Of the untold number of poems inspired by the story of Jesus’ resurrection, none have engendered as much speculation, interpretation and consideration as to its greater meaning than John Updike’s ‘Seven Stanzas at Easter.’ In marking Easter and the Pentecost in Deep Roots, we offer the Updike poem; the story of its discovery in 1960 when the young poet entered it in a Massachusetts church’s Religious Arts Festival and won a $100 prize for “Best of Show”; and, in ‘Seven Voices on ‘Seven Stanzas,’ seven perspectives, from lay people and clergy alike, reflecting on their personal experience with Updike’s poem and what one distinguished cleric reads as a call for Easter not be ‘trivialized, reduced to a happy ending or a pious parable.’

Seven Stanzas at Easter

By John Updike

(from Telephone Poles and Other Poems, 1963)

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

It was as His body;

If the cell’s dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

It was not as the flowers,

Each soft Spring recurrent;

It was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled

eyes of the eleven apostles;

It was as His flesh; ours.

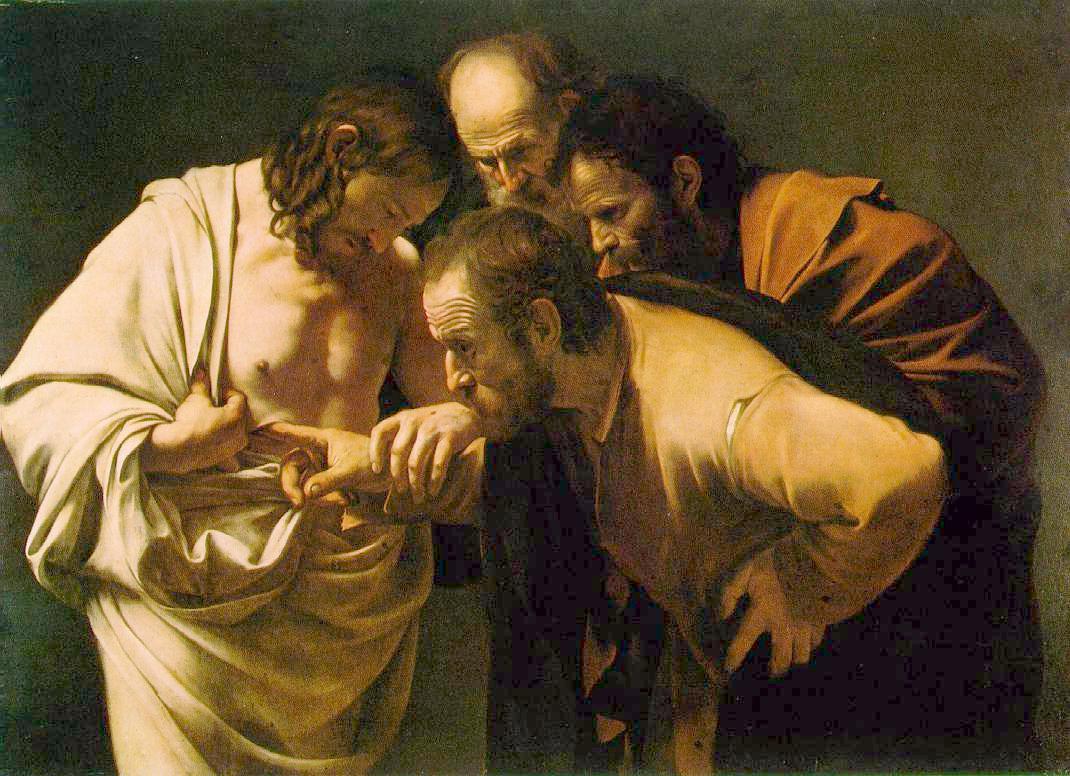

The same hinged thumbs and toes

The same valved heart

That-pierced-died, withered, paused, and then

Regathered out of enduring Might

New strength to enclose.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence;

Making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

Faded credulity of earlier ages:

Let us walk through the door.

The stone is rolled back, not papier-maché,

Not a stone in a story,

But the vast rock of materiality that in the slow

grinding of time will eclipse for each of us

The wide light of day.

And if we have an angel at the tomb,

Make it a real angel,

Weighty with Max Planck’s quanta, vivid with hair,

Opaque in the dawn light, robed in real linen

Spun on a definite loom.

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,

For our own convenience, our own sense of beauty,

Lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour, we are

Embarrassed by the miracle,

And crushed by remonstrance.

The Story Behind ‘Seven Stanzas’

By Kathleen Kastilahn

April 2001

Norman D. Kretzmann remembers John Updike as a young Harvard graduate who sought out Clifton Lutheran Church in Marblehead, Mass., because it “nurtured the roots of faith he had grown up with in Pennsylvania.”

Kretzmann, pastor of Marblehead at the time, proudly recalls that Updike was among the 96 adults who entered the congregation’s Religious Arts Festival in 1960–and that his poem, “Seven Stanzas at Easter,” won $100 for “Best of Show.”

“People in the parishes I served became quite accustomed to my quoting his poem in my Easter sermons at least every few years,” says Kretzmann, who lives in a Minneapolis retirement center and regularly contributes to the Metro Lutheran newspaper.

Kretzmann closely follows Updike’s work, which includes more than 50 novels and books of poems. In a Metro Lutheran review of John Updike and Religion (Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2000) he wrote: “I was John Updike’s pastor during the time which the writer later described as his ‘angst-besmogged period.’ Who was the rabbi and who was the disciple of our years together is hard to say.”

The pastor still has Updike’s 41-year-old typed copy of “Seven Stanzas”–“marked up with all sorts of irrelevant notes by me, instructions to me for homiletical purposes or for various secretaries,” he said. And Kretzmann has one more fond memory from the festival: Updike gave the $100 prize back to the congregation.

From The Lutheran.org

SEVEN VOICES ON ‘SEVEN STANZAS’

I

‘Let Us Step Into That Reality!’

In the Faith Connections class last Sunday (3/25), we continued our discussion of resurrection from 1 Corinthians 15. Specifically, we considered Paul’s teaching in 1 Cor 15:20-34 that Christ’s resurrection is a doorway to humanity’s re-creation. His salvation and redemption are not limited or restricted to the spiritual (how can they be?), but include the physical and everything else. Jesus’ rising from the dead also began a chain of events by which all that opposes God—including death—will be brought under His sovereign authority.

Christ’s bodily resurrection is the beginning of so much that follows—including a new way of living. Because Christ rose, we will rise also, so we can live for more than today. How can our lives today reflect this? How can we be a sign of what is coming, the kingdom of God where all is set right at his feet? As John Updike puts it in his poem “Seven Stanzas at Easter,” because Jesus physically rose (not metaphorically), there is a real door through which we can walk. Let us step into that reality!

–Posted by John H at Faith Connections, March 27

II

An Easter Reflection

By Anna Blanch

‘…my heart and soul wanted to avoid contemplating the depths of Christ’s suffering. It just seems too hard and too much right now. I’m not ready. I feel overwhelmed by life.

I’m tired. Actually, I’m exhausted: physically, emotionally, mentally. I’m even a little tired spiritually. It has been a rough few months. I’m still grieving the loss of my grandmother. I’m definitely in the hard yards phase of the second year of my doctoral thesis writing experience. My body is responding badly to the inherent stresses of life. And it was a long, cold, and dark winter in Scotland. Easter has been a distant light casting off a hopeful glow at least since the beginning of Lent. The joy of the Springtime flowers, the glimpses of warming sunlight, and the words of Madeline L’Engle, Katherine Norris, Wendell Berry, and the Psalms have been a balm to a battle-torn soul.

I’ve been looking forward to the triumphant joy of Easter Sunday–the sharing of a wonderful meal in the company of friends and fellowship as we hail the coming of the King. As I contemplated the form of this Easter reflection, I realized that my heart and soul wanted to avoid contemplating the depths of Christ’s suffering. It just seems too hard and too much right now. I’m not ready. I feel overwhelmed by life. The Passion seemed, (I admit, still seems) too brutal and difficult for me to meditate upon. It seemed somehow easier, though only heaven knows why, to think upon the marvelous mystery and miracle of the Resurrection–to declare the reign of a King whom I worship as Lord and Savior–than to set my eyes upon the events that lead up to Easter Sunday. Though finding a positive uplifting message is often what we’re encouraged to do in times of struggle and weariness, is that what Easter is really about?

I’d like to suggest that it’s not, at least not totally. I want to reflect briefly on two verses from John Updike’s “Seven Stanzas at Easter” which have provided a sobering foil to my self-absorption.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

analogy, sidestepping transcendence;

making of the event a parable, a thing painted in the faded credulity

of earlier ages:

let us walk through the door.

Let us not make it less monstrous,

for in our own convenience, our own sense of beauty,

lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour,

we are embarrassed by the miracle,

and crushed by remonstrance.

It may be easy on one’s battle weary heart, and it may satisfy us to think only of the happy, sweet, pretty picture. But I wonder whether in limiting ourselves to the PG version how much we miss the wonder and power and mystery of the Passion. I wonder whether we are like those Jews who thought the Messiah would come as the conquering King, all powerful to usher in a new Kingdom. Of course, he did that, but not in the expected way. Does it spontaneously solve all that ails me in realizing this? No, but my perspective has been realigned, whether I like it or not. The King is coming, the least I can do is have an open heart.

Posted on March 4, 2011 at Transpositions

About the Author: Anna Blanch

Australian-born writer, arts critic, and photographer Anna Blanch cares about thoughtful engagement with arts and culture. In addition to her own website, Goannatree; being one of the founding contributors of Transpositions–a collaborative project on Theology, Imagination, and the Arts–and a columnist for The BIGBible Project’s #Digidisciple project, she has had scholarly and freelance articles published in a wide range of publications. Anna is in her final year of a PhD at the Institute of Theology, Imagination and the Arts at the University of St Andrews, Scotland. Photo: Gill Gamble.

III

‘Without the Resurrection, Jesus Was Just Another Wise Teacher…

PASTOR’S PONDERINGS, MARCH 2011

Rev. Dr. Bradley J. Donahue

The celebration of Easter is as late as can be on the calendar so we have a better chance this year of warm weather for Easter Sunday. Likewise Lent starts later so we have spent more time in the church season of Epiphany then we usually do.

Both occurrences can be a little unsettling for us, we are not use to such lateness in the church calendar. We usually move through the seasons fairly quickly. But not this year, this year Easter will take its own sweet time coming.

Church historian tells us the in the early church Easter not the celebration of Christ’s birth was the most important holiday. The early church was slow in recognizing the celebration of Christmas. There is some theological soundness in this. I love Christmas but what is most significant to the faith is that God worked a marvelous miracle on Easter morning.

Without the resurrection, Jesus was just another wise teacher, who taught some very important things.

What sets him apart from all others is the proclamation of the angel, “He is not here. He is risen.”

American author John Updike in his poem, “Seven Stanzas at Easter” writes:

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

It was as His body;

If the cell’s dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

Maybe Updike has a point, maybe we don’t take the power of the resurrection seriously enough.

It was the event that drove the early church and empowered them to proclaim the good news.

As we enter Lent perhaps this would be a good time to reflect on what the Resurrection means for us.

1 Cor 15:14-17:

…and if Christ has not been raised, then our proclamation has been in vain and your faith has been in vain. We are even found to be misrepresenting God, because we testified of God that he raised Christ-whom he did not raise if it is true that the dead are not raised. For if the dead are not raised, then Christ has not been raised. If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins.

Grace and Peace,

Dr. Bradley J. Donahue

VOLUME 1, ISSUE 3

TEMPLE TALK

Originally posted at the website of Lorain Christian Temple Disciples of Christ, Lorain, OH

(Photo courtesy FreeFoto.com http://www.freefoto.com/download/05-27-2/I-am-the-resurrection-and-the-life)

IV

‘Uncompromisingly Biblical’

By Tom Grosh IV

When considering the correspondence theory of truth in Christianity and Literature: Philosophical Foundations and Critical Practice (Christian Worldview Integration Series. InterVarsity Press. 2011), David Lyle Jeffrey and Gregory Maillet refer to John Updike’s “Seven Stanzas at Easter” (1960). *Enjoy this excerpt from a “bold, wonderfully learned manifesto … [which] breathes a prophetic passion — bracing, salutary and sometimes uncomfortable — that transcends mere academic discussion and leaves the reader interrogated as well as taught.” (Dennis Danielson, Professor of English, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and editor of The Cambridge Companion to Milton. at InterVarsity Press.)

Historically, the predominant way of looking at truth is the one that occurs first to common sense. According to the correspondence theory of truth, a verbal claim is true only if it corresponds to pertinent fact or external reality.20 If there is no correspondence (e.g., if I claim that the sky is falling and some of my students run outside to check and confirm, sensibly, this it is not), the claim is evidently false at the literal level. On this view, if a speaker or writer claims that the earth is flat or that it will come to a catastrophic end in Y2K (A.D. 200) or that drinking a certain beverage will make us irresistible to the opposite sex, there are ways to investigate the veracity of each claim.

Even when we account for variance in the way people see things, this theory tends to apply to most situations quite serviceably. In each case of this sort, actuality (or as we might say, reality) takes precedence and is indispensable to the claims made regarding it, as well as the plausibility of inferences that may be drawn or actions recommended in consequence. In a famous example from the New Testament, St. Paul insists that if Christ did not literally rise from the dead, then all discussions of the event and our faith in it are meaningless and a waste of time (1 Cor 15:12-20). The poetic commentary of John Updike in his “Seven Stanzas at Easter” (1960) is thus historically and logically on the mark when he says

if he rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle

the Church will fall.

Updike is in this poem uncompromisingly biblical in his insistence on a correspondence theory of truth; no soft metaphorizing of the resurrection, given the explicit factual claims of Scripture and the church, can be other than a lie –especially if created, as Updike says, “for our own convenience, our own sense of beauty.” Updike was in this poem reacting to common liberal theological platitudes and, in the fashion recommended by Paul to Titus, giving such revisionary constructions a stiff rebuke. To turn the essential truth given in historical event into an evasive and naturalistic trope is here to pervert the proper business even of poetry, especially for the poet who wants to think like a Christian.

About Tom Grosh IV: Enjoys daily conversations regarding living out the Biblical Story with his wife Theresa, four girls, around the block, at Elizabethtown Brethren in Christ Church, on campus as part of InterVarsity’s Graduate & Faculty Ministry, in the culture at large, and in God’s creation. More posts by Tom Grosh IV are online at Emerging Scholars Blog.

V

‘A Resuscitation View of The Resurrection’

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

It was as His body;

If the cell’s dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

It was not as the flowers,

Each soft Spring recurrent;

It was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled

eyes of the eleven apostles;

It was as His flesh; ours.

These are two of John Updike’s seven “stanzas at Easter,” famous for their rigorously material way of representing the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Of course the poem is just that–a poem, not a theological treatise in disguise. That being conceded, it is nevertheless interesting to see what it aims at theologically. Clearly, the poem voices a resuscitation view of the resurrection that may strike us as crude, highly disturbing and even offensive. Where in the New Testament do we find the resurrection depicted in such a vividly realistic way as in the first of these stanzas? Clearly, the New Testament reports are consistent in not portraying the resurrection as a kind of reversal of natural biochemical processes, but as a transformation into a new kind of existence, characterized by a physicality that displays both continuity and discontinuity with our present physicality. At the same time, however, we intuitively feel that Updike has a point. If we are to think about the resurrection with integrity, we cannot escape thinking about it in its concrete materiality. For clearly, sheer analogy and parable can hardly bear the weight of real hope which springs from the resurrection stories.

But can we still subscribe to such a “realist” view of the resurrection, given the host of old and new objections that have been and are being put forward against it? Or to put this question in a more open way: can we speak with intellectual and theological integrity on the resurrection of Christ today, and if so how?

From “How to speak with intellectual and theological decency on the resurrection of Christ?: A comparison of Swinburne and Wright,” by Gijsbert van den Brink

Faculty of Theology, VU University Amsterdam, Netherlands; from the Scottish Journal of Theology, 2008.

VI

On Easter and Updike

by David E. Anderson

(excerpt from the longer essay, “On Easter and Updike,” published April 7, 2009, at Religion & Ethics Newsweekly)

Easter is not easy for most poets and writers, the difficult mystery of resurrection being more intractable than incarnation.

One of the best examples of the problem is perhaps the most famous Easter poem of the second half of the 20th century, John Updike’s “Seven Stanzas at Easter.” Updike identifies the difficulty in the opening line:

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

The crucial word in the center of the first line—if—states what might be called “the Easter problem” starkly, and Updike’s insistence on the orthodox doctrine of the physical, bodily reality of the resurrection, even when hedged with the doubting if, provides a succinct but apt statement of one of the key themes of his work—the terror of death and the search for some sense, some promise, of overcoming, and he will not brook any evasions:

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

analogy, sidestepping, transcendence,

making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the faded

credulity of earlier ages:

let us walk through the door.

The tension between belief and doubt in the face of death, between faith and its opposite—certainty, and the need for resurrection run through all of Updike’s vast body of writing, from his early novels, stories, and poetry (“Seven Stanzas at Easter” was written in 1960, just a year after his first novel was published, and the poem was the winning entry in a religious arts festival sponsored by a Lutheran church on Boston’s North Shore) to his later work, including Due Considerations, his final collection of essays and criticism, and Endpoint, a posthumous book of poems published [in April 2009].

…

Still, it must be noted that despite Updike’s insistence that if Jesus rose it was a bodily rather than metaphorical resurrection, Jesus himself and the events surrounding the crucifixion and resurrection are largely absent from his poetry and fiction. His hope, the unstated Easter hope for eternal life that runs through his work, is dependent on what he called in one story “supernatural mail” with its “decisive but illegible” signatures, those very immanent things and events that contain within them the promise of more. In “Pigeon Feathers” he provided a telling example: “The sermon topics posted outside churches, the flip, hurried pieties of disc jockeys, the cartoons in magazines showing angels or devils—on such scraps he kept alive the possibility of hope.”

Or as Updike affirmed in the last line of the first poem in his final book: “Birthday, death day—what day is not both?”

David E. Anderson, senior editor at Religion News Service, has also written for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly.

VII

‘What Door Now Stands Open?’

excerpt from Easter Day Sermon 2004

by the Bishop of Meath and Kildare,

the Most Revd Dr. Richard Clarke

at St. Brigid’s Cathedral, Kildare, Easter Day, 11 April 2004

Revelation 3.8 “I have set before you an open door which no one can shut.”

The Gospels are of course certainly talking about the Resurrection as a real event, an event in human history. There is, as we know, a condescending and superior approach to the whole matter which suggests that the Gospel writers were speaking of a symbolic resurrection, that Jesus remained very much dead, and that what we call Easter was merely a realization on the part of the disciples that this man Jesus Christ was possibly on the right lines after all. His resurrection was in their heads and in their imagination, but nowhere else. This is, it seems to me, staggeringly patronizing–patronizing about the Gospel writers who would have known perfectly well how to make it clear if they were writing metaphor, patronizing about generation upon generation of great Christian thinkers and writers who were in fact not gullible idiots, patronizing about us who don’t like to think of ourselves either as fools or as fantasists. It’s actually patronizing about God as well. As the American writer and poet John Updike puts it so neatly, in one of his Seven Stanzas at Easter,

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

analogy, sidestepping transcendence;

making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

faded credulity of earlier ages;

let us walk through the door.

The question accordingly becomes a matter, not only of the objective reality of Resurrection, but also of the impact on the lives of disciples. disciples of the twenty-first century as of the first century–of how disciples walk through this door of which both the writer of the Book of Revelation and John Updike speak to us. The question becomes, “What effect does the resurrection of Jesus Christ have on our lives?” “What door now stands open?”

*The Resurrection means first that, as individuals, we must look at Christ in a different way. Mary Magdalene, who had loved and admired him before, now finds herself utterly transformed by him. She becomes different, because everything falls into place. All that he had said and had done were no longer the words and actions of a good man, even the best man there had ever been, it had all been given an eternal reality for her which could not be contradicted or ever destroyed. No matter how often we are told that it will not do to patronize Christ, and to treat him as an amiable carpenter with a good line in stories (who would however not have survived for very long in any real grown-up world), we still do it. The resurrection is the playing of the trump card which tells us that if we not treat him with the utmost seriousness and with total reverence, it is we who are the buffoons.

*It means also that we cannot look at others in the same way. Most of the resurrection stories are stories of Christ’s friends meeting together–in a room, in a boat, on a beach, walking to a village. The Easter event is about sharing faith, being part of a community which celebrates the presence of Jesus Christ. We are pushed again and again in the Easter stories to realize that Christ is real and present with us in the Eucharist, the meal of the Church, as he shares food in a village room, as he asks for food on a shore, as he eats with his disciples in a room in Jerusalem. The risen Christ joins with his followers as they meet together. This is why it is so immensely foolish to imagine that we are somehow doing God a favor when we turn up in church for a service. Worship should never be seen as anything other than an immense privilege to be treated with the greatest humility and reverence, as the God who created us, who keeps us in being and who has smashed through the dreadfulness of death ahead of us, is ready to join us as companion and friend. Christian worship, Christian community and Christian fellowship become Easter gifts to be prized and revered, and for which we should be ever and profoundly thankful to God.

*It means that we can face ourselves in a new way. What are we as individuals without the resurrection? A moderately sophisticated organism which, simply because it has a thing called a “mind,” gets ideas far above its station, but which nevertheless ceases to exist after a few brief spins of a grubby little planet around the nearest, rather insignificant star. It is God in Christ, God in the risen Christ, who gives us a real dignity and a true purpose. This is not the bogus dignity we so readily give ourselves. This is the dignity of being a child of God, given a function and given a purpose to bring others into loving fellowship with him. I have no doubts that the value of our earthly life will be measured in the context of eternity, neither by how much we accumulated for ourselves, nor by how much others feared us or envied us, but by how much more Christian this world became, because we lived in it. And this conviction, if you think about it, only makes any sense in the light of Easter.

Easter is of course far, far more than a good reason for being a Christian. This is why we must never trivialize it, or reduce it to a happy ending or a pious parable. It is an open door to faith, to hope, to love, and thus to the fullness of eternal life.

“I have set before you an open door which no one can shut.”

Published at Diocesan News-Church of Ireland