” “Future Blues” and the tragically prophetic Wilson original, “My Time Ain’t Long.” He was self-conscious about his looks, and he so nearsighted he was all but legally blind, hence his nickname “Blind Owl” (bestowed by Wilson’s friend John Fahey, whom Wilson accompanied to UCLA for the express purpose of helping Fahey complete his master thesis on mythology and folklore–Fahey later said Wilson “taught me enough about music theory to write his master thesis on Charlie Patton.”) Lacking much self-confidence and lugging a boatload of self-consciousness about his appearance (in some Canned Heat photographs his pants are hiked up almost as high as those of Martin Short’s Ed Grimley), Wilson didn’t have bad luck with women–he had no luck. As Taylor reveals in his liner notes to The Blind Owl: “Even when Canned Heat was one of the hottest acts in the world, he found himself unable to bed otherwise star-obsessed groupies. Alan failed at finding a relationship with any gal. He definitely talked about it and was emotionally scarred by it. We all tried to help, but I’m not positive he ever slept with a woman. He had trouble relating to the world and people in general…just listen to his lyrics.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DRU8fRWR8ik

Canned Heat at Woodstock, ‘On the Road Again.’ Bob Hite plays the live harmonica solo; Wilson played harp on the record in what was ‘one of the first recorded examples of a custom-tuned diatonic.’

On the other hand, he was such a student of early blues that he was hired by Dick Waterman to re-teach an aging and alcohol-impaired Son House, whom Waterman had tracked down in 1964, the licks and lyrics to songs Son had recorded in 1939 and 1942. Son subsequently enjoyed a 10-year revival of his music career, during which he was enthusiastically received by a younger generation rediscovering acoustic blues. Son and Blind Owl often performed together, and cut an album as a duo, John the Revelator: The 1970 London Sessions. A music major at Boston University, rather than partying he preferred staying in and studying old 78s and reading whatever he could find about early American music. He wrote definitive articles about Son House and Robert Pete Williams. When Canned Heat made its great album with John Lee Hooker, Hooker ‘n Heat, the legendarily prickly bluesman, who was difficult to accompany because of his fleeting relationship to time signatures, could hardly find compliments enough for Wilson. “Alan plays my music better than I knows it myself,” he said. “You musta been listenin’ to my records all your life.” Hooker also called Wilson “the best harmonica player ever.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Luq3g47cbWI

Canned Heat at Woodstock, ‘Going Up the Country,’ lead vocal, Alan Wilson

Then there was Canned Heat, the band the Boston-born Wilson and native Californian Bob “Bear” Hite formed in Los Angeles in 1965, with an imposing lineup that also included Henry Vestine (and come mid-1969, Harvey Mandel, stepping after Vestine quit) on lead guitar, and an awesome rhythm section of Larry Taylor on bass and Adolfo “Fito” de la Parra on drums. These young men were all students of the blues, proselytizers for the blues, and gifted players to boot. After the band’s well-received appearances at 1967’s Monterey Pop Festival and two years later at Woodstock (which found their song “Going Up the Country”–Wilson’s rewrite, with a back-to-nature theme, of Henry Thomas’s “Bulldoze Blues”–becoming the festival’s unofficial theme song after it was prominently featured in the festival movie), Canned Heat vaulted out of the blues niche into pop stardom. Without underestimating the contributions of his bandmates, Wilson’s vision, singing, instrumental and songwriting skills separated the quintet from all its competitors. Of these, the most distinctive, if it’s possible to isolate one from the other, were his singing and his harmonica playing. As a vocalist, he seemed to have emerged from the dark heart of the Mississippi Delta, down Bentonia way, with an eerie, aching, high-pitched moan and wail of a voice, as if he were channeling both Skip James and Jack Owens all at once. Next to Frankie Valli’s soaring falsetto, it may well have been the era’s most unusual voice. That’s him on “Going Up the Country,” on “On the Road Again,” and in fact on every song on Severn Records’ vital two-CD collection The Blind Owl, a long-awaited and richly deserved tribute to a great artist’s legacy.

Alan Wilson, ‘Sloppy Drunk,’ a rendition of Leroy Carr’s ‘Sloppy Drunk Blues’ (unreleased recording)

Apart from the spacey, sitar-sounding intro and heralding chimes introducing “On the Road Again,” the most striking effect is the entrance of Wilson’s harmonica, shimmering, deep, rich, and different, as it always was, before Wilson enters singing lyrics so much more troubling in light of the details of his inner life that emerged after his passing: Well, I’m so tired of crying, but I’m out on the road again/Well, I’m so tired of crying, but I’m out on the road again/I ain’t got no woman just to call my special friend. No, he never did. But in his professional life he was a master of many things including what is known as the “overbend” technique. As defined by The Harp Reference, “a so-called overbend is a type of bend where the pitch that results is higher in pitch than the natural note of either reed in the hole, rather than lowering the pitch as with ordinary bends. This is because the overbend technique actually causes the normally sounding reed to choke while you’re playing so it doesn’t sound, and causes the other reed in the chamber to sound as an opening note instead.” That is to say, you actually take apart the harmonica and alter the reeds with a metal file so you can blow harder and hit certain lower and higher notes that you wouldn’t otherwise be able to hit.

Alan Wilson (aka Blind Owl Wilson), ‘Blind Melon’ (unreleased home recording)

In fact, Wilson’s technique on the harp is the subject of a learned discourse at patmission.com, in response to the question, “How did Alan Wilson play the solo on ‘On the Road’?” Check this out:

In the middle of a typically lyrical solo on Canned Heat’s “On The Road Again,” Al Wilson hits a G in the midrange of his A harmonica. A standard diatonic in the key of A has a G#, but no G built into it. It is not possible to bend the G# in this octave, so how did he do it?

Several suggestions have been put forward. Perhaps he played an overblow? That is possible as other players around that time were starting to discover overblows and the hole 6 overblow on an A harp would give you a G. However, the slide down from this note includes a very quick slur over the D (5 draw) and the B (4 draw). If he had to switch between an overblowing and drawing, there would be a slight hiccup in this phrase. Several people who knew Al Wilson said that he would sometimes weight the tip of the 7 draw reed to lower its pitch by a semitone, however if this were the case, then that slide down would include an F# (6 draw) and listening to it at slow speed indicates there is no discrete F# note present. Another explanation has been given that he added a valve to the outside of the 7 blow reed, enabling him to bend the 7 draw down to a G–this would also mean that a slide down from this note would include a discrete F#.

Alan Wilson, ‘Blind Owl Piano Blues’ (unreleased home recording)

The explanation is that he retuned the 6 draw reed, raising it by a semitone to give him the G. This is consistent with the notes of the slide down from that note, as you can hear on this slowed down clip:

Wilson is playing the retuned 6 draw to give a G, which he then bends down to a rather flat F#, followed by the D (5 draw) and the B (4 draw). He used a similar tuning on other tunes, such as “TV Mama” and “Nine Below Zero.

So, one of the biggest pop hits to feature blues harp, is also one of the first recorded examples of a custom-tuned diatonic.

Alan Wilson, ‘Death Bed Blues’ (unreleased home recording of a song recorded by Canned Heat and released on 1969-1999: The Boogie House Tapes Volume Two)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IqbpgM51wwE

Canned Heat, ‘Human Condition,’ recorded July 30, 1970, the last studio recording with Alan Wilson on vocals and guitar; included on The Blind Owl retrospective. It was completed after his first suicide attempt when he drove his van off the road.

“Alan Wilson was a conscience-genius of the blues,” notes guitarist Kyle Fosburgh, himself a student of American roots music. “He was authentic in his style, adapting the old patterns and runs for a modern band.” The corrective that is The Blind Owl should convince anyone of the truth of Fosburgh’s assertion. It’s not about rare tracks–the discs are comprised of songs off various Canned Heat albums–but rather about an unwavering spotlight on Wilson’s most important contributions to the band. The liner notes by Skip Taylor (who found Wilson dead in a sleeping bag behind Bob Hite’s house, with an empty bottle of gin and an open bottle of Seconal on the ground beside him) and blues collector Michael Leddy are informative and touching.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2yjF7rF0YBA

Canned Heat, live on Playboy After Dark, 1969, ‘My Time Ain’t Long,’ from the album Future Blues. Al Wilson on rhythm guitar and lead vocal.

What if Stevie Ray hadn’t got on that helicopter? What if Alan Wilson had been able to get the help he needed? Questions with no answers, forever lingering. But with this music, these artists still reach out to us. Feel their embrace, and cherish what we had when we had it.

FYI: This past March saw the publication of a full-scale biography of Alan Wilson, Blind Owl Blues: The Mysterious Life and Death of Blues Legend Alan Wilson. Author Rebecca Davis offers a wealth of inside information and insight, including the intriguing theory that Wilson may have suffered from undiagnosed Asperger Syndrome. .