Molina made music that mattered, less because it was so obviously born of his inner quaking than that in the midst of its winsome musings arose a scintilla of hope, a sense of things maybe, maybe, working out for the better.

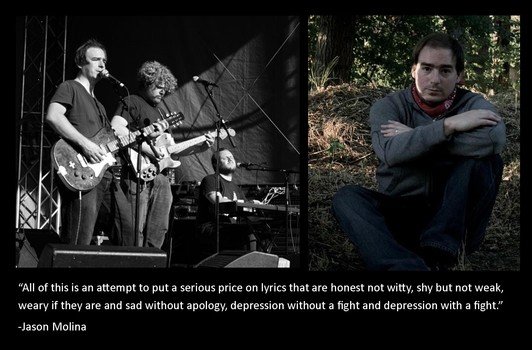

Singer-songwriter Jason Molina died at age 39 on March 16 from what was reported to be “alcohol abuse-related organ failure.” Never a household name, Molina was steadily–or seemed to be–gaining traction with his beautifully crafted, sensitive and sometimes painfully raw folk- and country-influenced songs (the spirit of Gram Parsons is knocking around in gems such as “Just Be Simple”). Though he was forever struggling with the debilitating effects his alcohol addiction wreaked on his personal and professional lives, Molina never retreated as an artist, despite the last few years of his life being clearly torturous. He visited various rehab facilities and even took a job working on a farm in West Virginia raising goats and chickens while also “looking forward to making great music again,” according to a note from his family posted on the website of Secretly Canadian Records, Molina’s professional home.

But the music he made while he was here deeply affected those who heard it. If he didn’t qualify as a cult figure in life, he’s likely to become one in death, because his music, and the tragedy of his early demise–he was only 39–will endure as legend. Or perhaps as another cautionary tale. Much like Scott Miller, so evocatively conjured by contributing editor Christopher Hill elsewhere in this issue, Molina made music that mattered, less because it was so obviously born of his inner quaking than that in the midst of its winsome musings arose a scintilla of hope, a sense of things maybe, maybe, working out for the better. A YouTube clip from 2002 is arresting, not only for the smoldering, deliberate—and wobbly—rendering of “Division St. Girl,” from his Songs: Ohia incarnation, but for what he says to the audience at The Earl in Atlanta before he plays. Turning suddenly melancholy after some cheery business trying to lure a cornet player onstage, Molina says softly: “I don’t know what’s gonna happen. But listen. Don’t listen to me. Just listen. You gotta take care of each other. You know what I’m sayin’? Take it nice and slow.” You heard this kind of talk from artists in the ‘60s, when we all believed we were one big community and could change the world—hell, Grace Slick even uttered similar words from the stage at Altamont as, before her very eyes, Hell’s Angels beat the bloody bejesus out of anyone who looked at them sideways. But Molina wasn’t speaking in the ‘60s, and the idealism and the spiritual resonance of his words in 2002 is both touching and chilling, precisely because he seemed to be talking to himself as much as to the audience, delivering at once admonition and premonition. No wonder the deeply emotional responses news of his death generated all over the Internet on and since the day the tragic news was first reported.

Andrew Gilstrap, writing in Pop Matters on April 10 had this to say, in part:

At the time I’m writing this, it’s been roughly a week since Jason Molina died. In that time, I’ve been doing what most Molina fans have been doing: driving around with a stack of Songs: Ohia and Magnolia Electric Co. CDs beside me, keeping me company on drives that are last a take a little longer, go a little farther than they need to, reading interviews, watching YouTube videos of live shows, listening to an online stream of everything Molina ever recorded, or watching things like this fantastic documentary about the making of the Josephine album.

As far as writing about his death, that wasn’t something I relished doing. For one, it takes you away from immersing yourself in his work. Granted, listening to Molina’s records reminds you that he’s gone, but it at least does so by wrapping you in the beauty of his songs. To turn the music off, though, to leave the comfort of those songs and attempt to actually describe the ineffable quality that made his songs so special? That’s like trying to catch one of the will-o-the-wisps he liked to sing about.

…

Molina’s language of symbolism was heavy with ghosts, falling stars, highways, birds, flowers, maps, and broken hearts. His tendency to mine the same imagery throughout his career always made it seem like the perfect Molina song was just a matter of the right symbols landing together at the right time. Arguably, he never came closer than 2003’s Magnolia Electric Co. album, which found Molina making the shift from his Songs: Ohia incarnation to the MEC framework that would serve his songs so well. “Farewell Transmission”, “Riding with the Ghost”, “Just Be Simple”, “Almost Was Good Enough”—that’s an album-opening murderers’ row that stands up against any four songs by just about anyone.

Jason Molina, ‘Don’t This Look Like the Dark,’ at the Motel Mozaique, Rotterdam, 2003

Jason Molina, ‘What Comes After the Blues?’ Live at ACME Comics, Columbia, SC, September 3, 2006

When I got the news that Molina was dead at the age of 39, I cursed. Then I thought to myself, “This must be what it felt like to folks when Townes Van Zandt died.” That’s not to compare the two in terms of talent. I’m not about to stand up on Steve Earle’s coffee table and preach that one was better than the other. In fact, I’m not sure how much that comparison holds water, anyway.

True, the circumstances of their deaths—their bodies, ravaged by alcoholism, finally gave out—link the two in a long chain of singer-songwriters whose addictions brought them down. However, I think they approached sadness in different ways. They could both break your heart, but they seemed to striving for different goals. Van Zandt was fully capable of applying beauty to tales of dying prostitutes, life on the road, or sickness, but he was also prone to following that sadness to the back of whatever cave it lived in, not bothering to light a lamp so he could find his way back out. What’s always been surprising about Van Zandt were his claims that he wrote plenty of songs that he called his “3 a.m. blues,” which were too sad or dark to ever be recorded or released.

With Molina, the sadness was linked to the struggle of getting through the day, getting to the next day, living up to the belief that you saw in your partner’s eyes. Molina’s songs could be dark—for God’s sake, “Farewell Transmission” boasts the line “Mama, here comes midnight with the dead moon in its jaws”–but that darkness wasn’t the destination. It was a place from which you wanted to escape, and a reference point for what was to come if you got out. It was the pain and baggage and regret that made the quiet and hope and love emerge that much more strongly.

Jason Molina as Magnolia Electric Co., ‘Just Be Simple’

In his Songs: Ohia incarnation, Jason Molina performs ‘Blue Factory Flame’ at Bloomington Fest 2000, in the Cellar Lounge, Bloomington IN

And this, from Drew Litowitz (headlined “Jason Molina: Fading Trails”) in Consequence of Sound, on March 25:

On the one hand, the pure love expressed for Molina–from Steve Albini, to Jens Lekman, to Will Johnson, to artist Will Schaff, to Strand of Oaks’ Tim Showalter, to countless others–has been comforting in the sense that so many have been affected by just one man’s songs. It has become clear in the last seven days, that his seemingly little-known music was cherished by a small few for its honesty, craftsmanship, and beauty. Personally, I never knew how many people felt the same as me. In death, it is plain to see that he was well loved by all sorts of people. His friends and family cherished him. His fans clung to his songs. He will be missed.

But this flood of sadness and regret also makes his early death all the more difficult to bear. In the end, after the PayPal medical funds, the cancelled tours, and the personal desperation, no amount of distanced love could save Molina from the very ghosts he sang to. For a man whose art bled with sadness and despair, it should come as no surprise that those ghosts eventually got the better of him. The songs were so sure of themselves, though, that things always appeared under control.

…

As a mere listener of his records, I can’t speak to Molina’s personality, demeanor, or even his stage banter. Instead, I speak strictly as somebody who has been slowly making his way through his daunting, glorious discography for the past half-decade. What I can say is that Jason Molina’s music has been a source of much comfort and hope for me for the past few years. Molina’s desperate, self-aware musings on conflicted relationships, depression, dark lonely nights, spirits, lunar luminosity, and American geography, have become beacons of hope in a strange way. Something about Molina’s brooding folk-rock brought with it a sense of hope. Wherever he went, as dark as the night got, he always had the North Star and the moon to guide him. He always had a trail ahead of him. He developed his own language of moons, ghosts, animals, and shadows. We followed along. He persevered through song.

…

Just as Molina saw the moon as a constant source of light, his ability to distill his own despair into pure, well-constructed, honest songs, helped put things into perspective for those of us listening. If he could do it, so could we.

Now that he’s gone, it’s hard to know what to make of all of this. The fact that the demons won in the end is troubling. It threatens to undercut all the hope and solace his music offered. What I do know is that Molina tried his very best to figure things out. His songs will forever stand as proof of that, reminding us all that for every dark, lonely night, there’s always the moon’s hazy glow. What we do with that glow, or how we respond to it, is up to us. And we must simply try our very best.

Jason Molina, ‘Division St. Girl,’ August 3, 2002 at The Earl in Atlanta

On the other side of the coin, there were thoughtless, ill-considered pieces as well. In The New Yorker of March 19, Ben Greenman ponders Molina’s legacy while sitting in a bar (“I ordered a vodka…”) but fails to experience any eureka moments of insight into the artist’s work and worth; and a blogger identified only as Drug Punk, who at least admits to having a strong taste for “booze and drugs,” posits Molina’s music as the choice to turn to “when your way gets dark, your girl/boyfriend leaves you, and there’s miles to walk with only a bottle of whiskey to accompany you.” Given Molina’s long, desperate and ultimately losing battle with alcoholism, musings soaked in drink seem at the very least self serving and disrespectful, at worst shockingly insensitive.

The most important piece to be published since Molina’s passing–and the one that deserves a wider audience and a serious conversation–is by Max Blau in Stereogum, April 22. Headlined “Deconstructing: Jason Molina, Uninsured Musicians, And the Importance of Health Care,” Blau offers an informed, solidly reported perspective on the perils of the average working musician in this country–and there are far more average working musicians trying to make ends meet than there are overhyped money machine dullards such as Justin Timberlake–trying to keep body and soul together working for tips, CD sales and anything resembling a decent payday that will help keep a roof over their heads. Noting how Molina’s record label, Secretly Canadian, is releasing a tribute compilation, Weary Engine Blues, and donating 100 percent of its proceeds to the artist’s family, Blau nails the cold, hard facts of the matter:

As his friends and admirers now pay ode to the influential songwriter, it offers a reminder of how fundraising efforts–be it benefit shows or tribute compilations–fail to address the larger problem facing musicians. That’s not to say they lack good intentions. The Savannah-based label will graciously donate 100 percent of its proceeds to Molina’s family. But it doesn’t change the fact that the prolific songwriter’s death could have been prevented with access to affordable health care.

He’s hardly alone. Nearly one-third of American musicians are uninsured–double the percentage of the overall population without medical coverage. Only an estimated five percent of insured musicians, namely session musicians and orchestra players, have health care provided through their professional musical careers. That unfortunately doesn’t include most indie-rock artists.

Instead, most musicians scrape by selling records, tickets, and merchandise–all revenue sources that don’t guarantee a steady paycheck. As a result, artists often forego steep health-care costs to pay for food, rent, and other necessities. “If you’re living on 15 or 20 thousand dollars a year, then health insurance actually does become a luxury,” Health Insurance Navigation Tool program director Alex Maiolo told Indy Week in 2008. “It’s hardly a luxury. It’s something people need.”

Jason Molina in the Magnolia Electric Co., days, ‘Hold On Magnolia,’ live in Birmingham, AL

Blau document one case after another of musicians, even in well-known bands such as Grizzly Bear, enduring all sorts of debilitating maladies, many of them easily curable, for lack of affordable health care.

Solutions? A few organizations–the non-profit Future of Music Coalition and Grammy.org’s MusiCares in particular–are singled out for providing free health care or aid in some form, although Blau notes, “all too often…these options aren’t pursued.”

Looming as a beacon of hope for millions of uninsured Americans regardless of occupation is the implementation of Obamacare on January 1, 2014. Notes Blau: “Once that happens, insurers won’t be allowed to charge higher rates based on pre-existing medical conditions. It will also enable men and women to purchase insurance in health insurance exchanges soon created in each state. The same goes for the many states that will expand their Medicaid programs, which could make lower-wage workers, including musicians, eligible for the federal health plan. The U.S. healthcare system will be improved in the near future, but it won’t be fixed altogether. Some artists will still fall through the cracks as Obamacare’s policies become implemented. But for the most part, more musicians should have access to less expensive medical coverage.”

An interview with Jason Molina from Schubas.com, posted at YouTube, Part 1 (2010)

Part 2 of the Schubas.com interview with Jason Molina (2010)

“How do musicians make a living?” remains the tough question with no easy answers or options. Give up the security a 9-to-5 job might offer–assuming you can find a 9-to-5 job now–or forego decent housing and luxuries such as health care in order to live a more unfettered, unstructured life dedicated to the creative impulse? “Pursue music as an avocation instead of a vocation”? “Granted, it’s not sexy,” Blau concludes. “It’s hardly flashy. But it pays the bills–insurance included. Now would Molina still be alive if he viewed music in this regard? It’s impossible to say. But it makes you wonder.”

Jason Molina, ‘Farewell Transmission,’ Aug. 8, 2002 at The Earl in Atlanta

Blau may sound like he’s telling musicians to declare “No mas!” and get a real job, but what he’s really doing is pointing out how perilous it has become to be an artist in America, regardless of whether you’re healthy or battling demons you can’t afford to have treated. Jason Molina was not well known enough for the circumstances leading to his death to be a teachable moment in the partisan debate over affordable health care. The teachable moment Jason left us is in his body of work, and its suggestion that we look to find a reason to believe.