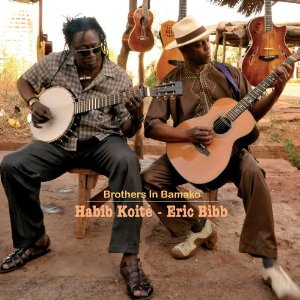

Mamadou Koné, Habib Koité and Eric Bibb: modern day griots with songs for brighter days. Photo: Thomas Loisi Min in Badische Zeitung

BROTHERS IN BAMAKO

Habib Koité & Eric Bibb

Stony Plain

Trying to describe the transatlantic meeting of souls on Habib Habib Koité’s and Eric Bibb’s summit session titled Brothers in Bamako is a bit like trying to grab mercury. It’s easy enough to say this week’s Album of the Week is magical, soulful, moving, riveting, beautiful, transcendent, but even this litany of worthy attributes comes up a little short in getting to the essence of the matter.

Its DNA is in the West African tradition of which Koité is something of an international ambassador but it’s also in the roots music Bibb–son of a musician father whose friends included Pete Seeger, Odetta and Paul Robeson (Bibb is Robeson’s godson)–was immersed in during his formative years in New York City, where he came of age just in time to experience the folk revival of the ‘50s and ‘60s in full flower. Born in Thiès, Senegal in1958 and now based in Mali, Koité is a modern-day griot, a repository of West African oral tradition and values as defined by the revered blues and architectural historian Paul Oliver (who wrote the first authoritative biography of Bessie Smith in 1959 and is a contemporary of Bibb’s father, Leon) in his 1970 book Savannah Syncopators: African Retentions in the Blues, who noted that the griot “has to know many traditional songs without error, he must also have the ability to extemporize on current events, chance incidents and the passing scene. His wit can be devastating and his knowledge of local history formidable. Although they are popularly known as ‘praise singers,’ griots may also use their vocal expertise for gossip, satire, or political comment.” Seven years Koité’s senior, Bibb was immersed in Manhattan’s folk hotbed and has brought to his own music the griot’s ability to “extemporize on current events, chance incidents and the passing scene” while never forsaking either the enduring folk, blues and gospel fundamentals he learned in his youth or the necessity of speaking up and out about the passing scene, with powerful authority, devastating wit and a deep sense of history.

Eric Bibb and Habib Koité, live at the Harmonie in Bonn, Germany, performing ‘Send Us Brighter Days’ from their album, Brothers in Bamako

So it is on Brothers in Bamako that these two gentle spirits make music on various stringed instruments (six-string banjos, seven-string guitars, eight-string ukulele, baritone guitar, acoustic nylon string guitar, electric guitar) with percussion help from Mamadou Koné and a haunting pedal steel guitar by Olli Haavisto on the duo’s hymn-like version of Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” one of only two covers among the baker’s dozen tunes. It could also be argued that theirs is more than music. Released a month after the Giving Tree Band’s provocative Vacilador (a previous Album of the Week honoree), a discourse in song on a society–a world–congratulating itself on its ability to connect via technology but seemingly incapable of sustaining personal relationships, Brothers in Bamako preaches fervently but gently for connection, with the artists themselves taking the lead by using the first two cuts to rapturously experience their arrival in each other’s worlds; it recognizes a fractured populace as an impotent populace, its divisive nature fomenting anger and intolerance instead of encouraging the embrace of each individual’s essential humanity.

Eric Bibb and Habib Koité, live at Radio 6, Nov. 2, 2012, performing ‘Touma Ni Kelen/Needed Time,’ from their album, Brothers in Bamako

Which is not to suggest these fellows have simply jumped aboard the peace train and are blissfully trundling along oblivious to the chaos surrounding them. The lilting rhythm and pillowy percussion of “We Don’t Care” are soothing, but the song itself takes dead aim at an acquisitive, amoral society, as Bibb sings assertively: We want the gold/as long as we don’t have to mine it/don’t care who suffers/or who’s behind it/we want the cool running shoes/don’t care who made them/don’t care if they go to school/or what the company paid them. The song continues in this vein, and doesn’t let up, even at the end when Bibb signs off with this pointed jibe: The gap is growing wider/between the rich and the poor/we got everything we need/but we still want more/we don’t care, we don’t care/we don’t care/do we? “Do we?” hangs in the air, the unanswered question, posited as challenge and accusation alike. As a spiritually resonant restorative, “We Don’t Care” is followed by the somber, walking blues of “Send Us Brighter Days,” in which the two mens’ voices blend in tender harmony, a lowdown, moaning guitar solo arises, and a healing prayer is offered: “Send us healin’ ways to live/help us in our hearts to forgive,” with a sparkling, hopeful grace note at the end by way of a harpsichord-like guitar glissando. Three cuts later comes the postscript to this pairing in the form of Bibb’s strutting country blues, “With My Maker I Am One,” with Bibb intoning severely, “I am the cowboy brandin’ my steers/I am the Cherokee brave on the Trail of Tears/I am the master/whip in hand/I am the slave from a distant land,” with five other verses offering similar contrasts between the haves and have-nots, the franchised and disenfranchised, the powerful and the powerless, but with a chorus featuring both artists’ voices rising in a unison, gospel-infused clarion call, “After all is said and done/with my maker I am one.” Which, after all is said and done, is kind of the point of this whole border crossing exercise.

Eric Bibb and Habib Koité, ‘On My Way to Bamako,’ live at Centralstation Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, Nov. 14, 2012. From their album, Brothers in Bamako.

Elsewhere the message are less didactic and more playfully tuneful, but not lacking serious intent in their personal reflections. The album grabs you from the first chiming, music box-like notes of “On My Way to Bamako,” Bibb’s charming shuffle about anticipating meeting up with his musical partner in Mali’s capitol. Singing deep and warm, Bibb communicates not only the joy he feels at meeting up with “a good friend there–Habib Koité” but also a rendezvous with a destiny deeper than friendship, a blood reunion: “It’s my first trip to West Africa,” he offers in a singsong lilt, like a nursery song, “but I’m pretty sure, in some kinda way”–and here his voice lowers to a prayerful tone–“it’s gonna feel like coming home.”

Koité follows in “L.A. (Los Angeles)” with his own bright, cheery reminiscence (sung in French) of arriving in Los Angeles, being met by Bibb’s family, touring around California but always being drawn back to L.A. (“I saw the sun in Salina/I also saw Macina/They all shine/but not like that of Los Angeles, L.A.”), an affection possibly explained by the catchy, upbeat chorus: “One shot, two shot, three shot, four shot/five-aahhh…tequila, tequila make me happy/Tequila, L.A. tequila time/Tequila, tequila make me happy.” Once the artists have united, they turn to the task at hand in their native tongues. In “Tourna Ni Kelen/Needed Time,” a low-key appeal to God for divine intervention–even for a moment–in a world in upheaval, with Bibb working a variation on Lightnin’ Hopkins’s themes in his gospel blues “Needed Time.” Percussive taps set the stage for the cool, understated swing of “Timbouctou,” extolling the mystical virtues of Mali’s ancient capitol city, their obvious reverence for its history now gaining added emotional impact given French and Mali troops’ recent routing of Islamist rebels from Timbuktu after they had set fire to Ahmed Baba Institute, an invaluable Islamist research center housing some 20,000 manuscripts dating back to the 14th century.

Eric Bibb and Habib Koité, ‘We Don’t Care,’ live at au Café de le Danse Paris, December 2, 2012. From their album, Brothers in Bamako.

In addition to his spare, banjo-driven interpretation of a Malian traditional tune, “Khafolé” and soothing guitar instrumental, “Nani Le,” Koité serves up “Foro Bana,” partly in his own tongue, partly in French. A brooding parable fueled by dark chords and menacing trills, it tells of a villager whose friend has promised him his daughter in marriage, with the stipulation that the villager grows fields of rice and mullet as a gift to the father. The villager meets the terms of the agreement and then some (“I even grew a field of fonio”), and now demands the father keep his word in return “and give me your daughter, my fiancé,” the trust between principled people in everyday intercourse being one of this album’s sub-themes. Which is the perfect lead-in to the duo’s weary, stark reading of “Blowin’ In the Wind,” its ambience largely shaped by a subdued, repeating banjo riff and Olli Haavisto’s quietly weeping pedal steel, with Bibb imbuing his vocal with profound sorrow, as if he and Habib were questioning their own purpose here–a feeling compounded by the album’s final tune, a sprightly, banjo-driven take on the country blues evergreen, “Going Down the Road Feelin’ Bad,” which works some variations on the Cliff Carlisle-Bill Monroe-Woody Guthrie-Grateful Dead Versions. On reflection, though, these two benedictions suggest the individual resolve to be counted. When one voice begets many, a hope rises that progress ensues.

Eric Bibb and Habib Habib Koité, ‘With My Maker I Am One,’ live at Harmonie in Bonn, Germany, November 11, 2012. From their album, Brothers in Bamako.

To those who find these brothers’ vision too old-school idealistic in an era of deep partisan rifts and rampant incivility, ponder for a moment how bracing it is to be washed in their songs of hope and conciliation. There may be better albums than Brothers in Bamako coming in 2013, but those will have to be masterpieces to be more important than this one. The key message here is found in the liner notes penned by Belgian journalist/producer/world music authority Etienne Bours, who concludes his succinct history of the artists’ coming together with a telling, indispensable insight: “Eric Bibb and Habib Koité prove with great talent that the simplest song is often the most effective and that singing as they do is a universal necessity. We need this type of encounter across national frontiers, fashions and economic dictates. Because this song is alive, authentic and profoundly human.”