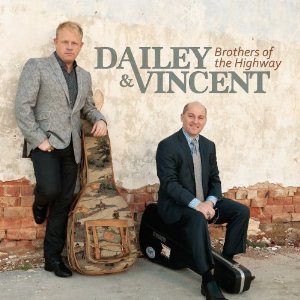

BROTHERS OF THE HIGHWAY

Dailey & Vincent

Rounder Records

No beating around the bush here: when Jamie Dailey and Darrin Vincent return from their travels through the worlds of gospel (2012’s The Gospel Side of Dailey & Vincent) and the Statler Brothers (2010’s Dailey & Vincent Sing the Statler Brothers) and deliver a dozen solid traditional-styled gems of the sort that made them bluegrass superstars out of the box with their eponymous 2008 debut, well, it’s a big deal. Not that the duo was slumming on the aforementioned long players: The Gospel Side of Dailey & Vincent is a powerful, moving testimony of faith and impressive enough to rank as #18 in this publication’s Elite Half Hundred of 2012, a best-of ranking that includes albums from all the roots genre’s Deep Roots covers, including classical; and reminding listeners of the great songs the Statler Brothers (a profound influence on Dailey in particular) left us upon their retirement seems a noble undertaking, regardless of its commercial viability.

In a real sense, Brothers of the Highway is as much a concept album as the two preceding it. It may seem a disparate bunch of songs–a couple of strong Dailey originals mixed in with tunes from Bill Monroe, Wilma Lee Cooper, Vince Gill, the Louvins, Pete Goble and others–but in fact D&V might well have titled their new album The L Word–not, mind you, in referenced to the cable series centered on lesbian life, but rather for the album’s multiple themes of Living, Lovin’, Losin’ and Leavin’.

Dailey & Vincent perform Ira and Charlie Louvin’s ‘When I Stop Dreaming,’ from Brothers of the Highway.

Livin’, of course, might cover every song on here, since by definition it incorporates Lovin’, Losin’ and Leavin’, but for rhetorical purposes let’s say this theme is best represented by the spirited “Howdy Neighbor Howdy,” heretofore known as one of Porter Wagoner’s classic fellowship songs in the spirit of his “Company’s Comin’.” D&V’s version diverges from Porter’s in expressing the pleasant surprise of an unexpected visit whereas Porter’s was practically giddy in its elation over same–an emotion Wagonmaster banjo giant Buck Trent gave full reign to in his audacious, driving solos on an electric banjo sporting a wooden head, four Scruggs tuners and two push buttons near the bridge that activated a pedal steel changer he had devised several years before Clarence White introduced the B-Bender. What we do get here are amiable vocals by D&V and, supplanting the Buck Trent solos and the equally fervent fiddle solo by Wagonmaster virtuoso Mack Magaha (who, incredibly, could also dance an Irish jig while he fashioned the most furious fiddling you ever heard), a buoyant banjo-fiddle dialogue between Jesse Baker (banjo) and the twin fiddlers B.J. and Molly Cherryholmes keying a delightful interpolation of “Turkey in the Straw” about three-quarters of the way through.

Vince Gill sits in with Dailey and Vincent on his song ‘Hills of Caroline,’ which D&V cover on their Brothers of the Highway album.

Lovin’ and Losin’ go hand-in-hand in this context, and what a beautiful sadness they create. Dailey and Vincent’s keening harmonies on the Louvins’ “When I Stop Dreaming” are replete with epic heartbreak and haunting tenderness (Vincent takes the Charlie Louvin lead part; Dailey, whose high tenor is a natural wonder, ably steps into Ira Louvin’s high tenor spot; their singing is so entrancing and nuanced you might have a hard time remembering they are supplied with beautiful, understated instrumental support from Jeff Parker on mandolin, Andy Leftwich on fiddle and Johnny Beller on dobro, so keen are the musicians on conjuring the appropriate forlorn ambiance while remaining a discrete element of the soundscape). In one fell swoop Wilma Lee Cooper’s “Tomorrow I’ll Be Gone” hits the big trifecta of Lovin’, Losing’ and Leavin’; the pace is sprightly, the fiddling (by Andy Leftwich) spirited, and the lively lead vocal, by Dailey, awash in schadenfreude over his faithless lover finding herself the victim of her new man’s duplicity. “Close By,” Bill Monroe’s howl of loneliness emitted years after a heart wrenching breakup, inspires in Dailey a masterful vocal performance in which he toggles between being bereft over losing the love of his life and finding comfort in hearing she died some time back and “your soul will live forever and I know you’ll be close by.” Now he’s looking to be buried next to her in the same cemetery so they’ll be “close by” through eternity. That’s some country grammar right there, Nelly, and banjo man Joe Dean and Aubrey Haynie, doubling himself on fiddle, emphasize this splintered logic in their solos, Dean’s being steady and subdued, Haynie’s soaring and exultant.

Dailey & Vincent, ‘Steel Drivin’ Man,’ the opening track, written by Jamie Dailey, from Brothers of the Highway

The Leavin’ part might also be considered “coming back,” in that no less than three tunes anticipate the singer’s return to or fond recollections of old stomping grounds, where his most cherished childhood memories reside: one of these is Dailey’s high-stepping “Back to Jackson County,” a banjo- and fiddle-fired workout featuring a cheery Dailey vocal in which he sounds as if he’s not merely singing lyrics but speaking from bone-deep conviction (Jeff Parker jumps out of the frolicking arrangement with a dazzling, rapid-fire mandolin solo that fiddler B.J. Cherryholmes seconds when his turn comes around); a toe-tapping, evocatively harmonized rendition of Pete Goble’s “Back to Hancock County” is a true Leavin’ song on the one hand, in which the lyrics reflect on the simple pleasures of a small rural community the singers remember from their youths, and on the other a commitment on their part to return and try to recapture something they lost in the leavin’ part; one of the most touching moments on any D&V record comes via a spare, haunting exploration of the sweet melancholy infusing Vince Gill’s “Hills of Caroline,” with only Vincent’s acoustic guitar and Bryan Sutton’s archtop (along with Vincent’s harmony singing) supporting Dailey’s heartfelt, deeply aching reflections–the slight elevation in his voice when he and Vincent harmonize on the title phrase bespeaks a profound sense of loss–on the roots of his raising, about people and a place he left behind but which remain an ever-vivid presence in his life

Dailey & Vincent: A teaser video for the duo’s interpretation of ‘Where Have You Been,’ a cover of the Kathy Mattea classic D&V cover on Brothers of the Highway

This song mix also encompasses Dailey’s other original contribution, the hard driving album opener, “Steel Drivin’ Man,” about the punishing life of an indefatigable working man (who is not John Henry, by the way) and an impressive showcase for breathtaking, blistering solo runs by Jessie Baker, Andy Leftwich, Bryan Sutton and Jeff Parker in a tune that may remind some listeners of the Del McCoury Band’s interpretation of Richard Thompson’s “1952 Vincent Black Lightning.” The fellows nod to their gospel roots, too, of course, with a rich bluegrass gospel treatment in four-part harmony on “Won’t It Be Wonderful There.” Given all the Lovin’, Leavin’ and Losin’ going on here, though, what a brilliant stroke to close the album by reminding us about the Livin’ with a string-enhanced take on Kathy Mattea’s classic ballad, “Where Have You Been” (co–written by her then-husband, Jon Vezner), with Dailey bringing the full weight of his interpretive skill to the story of an elderly couple’s final reunion as their lives ebb away in separate rooms of a hospital. You can’t listen to this without, at once, reflecting on your own life and seeing mature love in a different light, which was one of the great accomplishments of Ms. Mattea’s version. It’s the perfect finale to Brothers of the Highway: Love persists is the message, and no more important L word exists in the known universe.