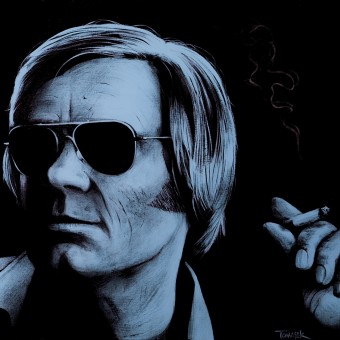

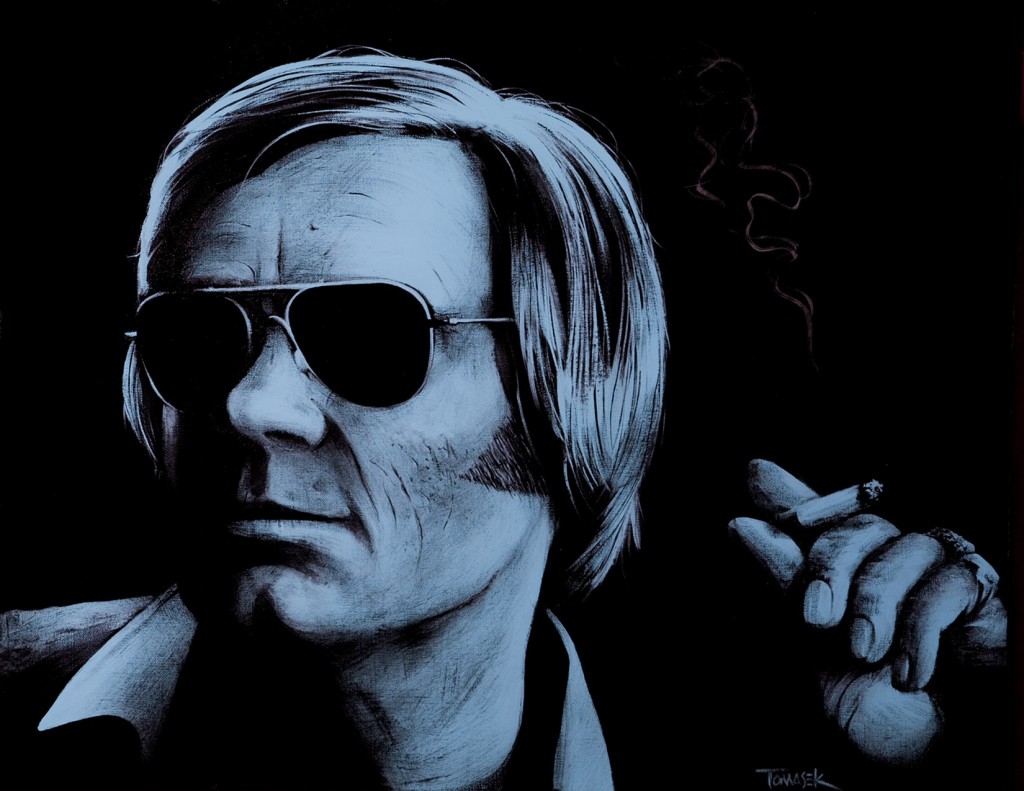

A commissioned portrait of George Jones by Nashville-based artist/musician Dean Tomasek. This and other works by the artist—Nature, Portraits, Posters, Design, Woodworks—are available at his website, www.deantomasek.com.

As virtually every publication in the known world has apparently reported, George Jones, one of country music’s greatest singers, died on April 26. He had been hospitalized at Vanderbilt University Hospital since April 18, suffering from a fever and irregular blood pressure. He had announced that his final concert would be on November 13, 2013 at Nashville’s Bridgestone Arena, and that a forthcoming duet album with Dolly Parton would be his final studio recording. Jones is survived by his third wife, Nancy (maiden name Sepulvedo), whom he wed on March 4, 1983. His first marriage, in 1950, to Dorothy Bonvillion, lasted a year and produced one child, a daughter, Susan. In 1954, Jones married Shirley Ann Corley, by whom he fathered two sons, Jeffrey and Bryan, before the marriage ended in 1968. His third marriage was to Tammy Wynette on February 16, 1969. They remained married until March 13, 1975, and had a daughter, Tamala Georgette, who, as Georgette Jones, is a country singer, and occasionally performed on stage with her father. In addition to Nancy, Jones’s children and grandchildren survive him, along with a sister, Helen Scroggins.

The most concise appraisal of Jones’s life and career comes by way of Bill C. Malone’s essential Country Music USA, excerpted below. In addition, since Mr. Malone’s entry concludes in the ‘80s, we offer our own listener’s guide to some essential George Jones recordings of later years that cover not only his classic sides and must-have reissues but the still-vital but often overlooked work he did on record in the ‘90s and early oughts.

‘One of the Legendary Singers’

from Bill C. Malone’s Country Music USA

George Jones was at the center of a honky-tonk resurgence in the early sixties that stretched from his native Texas to California. These years marked the maturing of the vocal style that would make him one of the legendary singers of country music. Jones was born on September 12, 1931, in Saratoga, Texas, in the midst of a heavily forested area known as the Big Thicket, and very near the sites of some of Texas’ earliest oilfields. His working class parents represented the moral and social dichotomy that often surfaced in rural southern families: his hard-working father (a log ruck driver, an oil worker, a shipyard worker) often sought solace from disappointment and poverty in music and the bottle; his mother, on the other hand, found her comfort in sobriety and fundamentalist religion. George absorbed traits from both parents, a love for music from both of them, but, unfortunately, a fatal weakness for whiskey from his father. He sang in his mother’s church (the Full Gospel Tabernacle Church in Kountze, Texas), but the songs of the radio were much more appealing. He listened faithfully to the Grand Ole Opry and found his first heroes in Bill Monroe and Roy Acuff. Acuff’s influence was powerful in the singing of the early George Jones, and even today one can hear a trace of the Acuff sound, especially in Jones’s phrasing on high notes.

The Jones family moved to Beaumont in 1942, following the lure of war-related jobs in that industrial sector of Southeast Texas. As thousands of rural Texas families poured into cities lie Beaumont, Port Arthur, Texas City and Houston in search of defense work, the country music-honky-tonk culture expanded to exploit their needs and satisfy their desires. Jones was not old enough to be a regular participant in this dance-hall culture, but he learned the songs that issued from it, and he developed an unquenchable desire to be a professional singer. In about 1943, when he was only twelve years old, Jones began singing on the streets of Beaumont or anywhere that a crowd was willing to listen. A charming photograph from this period shows a serious, two-headed youngster walking along a Beaumont street and strumming a guitar. From this point on nothing but music could satisfy Jones, and by the time he was fourteen he was performing on radio stations in and near Beaumont. In 1948 he fell under the spell of Hank Williams, and that great singer became the kind of model and inspiration that Bill Monroe and Roy Acuff had earlier been. During a two-year stint in the Marines, from November 1951 to November 1953, Jones continued to sing as often as he could, particularly at a dance hall in Redwood City, California, near Camp Pendleton. When he returned to Beaumont, he was ready to being his full-time professional career.

‘In about 1943, when he was only twelve years old, Jones began singing on the streets of Beaumont or anywhere that a crowd was willing to listen. A charming photograph from this period shows a serious, two-headed youngster walking along a Beaumont street and strumming a guitar.

In January 1954 Jones made his first recordings for Starday, a company only recently organized in Beaumont by Jack Starnes and Harold W. “Pappy” Daily. The early Starday records were made at Starnes’ residence in Beaumont, and they provided a wonderful means of exposure for the wealth of talent which played in the area from Louisiana through Southeast Texas to Houston (the label’s first big hit was “Y’all Come,” written and recorded by former Texas schoolteacher and long-time radio personality Arlie [Arleigh] Duff). Jones’ first recordings, “No Money in This Deal” and “You’re In My Heart,” were rollicking and slow respectively, an accurate prophecy of the alternating styles he would feature for the rest of his career. A 1955 release, “Why Baby Why,” made the national popularity charts, but Red Sovine and Webb Pierce’s duet version was more successful. Nevertheless, Jones became sufficiently nown and appreciated to be named to the cast of the Louisiana Hayride, where he stayed for three months before moving on to the Grand Ole Opry in August 1956. By 1957 he had followed his producer and manager Pappy Daily to the larger Mercury label and there he began carving out his own identity while making the first of his classic honky tonk recordings. Under Daily’s constant admonition to “sing like George Jones,” he began casting off most of the vocal mannerisms borrowed from other singers. In turn, he developed the intense and unique style that has enthralled a generation of listeners. For the two or three minutes consumed by a song, Jones immersed himself so completely in its lyrics, and in the mood it conveys, that the listener can scarcely avoid becoming similarly involved.

George Jones’s first Starday recording, ‘No Money In This Deal’ (1954)

Jones affects a Hank Williams style in ‘You’re In My Heart,’ the flip side of “No Money In This Deal’

Jones’s first charting single, 1955’s ‘Why Baby Why’

Although Jones has excelled in the performance of umtempoed, novelty songs, such as “White Lightning” (his first number one Billboard hit), “Who Shot Sam,” and “The Race Is On,” his real strength is deployed in slower songs, particularly in the heart-wrenching complaints of unrequited or broken love. Some of his most powerful performances in this vein came in 1957 and 1958 when he recorded “Don’t Stop the Music,” “Just One More Time,” and “Color of the Blues.” Jones’ searing emotional singing on these songs was almost undisciplined in its passion, but one could hear the stylistic traits that have made him famous: the alternating low moans and high wails, the bending and lengthening of note to almost incredible lengths, and the enunciation of words either with rounded, open-throated precision or through clenched teeth.

1958’s ‘Color of the Blues’: ‘Jones’ searing emotional singing…was almost undisciplined in its passion, but one could hear the stylistic traits that have made him famous…’

Jones’ first real dominance in country music came in the early sixties. He now sang typically in a lower and fuller register, and his managers began adding background voices and lusher instrumental accompaniment to his recordings. But no matter how full and engulfing these accouterments might be, they could not blunt or hide his distinctiveness. He remained a hard country singer. Beginning with “The Window Up Above” in April 1960 and extending on through the sixties with an almost unending stream of hits such as “Tender Years,” “She Thinks I Still Care,” A Girl I Used to Know,” and “Walk Through This World With Me,” Jones strengthened his popular appeal and solidified his reputation as “a singer’s singer,” winning the admiration of singers as disparate as Waylon Jennings, Elvis Costello, Emmylou Harris, James Taylor, and Merle Haggard.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=owWNCNyEuYI

George Jones, live on the Pet Milk Grand Ole Opry show, 1962, ‘She Thinks I Still Care’

…

The most remarkable remarkable example of endurance shown by a honky tonk singer has been that of George Jones. Few singers have achieved such artistic and commercial heights while descending to such personal depths of misery and self-abuse. From 1969 to 1975 he was married to Tammy Wynette, a dream pairing from the standpoint of fans, and once they began recording together they were described as “the president and first lady” of country music. Their years together were commercially rewarding for both singers—their duet performances were popular, and Jones made some of his best solo recordings—but he could not control his urge to drink, nor the violent outbursts that sometimes accompanied his drinking bouts. Jones’ marital difficulties and alcohol binges were the stuff of soap opera, especially when accompanied by the periodic announcements of his ”reform” and rehabilitation. His problems only made him more attractive to fans, and the lyrics of his heart-wrenching songs were often equated with the distress of his life.

‘The president and first lady’ of country music: George Jones and Tammy Wynette, ‘Golden Ring’ (#1, 1976), a live performance from 1982

George and Tammy, ‘We’re Gonna Hold On’ (#1, 1973)

In the years following his divorce in 1975, Jones’ personal life deteriorated even further, his acute alcoholism being complicated by cocaine addiction. He became notorious for missing, arriving late or showing up drunk for concerts (“No Show Jones” was a term often applied to him). But through it all, Jones remained intensely commercial and, in fact, began winning more music industry awards than at any previous time in his career. His resurgence is owed in large part to the skillful direction of Billy Sherrill, who became Jones’ record producer in 1972. Jones, the traditionalist whose heart lay with the hard-core country music of his youth, and Sherrill, the sophisticated producer who seemed wedded to no particular style of music, constituted a highly unlikely but successful partnership. The son of an Alabama preacher, Sherrill served an apprenticeship with Sam Phillips in Memphis, but was working for Epic Records (a subsidiary of Columbia) in 1966 when he produced the first of a long string of hits, David Houston’s “Almost Persuaded.” Sherrill had a keen ear for commercial songs, many of which he wrote himself, and an acute perception of music audience tastes. Many singers, including Charlie Rich, Tammy Wynette, Johnny Paycheck, Tanya Tucker, Johnny Duncan, and Janie Fricke, have profited from his direction. George Jones was no exception. While many fans and critics complained about the elaborate and lush instrumental and vocal arrangements that sometimes threatened to smother the singer’s individuality, the Jones-Sherrill team produced some of modern country music’s biggest hits and some of Jones’ finest performances: “The Grand Tour,” “If Drinking Don’t Kill Me,” The Same Old Me,” “Shine On,” and the 1980 Grammy Award winner, “He Stopped Loving Her Today.”

‘He Stopped Loving Her Today,’ 1980 Grammy Award winning single (#1 country), produced by Billy Sherrill

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ApiRp8zGsUw

‘The Grand Tour’ (1974, #1 country), produced by Billy Sherrill

A great live performance of ‘If Drinkin’ Don’t Kill Me (Her Memory Will).’ The 1981 single was #8 country.

Postscript (by David McGee): With the rise of country’s new generation, the so-called New Traditionalists, in the ‘80s, George Jones, who was embraced by the younger breed as a pioneering artist, stayed on a hot commercial roll, notching 17 consecutive top 20 singles between 1980 and 1987; many of those singles peaked in the Top 10 in fact and three topped the chart. In the ‘90s, though, with Garth Brooks ushering in a new era of rock-based arena country (Brooks himself waxed rapturous over KISS and even cut a track for a KISS tribute album, singing in a voice that sounded nothing like his country voice), Jones’s chart successes waned, as did country radio’s interest in him. But he always had a label home—be it Epic, MCA, Asylum, Bandit—and there would be an occasional breakthrough when he seemed to flex his commercial muscle of old, as with 1993’s enthusiastically received “High Tech Redneck,” which kicked off a productive tenure with MCA Nashville. Ironically enough, his last Top 30 country hit was a duet with the artist whose mega-success changed the course of country music history and helped usher Jones’s generation off the chart, one Garth Brooks, on the #24 charting 2001 single, “Beer Run (B Double E Double Are You In?).” His final single release, which did not chart, was a duet with Georgette Jones, his daughter by Tammy Wynette, on “You and Me and Time,” from the album, Burn Your Playhouse Down: The Unreleased Duets, which peaked at #15 country.

A Selective George Jones Discography: Key Releases from the Later Years

THE ESSENTIAL GEORGE JONES

Epic/Legacy (2006)

George Jones has enough hard-core fans to make any collection that dares bill itself as “essential” a topic of heated debate among the cognoscenti. That said, this double-CD, 40-cut retrospective does an outstanding job of charting the career arc that made Jones the most influential country vocalist of his time and, by some estimates, of all time. The story that’s told here is of a career shaped wholly by two producers, namely Harold “Pappy” Daily, who signed Jones to his Texas-based Starday label in 1954, and Billy Sherrill, who brought Jones to Epic in 1970 and made him a legend–the only cut here not produced by one or the other of them is the final one, 1999’s “Choices,” a brutal bit of autobiographical remorse produced by Keith Stegall for Jones’s powerful Cold Hard Truth album. Working with Daily through the ’60s, Jones stayed true to a honky tonk ethos but evolved from emulating Hank Williams (1954’s “No Money In This Deal” is so Hank it’s scary) to copping some Carl Perkins phrasing (“Just One More,” from 1956, is a good example) to establishing his own skewed, oft-imitated, emotionally gripping phrasing by the time of 1960’s loping honky tonk heartbreaker, “Out Of Control.” After signing Jones to Epic, Sherrill built on some of Daily’s more extravagant touches (notably the pop-influenced background singers heard on cuts such as the #2 single from 1960, “The Window Up Above”), adding discreet strings to that formula and building up the instrumental tracks. The spectacular results occupy the last third of Disc 1 and all of Disc 2, including a couple of duets with Tammy Wynette among enduring monuments such as “The Grand Tour,” “He Stopped Loving Her Today,” “The Battle,” and 1982’s “I Always Get Lucky With You,” Jones’s last #1 with Sherrill. Remastered and well annotated, The Essential is a for-sure keeper. –David McGee

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kunv93ab9Qs

‘I Always Get Lucky With You,’ Jones’s last #1 collaboration with producer Billy Sherrill (1982)

PLAYLIST: THE VERY BEST OF GEORGE JONES

Legacy Recordings (2009)

There are times, listening to George Jones, when it seems like not just the entire emotional range of country music, but its very history, is coursing through his voice and veins. That’s probably because, from uptempo numbers made for rollicking good times to slow ballads made for shedding tears in beers, this true Texas troubadour infuses everything he sings with both honesty and respect: for the tales being told, the feelings being exposed, and the traditions being upheld.

Those qualities, of course, have helped Jones retain his status as country music’s single most admired vocalist for so many decades that it can be tempting to take him, and his artistry, for granted. But anyone who knows even a bit of his biography can tell you that an awful lot of hard work–and yes, hard living–went into building his legend. From the streets of Beaumont where his father sent him off to perform for tips at age eleven in 1943 and the Houston honky tonks where he learned how to play and drink till all hours of the night while still a teenager, to a marriage, divorce and stint in the Marines before turning 22, Jones already had plenty of reality-based experience to channel into his music when he began recording in 1954.

George Jones, ‘The One I Loved Back Then (The Corvette Song),’ a live version of Possum’s #3 single (released 1985)

Along with the influence of such touchstones as Roy Acuff, Bill Monroe, Hank Williams and Lefty Frizzell, it all helped shape a style and image that by the end of the 1960s was at once completely distinctive but also somewhat difficult to properly harness, on stage and off. In 1971, though, Jones joined Epic Records, the recording home of his new bride Tammy Wynette, and under the direction of producer Billy Sherrill (who’d recently helped catapult Wynette to major stardom), Jones began a series of recordings which over the next two decades would forever secure his place in the country music pantheon.

Included here are numerous examples of Jones’ uncanny ability to get completely inside the lyrics of a song so as to reveal their most inner truths. On such ballads as “A Picture of Me (Without You)” and “The Grand Tour,” he manages to convey heartbreak without sounding maudlin–no easy feat, especially for a virile male singer. On the great classic “He Stopped Loving Her Today,” he goes even further, turning a potentially depressing weeper into arguably the most powerful torch song ever. Elsewhere, on such whiskey-steeped tunes as “If Drinkin’ Don’t Kill Me (Her Memory Will)” “A Drunk Can’t Be A Man,” and “I Just Don’t Give A Damn,” Jones bares the inner workings of a conflicted soul–which, as per the personal demons he was fighting during this period (from drug and alcohol abuse to financial and marital problems), ring painfully true.

George Jones, ‘Who’s Gonna Fill Their Shoes’ (1985)

It’s not all devastation and damnation, though. As noted on the autobiographical “I Wanta Sing,” Jones’ desire to “sing songs that make me happy” has remained strong even through his darkest hours, and you can hear both strength and optimism returning to his outlook on such frisky fare as “She’s My Rock,” and “The One I Loved Back Then (The Corvette Song),” both of which hearken back to his earliest days as rockabillying “Thumper” Jones.

Fittingly, this collection ends with 1985’s “Who’s Gonna Fill Their Shoes,” a tune that references musical giants Elvis Presley, Conway Twitty, Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Charlie Rich, Marty Robbins as well as ol’ Hank and Lefty. “You know the world is filled with singers, but only just a few are chosen to tear your heart out when they sing,” notes Jones. “Who’s gonna give their heart and soul to get to me and you?” he asks. Thankfully, as of 2009 the old Possum remains one of that chosen few still alive and kicking. As the title of his best-selling 1996 autobiography says, “I Lived To Tell It All.” –Billy Altman

COLD HARD TRUTH

George Jones

Asylum (1999)

At the time of his near-fatal auto accident in 1999, George Jones was finishing his first Asylum album, Cold Hard Truth, and had plans to go back in the studio to polish up some of his vocals. His extended recuperation prevented that, but you’d never know it from the finished product. Cold Hard Truth stands as a monument in Jones’s monumental catalogue, a fact evident from the first mournful notes he sings in the autobiographical opener, “Choices,” a quiet, touching bit of owning up that would be hard to take if it weren’t so downright beautiful. Then, as you’re waiting to exhale, Jones lays on the heartbreak again with the title song, wherein he sings as his own conscience, cataloguing the selfish deeds that cost him a good woman’s love and, in effect, a future. Tough stuff — and Jones’s reading of the title sentiment cuts to the bone. It gets deeper as it goes along–“Our Bed of Roses” will get the tears flowing, too–but Possum leavens the noir with some good-time uptempo frolics, chief among them being the Mark Collie-Dean Miller instant dance hall classic, “Ain’t Love A Lot Like That,” complete with Brent Mason’s twangy guitar, Hargus “Pig” Robbins’s rinky-tink piano, and Paul Franklin’s feisty pedal steel commentary. But oh, those tearjerkers, as priceless as this album is essential. –David McGee

A live version of the wrenching ‘Choices,’ from the 1999 album, Cold Hard Truth

THE ROCK: STONE COLD COUNTRY 2001

George Jones

Bandit (2001)

Time is George Jones’ great ally, because the longer he hangs around planet Earth, the better records he makes. Not as dark and foreboding as 1999’s Cold Hard Truth, one of Possum’s grandest moments, The Rock nonetheless offers more than a few object lessons in country singing that cuts to and through the bone. What Jones does with Karen Staley’s honk tonk tearjerker, “Half Over You,” is bound to break hearts all up and down the line as Jones describes the forlorn first moments after a love affair goes south. “I Am” is one of the more curious entries in the Jones oeuvre, being the story of a man unable to do anything but live up to the archetype of the modern male as strong, silent and emotionally distant. But the anguish in the measured doses of Jones’ phrasing, so emblematic of the expectations he wants to buck, is almost palpable, and it’s chilling–you go back again and again to be sure you heard what you think you heard. “What I Didn’t Do” is an exercise in self-loathing rivaling the searing revelations of his previous album’s title track, a litany of failings that cost him a good woman’s love. And the atmospheric, fiddle- and pedal steel-fired evocation of the Hank Williams legend in Billy Joe Shaver’s “Tramp On Your Street” is the perfect honky tonk finale to another Jones tour de force (Possum even tosses in one of his trademark “elvry” phrasings here, supplanting the mundane “every” of normal discourse). Of course there’s time for tomfoolery, in the form of a rambunctious duet with Garth Brooks on “Beer Run (B Double E Double Are You In?)” and a brisk, shuffling tribute to a solid, stubborn rock of a dad in “The Man He Was.” But oh, those cold hard truths about the way we live our lives—The Rock extracts a price for clambering over it. –David McGee

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EsCGtq-Lmzg

Possum makes a personal statement of Karen Staley’s honky tonk tearjerker, ‘Half Over You,’ from 1991’s The Rock: Stone Cold Country

MY VERY SPECIAL GUESTS

George Jones

Epic/Legacy (2005)

In its original incarnation, released in late 1979, George Jones’ My Very Special Guests was a likable and modest 10-cut LP of duets that dared to cross musical and cultural boundaries on a couple of occasions, as when Elvis Costello, in his earliest flirtation with country music, sits in on “Stranger In the House,” and Pop and Mavis Staples bring some Memphis funk to the gospel fervor of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” In this expanded, double-CD set, 27 more duets, recorded between the late ’70s and late ’90s, some for Jones projects, others being culled from other artists’ albums to which Jones lent his honky tonk heart, the original album’s admirable qualities are recast in riveting and exhilarating fashion. With partners on the order of Merle Haggard, Ray Charles, Loretta Lynn, Johnny Cash (a thumping version of “I Got Stripes” from the Man in Black’s Silver album), Buck Owens, Shelby Lynne, Alan Jackson, Vince Gill, Willie Nelson, Patty Loveless, and Patti Page, among others, with most (not all) of the cuts produced by Billy Sherrill, who always got the best out of Possum’s way with a song, it becomes impossible to single out only a few highlights–the performances are that good, not only in their musical conception, but in the vocal execution. Jones pours his heart into every note he sings, to the point where his partners in song are almost diminished by comparison. But B.B. King gives a monumental reading of the Clarence Carter classic, “Patches,” for which producer Don Was fashions a big, booming production that allows B.B. room for a pungent solo to boot, on a tune where Jones is clearly along for the ride. A keening, moaning take of a Jones standard, “A Good Year for the Roses,” brings out the best in George as well as Alan Jackson in a true vocal tour de force mating of two great country singers. In short, it takes a lot to keep up with the Jones here, and that reality spurs some other good artists to bring their A game to this most impressive reimagined reissue. –David McGee

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MzQrAPoTI58

From the album My Very Special Guests, a live version of the Jones classic, ‘A Good Year for the Roses,’ with Alan Jackson

KICKIN’ OUT THE FOOTLIGHTS…AGAIN

George Jones & Merle Haggard

Bandit (2006)

At the time of this 2006 release a quarter century had passed since Merle Haggard and George Jones last cut an album together, but on their reunion project (bearing a title that more than hints at their once rough-and-rowdy ways) they slipped into each other’s rhythms and mindsets with an ease that illustrates the kinship between Possum’s Texas-style honky tonk and Merle’s tradition-rooted Bakersfield sound. The loose concept here is each artist covering the other’s tunes–so you get Merle offering up a smooth, gentle shuffle treatment of Jones’s devastating study in ironic heartbreak, “She Thinks I Still Care,” and Jones rendering Hag’s shattering final testament from a Death Row inmate, “Sing Me Back Home,” with a piercing, hymn-like solemnity that heightens the horror of the moment without resorting to melodrama. Hag returns the favor with some subdued honky tonk crooning on Jones’s wrenching account of marriage on the rocks, “The Window Up Above,” and Possum checks in on Hag’s own reaction to his woman’s faithlessness, “All My Friends Are Strangers,” its sprightly, honky tonk arrangement and cool vocal both in stark contrast to the muted rage the lyrics suggest. Naturally these two have a good time paying homage to that country music staple, the drinkin’ song–with a sly wink of a vocal—because who knows a drinkin’ song better than Possum?–Jones works his way through the thumping kissoff, “I Think I’ll Just Stay Here and Drink,” and the two artists join voices on a delightful, semi-autobiographical western swing workout, “Sick, Sober & Sorry,” an uptempo winner further graced by an exuberant piano solo from another venerable country artist, Hargus “Pig” Robbins. A nice closing touch comes by way of the lilting, Bob Wills-style pop shuffle arrangement of Duke Ellington’s “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” its warm vocals supported by some engaging mid-song banter between two old pros musing on follies of yore. As an exercise in real country and treasured friendship, Kickin’ Out the Footlights…Again is as good as it gets. –David McGee

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3HtcnR6H73s

From 2006’s Kickin’ Out the Footlights…Again, George and Merle offer a cool, gently swinging take on Duke Ellington’s ‘Don’t Get Around Much Anymore’

A PICTURE OF ME (WITHOUT YOU) [1972]/NOTHING EVER HURT ME (HALF AS BAD AS LOSING YOU) [1973]

George Jones

American Beat Records (2009)

One of the real joys of reissues is that fact that they can compel you to start re-thinking about music that you thought you already knew pretty well–only to find out that the prism of time may make you appreciate it in a new light. That’s certainly the case with these two early ’70s George Jones albums which, while repackaged together in a single CD sporting no frills (no bonus or unreleased tracks, and threadbare discographical data), nonetheless offers solid value in terms of both re-highlighting excellent original work and the underlying subtext of what went into them.

While history correctly posits George Jones as one of country music’s greatest and most enduring figures, the George Jones who signed with Epic Records in 1971 was joining a label where his wife, Tammy Wynette, was at the time actually the bigger selling star. That was due in no small part to the work of producer Billy Sherrill, whose think-outside-the-fence approach to the sound of country music in the late 1960s had helped catapult Wynette to the top of the charts.

A live version of ‘A Picture of Me (Without You),’ the title track of Jones’ 1970 album, which peaked at #3 country

It is always significant to note that Sherrill, whose resume included early engineering work for Sun Records’ legendary Sam Phillips as well as rock and gospel acts at the start of his producing career at Epic, was generally regarded as an outsider throughout his time as a Nashville hitmaker, and often looked down upon by the country music establishment for what was deemed too much of a lush, pop-leaning sound. (The joke, of course, is that Sherrill, like any good producer, guided the artists and material he was working with to maximum effect, as attested by his crossover pop successes with a diverse set of performers ranging from Wynette and Tanya Tucker to Charlie Rich and Johnny Paycheck.)

‘You’re Looking at a Happy Man,’ the ‘White Lightnin’’-like cut from the 1973 album, Nothing Ever Hurt Me (Half as Bad as Losing You) (#12 country)

In any event, it is interesting to listen in 2009 to these albums, originally released in 1970 and 1973–two of the first of the decade-plus relationship between singer Jones and producer Sherrill–and appreciate how truly conventional they are in terms of the bedrock spirit of country music coming through, in both the songs themselves and in Jones’ ever-masterful singing. A Picture Of Me (Without You) is almost exclusively ballads, and is highlighted by classic compositions like Norro Wilson’s title track (“Imagine a world where no music was playing/Then think of a church with nobody praying”), Tom T. Hall’s “Second Handed Flowers,” and Ernest Tubb’s “Tomorrow Never Comes.” Meanwhile, 1973’s Nothing Ever Hurt Me (Half as Bad as Losing You) features numerous uptempo tunes like the novelty-styled title track (“My best friend set my barn on fire and burned my horses to death/I went out with a girl who told me, ‘George you got bad breath'”) and the “White Lightnin'”-like “You’re Looking At A Happy Man,” while also nodding towards tradition with a fine reading of Lefty Frizzell’s “Mom And Dad Waltz.”

What isn’t as conventional, though, is Sherrill’s production style, which often juxtaposes twangy guitar tones and bass lines borne in ’50s rockabilly with the sweetening sounds of harmony-laden backing vocal ensembles. That combination of rough and smooth textures was key to the Sherrill sound, and for Jones, who turned 40 in 1971, it provided a landscape that allowed him to progressively dig deeper into his own daunting well of emotions, and in the process truly mature as a singer and interpreter. You can sense that process beginning to unfold on these two albums, and what a treat it is to go back and re-trace it after all this time. –Billy Altman

About Dean Tomasek: Dean Tomasek was born in Chicago, Illinois and spent his childhood in Arizona, Colorado, and Wyoming, before moving to Nashville, Tennessee on his eighteenth birthday. His passion for art and music was evident at an early age, and also fueled his adult life, as he played bass and painted anything to make ends meet. He designed and painted signs, airbrushed jackets, did faux finishing, murals, stage sets, album covers and posters, as well as creating his own artworks. “My art is simple and direct,” Dean states. “I paint mainly from photographs, and I painstakingly try to bring out the true essence of the subject. If it’s a musician I’m painting I will listen to that artist obsessively, read interviews, and look at dozens of photos. By the time the piece is finished, I’m pretty much an expert on that subject.” Music City has embraced Dean as being one of the most promising up-and-coming artists in a highly competitive community. His artwork resides in many living rooms, recording studios, bars, hotels, and restaurants, as well as being featured in various Nashville art galleries. This commissioned portrait of George Jones and other works by the artist—Nature, Portraits, Posters, Design, Woodworks—are available at his website, www.deantomasek.com

.