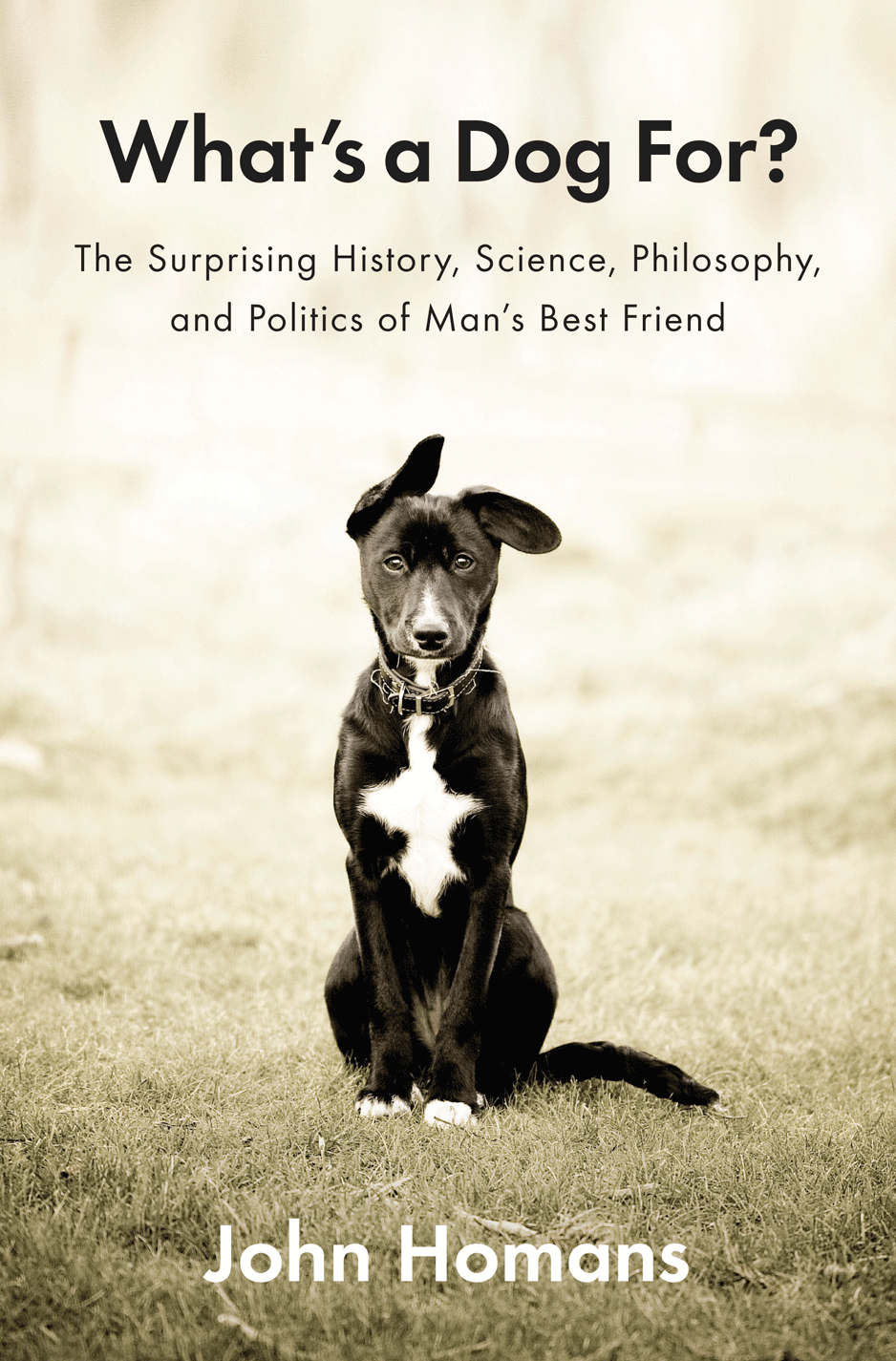

By all rights, John Homans’ new book, What’s A Dog For?: The Surprising History, Science, Philosophy, and Politics of Man’s Best Friend should be a multi-volume set that sprawls across a wide, sagging shelf.

John Homans

For his first book, Homans—the longtime executive editor of New York magazine—has embarked on an ambitious journey through the canine world, using the family Lab mix Stella as a guide dog of sorts, traversing decades (centuries, really) and multiple scientific and academic disciplines.

The subtitle doesn’t merely constitute truth-in-advertising, it may understate the case—Homans goes wide here, and he goes deep. Perhaps one of the biggest achievements of the book is the way he manages to touch on damn near everything dog-related, rendering the information with a scope and sense of detail that suggests What’s A Dog For? must surely extend across a handful of books, or at least one hulking, doorstop-sized tome.

Yet, it’s just 258 pages, including footnotes and index.

When I marvel aloud at this early in my January 30 interview with Homan on Talking Animals, he laughs and says, “That is my magazine editor’s brain, to create a lot of bite size pieces and put them all together there…the excitement of the book for me was to see how many places, how deeply and richly Stella could take me. So that was very much the point and part of the fun for me.”

Homans has served as executive editor of New York since 1994. When a man of letters—someone who’s been in the writing racket that long—finally decides to undertake his first book, I’m often curious about what prompted him to do so. (Maybe more so if it’s an animal book.)

“It actually had it’s beginning as a New York magazine piece,” he explained. “Matter of fact, it was a story I pitched in a story meeting, not necessarily even for me, though it was based on my experiences…

“Also, a friend had a dog who died tragically, and he ended up in the process spending $17,000 dollars, and I thought ‘Wow, things are really different with dogs than when I was growing up.’

“We had gotten a dog for our family, when my son was 10, and I’ve been noticing—without really thinking about it as a journalist—that people have become obsessed with their dogs in ways that I found really surprising and interesting.”

From www.HomeBookMix.com, an online review of John Homans’s What’s a Dog For?

One of the elements that makes What’s A Dog For? so winning is that it functions partly as a memoir of Homan’s own lifelong dog experiences, particularly involving Stella. Turns out that once he had decided to write a dog book, he’d also almost simultaneously decided to include first-hand dog experiences and observations, weaving in Stella nearly every step of the way.

“The structure of the book was much like the structure of my thinking: it went from my own dog, the dog on my rug, to the farthest corners of philosophy and science. And that’s really how it happened,” he recalls.

“It wasn’t so much that I wanted to write about dogs. It was that I began to contemplate this thing on my rug. She was from Tennessee, and I started to think: ‘Why is she from Tennessee?’ And I learned a lot about the dog rescue movement, over the course of the last four decades, and how they’ve been so successful in places like Long Island, and most of the East Coast and West Coast suburbs.

“And that rescue dogs in New York City that aren’t pit bulls come from elsewhere. They come from, in Stella’s case, Tennessee, or North Carolina or Missouri. I found that surprising and interesting and hadn’t known why that was before I began to explore. So Stella sort of took me into these different worlds.”

Stella and Homans apparently form a curious, intellectually rigorous pair—they’re certainly not willing to roll with a simple, glib explanation for an issue or a shift in the canine landscape when digging deeper (as though seeking to locate a long-ago buried bone) yields a richer, more sophisticated way to frame the matter.

Let’s stay, for instance, with Homans’ comment about rescue dogs in New York City (that aren’t pit bulls or pit bull mixes) coming from elsewhere, an observation spurred by Stella being a Tennessee native. Addressing this in the book, he writes:

It’s a conundrum: rescue dogs are more popular than ever, but on the East Coast, there are far fewer dogs, and especially puppies, that aren’t pit bulls, to rescue. So where do shelter dogs come from? …Dogs in New York, just like people, tend to be from somewhere else. Purebreds can come from anywhere—a breeder upstate, or New Jersey, or Pennsylvania, and often even farther afield. And so can mixed breeds…

Almost as a rule, mutts that aren’t part pit bull are from red states: Virginia, North and South Carolina, Kentucky and Tennessee…Most fundamentally, the dog market is an ongoing transaction between the red states and the blue states, and it’s based on the same basic differences in core values that make our presidential elections so dramatic.

In our radio conversation, I asked Homans to elaborate.

“Well, I think in the blue states, we’re comfortable here in a world with more laws, and more laws telling you what to do,” he responded. “You have to keep your dog on a leash, and you have to spay or neuter your dog, and you can’t shoot your dog [to euthanize it]. And you have to pick up after your dog. Those kinds of prohibitions, in the last four or five decades, are”—here, Homans interrupts himself—“I’ll start at the beginning. Or sort of at the beginning.

“In Levittown, which is the original American suburb, off-leash dogs, loose dogs, were viewed as the second greatest problem, after nuclear annihilation, in the 1950s. And now, you never see a dog that’s off the leash in the suburbs, except behind an invisible fence. Now, on the East Coast, there are no loose dogs to speak of, and all dogs that aren’t pit bulls, are just not breeding.

“Whereas, in the South, say, Tennessee, these kinds of regulations [don’t exist]. You can still shoot your own dog—I mean, I don’t know what the legal situation is—but you’re responsible for your dog there, and you cannot have your dog spayed or neutered. It’s that kind of farmyard ethic. Your dog is your property. And that’s not the way we think of dogs on the East Coast anymore. Therefore that every-man-for-himself, farmer, Jeffersonian ethic still has purchase in the South, and in the West, in ways that it doesn’t on the Coast…

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7yH9nMHkmn4

Mickey Mouse and Pluto in ‘Society Dog Show’ (1939): Mickey enters Pluto in a ritzy dog show. While Mickey grooms Pluto, Pluto starts swooning over Fifi the Peke. Things don’t look good for Mickey and Pluto after the judge who looks over Pluto throws them out when the dog attacks the judge. But when a fire breaks out in the building, Pluto bravely goes in to save Fifi and is a hero.

“Nashville, Tennessee just passed spay-neuter regulations, and they had been euthanizing 70-80% of their dogs, and they thought, finally, that that was an unacceptable situation. That’s Nashville on the path toward what San Francisco has done, which is remarkably successful in terms of its animal control, and New York, which is somewhat less successful, but still successful.”

This sort of thinking, analysis and explanation is wholly in keeping with the modus operandi of What’s A Dog For? Time and time again—often led by the zealous, galloping Stella—Homans probes a canine issue or benchmark, and as the probe unfolds, so much of what’s lurking underneath the surface—the historical or sociological factors affecting it, especially from region to region—is really revealing and intriguing.

“I was especially fascinated by that,” Homans agrees, “and I do think it’s red states. I mean, it’s the don’t-tread-on-me ethic: You can’t tell me what I’m going to do with my dog, or my gun. And that’s not the New York City way—you can tell me what to do with my dog, or my gun.”

The sorts of cultural, systemic differences that Homans is getting at here says far more about how the humans tend to think in this equation than the dogs. But he spends more than a little time delving into how the dogs think, too.

There are a few points in the book where he deals from one angle or another with dogs’ intelligence, and what emerges is a somewhat loftier, more complex perspective than the traditional dogs-are-dopes view.

Sure, he notes that our pooch pals aren’t exactly Mensa members, yet recognizes that those of us who live with dogs are constitutionally reluctant to swing too far in the other direction. “But believing your dog is an imbecile,” Homans writes, “does tend to spoil the party a little bit.”

In our Talking Animals chat, I read him that quote while asking him about the more textured portrait of dog intelligence he paints in the book.

“It’s true,” he says, laughing, “They are imbeciles in certain ways. But on the other hand, one thing I’ve found is they’re quite brilliant and human-like in other ways….Part of what I was exploring was why they’re so suitable—surprisingly suitable—for life in the human world.

“And one of the things I found, one of the things the scientists found, is that even though dogs aren’t anywhere near as smart as humans, or chimpanzees or other primates, they have this quality: they’re ready to be helped. Which is very similar to a kind of human social intelligence.

“One thing that some scientists are amazed by is that dogs can understand the human point. If there are two cups and one has food under it, and you point to it, they’ll go to the cup that has food under it. Oddly, a chimpanzee can’t do that. Because a chimpanzee doesn’t understand that any other creature—chimpanzee or human—would help it. Where the dog can understand that you want to help it, that you want to show him where the food is.”

Throughout the book in all sorts of ways that are never less than engaging, and are often sly and surprising, Homans underscores—and widens—the long-held belief that It’s A Dog’s Life.

It’s striking, for example, to be reminded—or, in some cases, hear for the first time—how many great scholars, great scientists or other great thinkers were important in the dog world. Or were just dog nuts.

I mean, you fully expect in a book like What’s A Dog For? that Pavlov will come up. But, it turns out that Charles Darwin, Sigmund Freud and Jane Goodall—to pick three—forged powerful, often influential relationships with dogs, and their dogs often propelled them into the work they did, even some of the scientific conclusions they drew.

In a chapter titled “Darwin’s Muse,” Homans describes the lifelong, potent canine connection Mr. D. experienced, writing that “In Darwin’s domestic life, from childhood to old age, dogs were a constant, irreplaceable presence.”

Starting with his feeling as a little kid about the family dog, Spark, Darwin was absolutely bonkers about dogs, to the exclusion of nearly anything else. In one of those instances where a parent may have fumbled a perceptive take on their kid’s prospect for the future, Homans reports that Darwin’s father yanked him out of The University of Edinburgh, “scolding him harshly ‘you care for nothing but shooting, dogs, and rat catching, and you will be a disgrace to yourself and your family.’

I’m guessing the level of disgrace diminished upon publication of The Origin Of Species. And on a related note, Homans also points out “The Galapagos finches have gotten most of the attention, but dogs were just as important to Darwin’s scientific enterprise.”

As for Sigmund Freud, Homan writes that the good doctor, “so often chilly about people, could get a little goopy about dogs,” later noting “his dogs became his most trusted companions and even colleagues. He believed in and relied on their insights about people, and they became participants in his practices.” Homans ain’t whistling Dixie: One of Freud’s chows, Yofi, became a fixture at his analytic sessions with patients.

And as a young woman, Jane Goodall, Homans recounts, was torn, weighing the pros and cons of embarking on a trip to Tanzania (she did her pioneering work there, in Gombe) when, “the death of a beloved dog had devastated her, and also allowed her to pull up stakes.”

That dog was Rusty. Homans writes “for Goodall, as for Darwin, the dog was a gateway into nature,” adding that “She wrote in My Life with the Chimpanzees that Rusty was the ‘only dog I’ve ever met who had a sense of justice.’ ”

Later, in the wake of her groundbreaking work in Gombe, when her methods and findings about chimpanzees were being challenged from the academic and scientific establishment, particularly her anthropomorphisms, she didn’t buckle. Homans reports that Goodall—who was a guest on Talking Animals in December of 2009–“wrote ‘I had had a marvelous teacher in animal behavior throughout my childhood. So I ignored the admonitions of Science.’ The teacher was her little dog Rusty.”

And so on.

Perhaps improbably, this material merely scratches the surface of Homans’ book. Elsewhere in the pages, you can find everything from information about the very first dog, to the human biochemical impact of hanging with dogs (the hormone oxytocin spikes), to dog training—include the pro- and anti-Cesar “The Dog Whisperer” Millan factions—to the Canine Science Forum at the University of Vienna, to dogs as descendants of wolves, to dog shows (and all the attendant concerns about inbreeding and overbreeding), to the highly polarizing realm of no-kill shelters, to breeding dogs so as circumvent human allergy problems, among many, many other topics.

In large part, these constitute the answers to some of the Stella-triggered questions the author set out to answer, a journey that raised new questions as initial ones were answered, further expanding the scope of the trek—to the reader’s great benefit.

As Homans mentioned at one point in our radio discussion, an initial query was “Why is this predatory, wolf-ish creature that’s laying on my rug my friend? And by the end of the book, I sort of understood it better.”

Same here, John, same here. And so much more.

Famous (or infamous) dog lovers cavort with their canines: Adolf Hitler, Eva Braun and Sigmund Freud to the tune of Cliff ‘Ukelele Ike’ Edwards’ ‘My Dog Loves Your Dog.’ If Edwards’s voices sounds familiar, the answer is yes, he was the voice of Jiminy Cricket in Disney’s Pinochio. His 1940 recording of ‘When You Wish Upon a Star’ is in the Grammy Hall of Fame. Take that, Beyonce.

Click here to listen to the complete interview with John Homans on Talking Animas

Click here to listen to Jane Goodall’s interview on Talking Animals