Devon Allman: ‘twenty years from now I hope I’m still kickin’ around/I wouldn’t change a thing/because I’ve gotten here now…

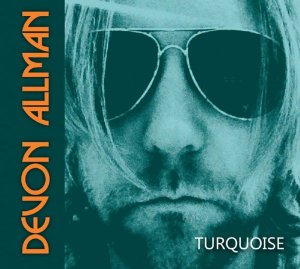

TURQUOISE

Devon Allman

Ruf Records

The surname is oh-so-familiar, and will doubtless cause some to wince at the thought of yet another offspring of the famous entering the same field as those who brought him into this world and proving to have lesser gifts than his parent(s). In the case of Devon Allman, those concerns are unfounded. Certain attributes must be born in the blood—an unerring feel for country blues, a certain rocking spirit, and a taste for messing with conventional approaches that expand tradition while simultaneously embracing it. Right here it should be noted that he did not even meet his father until he was in his teens. An instant bond formed, but it’s not like he spent his childhood following Gregg around, which may account (or maybe not) for some insinuations of Gregg’s roots in Devon’s music, but the end result being an artist claiming his own turf while not disowning his celebrated surname.

Allman’s own notes to his solo debut—we have previously heard and been impressed by his artistry in last year’s acclaimed Royal Southern Brotherhood alliance and he has recorded two interesting albums billed as band efforts, Devon Allman’s Honeytribe (2010’s Space Age Blues and 2006’s Torch)—say something about the path that has brought him to the point of bringing his own music to a wider audience, a path marked by a wandering troubadour’s highs and lows. The first song, in fact, is titled “When I Left Home,” and its place in the sequence surely is no accident. “I wanted a song that really encapsulated my last 20 years,” he writes. “I left home at 17 to work on music, and the day I decided to split I was in NYC that evening.” Of another tellingly titled number, “Homesick,” he reveals: “The last 12 years I’ve spent in hotels, airplanes, taxis, truckstops, etc. This song is dedicated to my family for putting up with my absence. Know that you are in my heart with every mile I travel and every mile we spend apart.” Of “Into the Darknes,” he writes: On March 17, 2000, my life changed forever, for the better, as my son was brought into this world. Orion, my son, the lyrics have bounced around in my head since you were just a tiny thang. This one’s for you” Of a song inspired by his girlfriend, “Yadira’s Lullaby,” he recalls using Skype to say goodnight to her when they were apart “and I would play this 3 string cigar box guitar to serenade her to sleep.” And of the album’s final song, the end of the journey that began with “When I Left Home,” Allman returns to the fold in “Turn Off the World,” in a manner of speaking, in confessing to a post-vacation epiphany: “I realized how important it is to slow it all down and really recharge my batteries. Truly good for the soul.”

Devon Allman, ‘Strategy,’ from Turquoise

But beyond establishing an artist’s literacy, intriguing liner notes are hardly the measure of an album’s worth. Is the music there? Are the arrangements solid, or even daring? Is the singing authoritative and commanding? Does it approach, or elevate, to a point of transcendence, where shortcomings become strengths and the listener is transported by the artist’s all-consuming commitment to his art and message?

The answer to every one of these questions is a resounding yes. You know so immediately, from the magnitude of Yonrico Scott’s thundering percussion and the wail of Luther Dickinson’s slide guitar introducing “When I Get Home,” the album’s first track, a feeling that intensifies when Allman enters and sings of a 20-year odyssey to find his place in the music world (here he speaks of the famous family legacy and fears he would “never amount to much or be the talk of the town”) but also of an undaunted spirit. After two decades of chasing the dream, his hope is “twenty years from now I hope I’m still kickin’ around/I wouldn’t change a thing/because I’ve gotten here now…” Dickinson’s slide is searing, the track’s drive packs a punch, has a certain urgency about it; and Allmans’ voice is not that of his dad’s but, significantly, his own: strong, emotional, honest, authoritative, not as blues-drenched as father Gregg’s but every bit as deep in feeling. You know something’s special afoot in the unfolding majesty of the album’s second cut, “Don’t Set Me Free” (co-written by Allman with his Royal Southern Brotherhood mate (and contemporary blues master Mike Zito), a soul shaking maelstrom comprised of Allman’s blazing guitar, Scott’s muscular drumming and the thick, resonant hum of Rick Steff’s church-like B3 setting up Allman’s soulful plea to a lost love who “don’t give a damn for me,” in an arrangement featuring the lead vocal shadowed by a backing vocal quartet (which includes his Ruf labelmate Samantha Fish, whose own career got off to a laudable start with her 2011 debut—see an in-depth profile of her in the September 2011 issue of TheBluegrassSpecial.com) in a bluesy version of gospel’s call-and-response approach, which builds tension incrementally until Allman’s final, broken-hearted “don’t set me free” sounds an unsettling finale to a hopeless situation.

Devon Allman, ‘Homesick,’ from Turquoise, live at Sellersville Theatre, Sellersville, PA, December 27, 2012

“Time Machine” illustrates how the son has learned a few lessons from the father when it comes to blues balladry and blues ballad writing. Soft and languorous with a slinky groove courtesy Scott’s percussion and Allman’s shimmering guitar, the song reflects on the rapidity of the years passing by, from a childhood spent playing outside “until the sun disappeared behind the tall trees and time evaporates on the breeze” to that “first kiss in the night/innocence was lost deep inside…time moved by slower it seems.” Because his point is to embrace life rather than to mourn its fleetingness—“good times come, good times go, bad times roll in and out like a storm…all aboard the time machine”—Allman delivers his lyrics straightforwardly; cool and laid back, he counsels enjoying the ride, even when it’s tough going, rather than fixating on a destination looming ever closer on the horizon.

Devon Allman, ‘When I Left Home,’ from Turquoise, Sellersville Theater, Sellersville, PA, December 27, 2012

Devon Allman, ‘Don’t Set Me Free,’ from Turquoise, live at Sellersville Theater, Sellersville, PA, December 27, 2012

All this amounts to a strong calling card for Allman and reflects the diversified attack throughout Turquoise. “Homesick” has a funky, B3-enhanced groove and is arguably the most fully realized of the eleven tracks here, owing to the confluence of Allman’s deeply felt lyrics reflecting the title sentiment born of many, many years on the road and the rootless sense they bring, the bone-deep weariness in his vocal and not least of all his tasty guitar interjections. ‘Yarida’s Lullaby,” the song he wrote for his gal and serenaded her with on a 3-string cigar box guitar, is a bright, bracing instrumental Allman picks tenderly on an acoustic guitar with lovely tonal shadings in the softer passages and soaring spirits in more muscular interludes. It’s the perfect setup for the closing number, “Turn Off the World,” a thoughtful missive advising “slow down, turn off the world/life gets crazy, life is too short…” in an arrangement with a subtle Caribbean feel underpinned by Allman’s fingerpicked acoustic and the steady, understated shuffling percussion. As he did in “Time Machine,” Allman’s coming down again on the side of cherishing being alive right here, right now, as he did on “When I Left Home,” as he did on “Time Machine,” as he longs to do with his loved ones on “Homesick.” Very much an album about lessons learned by living life full measure, Turquoise is also about Devon Allman taking the measure of his own life and cherishing what he’s learned through ups and downs, follies and triumphs, and by being at large on the land, forging his own identity. He still has a lot of growing to do as an artist, but the younger Allman here states loud and clear, for the record, that he is his own man—more to the point, that he knows who he is as his own man. No mean feat, that.