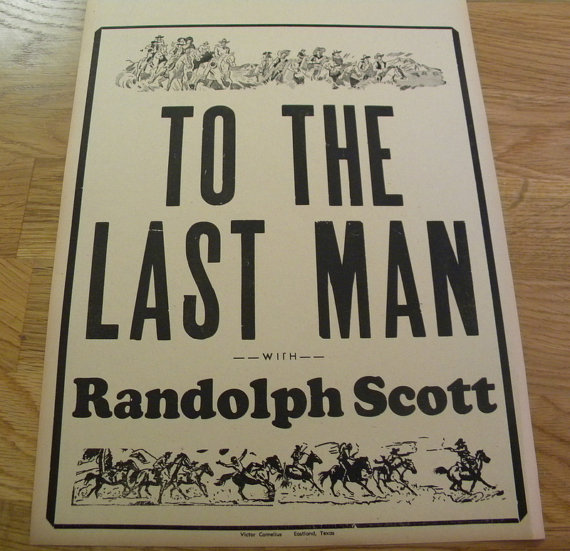

Directed by Henry Hathaway

Produced by Harold Hurley

Written by Zane Grey (story), Jack Cunningham (screenplay)

Starring: Randolph Scott, Esther Ralston, Jack La Rue, Buster Crabbe, Barton MacLane, Noah Beery, Shirley Temple (as Mary Stanley, uncredited), Jay Ward

Cinematography by Ben F. Reynolds (as Ben Reynolds)

To The Last Man, a 1933 Paramount production is not only well-made with an excellent cast, but occupies an key place in the filmographies of Randolph Scott, Shirley Temple and director Henry Hathaway. Sadly, it apparently survives only in murky, mangled, splice-filled third-generation dupes.

Paramount co-founder Jesse L. Lasky acquired the screen rights to a number of books by the Western author Zane Grey in the early 1920s and turned them into big-budget A films with stars like Richard Dix and Gary Cooper in a series that ran into the early talkie era. In 1932, the studio assigned Hathaway, who had worked as an assistant director on no fewer than seven silent Grey films, to move up to the director’s chair for Heritage of the Desert, the first in an eight-year-long series of B-movie remakes with interesting casts and solid production values (as well as stock footage from the silent versions) that were mostly filmed on location at property Paramount owned in Lone Pine, Calif. That’s also where Paramount also shot an even longer-running B-Western series devoted to the adventures of Hopalong Cassidy, as well as any number of “A” pictures (including George Stevens’s 1939 classic, Gunga Din, starring Gary Cooper, in which Lone Pine’s Alabama Hill stood in for colonial British India), including Hathaway’s India-set Lives of a Bengal Lancer.

Most of the earlier efforts in the series starred Scott, who had been in films since 1928, mostly in unbilled bit parts, among other things playing one of the half-men in the horror film The Island of Lost Souls, made before but released by Paramount just after Heritage of the Desert. Though Scott dabbled in everything from musicals (High Wide and Handsome and two Astaire-Rogers opuses) to comedies (My Favorite Wife with longtime roommate and maybe-more Cary Grant) through the 1940s, it was these B-westerns that established him as a durable western star in a career that culminated in his celebrated ’50s cycle with director Budd Boetticher and his memorable swan song with Sam Peckinpah, Ride the High Country.

Arugably the best of the Hathaway-Scott films is the fifth, To the Last Man, previously filmed by Paramount in 1923 starring Richard Dix, with Hathaway assisting director Victor Fleming (like most of Fleming’s silent output, it either crumbled to dust or was melted down for its silver content decades ago). In the remake, Scott and silent screen star Esther Ralston play a Kentucky backwoods Romeo and Juliet caught up in a longtime feud between their gun-toting families. Scott’s younger brother is played by Larry (“Buster”) Crabbe, as he was then billed, who starred in several subsequent entries after Scott graduated from the series. His older brother is portrayed by Barton MacLaine, with another up-and-comer, Gail Patrick, as his wife.

The real scene-stealer is their young daughter, an unbilled Shirley Temple in only her third feature film appearance. While filming one scene in which she has a tea party with a mule, the animal kicked Shirley twice, and Shirley spontaneously kicked right back. Hathaway left this delightful improvisation in the film. In an even more astonishing sequence, the film’s estimable bad guys–Noah Berry Sr., reprising his role from the 1923 version, and Jack LaRue–shoot the head off Shirley’s doll, and she bursts into tears. Shirley was so impressive that Hathaway urged Paramount to sign Temple to a contract. The studio long regretted making only a two-picture deal–Little Miss Marker and Hathaway’s Now and Forever made her a full-fledged star, but by the time they were released in 1934, Shirley was already under contract to Fox, where Scott subsequently suppported her in Susannah of the Mounties and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm.

To the Last Man climaxes with a landslide that obviously uses stock footage recycled from the ’23 production, but it’s a tight, surprising dark and impressive little movie. Ed Hulse, author of Zane Grey on Film, says it’s part of an informal Hathaway trilogy that includes his later Technicolor epics The Trail of the Lonesome Pine with Henry Fonda and Shepherd of the Hills starring John Wayne, both also filmed in the Lone Pine area after Hathaway became one of Paramount’s top directors (after a long spell at Fox, Hathaway (whose stature as an auteur has been growing in recent years) returned to Paramount to direct Wayne to an Oscar in True Grit). The two later titles in the trilogy have been beautifully restored and preserved by their present owner, Universal Pictures, whose corporate predecessor MCA bought the vast majority of Paramount’s pre-1948 talkies in 1956. –By Lou Lumenick, excerpted from his essay, “Film Preservation’s ‘Grey’ area: Shirley Temple, Randolph Scott and Public-Domain Hell,” in the New York Post, February 17, 2010

Selected short: Superman in ‘The Magnetic Telescope’

Directed by Dave Fleischer

Superman voiced by Bud Collyer

Released: April 24, 1942

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gHBwTjJcXss

In “The Magnetic Telescope,” the sixth entry in the Superman series, yet another evil scientist attracts “flaming comets” with a ridiculously looking magnetic telescope.

As one comet has destroyed part of the city, the police try to stop the villain from hauling in another one. But their attempts make the professor lose control over the comet, and while destruction is at hand, Lois phones the Daily Planet from the laboratory. When her call ends in a scream, Clark Kent rushes… er… takes a cab to the laboratory. Only when the cab is stopped by one of the comet’s offshoots, he changes into Superman and flies up there…

Superman, of course, saves the day. He first tries to stop the comet itself (which falls remarkably slowly), but surprisingly, this is too much for him, and his antics produce more offshoots, which destroy bridges and such. So, in a bright moment he restores power to the magnetic telescope, telling Lois to put the machine on “reverse”… (how Superman came to know how the telescope works, we’ll never know…).

The whole story is amazingly ridiculous, especially because the story is told in the most sincere fashion. It shows the Fleischer studio’s discomfort with realism all too clearly.

The all too powerful comet is a minor surprise within the formulaic Superman series. But “The Magnetic Telescope” has two other deviations from the story formula: in this entry Clark Kent doesn’t say his usual ”this looks like a job for Superman”,’ and Lois manages to kiss Superman, who, unfortunately turns out to be Clark Kent, after all… –from Dr. Grob’s Animation Review

Background: The Fleischer & Famous Superman cartoons are a series of seventeen animated Technicolor short films released by Paramount Pictures and based upon the comic book character Superman.

The pilot and first eight shorts were produced by Fleischer Studios from 1941 to 1942, while the final eight were produced by Famous Studios, a successor company to Fleischer Studios, from 1942 to 1943. Superman was the final animated series initiated under Fleischer Studios, before Famous Studios officially took over production in May 1942.

The first nine cartoons were produced by Fleischer Studios (the name by which the cartoons are commonly known). In 1942, Fleischer Studios was dissolved and reorganized as Famous Studios, which produced the final eight shorts. These cartoons are seen as some of the finest, and certainly the most lavishly budgeted, animated cartoons produced during The Golden Age of American animation. In 1994, the first entry in the series was voted #33 of the 50 Greatest Cartoons of all time by members of the animation field.

By mid-1941, brothers Max and Dave Fleischer had recently finished their first animated feature film, Gulliver’s Travels, and were deep into production on their second, Mister Bug Goes to Town. They were reluctant to commit themselves to another major project at the time when they were approached by their distributor, and owner since May 1941, Paramount Pictures. Paramount was interested in cashing in on the phenomenal popularity of the new Superman comic books by producing a series of theatrical cartoons based upon the character. The Fleischers hoped to discourage Paramount from committing to the series, so they informed the studio that the cost of producing such a series of cartoons would be about $100,000 per short—an amazingly high figure, about four times the typical budget of a six-minute Fleischer Popeye the Sailor cartoon during the 1940s. To their surprise, Paramount negotiated it down to a budget of $50,000–half the requested sum, but still two times the cost of the average Fleischer short—and the Fleischers were committed to the project.

The first cartoon in the series, simply titled Superman, was released on September 26, 1941, and was nominated for the 1941 Academy Award for Best Short Subject: Cartoons. It lost to Lend a Paw, a Pluto cartoon from Walt Disney Productions and RKO Pictures.

The voice of Superman for the series was initially provided by Bud Collyer, who also performed the lead character’s voice during the Superman radio series. Joan Alexander was the voice of Lois Lane, a role she also portrayed on radio alongside Collyer. Music for the series was composed by Sammy Timberg, the Fleischers’ long-time musical collaborator.

Rotoscoping, the process of tracing animation drawings from live-action footage, was used minimally to lend realism to the human characters and Superman. Many of Superman’s actions, however, could not be rotoscoped (flying, lifting very large objects, and so on). In these cases, the Fleischer lead animators, many of whom were not trained in figure drawing, animated roughly and depended upon their assistants, many of whom were inexperienced with animation but were trained in figure drawing, to keep Superman “on model” during his action sequences.

The Fleischer cartoons were also responsible for Superman being able to fly. When they started work on the series, Superman could only leap from place to place (hence “Able to leap tall buildings in a single bound” in the opening). But they deemed it as “silly looking” after seeing it animated and decided with Detective Comics Inc.’s permission, to have him fly instead. (Source: Wikipedia)