Deanna Durbin, a star whose songs and smile made her one of the biggest box office draws of Hollywood’s Golden Age, whose fan base included the likes of Winston Churchill and Benito Mussolini, died in late April in a village outside Paris where she had lived, out of public view, since 1949. News of her death was announced by her son, Peter H. David, on April 30, although he indicated she had passed “several days ago.” He gave no cause of death.

One of the biggest stars of the Thirties and Forties, Durbin was, by the time she was 21, not only the highest paid woman in the United States, but the highest paid film actress in the world. A truly international star, she was the number one female film star at the box office in the United Kingdom from 1939 to 1942. Her U.K. fame persists to this day–initial word of the actress’s death was reported on various U.K.-based Durbin fan websites. In her prime Deanna Durbin was such a huge star that she was credited with single handedly saving Universal Pictures from bankruptcy (with an assist from Abbott & Costello).

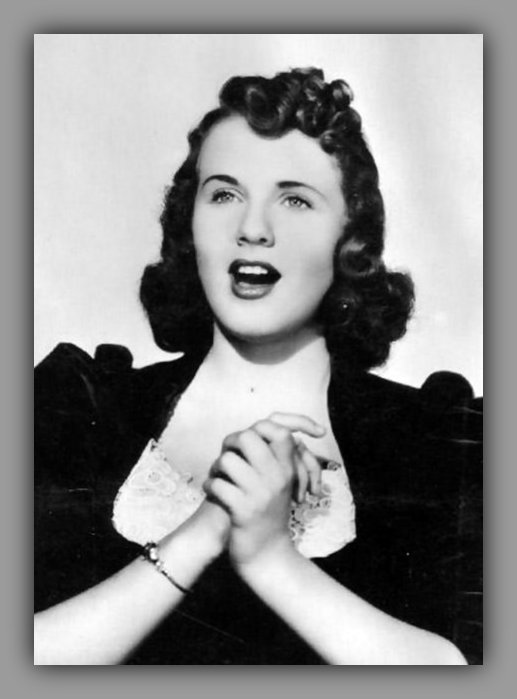

Born Edna Mae Durbin in Winnipeg, Manitoba on December 4, 1921, she was only one year old when her family moved to Los Angeles, California. She began singing as a child, and by age ten was taking professional singing lessons with a legendary vocal coach, Andres de Segurola. He believed that Deanna Durbin had an excellent opportunity to become an opera star. He had been commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera to watch her progress carefully and keep them advised. He said that Deanna already possessed fully developed vocal organs, and her voice would change only in volume as she grew older. Her voice ranged from A below middle C to E above high C. Segurola recommended a delay of three years in her operatic debut, insisting that time would only enlarge and enrich an already mature soprano voice. He described the quality of her voice as “a perfect blue-white diamond, and just as rare–a voice one in ten million.” In addition, he pointed out, she possessed the invaluable assets of charm, poise, and beauty.

She was discovered by a casting director at MGM who was looking for someone to play opera contralto Ernestine Schumann-Heink as a child in a film biography of Miss Schumann-Heink. She won over the colorful head of MGM, Louis B. Mayer, by singing the aria Il Bacio to him over the telephone. He immediately offered her a contract. She made her debut at age 13 in the short, Every Sunday, in which she was paired with another recently signed teenage star, Judy Garland (in the movie, Durbin sang Il Bacio Garland a lively swing number “The Americana”).

Fifteen-year-old Deanna Durbin makes her film debut in Every Sunday (1936), performing the aria Il Bacio to Judy Garland’s swing number, ‘The Americana.’

In the 1939 film Three Smart Girls Grow Up (directed by Henry Koster), Deanna Durbin performs the Thomas Moore-John Stevenson tune ‘The Last Rose of Summer.’

Unfortunately, Durbin would not get the chance to play a young Ernestine Schumann-Heink. The legendary opera star fell ill and died at age 75, at which point MGM abandoned her biopic. In the meantime Durbin’s contract with MGM expired in May 1936. Shortly afterwards she signed with financially struggling Universal, where, first, she put Edna Mae Durbin to rest and adopted the stage name Deanna Durbin. Universal assigned her to Joe Pasternak, who produced ten of her films.

In her first full-length feature, Three Smart Girls (1936), Durbin’s engaging screen presence translated into a box office success and begat an immediate star. A year later, One Hundred Men and a Girl followed suit, saving Universal from bankruptcy and earning the renamed Deanna Durbin the nickname, “the mortgage lifter.”

Deanna Durbin performs ‘Nessun Dorma’ in His Butler’s Sister (1943), directed by Frank Borzage.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kr1zs0wFEgU

From another 1943 film, Hers to Hold (directed by Frank Ryan), Deanna Durbin performs Cole Porter’s ‘Begin the Beguine’

By 1939 child roles were becoming increasingly out-of-reach for Durbin who had grown into a mature young woman. She lost out to Judy Garland for the role of Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz. That same year she received her first on-screen kiss–from Robert Stack in the movie First Love–and it caused such a sensation as to overshadow, for a moment, the daily papers’ coverage of WWII.

In 1938 she received an honorary Academy Award for her “significant contribution in bringing to the screen the spirit and personification of youth.”

Her hair, makeup and on-screen outfits set fashion trends worldwide and were emulated by millions. In the 1941 hit Nice Girl? Durbin, then 20, wore a spangled white organdy dress, ruffled and modestly cut, that became the rage at proms and country club dances across the United States. At the height of her career she was a merchandiser’s dream. In the Thirties and Forties her fans could buy Deanna Durbin dolls, dresses, and countless other items bearing her likeness or name. In 1941 Whitman Publishing Company published two young adult novels by Kathryn Heisenfelt in which Miss Durbin solved mysteries like Nancy Drew: Deanna Durbin and the Adventure of Blue Valley and Deanna Durbin and the Feather of Flame. In 1939 alone the actress made $2 million from merchandising and endorsements.

During the production of Three Smart Girls she began singing on Eddie Cantor’s radio show and created a stir with her pure, captivating voice and sensitive approach. She would continue to appear on The Eddie Cantor Show until 1938, when her commitments to Universal became too demanding of her time. Following the success of Three Smart Girls, she was cast as the lead in her next film, One Hundred Men and a Girl. Over the next several years she starred in Mad About Music (1938), That Certain Age (1938), Three Smart Girls Grow Up (1939), First Love (1939), It’s a Date (1940) and Spring Parade (1940). Singing didn’t exactly take a back seat, though: she signed with Decca Records and recorded some 50 songs for the label.

Durbin began to transition from teen roles to more adult roles starting with 1939’s First Love, that landmark first-screen-kiss film. She also began to assert her power as star. After Joe Pasternak left for MGM in 1941, she refused to appear in the proposed film They Lived Alone. As a result Universal suspended her, although star and studio eventually struck an agreement that gave her approval over her films’ scripts, directors and songs. (They Lived Alone was cancelled.) Durbin also attempted to expand beyond the light musicals in which she had appeared throughout her career, taking instead roles markedly in contrast to those with which she had made her fame, such as the comedy drama The Amazing Mrs. Holliday (1943), the intriguing holiday-themed film noir Christmas Holiday (1944), and the comedy-mystery Lady on a Train (1945). None of these movies captured the film-going public’s fancy. She returned to musicals, including her only Technicolor film, Can’t Help Singing (1944). (All her other films were in black-and-white because studio executives said it was too expensive to pay her salary and film her in color as well.) In 1943 she was offered the lead in Roger and Hammerstein’s original Broadway production of Oklahoma, but Universal refused to loan her out. Lady On a Train was far more important to Durbin than it ever was to her fans or her acting legacy. Its director, Charles David, became her third and final husband, in 1950, and with him she walked away from the movies, settled in France and into a satisfying life as wife and mother, for the remainder of her life refusing all but one request for interviews and all feelers about resuming her acting career.

Deanna Durbin, 18 years old, performs Franz Schubert’s ‘Ave Maria’ in the 1940 film, It’s a Date, directed by William A. Seiter

Deanna Durbin and the Vienna Choir Boys perform Bach/Gounod’s ‘Ave Maria’ in the 1938 film, Mad About Music, directed by Norman Taurog, and featuring William Frawley (Fred Mertz) as Dusty Turner.

One of the greatest of all singing actresses, Durbin’s voice had a surprising maturity about it even in her youth, and its sweet tone was custom made to tug at listeners’ hearts. She was equally at home with sophisticated pop songs, arias and folk songs. Apart from her singing, Durbin on-screen persona was perfect for the war-torn, Depression-ridden years of her greatest successes. Ever optimistic and upbeat, she was a positive cultural icon at a time when the country was sorely in need of one. The adoration she won from fans in those days not only never waned but was passed on from one generation to the next and on into the present. Hers was an irresistible combination of talent, looks, charm and character of rare magnitude.

Another tune from 1938’s Mad About Music, ‘Chapel Bells,’ written by Jimmy McHugh (music) and Harold Adamson (lyrics)

In 1941’s Nice Girl? (directed by William A. Seiter), Deanna Durbin performs Stephen Foster’s ‘Old Folks at Home’

Yet, she was ambivalent–and some would say bitter–about what she had become as part of Hollywood’s dream machine. In 1958, when she abruptly announced her retirement, she sent a farewell letter to some newspaper reporters. “I was a typical 13-year-old American girl,” she wrote. “The character I was forced into had little or nothing in common with myself–or with other youth of my generation, for that matter. I could never believe that my contemporaries were my fans. They may have been impressed with my ‘success.’ but my fans were the parents, many of whom could not cope with their own youngsters. They sort of adopted me as their ‘perfect’ daughter.

“I was never happy making pictures. I’ve gained weight. I do my own shopping, bring up my two children and sing an hour every day.”

In It’s a Date (1940), Deanna Durbin performs the beloved Scottish folk song ‘Loch Lomond’

In Because of Him (1946, directed by Richard Wallace), Deanna Durbin performs ‘Danny Boy’

The sharpest assessment of Deanna Durbin’s impact on the world of her time came courtesy Stuart Mitchner, writing in Town Topics (“Princeton’s Weekly Community Newspaper Since 1946”) on May 14. In “Deanna Durbin’s Star Shone Brightest in the World’s Darkest Hour,” Mitchner observes:

If anything, the Hollywood hype falls short because her impact on a world at war transcended stardom. Stay with the metaphor and you could say she outshone all the stars in Hollywood, whether her light was shining on the battlefield or the homefront, soldiers or civilians, regardless of nationality. The April 30 New York Times obit’s “wholesome, radiant, can-do girl who in a series of wildly popular films was always fixing the problems of unhappy adults” became the “can-do” embodiment of beauty and music and youth symbolically opposed to the problems of a disastrously unhappy world.

When the Japanese wanted to crush the morale of the American families imprisoned at the Santo Tomas internment camp in Manila at the outset of World War II, they released the news that Deanna Durbin had died in childbirth, a sham presented so convincingly that it prompted a memorial service. Since the Japanese banned the use of radios, the prisoners continued to think the “can-do girl” was dead for almost three years, until a makeshift radio pulled in a broadcast from San Francisco and they heard her voice dedicating an evening of music “to the women of the Philippine Islands.”

In His Butler’s Sister (1943, directed by Frank Borzage), Deanna Durbin performs the Russian Gypsy folk song ‘Two Guitar’ (lyrics: Apollon Grigoriev; music, Ivan Vasiliev)

In 1947’s Something In the Wind (directed by Irving Pichel), Deanna Durbin and Jan Peerce perform Guiseppe Verdi’s ‘Il Trovatore’

In 1941’s It Started with Eve (directed by Henry Koster), Deanna Durbin performs Vissi d’arte, an aria from Giacomo Puccini’s opera, Tosca. The star-making five-year association of Deanna Durbin, producer Joe Pasternak and director Henry Koster ended following this film.

On the other side of the world in Amsterdam, Anne Frank was taping two photos of Deanna Durbin on the wall of the secret annex, both from First Love (1939), a variation on the Cinderella story in which Durbin receives her first screen kiss from Robert Stack. Although there are no explicit mentions of the film in Anne’s diary, her frequent references to the developing relationship with Peter and their first kiss suggest that she must have given those images more than a few significant glances in the spring and summer of 1944. The photos remain on the wall, just as they were, at the Anne Frank House museum.

Another Durbin fan, British prime minister Winston Churchill, had no need of photographs; he made sure to see the films before they were released to the general public in the U.K., where she was even more beloved than she was in the U.S.A. Churchill’s special favorite was One Hundred Men and a Girl, in which Deanna helps bring together Leopold Stokowski with an orchestra of out-of-work musicians that includes her trombone-playing father (Adolphe Menjou). Churchill reportedly screened the film on celebratory wartime occasions while enjoying brandy and a cigar. The same movie was also “a great prewar favorite in Japan,” as were all of Durbin’s pictures, according to various sources, including Donald Richie, who says that Akira Kurosawa’s early film, One Wonderful Sunday “takes its concert finale straight from One Hundred Men and a Girl,” while paying homage to Durbin through the “jazzy optimism” of the fresh-faced heroine “pulling for her young man just as Deanna Durbin pulled for Stokowski–same polished cheeks, same tear-filled eyes.” Another example of her following among the Japanese: a Deanna Durbin film, His Butler’s Sister, was the first American movie that General MacArthur’s Occupation Committee permitted to be shown in Japan.

Deanna Durbin sings ‘The Turntable Song (Round an’ Round an’ Round),’ the opening number from 1947’s Something In the Wind. Featuring music by Johnny Green and lyrics by Leo Robin, the song became the final hit from a Deanna Durbin movie. Miss Durbin recorded the tune with Johnny Green and His Orchestra on Decca during a July 22, 1947 recording session–Deanna’s last for the label–which produced a 78-rpm album of four selections from the Green-Robin score, the three other tunes being the title number, ‘It’s Only Love’ and ‘You Wanna Keep Your Baby Looking Right.’

The fact that Durbin’s films were banned in Germany suggests that she was equally popular there; apparently the same was true in Italy, where in 1941 Mussolini published an open letter to “Dearest Deanna” in his official newspaper asking her to intercede with President Roosevelt “on behalf of American youth” to convince FDR not to become involved. The letter spoke of how “we always had a soft place in our heart for you” but that “today we fear that you, like the remainder of American youth, are controlled by the President and perhaps tomorrow will see fine American youth marching into battle in defence of Britain.”

Around the time Mussolini was calling on Deanna to intercede with Roosevelt (she sang Schubert’s “Ave Maria” at the memorial concert for FDR), her “hair, makeup, and on-screen outfits set fashion trends worldwide and were emulated by millions,” according to the AP obituary. In the 1941 hit Nice Girl?, the “spangled white organdy dress, ruffled and modestly cut” worn by 20-year-old Deanna “became the rage at proms and country club dances across the United States.” The teen-age soldiers-to-be who went to those dances with the girls in white organdy might lust for pin-up cheesecake like Rita Hayworth and Betty Grable, but Deanna was the girl of their lovesick dreams and deepest hopes. A soldier from England told her that she epitomized “Sincerity, tenderness, music, and laughter … it is just a little piece of Heaven to be able to visit the garrison cinema, see you and feel the sweetness and peace which surrounds you.”

This video shows fan mail to Deanna Durbin from her 12-year career–much of which comes from areas of strife during WWII. POW, Internee, censored, adversit, and interrupted mail is shown. Posted at YouTube by tjrmovieman.

Durbin also had admirers in the arts. Cellist and composer Mstislav Rostropovich cites her as one of his most important musical influences in an interview from the mid-1980s: “She helped me in my discovery of myself. You have no idea of the smelly old movie houses I patronized to see Deanna Durbin. I tried to create the very best in my music, to try and recreate, to approach her purity.” And when Indian director Satyajit Ray accepted a Lifetime Achievement Oscar in 1992, he mentioned Deanna Durbin as the only cinema personality of the few he wrote to who had acknowledged his boyhood fan letter with a personal reply.

Durbin married cinematographer Vaughn Paul in 1941, and was divorced in 1943. In 1944 she married playwright Felix Jackson, 20 years her senior. They had one daughter and divorced in 1949. Charles David, her third husband, died in 1999. She is survived by her daughter, Jessica Jackson, and her son, Peter H. David.

The Essential Deanna Durbin on Disc

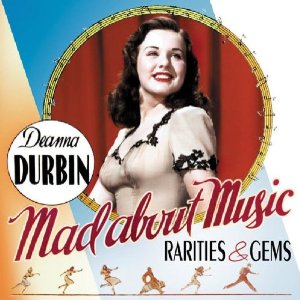

MAD ABOUT MUSIC: RARITIES & GEMS

A collection of songs recorded for but not used in her movies, including alternate takes with extra verses and modified sections.

In 1971, after countless reissues of Deanna Durbin’s commercial recordings, Decca Records released selections of her soundtrack recordings on one LP. The problem was that they were taken directly from the films themselves, complete with extraneuos noise and dialogue; and the tracks were mastered in the then popular “simulated stereo” which resulted in too much reverb. However, this new release from Sepia Records, “Mad About Music”, finally approaches the soundtrack recordings of Deanna Durbin in a manner more deserving of the beautiful soprano motion picture star. The recordings themselves are from Hisato Masuyama’s extensive collection of original Universal Studio lacquers and publicity release 78 rpm records, and folks, they sound magnificent. Yes, there are slight noises and cues by studio workers that give away their age and sources, but having a few of these original records myself, it’s easy to hear how their new CEDAR 24 bit mastering has worked wonders with the material. Several of the songs on the CD that are also on the origial LP include “Lover”, “Danny Boy”, “The Old Refrain”, “Russian Medley” and “Night And Day”; each sounding so much better than their earlier incarnations. Then there are the tracks, most never before available to the record buying public: “I Love To Whistle”, “Say a Pray’r for the Boys Over There”, “Gimme A Little Kiss, Will Ya Huh?” three selections from Durbin’s film, “Something in the Wind”, and “Always” from “Christmas Holiday”, complete for the first time with the refrain. (When is Universal going to finally release this Gene Kelly/Deanna Durbin thriller on DVD?) There are twenty three generous tracks accompanied by a booklet that is lavishly stuffed with interesting liner notes and sixteen beautiful color and black and white photos of Durbin and her film posters. —Bruce K. Hanson at Amazon.com

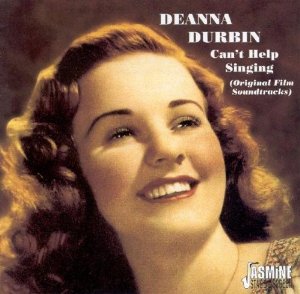

CAN’T HELP SINGING (Original Film Soundtracks)

Rarities like “Say a Prayer For the Boys Over There” and the beautiful “La Estrellita” are included alongside other hard-to-find gems such as “It’s Raining Sunbeams.” The more familiar songs are ever ripe: “Love Is All” is one of the most beautiful songs ever written and this version by Ms. Durbin is as resonant and lovely as “More and More” and “My Own.” The icing on the cake here, however, is “The Turntable Song,” the bouncy pop song from Something In the Wind, recorded with Johnny Green and His Orchestra and written by Leo Robin and Johnny Green, was the final single to emerge from a Deanna Durbin movie.

THE ULTIMATE COLLECTION: 24 GREATEST HITS (Import)

For American fans, the title of this album is a bit misleading, because there were no charts in Britain, from whence this import springs, and the Billboard charts from Ms. Durbin’s career show her only American chart hit to be “My Own,” from the film That Certain Age. It peaked at #39. Otherwise, it could be argued these are at least 24 of the artist’s finest vocal performances on record. Tracks include the Bach/Gounod “Ave Maria,” Irving Berlin’s “Always,” “My Hero,” “When the Roses Bloom Again,” “Love’s Old Sweet Song,” “Waltzing in the Clouds,” the irresistible “It’s Raining Sunbeams” (so buoyant and upbeat it surely must have inspired Marvin Hamlisch’s “Sunshine, Lollipops & Rainbows,” the hit he penned for Lesley Gore), “Because,” et al.

SPRING PARADE (Original Soundtrack) (Sepia Recordings)

Only a handful of actual original soundtrack recordings exist from Deanna Durbin’s many films, but of these Spring Parade has been accurately described as the Holy Grail of Durbin soundtracks–only 25 sets of the original 78 RPM recordings were pressed and those were given to the film’s production crew. The music here has been remastered from those 78 RPM sources, yielding for public consumption, finally, the complete soundtrack from this 1940, Henry Koster-directed musical comedy that earned four Academy Award nominations (for Best Original Song, Best Music and Best Cinematography and–hey, hey!–Best Sound Recordings. Songs include “It’s Foolish but It’s Fun,” “When April Sings,” “Blue Danube Dreams” and the Oscar-nominated “Waltzing In the Clouds.” This complete soundtrack also contains the film’s extended orchestral sequences and incidental music that came along with the great songs penned by Gus Kahn (lyrics) and Robert Stoltz (music). As a bonus–as if such is needed–some additional Durbin rarities have been added, including “exploitation” discs recorded for not only Spring Parade but also for her films Three Smart Girls and That Certain Age. These promotional recordings, containing copious extracts of Deanna’s musical numbers, were specifically created for use on radio and in movie theaters;, it’s a miracle they have survived, and yet another reason to rank Spring Parade among Ms. Durbin’s essential recordings.