For me, the only really important question to ask when studying a biblical story is ‘what can I learn from this that makes me a better person who is a more worthy partner in my covenant with God?’

When it comes to Passover, there is good news and bad news. The good news is that more Jews will celebrate some sort of Passover Seder than will engage in any other sort of Jewish religious or cultural activity all through the year. The bad news is that often these seders are merely gatherings of friends or family with scant attention paid to the ritual or message of the festival.

That is a pity because the story of our liberation from Egypt is the enabling event of all subsequent Jewish history. People often ask, “Is it true?” Were we really enslaved, and did the sea really part for us to be free? In truth, I do not know. For me, though, the only really important question to ask when studying a biblical story is “what can I learn from this that makes me a better person who is a more worthy partner in my covenant with God?”

With that question in mind, the Exodus becomes our people’s most important story. Indeed, there are only two events that we recall in every morning and evening service. They are the creation of the world and the Exodus from Egypt. When we sing the Kiddush each Friday night we mention, once again, only two biblical events: the Creation and the Exodus.

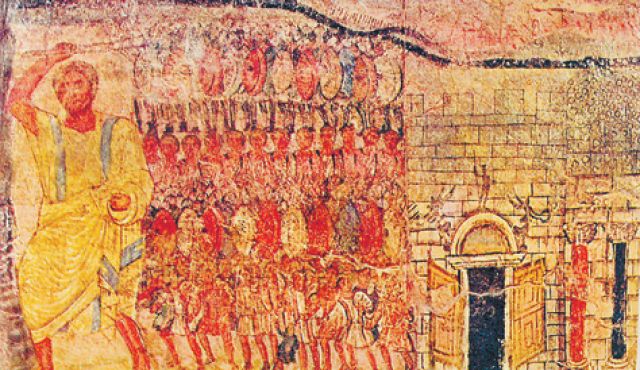

The Exodus story is really a war between gods with diametrically opposed value systems. On one hand, there is the Egyptian god Pharaoh. The only purpose of Egyptian worship was to build bigger and bigger monuments to glorify the god Pharaoh. If you need slaves to do that, fine. If you had to beat the slaves to make them work harder or even kill slaves to send message to other slaves, that was fine too. And if the slaves threatened to grow too much, it was just fine to throw baby boys into the River Nile to either drown or become food for the crocodiles.

On the other hand, there is the one true God. The very best way to worship our God is to use our talents and abilities to make this world a better place. To worship our God is to care for the poor and elderly, to welcome the stranger and treat everyone with dignity and respect. Could the way we worship God be any more different than the way people worshipped Pharaoh?

The Exodus from Egypt and Journey to Kadesh-barnea: ‘The point of the story is that God got us out of there and as a result we owe God a debt we can never fully repay.’

The story of the Exodus is the story of our God going to war against the god Pharaoh who had enslaved us. We were lost in Egypt. Our lives were a hopeless humdrum tedium of finding straw, making it into bricks, and building monuments and storehouses for Pharaoh.

The point of the story–and the festival that we have made out of it–is that God got us out of there and as a result we owe God a debt we can never fully repay. Imagine for a moment something none of us wants to imagine. Your small child is playing on the porch, and something distracts you. Before you realize it, your child has wandered into the street and a truck is heading toward him. You realize with horror that there is no way you can get there in time. Just at the last instant, though, a stranger runs into the street, swoops up your child and brings him safely out of danger.

No matter what you might offer the stranger, you can never adequately repay her for what she has done for you. That is the message of Passover: God saved us, and there is no way we can ever adequately repay the Almighty for allowing us to live lives of meaning and purpose instead of lives of endless onerous labor for Pharaoh.

The message, though, is that we must try. In accepting our freedom from Egypt we, hopefully, bind ourselves to serving the Eternal One, and we serve the Almighty best by trying to make the world a better place.

This year, as we gather with family and friends, hopefully we resolve to work for the day when all people everywhere are free of Pharaoh-like bondage and able to practice their religion freely. Hopefully, as we sit down to our Sedarim this year, we shall also think of how we can make it easier for Progressive Jews around the world to learn about our heritage, and in so doing to connect with each other, with the land of Israel and perhaps most significantly with us.

Rabbi Stephen Lewis Fuchs is president of the World Union for Progressive Judaism. This essay was first published in WUPJ News #433, 29 March 2012.